Liver fibrosis is the consequence of different inflammatory processes occurring in any chronic liver disease. Its progression determines the development of cirrhosis and portal hypertension. The natural history of cirrhosis is characterized by a compensated phase, with or without portal hypertension, and a decompensated phase characterized by the appearance of major complications, such as ascites, portal hypertensive bleeding, encephalopathy, and jaundice. Malnutrition is frequent in patients with liver cirrhosis, which progresses in parallel with the worsening of the disease. Its etiology is multifactorial, given the great impact of liver disease on multiple processes related to nutrition.

- liver cirrhosis

- malnutrition

- malabsorption

- vitamins

- minerals

- sarcopenia

- liver transplant

- pancreatic exocrine insufficiency

- nutritional assessment

1. Consequences of Liver Disease on Nutritional Status

| Nutritional Consequence [Ref.] | Mechanisms in Chronic Liver Disease |

|---|---|

| 1. Impaired dietary intake [19,20] | Anorexia, dysgeusia, abdominal pain, bloating, early satiety secondary to ascites, prescription of restrictive diets, alcohol consumption |

| 2. Altered macro and micronutrient metabolism [13,14,15,16,21,22,23,24] | Lack of glycogen and vitamin storage, breakdown of fat and proteins as the principal energy source, decrease of vitamin and mineral levels |

| 3. Energy metabolism disturbances [25] | Hypermetabolic state, impaired glucose and lipid metabolism, sedentary lifestyle |

| 4. Increase in energy expenditure [26,27] | Increased catecholamines, malnutrition, immune compromise |

| 5. Nutrient malabsorption [28,29] | Decreased bile production, cholestasis, portosystemic shunting, portal hypertension gastropathy and enteropathy, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, drug-related diarrhea |

| 6. Sarcopenia and muscle function [30,31,32] | Proteolysis as the energy source, inhibition of muscle growth, muscle autophagy, proinflammatory state |

| 7. Metabolic osteopathy [33] | Decrease in bone formation, increased bone resorption, dysbiosis, vitamin K and D deficiencies |

1.1. Impaired Dietary Intake

1.2. Altered Macro and Micronutrients Metabolism

1.2.1. Plasma Proteins

1.2.2. Vitamins and Minerals

| Vitamin [Ref.] | Liver Role | Deficiency and Liver Disease | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fat-soluble vitamins | |||

| A (retinol) [14,15,16] | Production of RBP4 (transporter) Main storage in HSc (80%) |

Lost in vitamin A storage through the transformation of HSc into myofibroblasts. Deficiency is associated with nyctalopia (night blindness) and with hepatic encephalopathy | |

| D [14,15,16,22] | 25-hydroxylation site Production of binding proteins | Deficiency is associated with fibrosis, liver dysfunction, and mortality | |

| K [14,15,16] | Absorption of vitamin K trough bile acids | Deficiency is associated with coagulopathy and bone disease through an inadequate carboxylation of bone matrix proteins | |

| E [14,15,16] | Absorption of vitamin E trough bile acids | Deficiency is associated with hemolytic anemia, creatinuria, and neuronal degeneration | |

| Water-soluble vitamins | |||

| B [14,15,16] | B1 (thiamine) |

Normal thiamine function | Lost in activation and transport. Deficiency is associated with neurologic dysfunction (Wernicke encephalopathy) and high-output heart failure (wet beriberi) |

| B2 (riboflavin) |

Storage of riboflavin | Inadequate intake, increased utilization, and deficient storage. Deficiency is associated with inflammation of the gums and sores | |

| B6 (pyridoxine) |

Storage of pyridoxine | Deficiency is associated with anemia and neutropenia | |

| B9 (folate) |

Storage of folate | Deficiency is associated with anemia and macrocytosis | |

| B12 (cobalamin) |

Storage of cobalamin | Deficiency is associated with anemia and neutropenia | |

| C [14,15,16] | Storage of vitamin C | Deficiency is common in MAFLD. Deficiency is associated with bleeding, joint pain, and an increase of free radicals | |

| Minerals | |||

| Zinc (Zn) [14,15,16] | Absorption of Zn | Inadequate dietary intake, impaired absorption, and an increase in urinary loss. Deficiency is associated with hepatic encephalopathy and alterations in taste and smell | |

| Magnesium (Mg) [14,15,16] | Transport of Mg | Impaired transport and decrease intake. Deficiency is associated with dysgeusia, decreased appetite, muscle cramps, and weakness | |

| Manganese (Mn) [23] | Absorption trough bile acid production | Elevated if there is a decrease in biliary excretion Deficiency is associated with brain accumulation and parkinsonism |

|

| Carnitine [24] | Metabolism of carnitine | Poor intake. Deficiency is associated with muscle cramps | |

| Selenium (Se) [14,15,16] | Metabolism of Se | Deficiency related to severity liver disease Deficiency is associated with insulin resistance |

|

| Iron (Fe) [14,15,16] | Metabolism of Fe | Overload in alcoholic liver disease. Deficiency is associated with hepatic overload, fibrosis, and dysfunction | |

1.3. Energy Metabolism Disturbances

1.4. Increase in Energy Expenditure

1.5. Nutrient Malabsorption

1.6. Sarcopenia and Muscle Function

1.7. Metabolic Osteopathy

1.8. Interplay between MAFLD and Diet

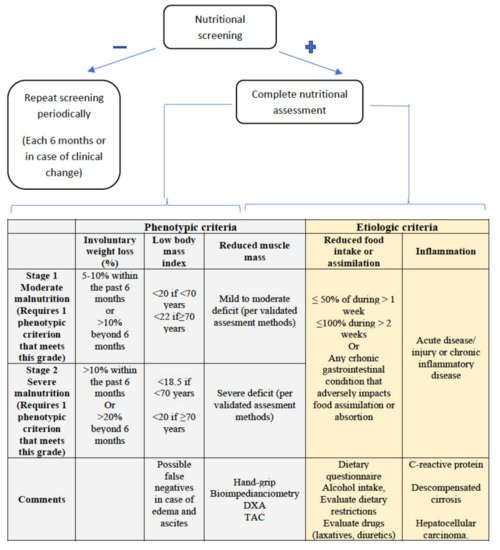

2. Nutritional Assessment of Patients with Chronic Liver Disease

2.1. Nutritional Screening and Risk of Malnutrition

| Screening Tool [Ref.] | Target Population | Variables | Strengths and Weaknesses | Usefulness in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MST [40] | Hospitalized patients | 1—Weight loss 2—Food intake 3—Appetite |

Quick and easy No calculations No training Self-administered |

May be inaccurate due to fluid overload. Low sensitivity in patients with liver cirrhosis. |

| MUST [41] | Hospitalized patients and outpatients | 1—BMI 2—Weight loss 3—Acute illness and impact on dietary |

Quick and easy Adds acute illness Offers advice |

May be inaccurate due to fluid overload. Low sensitivity in patients with liver cirrhosis. |

| MNA-SF [42] | Elderly patients | 1—Weight loss 2—Appetite 3—Mobility 4—Neuropsycho problems 5—BMI 6—Acute illness |

Full evaluation, not only nutritional aspects BMI can be replaced by calf diameter |

Good performance in liver cirrhosis. High sensitivity and good specificity. |

| NRS-2002 [43] | Hospitalized patients | 1—BMI 2—Weight loss 3—Food intake 4—Illness severity |

Adds illness severity and age | May be inaccurate due to fluid overload. Low sensitivity in liver cirrhosis. High specificity |

| CONUT [44] | Informatic tool Hospitalized patients and outpatients |

1—Albumin 2—Cholesterol 3—Lymphocytes 4—Age 5—Illness severity 6—Length of illness 7—Treatment |

Automated screening of large populations Blood test required Low specificity |

Predictor of survival and complications after liver resection. Predictor of survival in end-stage liver disease. |

| SNAQ [45] | Hospitalized patients and outpatients | 1—Weight loss 2—Appetite 3—Nutritional supplements 4—BMI 5—Albumin 6—Lymphocytes |

Simple and quick Provides a recommendation Blood test required |

Limited data on the population with liver cirrhosis, but correlation with the Child–Pugh stage. |

| RFH-NPT [46] | Patients with liver cirrhosis | 1—Transplant 2—Fluid overload 3—Weight loss 4—Food intake 5—BMI (in absence of fluid overload) 6—Acute illness |

Adds transplantation Reduces the impact of fluid retention Adds acute illness |

Superior results compared to other tests in liver cirrhosis. High sensitivity and specificity. |

| LDUST [45] | Patients with liver cirrhosis | 1—Food intake, 2—Weight loss 3—Body fat loss 4—Muscle mass loss 5—Fluid overload 6—Functional capability |

Reduces the impact of fluid retention Adds functional capacity Includes subjective variables |

Limited data in clinical practice. High sensitivity and specificity. |

2.2. Diagnosis of Malnutrition

2.2.1. Assessment of Reduced Intake

2.2.2. Weight Loss and Body Mass Index

2.2.3. Muscle Mass and Body Composition

2.2.4. Disease Burden/Inflammation

3. Nutritional Intervention in Liver Disease

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu13051650