Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Plant Sciences

Photorespiration (PR) is a metabolic repair pathway that acts in oxygenic photosynthetic organisms to degrade a toxic product of oxygen fixation generated by the enzyme ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Within the metabolic pathway, energy is consumed and carbon dioxide released.

- photorespiration

- photosynthesis

- transport protein

- plant

- Rubisco

- metabolite

- synthetic bypass

- C4 photosynthesis

1. Introduction—The Photorespiratory Metabolism

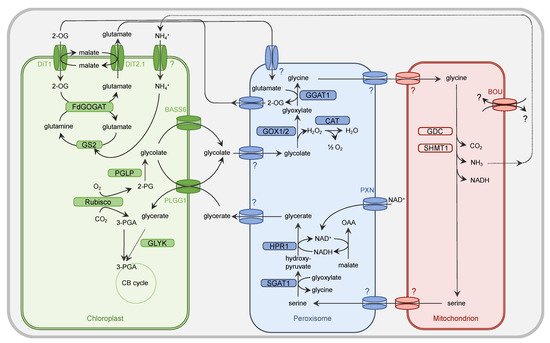

Oxygenic photosynthesis builds the foundation of life on earth. By the action of the photosynthesis apparatus, energy from the sun is harvested and converted into chemical energy, with oxygen (O2) as a byproduct. The chemical energy drives the Calvin–Benson cycle to fix atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) and produce sugars. Central to CO2 fixation is the enzyme ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco). This world’s most abundant protein accomplishes assimilation of ca. 250 billion tons of CO2 into biomass per year [1]. As a biochemical reaction, Rubisco catalyzes the condensation of one molecule of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate with one molecule of CO2 to produce two molecules of 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PGA). However, the enzyme also accepts O2 as a substrate. In the case of oxygenation activity, Rubisco forms one molecule of 3-PGA and one molecule of 2-phosphoglycolate (2-PG) [2]. 2-PG acts as an inhibitor of enzymes of the central carbon metabolism. These are phosphofructokinase [3], sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphatase [4], and triose phosphate isomerase [5]. Confronted with the challenge to perform oxygenic photosynthesis and to thrive, cyanobacteria have evolved the photorespiratory (PR) metabolism to degrade 2-PG rapidly [6][7]. Oxygenic photosynthetic eukaryotes, including algae and land plants, inherited the indispensable ability to perform PR metabolism (reviewed in [8]). The vital necessity of PR is indicated by the typical PR phenotype: mutants with defects in PR metabolism grow only in an atmosphere with elevated CO2 concentrations. When cultivated under ambient CO2 conditions (currently 0.041% CO2 in air) growth is impaired or even fully inhibited (reviewed in [9]). By the concerted action of nine enzymatic steps (Figure 1), the metabolic repair pathway leads to the detoxification of 2-PG and recycles 75% of the carbon contained in 2-PG to regenerate 3-PGA, which is resupplied to the Calvin–Benson (CB) cycle for the regeneration of the acceptor molecule ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate and production of triose phosphates. The remaining 25% are lost in the form of CO2 during the glycine decarboxylation reaction (reviewed in [8][10]). Reduction in photosynthetic efficiency and yield is estimated to reach about 20% of the CO2 previously fixed by photosynthesis in C3 plants under temperate climate conditions and can be even higher under hot and dry conditions [10]. Consequently, PR—“respiration in light”—is considered as a wasteful process. However, besides the detoxification of 2-PG, there are additional beneficial traits of the pathway: Firstly, since PR metabolism dissipates energy and reducing power its action lowers the potential of photoinhibition [11]. Secondly, PR metabolism is not an isolated pathway but is highly metabolically interconnected (reviewed in [12][13][14]). Besides the carbon recycling, it is also intertwined with nitrogen [15] and sulphur metabolism [16], and serves the production of amino acids (glycine, serine, glutamate, cysteine) and activated one-carbon units [10][17].

Figure 1. Simplified presentation of the plant PR metabolism. Oxygenation activity of Rubisco within the chloroplast results in the generation of one molecule of 3-PGA and 2-PG each. While 3-PGA is metabolized in the CB cycle, 2-PG is degraded by the PR metabolism. Within the chloroplast, 2-PG is dephosphorylated by 2-PG phosphatase (PGLP). Formed glycolate is exported from the chloroplast by PLGG1 and BASS6 and enters the peroxisome by a yet unidentified (?) translocator. Glycolate oxidase (GOX1/2) generates glyoxylate and H2O2. The latter one is converted by catalase (CAT) activity into O2 and H2O. The PR intermediate glyoxylate is aminated by glutamate:glyoxylate aminotransferase (GGAT1) to yield glycine. Glutamate serves as a donor for the amino group. The peroxisomal importer for this amino acid but also glycine is to date unknown. Glycine needs to be imported by an unknown translocator into the mitochondrion. Here, the concerted action of the multienzyme system glycine decarboxylase (GDC) and serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT) results in release of CO2 and NH3 from one molecule of glycine but also conversion of another molecule of glycine into serine. The substrate(s) of the transporter À BOU DE SOUFFLE (BOU) are unclear. BOU is likely involved in mitochondrial glutamate transport and functionally linked with glycine-to-serine conversion. Export of serine from the mitochondrion is facilitated by an unknown transporter protein. This applies also to the import into the peroxisome. Serine is deaminated by serine:glyoxylate aminotransferase (SGAT1) to form hydroxypyruvate. For the subsequent reduction of this intermediate to glycerate, hydroxypyruvate reductase 1 (HPR1) depends on NADH, which is provided by the oxidation of OAA into malate. NAD+ is basically imported into peroxisome by the peroxisomal NAD carrier PXN. Glycerate leaves the peroxisome by an unknown mechanism and imported into the chloroplast by PLGG1. The concluding step in the PR pathway is the phosphorylation of glycerate and formation of 3-PGA by glycerate kinase (GLYK). 3-PGA enters the CB cycle. The dicarboxylate translocators DiT1 and Dit2.1 function as two-translocator system for the refixation of NH4+ in the chloroplast by the GS/FdGOGAT system. Further details are given in the main body.

2. Metabolite Channeling in Photorespiratory Metabolism

In plants, the PR pathway is distributed over the three organelles chloroplast, peroxisome, and mitochondrion (Figure 1). The organellar compartmentalization allows embedding of the PR pathway into the signature metabolic alleys of the specific organelle. To enable efficient flux of metabolites through the pathway and also supply with co-factors for involved enzymes, specific transport steps are inevitable. In the following, the current knowledge about those transport processes at the plastidial, peroxisomal, and mitochondrial membranes is presented. A list of identified transport proteins involved in PR in Arabidopsis thaliana (henceforth Arabidopsis) is given in Table 1.

Table 1. List of identified PR transporters in Arabidopsis thaliana.

| Transporter | Abbreviation | Substrate | Arabidopsis thaliana Identifier | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| plastidial glycolate/glycerate transporter | PLGG1 | glycerate/glycolate | At1g32080 | [18] |

| bile acid sodium symporter 6 | BASS6 | glycolate | At4g22840 | [19] |

| 2-OG/malate translocator | DiT1/OMT1 | 2-OG/malate | At5g12860 | [20][21] |

| glutamate/malate translocator | DiT2.1/DCT1 | glutamate/malate | At5g64290 | |

| À BOUT DE SOUFFLE | BOU | glutamate | At5g46800 | [22][23] |

| uncoupling protein 1 | UCP1 | aspartate/glutamate | At3g54110 | [24][25] |

2.1. Transport Processes at Chloroplasts

Chloroplasts, the starting and end point of the PR pathway, are surrounded by two membranes, namely the outer and the inner envelope. The outer envelope contains porins, which make it permeable to low molecular weight molecules. In contrast, the inner envelope forms a permeability barrier for metabolites and ions. As such, the shuttle across the inner envelope requires specific transport proteins [26][27]. Early studies on isolated chloroplasts from spinach and pea leaves showed that the core substrates of the PR pathway, glycerate and glycolate, are both shuttled across the chloroplast inner envelope in a carrier-mediated process. It was initially proposed that the metabolite shuttle was mediated by the same carrier protein in an anion-exchange reaction. Subsequent experiments also suggested a proton-driven symport as transport mode for glycolate [28][29][30][31][32]. It took about 40 years until the respective genes encoding for those transporters were identified and characterized on a molecular level in Arabidopsis [18][19]. In 2013, the plastidial glycolate/glycerate transporter PLGG1 was discovered by co-expression analysis. Knockout mutants deficient for PLGG1 show a typical PR phenotype and accumulate intermediates of the PR pathway, such as glycolate, glycine, and glycerate. Biochemical studies with recombinant PLGG1 protein as well as O2 flux analyses of wildtype and plgg1 knockout plants eventually revealed its role in PR as a plastidial glycolate/glycerate translocator [18]. Four years later, yeast complementation assays as well as phenotypic analyses of a knockout mutant identified the bile acid sodium symporter 6 (BASS6) as a plastidial glycolate transporter in Arabidopsis [19]. To identify a transporter involved in PR, South and colleagues exploited that PR mutants are impaired in photosystem II activity and thus display reduced Fv/Fm chlorophyll fluorescence in low CO2 conditions [19][33]. Similar to the plgg1 mutant, the bass6 mutant accumulates photorespiratory intermediates, such as glycolate and glycine but not glycerate, indicating its role as glycolate but not glycerate transporter. A double-knockout mutant of both plgg1 and bass6 contains significantly higher amounts of glycolate than either of the single-mutant lines or the wildtype. Interestingly, accumulation of serine and glycine reverts back to wildtype levels, indicating an overall alteration of PR metabolism [19]. Together, PLGG1 and BASS6 allow balanced export of two molecules of glycolate against one molecule of glycerate [18][19].

The first Arabidopsis PR transporter to be identified was a chloroplast dicarboxylate carrier in the early 1980s. The dct mutant was identified in a forward genetic approach developed by Chris and Shauna Sommerville in William Ogren’s laboratory. The mutant is lacking a transporter of the inner envelope, which is capable of catalyzing the flux of aspartate, 2-oxoglutarate (2-OG), malate, and glutamate [34][35]. Soon after, it was demonstrated that the transport of dicarboxylates across the chloroplast inner envelope requires at least two distinct carriers, later termed as 2-OG/malate translocator (DiT1/OMT) and glutamate/malate translocator (DiT2.1/DCT1) [36][37]. Both proteins exhibit overlapping substrate specificities. While both DiT1/OMT and DiT2.1/DCT1 are specific for dicarboxylates, such as malate, 2-OG, fumarate, and succinate, DiT2.1/DCT1 also accepts the amino acids glutamate and aspartate. Comprehensive genetic and biochemical studies supported the initial model of a two-translocator system for the refixation of ammonia in the chloroplast by the glutamine synthetase (GS)/ferredoxin-dependent glutamine:oxoglutarate (FdGOGAT) system. DiT1/OMT imports 2-OG into plastids in counter exchange with malate export. DiT2.1/DCT1 exports glutamate against cytosolic malate import, resulting in zero net-malate transport [20][21][38][39][40]. During PR, ammonia is released by the glycine decarboxylase (GDC) multi enzyme system in the mitochondria, and refixed by the GS/FdGOGAT system in the chloroplasts. As reviewed before, ammonium import into chloroplasts likely requires active transport or channeling [12]. However, such a transporter has not been identified to date. Thus, it remains elusive how and in which form ammonium crosses the plastid inner envelope.

2.2. Transport Processes at Peroxisomes

In the early 1970s, Tolbert’s laboratory at the Michigan State University discovered that peroxisomes in photosynthetic plant tissues play an essential role in PR. Tolbert and his colleagues intensively studied the peroxisomal enzymes involved in the fate of glycolate by labelling experiments, which is known as the glycolate or Tolbert pathway [41][42]. To functionally integrate leaf peroxisomes within the PR metabolism, a high flux of core intermediates across the peroxisomal membrane has to be coordinated [13]. For example, glycolate and serine have to enter peroxisomes, whereas glycerate and glycine have to be exported (Figure 1) for further conversion [14].

Beyond the transfer of core metabolites, PR-associated reactions within peroxisomes require the shuttling of additional molecules [14]. The reduction of hydroxypyruvate to glycerate by peroxisomal HPR1 depends on NADH, which is provided via the malate/oxaloacetate (OAA) shuttle [43]. This redox shuttle comprises two transport steps: the import of malate and the export of OAA. For the transamination of glyoxylate to glycine by glutamate:glyoxylate aminotransferase (GGAT), the amino group donor glutamate has to be transferred from chloroplasts to peroxisomes, where in return its 2-keto acid 2-OG has to be shuttled back into plastids to close the PR nitrogen cycle (Figure 1).

The uptake of tightly bound cofactors into peroxisomes for the PR enzymes, such as flavin mononucleotide (FMN)-containing GOX [44] or pyridoxal phosphate (PLP)-dependent aminotransferase [45][46], can be neglected. In contrast to chloroplasts and mitochondria, the peroxisomal matrix proteins can fold, acquire cofactors, and assemble into oligomers in the cytosol before targeting to peroxisomes [47]. Only for the coenzyme NAD+ [48] does a specific import mechanism exist at the peroxisomal membrane in plants (Figure 1).

Since the lipid bilayer functions as a main permeability barrier, most solutes cannot freely pass the peroxisomal membrane [13][49]. Channeling PR metabolites into and out of peroxisomes is achieved by integral membrane proteins that mediate the passage of a variety of PR intermediates. The recent model for peroxisomes suggests that the peroxisomal membrane contains two types of transporters: non-selective pore-forming diffusion channels and highly specific carrier proteins (for review, see [13][49]). Porins allow the transport of small hydrophilic solutes with molecular masses up to 300–400 Da, such as carboxylic acids and amino acids, whereas carrier-type transporters are involved for the transfer of larger molecules, such as NAD+ [13][49]. However, our current knowledge about the molecular identity of these transport proteins responsible for shuttling PR intermediates across the peroxisome membrane is rather limited.

First studies investigating the traffic of PR metabolites at the peroxisomal membrane were performed with leaf peroxisomes from spinach. The peroxisomal PR cycle was stimulated in vitro by adding glycolate, serine, glutamate, and malate to these intact organelles and analyzed by detecting the formation of glycerate [50][51][52]. These experiments indicated the existence of efficient uptake systems for these molecules across the peroxisomal membrane, allowing functional PR metabolism in isolated spinach peroxisomes.

Further electrophysiological lipid bilayer measurements using enriched peroxisomal membranes characterized a porin-like channel in spinach leaf peroxisomes [53][54]. This high-abundant channel is strongly selective for negatively charged solutes and displays a broad permeability for structurally diverse inorganic and organic anions. In respect to peroxisomal PR metabolism, this specific porin facilitates the transport of the anionic intermediates glycolate, glycerate, glutamate, malate, OAA, and 2-OG, but does not allow the passage of the zwitter-ionic amino acids glycine and serine (for review see [55]). Such a peroxisomal channel represents an efficient transport system allowing high flux of most of the metabolic intermediates through the PR cycle (Figure 1).

In Arabidopsis, the peroxisomal membrane protein of 22 kDa (PMP22) is proposed to be responsible for the pore-like channel activities, which has been described above [56]. This protein belongs to a small eukaryotic family of non-selective pore-forming channels, which are distributed to mitochondria and peroxisomes in human, mouse, yeast, and plants [13]. However, if the Arabidopsis PMP22 contributes to the permeability of PR, intermediates for the peroxisomal metabolism needs to be investigated in the future.

It is still an open question how the amino acids glycine and serine are shuttled through the peroxisomal membrane during PR. In plants, a high number of amino acid transporter classified into three major families are known. While numerous plasma membrane-localized amino acid carriers have been reported, only a few members have been found in plastids and mitochondria, but no member of this carrier group has been identified in peroxisomes so far [57].

To provide the peroxisomal malate dehydrogenase as part of the redox shuttle with NAD, Arabidopsis possesses a peroxisomal NAD carrier, called PXN [48][58]. This carrier protein imports NAD+ into peroxisomes to allow redox reactions in the peroxisomal lumen (Figure 1). In case of PR, NAD+ is reduced to NADH via the oxidation of malate to OAA, providing NADH for the HPR1 reaction. The Arabidopsis loss-of-function mutants for PXN do not display any obvious growth defects under PR conditions. Instead, dynamic light conditions, such as high-light fluctuations, triggered a significant photosynthetic defect in the pxn plants, whereas elevated CO2 levels completely rescued the observed phenotype [59]. It is assumed that the loss of PXN leads to an impairment of photosynthesis, because the PR pathway is disturbed due to an imbalance of reducing equivalents. Peroxisomal NAD+ imported by PXN might compensate for an increased NADH demand of the HPR1 reaction during PR under abiotic stress conditions [59].

2.3. Transport Processes at Mitochondria

Similar to plastids, mitochondria are surrounded by two membranes, namely the outer and inner mitochondrial membrane. The first of these two membranes is permeable to molecules smaller than 5 kDa [60]. In contrast, metabolites rely on specific translocators in order to cross the inner mitochondrial membrane. Arabidopsis mitochondria contain at least 128 different transport proteins, many of which belong to the mitochondrial carrier family [61]. To date, none of them could be assigned to function either as glycine or as serine transporters. Earlier studies on isolated mitochondria from pea leaves suggested that the uptake of both core metabolites of the PR pathway, glycine and serine, is likely mediated by non-specific diffusion [62][63]. In contrast, a similar study on isolated mitochondria from spinach leaves proposed a concentration-dependent transport system. Glycine and serine are actively transported across the inner mitochondrial membrane at concentrations lower than 0.5 mM, whereas the diffusion process dominates at concentrations higher than 0.5 mM [64]. However, it remains elusive to date how glycine and serine cross the mitochondrial inner membrane and, if present, which transport proteins catalyze the putative shuttle of one or both metabolites.

During the combined reaction of GDC and serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT) in the mitochondria, one molecule of serine is formed out of two molecules of glycine. Additionally, ammonia, NADH, and CO2 are released in equimolar amounts. It is assumed that ammonia diffuses towards the chloroplast where it is reassimilated by the GS/FdGOGAT system. However, given the toxicity of free ammonia, it was speculated that ammonia is transported towards the plastids in the form of an amino acid, such as glutamine or citrulline, utilizing an ornithine–citrulline or glutamate–glutamine shuttle system [65]. Both scenarios require the presence of a GS in mitochondria [65]. GS was previously hypothesized to be dual-localized to chloroplasts and mitochondria based on localization studies using fluorescent fusion-proteins [66]. However, in a recent proteomic study, it was reported that GS exists only in 26 copies per mitochondrion [67], which does not meet the demand for the high fluxes during PR, and is therefore negligible. In addition to a putative mitochondrial ammonia transporter, transporters of GDC and SHMT cofactors or their precursors remain to be identified. There are at least five transport steps necessary to provide GDC and SHMT with their respective cofactors (Vitamin B6 vitamers, lipoate or octanoate, malonate, folate precursor 6-hydroxymethyldihydropterine, NAD+). They were previously reviewed by Eisenhut and coworkers [68].

Recent advances have been made by identifying transporters of auxiliary metabolic pathways, such as the uncoupling proteins UCP1 and UCP2 in Arabidopsis [24][25]. UCP1 and UCP2 have a broad substrate spectrum. Next to the amino acids glutamate and aspartate, they also accept the dicarboxylates malate, succinate, and malonate to a lesser extent [25]. A recent study proposed that UCP1 and UCP2 contribute to the shuttle of redox equivalents during PR by catalyzing an electroneutral aspartate/glutamate exchange [25]. Aspartate and glutamate are substrate and product of the mitochondrial glutamate:OAA transaminase, which produces OAA that is required for NAD+-recycling by mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase. Analyses of Arabidopsis ucp1 knockout mutants support this hypothesis. Even though ucp1 mutants do not show a typical photorespiratory phenotype, they exhibit reduced levels of malate, reduced CO2 assimilation rates, and a strong reduction in glycine oxidation rate [24][25]. Double-knockout mutants of both UCP1 and UCP2 do not show any synergistic effect. Given the fact that UCP2 has been alternatively reported to reside in the membrane of the Golgi apparatus [69], its involvement in PR is still under debate [70][71]. In addition to UCP1, redox equivalents might be shuttled in the form of OAA/malate. The Arabidopsis genome contains three dicarboxylate carriers (DIC1-3), which are capable of efficiently transporting different dicarboxylates, such as malate, oxalate, malonate, succinate, and OAA [72]. However, their physiological role remains elusive as to date mutant studies are not available.

In 2013, the mitochondrial carrier protein À BOUT DE SOUFFLE (BOU) was identified in a co-expression analysis with PR genes in Arabidopsis [22]. Knockout mutants in BOU show a strong PR phenotype and accumulate intermediates of the PR pathway. The study proposed a transport function of BOU linked with the activity of GDC and SHMT. The transport substrate, however, remained enigmatic [22]. Recently, it was demonstrated that BOU facilitates mitochondrial glutamate transport in yeast [23]. Glutamate is essential for polyglutamylation of tetrahydrofolate (derivate of Vitamin B9), a cofactor of the T-protein of GDC and the SHMT. However, polyglutamylating enzymes are present in the chloroplasts and the cytosol as well, and it remains to be clarified how and which form of Vitamin B9 is transported across the mitochondrial membrane [73]. In a recent review, it was suggested that BOU might play a role in mitochondrial protein synthesis by supplying the mitochondria with glutamate [71]. Alternatively, glutamate might not be the only substrate of BOU. Besides glutamate, Porcelli and coworkers tested many additional substrates, such as aminoadipate, aspartate, asparagine, and glutamine. Transport activity could only be detected for L-homocysteine sulfinic acid, a substrate analog of glutamate [23]. However, the study lacks molecules that are related to PR, such as glycine, serine, and cofactors of the GDC/SHMT reaction. Further studies will be necessary to identify the physiological role of BOU with respect to PR.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/plants10050880

References

- Bracher, A.; Whitney, S.M.; Hartl, F.U.; Hayer-Hartl, M. Biogenesis and Metabolic Maintenance of Rubisco. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017, 68, 29–60.

- Bowes, G.; Ogren, W.L.; Hageman, R.H. Phosphoglycolate production catalyzed by ribulose diphosphate carboxylase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1971, 45, 716–722.

- Kelly, G.J.; Latzko, E. Inhibition of spinach-leaf phosphofructokinase by 2-phosphoglycollate. FEBS Lett. 1976, 68, 55–58.

- Flügel, F.; Timm, S.; Arrivault, S.; Florian, A.; Stitt, M.; Fernie, A.R.; Bauwe, H. The photorespiratory metabolite 2-phosphoglycolate regulates photosynthesis and starch accumulation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 2537–2551.

- Anderson, L.E. Chloroplast and Cytoplasmic enzymes. II Pea leaf triose Phosphate Isomerases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1971, 22, 237–244.

- Eisenhut, M.; Ruth, W.; Haimovich, M.; Bauwe, H.; Kaplan, A.; Hagemann, M. The photorespiratory glycolate metabolism is essential for cyanobacteria and might have been conveyed endosymbiontically to plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17199–17204.

- Hagemann, M.; Fernie, A.R.; Espie, G.S.; Kern, R.; Eisenhut, M.; Reumann, S.; Bauwe, H.; Weber, A.P.M. Evolution of the biochemistry of the photorespiratory C2 cycle. Plant Biol. 2013, 15, 639–647.

- Hagemann, M.; Bauwe, H. Photorespiration and the potential to improve photosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2016, 35, 109–116.

- Timm, S.; Bauwe, H. The variety of photorespiratory phenotypes - employing the current status for future research directions on photorespiration. Plant Biol. 2013, 15, 737–747.

- Bauwe, H.; Hagemann, M.; Fernie, A.R. Photorespiration: Players, partners and origin. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 330–336.

- Kozaki, A.; Takeba, G. Photorespiration protects C3 plants from photooxidation. Nature 1996, 384, 557–560.

- Eisenhut, M.; Hocken, N.; Weber, A.P.M. Plastidial metabolite transporters integrate photorespiration with carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur metabolism. Cell Calcium 2015, 58, 98–104.

- Charton, L.; Plett, A.; Linka, N. Plant peroxisomal solute transporter proteins. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2019, 61, 817–835.

- Eisenhut, M.; Roell, M.S.; Weber, A.P.M. Mechanistic understanding of photorespiration paves the way to a new green revolution. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1762–1769.

- Bloom, A.J. Photorespiration and nitrate assimilation: A major intersection between plant carbon and nitrogen. Photosynth. Res. 2015, 123, 117–128.

- Samuilov, S.; Brilhaus, D.; Rademacher, N.; Flachbart, S.; Arab, L.; Alfarraj, S.; Kuhnert, F.; Kopriva, S.; Weber, A.P.M.; Mettler-Altmann, T.; et al. The photorespiratory BOU gene mutation alters sulfur assimilation and its crosstalk with carbon and nitrogen metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 871, 1–21.

- Hodges, M.; Dellero, Y.; Keech, O.; Betti, M.; Raghavendra, A.S.; Sage, R.; Zhu, X.G.; Allen, D.K.; Weber, A.P.M. Perspectives for a better understanding of the metabolic integration of photorespiration within a complex plant primary metabolism network. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 3015–3026.

- Pick, T.R.; Bräutigam, A.; Schulz, M.A.; Obata, T.; Fernie, A.R.; Weber, A.P.M. PLGG1, a plastidic glycolate glycerate transporter, is required for photorespiration and defines a unique class of metabolite transporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 3185–3190.

- South, P.F.; Walker, B.J.; Cavanagh, A.P.; Rolland, V.; Badger, M.; Ort, D.R. Bile Acid Sodium Symporter BASS6 Can Transport Glycolate and Is Involved in Photorespiratory Metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 808–823.

- Taniguchi, M.; Taniguchi, Y.; Kawasaki, M.; Takeda, S.; Kato, T.; Tabata, S.; Miyake, H.; Sugiyama, T. Identifying and Characterizing Plastidic 2-Oxoglutarate/Malate and Dicarboxylate Transporters in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002, 43, 706–717.

- Renné, P.; Dreßen, U.; Hebbeker, U.; Hille, D.; Flügge, U.I.; Westhoff, P.; Weber, A.P.M. The Arabidopsis mutant dct is deficient in the plastidic glutamate/malate translocator DiT2. Plant J. 2003, 35, 316–331.

- Eisenhut, M.; Planchais, S.; Cabassa, C.; Guivarc’H, A.; Justin, A.M.; Taconnat, L.; Renou, J.P.; Linka, M.; Gagneul, D.; Timm, S.; et al. Arabidopsis A BOUT de SOUFFLE is a putative mitochondrial transporter involved in photorespiratory metabolism and is required for meristem growth at ambient CO2 levels. Plant J. 2013, 73, 836–849.

- Porcelli, V.; Vozza, A.; Calcagnile, V.; Gorgoglione, R.; Arrigoni, R.; Fontanesi, F.; Marobbio, C.M.T.; Castegna, A.; Palmieri, F.; Palmieri, L. Molecular identification and functional characterization of a novel glutamate transporter in yeast and plant mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenergy 2018, 1859, 1249–1258.

- Sweetlove, L.J.; Lytovchenko, A.; Morgan, M.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Taylor, N.L.; Baxter, C.J.; Eickmeier, I.; Fernie, A.R. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein is required for efficient photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 19587–19592.

- Monné, M.; Daddabbo, L.; Gagneul, D.; Obata, T.; Hielscher, B.; Palmieri, L.; Miniero, D.V.; Fernie, A.R.; Weber, A.P.M.; Palmieri, F. Uncoupling proteins 1 and 2 (UCP1 and UCP2) from Arabidopsis thaliana are mitochondrial transporters of aspartate, glutamate, and dicarboxylates. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 4213–4227.

- Heldt, H.W.; Rapley, L. Unspecific permeation and specific uptake of substances in spinach chloroplasts. FEBS Lett. 1970, 7, 139–142.

- Heldt, H.W.; Sauer, F. The inner membrane of the chloroplast envelope as the site of specific metabolite transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenergy 1971, 234, 83–91.

- Bassham, J.A.; Kirk, M.; Jensen, R.G. Photosynthesis by isolated chloroplasts I. Diffusion of labeled photosynthetic intermediates between isolated chloroplasts and suspending medium. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenergy 1968, 153, 211–218.

- Heber, U.; Kirk, M.R.; Gimmler, H.; Schäfer, G. Uptake and reduction of glycerate by isolated chloroplasts. Planta 1974, 120, 31–46.

- Robinson, S.P. Transport of Glycerate across the Envelope Membrane of Isolated Spinach Chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 1982, 70, 1032–1038.

- Howitz, K.T.; McCarty, R.E. Evidence for a glycolate transporter in the envelope of pea chloroplasts. FEBS Lett. 1983, 154, 339–342.

- Howitz, K.T.; McCarty, R.E. Kinetic characteristics of the chloroplast envelope glycolate transporter. Biochemistry 1985, 24, 2645–2652.

- Takahashi, S.; Bauwe, H.; Badger, M. Impairment of the Photorespiratory Pathway Accelerates Photoinhibition of Photosystem II by Suppression of Repair But Not Acceleration of Damage Processes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 487–494.

- Somerville, S.C.; Ogren, W.L. An Arabidopsis thaliana mutant defective in chloroplast dicarboxylate transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1983, 80, 1290–1294.

- Somerville, S.C.; Somerville, C.R. A mutant of Arabidopsis deficient in chloroplast dicarboxylate transport is missing an envelope protein. Plant Sci. Lett. 1985, 37, 217–220.

- Woo, K.C.; Flügge, U.I.; Heldt, H.W. A Two-Translocator Model for the Transport of 2-Oxoglutarate and Glutamate in Chloroplasts during Ammonia Assimilation in the Light. Plant Physiol. 1987, 84, 624–632.

- Flügge, I.U.; Woo, K.C.C.; Heldt, H.C.W. Characteristics of 2-oxoglutarate and glutamate transport in spinach chloroplasts. Planta 1988, 174, 534–541.

- Weber, A.; Menzlaff, E.; Arbinger, B.; Gutensohn, M.; Eckerskorn, C.; Fluegge, U.-I. The 2-oxoglutarate/malate translocator of chloroplast envelope membranes: Molecular cloning of a transporter containing a 12-helix motif and expression of the functional protein in yeast cells. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 2621–2627.

- Weber, A.; Flügge, U. Interaction of cytosolic and plastidic nitrogen metabolism in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 865–874.

- Schneidereit, J.; Häusler, R.; Fiene, G.; Kaiser, W.; Weber, A. Antisense repression reveals a crucial role of the plastidic 2-oxoglutarate/malate translocator DiT1 at the interface between carbon and nitrogen metabolism. Plant J. 2006, 45, 206–224.

- Tolbert, N.E.; Yamazaki, R.K. Leaf Peroxisomes and their Relation to Photorespiration and Photosynthesis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1969, 168, 325–341.

- Yamazaki, R.K.; Tolbert, N.E. Enzymic characterization of leaf peroxisomes. J. Biol. Chem. 1970, 245, 5137–5144.

- Liang, Z.; Yu, C.; Huang, A.H.C. Conversion of glycerate to serine in intact spinach leaf peroxisomes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1984, 233, 393–401.

- Esser, C.; Kuhn, A.; Groth, G.; Lercher, M.J.; Maurino, V.G. Plant and animal glycolate oxidases have a common eukaryotic ancestor and convergently duplicated to evolve long-chain 2-hydroxy acid oxidases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31, 1089–1101.

- Liepman, A.H.; Olsen, L.J. Peroxisomal alanine: Glyoxylate aminotransferase (AGT1) is a photorespiratory enzyme with multiple substrates in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2001, 25, 487–498.

- Igarashi, D.; Miwa, T.; Seki, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Kato, T.; Tabata, S.; Shinozaki, K.; Ohsumi, C. Identification of photorespiratory glutamate:glyoxylate aminotransferase (GGAT) gene in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003, 33, 975–987.

- Léon, S.; Goodman, J.M.; Subramani, S. Uniqueness of the mechanism of protein import into the peroxisome matrix: Transport of folded, co-factor-bound and oligomeric proteins by shuttling receptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2006, 1763, 1552–1564.

- Bernhardt, K.; Wilkinson, S.; Weber, A.P.M.; Linka, N. A peroxisomal carrier delivers NAD+ and contributes to optimal fatty acid degradation during storage oil mobilization. Plant J. 2012, 69, 1–13.

- Linka, N.; Theodoulou, F.L. Metabolite transporters of the plant peroxisomal membrane: Known and unknown. Subcell. Biochem. 2013, 69, 169–194.

- Kisaki, T.; Tolbert, N.E. Glycolate and Glyoxylate Metabolism by Isolated Peroxisomes or Chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 1969, 44, 242–250.

- Chang, C.-C.; Huang, A.H.C. Metabolism of Glycolate in Isolated Spinach Leaf Peroxisomes: Kinetics of Glyoxylate, Oxalate, Carbon Dioxide, and Glycine Formation. Plant Physiol. 1981, 67, 1003–1006.

- Heupel, R.; Markgraf, T.; Robinson, D.G.; Heldt, H.W. Compartmentation Studies on Spinach Leaf Peroxisomes. Plant Physiol. 1991, 96, 971–979.

- Reumann, S.; Maier, E.; Benz, R.; Heldt, H.W. The membrane of leaf peroxisomes contains a porin-like channel. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 17559–17565.

- Reumann, S.; Maier, E.; Heldt, H.W.; Benz, R. Permeability properties of the porin of spinach leaf peroxisomes. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998, 251, 359–366.

- Reumann, S. The structural properties of plant peroxisomes and their metabolic significance. Biol. Chem. 2000, 381, 639–648.

- Reumann, S.; Weber, A.P.M. Plant peroxisomes respire in the light: Some gaps of the photorespiratory C2 cycle have become filled—Others remain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2006, 1763, 1496–1510.

- Yang, G.; Wei, Q.; Huang, H.; Xia, J. Amino Acid Transporters in Plant Cells: A Brief Review. Plants 2020, 9, 967.

- Agrimi, G.; Russo, A.; Pierri, C.L.; Palmieri, F. The peroxisomal NAD+ carrier of Arabidopsis thaliana transports coenzyme A and its derivatives. J. Bioenergy Biomembr. 2012, 44, 333–340.

- Li, J.; Tietz, S.; Cruz, J.A.; Strand, D.D.; Xu, Y.; Chen, J.; Kramer, D.M.; Hu, J. Photometric screens identified Arabidopsis peroxisome proteins that impact photosynthesis under dynamic light conditions. Plant J. 2019, 97, 460–474.

- Zalman, L.S.; Nikaido, H.; Kagawa, Y. Mitochondrial outer membrane contains a protein producing nonspecific diffusion channels. J. Biol. Chem. 1980, 255, 1771–1774.

- Møller, I.M.; Rao, R.S.P.; Jiang, Y.; Thelen, J.J.; Xu, D. Proteomic and Bioinformatic Profiling of Transporters in Higher Plant Mitochondria. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1190.

- Day, D.A.; Wiskich, J.T. Glycine transport by pea leaf mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1980, 112, 191–194.

- Proudlove, M.O.; Moore, A.L. Movement of amino acids into isolated plant mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1982, 147, 26–30.

- Yu, C.; Claybrook, D.L.; Huang, A.H.C. Transport of glycine, serine, and proline into spinach leaf mitochondria. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1983, 227, 180–187.

- Linka, M.; Weber, A.P.M. Shuffling ammonia between mitochondria and plastids during photorespiration. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 461–465.

- Taira, M.; Valtersson, U.; Burkhardt, B.; Ludwig, R.A. Arabidopsis thaliana GLN2-Encoded Glutamine Synthetase Is Dual Targeted to Leaf Mitochondria and Chloroplasts. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2048–2058.

- Fuchs, P.; Rugen, N.; Carrie, C.; Elsässer, M.; Finkemeier, I.; Giese, J.; Hildebrandt, T.M.; Kühn, K.; Maurino, V.G.; Ruberti, C.; et al. Single organelle function and organization as estimated from Arabidopsis mitochondrial proteomics. Plant J. 2020, 101, 420–441.

- Eisenhut, M.; Pick, T.R.; Bordych, C.; Weber, A.P.M. Towards closing the remaining gaps in photorespiration—The essential but unexplored role of transport proteins. Plant Biol. 2013, 15, 676–685.

- Parsons, H.T.; Christiansen, K.; Knierim, B.; Carroll, A.; Ito, J.; Batth, T.S.; Smith-Moritz, A.M.; Morrison, S.; McInerney, P.; Hadi, M.Z.; et al. Isolation and Proteomic Characterization of the Arabidopsis Golgi Defines Functional and Novel Components Involved in Plant Cell Wall Biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2012, 159, 12–26.

- Fernie, A.R.; Cavalcanti, J.H.F.; Nunes-Nesi, A. Metabolic Roles of Plant Mitochondrial Carriers. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1013.

- Nunes-Nesi, A.; Cavalcanti, J.H.F.; Fernie, A.R. Characterization of In Vivo Function(s) of Members of the Plant Mitochondrial Carrier Family. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1226.

- Palmieri, L.; Picault, N.; Arrigoni, R.; Besin, E.; Palmieri, F.; Hodges, M. Molecular identification of three Arabidopsis thaliana mitochondrial dicarboxylate carrier isoforms: Organ distribution, bacterial expression, reconstitution into liposomes and functional characterization. Biochem. J. 2008, 410, 621–629.

- Hanson, A.D.; Gregory, J.F. Folate Biosynthesis, Turnover, and Transport in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2011, 62, 105–125.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!