Two major loci determining the resulting frost tolerance were identified on the long arm of group 5 chromosomes including Vrn1/Fr1 locus encoding the major vernalisation gene VRN1 induced by vernalisation fulfilment and Fr2 locus encoding a cluster of cold-inducible CBF transcription regulators upstream of COR/LEA genes.

- cold acclimation

- vernalisation

- frost tolerance

- dehydrins

- COR14b

- growth chambers

- field trials

1. Introduction

Low temperatures represent the dominant environmental factor determining plant growth and development during autumn/winter/spring seasons in temperate climates. Plants have evolved complex mechanisms aimed at an enhancement of their low-temperature tolerance in the process of cold acclimation [1]. In addition, plants growing in temperate climates where regular long periods of cold temperatures occur during the winter season have evolved developmental adaptation preventing a premature transition from more tolerant vegetative stage to cold-susceptible reproductive stage, i.e., complex mechanisms known as “vernalisation” [2]. In Triticeae, two major loci determining the resulting frost tolerance were identified on the long arm of group 5 chromosomes including Vrn1/Fr1 locus encoding the major vernalisation gene VRN1 induced by vernalisation fulfilment [3][4] and Fr2 locus encoding a cluster of cold-inducible CBF transcription regulators upstream of COR/LEA genes [5][6]. In the field, winter seasons in temperate zones are characterised not only by low temperatures but by multiple environmental stresses including freeze–thaw cycles, temporal floods during snow melting or winter drought. All these environmental stresses induce plant stress responses aimed at an enhancement of stress tolerance. Since low temperatures pose an enhanced risk of cellular dehydration and oxidative stress resulting from imbalances in photosynthesis, induction of enhanced low-temperature tolerance in plants is underlain by enhanced accumulation of several stress-protective proteins including several COR/LEA proteins including several COR/LEA proteins and dehydrins.

2. Cold Acclimation Studies in Controlled Conditions

Plants as poikilothermic organisms have to adjust their metabolism to ambient temperatures. Adjustment of chilling-tolerant and freezing-tolerant plants such as Triticeae cereals or winter oilseed rape to low above zero temperatures in the range 0–15 °C resulting in the acquisition of enhanced frost tolerance (FT) is known as cold acclimation (CA) [1][7]. Acquired FT is usually expressed as lethal temperature of 50% of the sample (LT50) which can be determined either by a direct frost test including regulated freezing and thawing of the samples in laboratory freezers [8] or by determination of tissue damage via electrolyte leakage [9]. The key inducing factors in plant cold acclimation process represent both low temperature (chilling) and photoperiod (short days) which determine chloroplast redox status and the activity of photosynthetic apparatus which provides energy for biosynthesis of novel molecules of transcripts, proteins and metabolites necessary for plant adaptation to altered environment [10]. CA appears to represent a modular response associated with alterations in nucleosomal histone H2A isoforms, indicating chromatin remodelling resulting in transcriptome and proteome reprogramming [11][12].

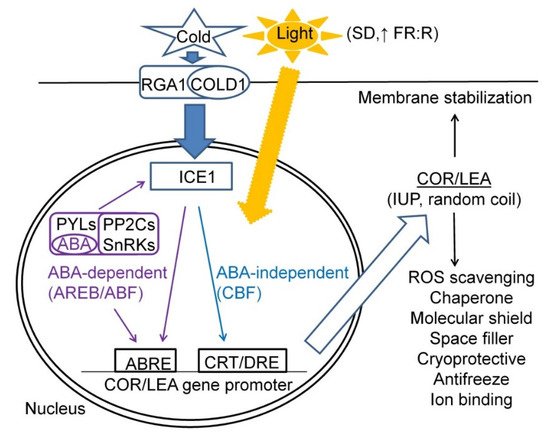

Cold acclimation (CA) thus represents a complex process of plant reversible adaptation to low temperatures aimed at enhancement of FT, which is associated with an enhanced accumulation of osmotically active compounds such as hydrophilic proteins from COR/LEA superfamily [13]; monosaccharides and oligosaccharides including sucrose and raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs) [14]; polyols; polyamines; etc. All these compounds bind water and stabilise membranes and other proteins upon CA [15]. In cold acclimation studies performed in controlled conditions such as growth chambers, plants are grown under defined photoperiod and temperature regimes which usually represent a continuous cold treatment resulting in an acquisition of maximum frost tolerance. Controlled conditions of growth chambers thus represent an ideal model for the study of the effects of cold on the expressions of cold-inducible CBF-COR/LEA genes (pathways). It is assumed that the primary cold signal arises at plasma membrane since low temperatures affect the physical properties and the final fluidity of phospholipid bilayer. Cold perception is probably performed by integral membrane proteins. Two-component histidine kinases with cytoplasmic kinase domain enabling signal transduction into cytoplasm and signal amplification have been proposed to confer cold sensing in cyanobacteria [16][17]. COLD1, identified in rice cv. Nipponbare, encodes a regulator of G protein signalling which is involved in chilling (0–15 °C) sensing and signal transduction via interaction with RGA1, the alpha subunit of a heterotrimeric G protein, and via calcium signalling [18]. An SNP2 in the fourth exon containing allele in COLD1 enhances its activation of G protein signalling, underlying enhanced chilling tolerance in japonica rice grown in temperate regions of Japan [18]. In the nucleus, cold-inducible signalling pathways can generally be divided into two major groups: ABA-dependent and ABA-independent. Under cold, COR/LEA gene expression is regulated by both ABA-dependent and ABA-independent pathways such as CBFs, as indicated by the presence of multiple copies of ABRE and CRT/DRE motifs in their promoters [19][20]. Moreover, both ABA-dependent and ABA-independent pathways reveal cross-talk in their regulation since ABA-induced kinase SnRK2 phosphorylates ICE1, which in turn activates CBF pathway [21][22]. Continuous cold treatments lead to significantly enhanced expression of CBF/COR pathway, indicated by COR/LEA transcript peaks at 3–4 days of cold treatment, while a slower rise of corresponding proteins results in a maximum at 2–3 weeks of cold treatment [23][24]. Moreover, organ-related differences in dehydrin protein relative accumulation were found by a comparison of leaf and crown tissues with crowns representing the crucial organ for whole plant survival [24]. Thus, determination of COR/LEA proteins in crown tissues in winter cereals seems to represent a useful approach for assessment of plant winter survival. Due to the high level of cold-induced dehydrin protein accumulation, their direct relationship to plant acquired frost tolerance was repeatedly found [25]. A correlation between dehydrin protein relative accumulation and plant acquired frost tolerance determined as LT50 was found not only for winter-type cereals such as winter wheats [26] and barleys [27] but also for other winter-type crops such as winter oilseed rape [28] when grown in controlled environment.

In addition to temperature, the CA process including the expression of some CBF-COR/LEA pathway genes and the resulting FT is affected by light including photoperiod, light intensity and light quality, i.e., the red to far-red (R:FR) light ratio [29][30]. Short-day (SD) photoperiods reveal inducing effects on CBF regulon, resulting in an enhanced accumulation of COR/LEA proteins and other cold-protective metabolites such as RFOs [14]. Moreover, relatively higher light irradiances favour CA in comparison to low irradiances since light is necessary for carbon assimilation and enhanced accumulation of protective compounds [31]. Ahres et al., [31] studied barley response to low temperatures (5 and 15 °C) and different light conditions including three light intensities and FR light supplementation on acquired FT and CBF14, COR14b and DHN5 transcript levels and found a significant response to both cold and light intensity and FR supplementation for CBF14 and chloroplast-located COR14b genes, while DHN5 responded only to cold. Studies aimed at a comparison of wheat Wcs120 or barley Dhn5 (Kn-type dehydrin) and Cor14b (LEA-III) gene expression revealed that Wcs120/Dhn5 expression pattern correlates well with cold-inducible CBFs expression and acquired FT, while the Cor14b expression pattern was more different from CBFs since it was also regulated by light [30][31].

There are differences between cold-tolerant (winter) and cold-susceptible (spring) genotypes in cereals (wheat and barley) related to CBF-COR/LEA pathway induction:

- (1)

-

Genetic differences: Cold-tolerant winter genotypes encode higher gene copy number of cold-inducible CBF genes at Fr2 locus when compared to cold-susceptible spring ones.The differential induction level of CBF/COR pathways between frost-tolerant and frost-susceptible genotypes can be determined genetically; for example, a comparative study by Tondelli et al., [32] revealed that frost-tolerant winter barley Nure has a higher CBF gene copy number in cold-inducible Fr2 locus than frost-susceptible spring barley Tremois. The differences in gene copy number of CBFs and other cold-inducible genes can thus underlie the differences in COR/LEA/dehydrin protein accumulation and the resulting frost tolerance between contrasting genotypes (e.g., spring vs. winter ones). Similarly, enhanced levels of WCBF2 TF and downstream Cor/Lea transcripts Wdhn13, Wcor14 and Wcor15 were found in frost-tolerant winter wheat Mironovskaya 808 in comparison to frost-susceptible spring wheat Chinese Spring; moreover, the transcript levels of WCBF2 as well as Wdhn13, Wcor14 and Wcor15 peaked later (at 42 days of cold treatment) in Mironovskaya 808 than in Chinese Spring (at 21 days of cold treatment) [33].

- (2)

-

Threshold induction temperatures: Fowler [34] showed that highly frost-tolerant winter cereals such as rye start inducing enhanced acquired frost tolerance determined as LT50 (lethal temperature for 50% of the samples) at higher growth temperatures in comparison with the less tolerant ones. Analogous patterns to LT50 were also found for cold-inducible CBFs and COR/LEA proteins, i.e., cold-tolerant winter cultivars start inducing cold-inducible genes such as CBFs and downstream COR/LEA proteins at higher temperatures in comparison with cold-susceptible ones. Vágújfalvi et al., [35] detected Cor14b transcripts in frost-tolerant winter line G3116 of einkorn wheat (T. monococcum) at higher temperature (up to 20 °C) than in frost-susceptible spring line DV92. Campoli et al., [36] detected different threshold induction temperatures for different CBF structural groups based on their phylogenetic analysis in winter barley, winter wheat, two winter rye and one spring rye cultivar. Similarly, Badawi et al., [37] distinguished ten CBF phylogenetic groups in two Triticum species, of which five Pooideae-specific groups revealed higher constitutive and low temperature inducible expression in winter wheat Norstar. Our previous studies [38][39] demonstrated that cold-inducible proteins such as wheat WCS120 or barley DHN5 can be detected in the highly frost-tolerant cultivars such as Mironovskaya 808 or Odesskij 31 at higher temperatures (17–20 °C) than in the less tolerant winter wheats or barleys (around 10 °C).

- (3)

-

Differential phytohormonal regulation of CA process: CA leads to repression of plant growth and development. In A. thaliana, Achard et al., [40] observed a positive effect of CBF1 on accumulation of DELLA proteins known as growth repressors due to stimulation of GA-2 oxidase resulting in reduction of active gibberellins (GA). Our comparative studies on winter wheat Samanta and spring wheat Sandra, winter wheat Cheyenne-Chinese Spring 5A substitution lines as well as einkorn wheats G3116 (facultative) and DV92 (spring) revealed similar patterns of FT (LT50) and dehydrins (COR14b and WCS120 family) induction during the first days of CA treatment; however, at later stages (21–42 days CA), spring genotypes revealed significantly lower FT and WCS120 proteins levels. Phytohormone analyses also revealed a two-phase CA response with an alarm and early acclimation phase (1–3 days CA) with increased ABA in all growth habits inducing stress acclimation response and later CA phases with differential responses (7–42 days) when winter types maintained high levels of stress acclimation-related phytohormones (ABA, JA and SA) while spring types revealed induction of phytohormones involved in vegetative-to-reproductive phase transition such as auxin, bioactive CKs and GAs probably due to VRN1 gene expression and floral meristem development [41][42][43]. Differential phytohormone dynamics may thus be the reason for lower FT and COR/LEA transcript/protein levels found in spring genotypes compared to winter ones at full CA (2–3 weeks CA treatment).

In the CA process, COR/LEA proteins play important roles of maintaining cell hydration, chaperone and other protective roles in interaction with other proteins and membranes; cryoprotective and antifreeze roles resulting in maintaining enzymatic activities under cold and modification of ice crystal growth under frost, respectively; and radical scavenging and ion binding functions. A scheme summarising the factors determining COR/LEA gene expression and their biological functions upon CA treatments is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A scheme summarising major factors and signalling pathways regulating COR/LEA gene expression and their biological functions in plant cells subjected to CA treatment.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/plants10040789

References

- Thomashow, M.F. Plant cold acclimation: Freezing tolerance genes and regulatory mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999, 50, 571–599.

- Chouard, P. Vernalization and its relations to dormancy. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1960, 11, 191–238.

- Fowler, D.B.; Breton, G.; Limin, A.E.; Mahfoozi, S.; Sarhan, F. Photoperiod and temperature interactions regulate low-temperature-induced gene expression in barley. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 1676–1681.

- Danyluk, J.; Kane, N.A.; Breton, G.; Limin, A.E.; Fowler, D.B.; Sarhan, F. TaVRT-1, a putative transcription factor associated with vegetative to reproductive transition in cereals. Plant Physiol. 2003, 132, 1849–1860.

- Francia, E.; Rizza, F.; Cattivelli, L.; Stanca, A.M.; Galiba, G.; Toth, B.; Hayes, P.M.; Skinner, J.S.; Pecchioni, N. Two loci on chromosome 5H determine low-temperature tolerance in a ‘Nure’ (winter) × ‘Tremois’ (spring) barley map. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 108, 670–680.

- Knox, A.K.; Li, C.X.; Vagujfalvi, A.; Galilba, G.; Stockinger, E.J.; Dubcovsky, J. Identification of candidate CBF genes for the frost tolerance locus Fr-A(m)2 in Triticum monococcum. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008, 67, 257–270.

- Ruelland, E.; Vaultier, M.N.; Zachowski, A.; Hurry, V. Cold signalling and cold acclimation in plants. Adv. Bot. Res. 2009, 49, 35–150.

- Janáček, J.; Prášil, I.T. Quantification of plant frost injury by nonlinear fitting of an S-shaped function. Cryo-Lett. 1991, 12, 47–52.

- Prášil, I.; Zámečník, J. The use of a conductivity measurement method for assessing freezing injury I. Influence of leakage time, segment number, size and shape in a sample on evaluation of the degree of injury. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1998, 40, 1–10.

- Gray, G.R.; Chauvin, L.P.; Sarhan, F.; Huner, N.P.A. Cold acclimation and freezing tolerance—A complex interaction of light and temperature. Plant Physiol. 1997, 114, 467–474.

- Kumar, S.V.; Wigge, P.A. H2A.Z-containing nucleosomes mediate the thermosensory response in Arabidopsis. Cell 2010, 140, 136–147.

- Janská, A.; Aprile, A.; Zámečník, J.; Cattivelli, L.; Ovesná, J. Transcriptional responses of winter barley to cold indicate nucleosome remodelling as a specific feature of crown tissues. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2011, 11, 307–325.

- Battaglia, M.; Olvera-Carrillo, Y.; Garciarrubio, A.; Campos, F.; Covarrubias, A.A. The enigmatic LEA proteins and other hydrophilins. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 6–24.

- Tarkowski, L.P.; Van den Ende, W. Cold tolerance triggered by soluble sugars: A multifaceted countermeasure. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 203.

- Bertrand, A.; Bipfubusa, M.; Claessens, A.; Rocher, S.; Castonguay, Y. Effect of photoperiod prior to cold acclimation on freezing tolerance and carbohydrate metabolism in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Plant Sci. 2017, 264, 122–128.

- Murata, N.; Los. D.A. Membrane fluidity and temperature perception. Plant Physiol. 1997, 115, 875–879.

- Suzuki, I.; Los, D.A.; Kanesaki, Y.; Mikami, K.; Murata, N. The pathway for perception and transduction of low-temperature signals in Synechocystis. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 1327–1334.

- Ma, Y.; Dai, X.; Xu, Y.; Luo, W.; Zheng, X.; Zeng, D.; Pan, Y.; Lin, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; et al. COLD1 confers chilling tolerance in rice. Cell 2015, 160, 1209–1221.

- Choi, D.W.; Zhu, B.; Close, T.J. The barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) dehydrin multigene family: Sequences, allele types, chromosome assignments, and expression characteristics of 11 Dhn genes of cv Dicktoo. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1999, 98, 1234–1247.

- Tommasini, L.; Svensson, J.T.; Rodriguez, E.M.; Wahid, A.; Malatrasi, M.; Kato, K.; Wanamaker, S.; Resnik, J.; Close, T.J. Dehydrin gene expression provides an indicator of low temperature and drought stress: Transcriptome-based analysis of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Funct. Integr. Genom. 2008, 8, 387–405.

- Zarka, D.G.; Vogel, J.T.; Cook, D.; Thomashow, M.F. Cold induction of Arabidopsis CBF genes involves multiple ICE (Inducer of CBF expression) promoter elements and a cold-regulatory circuit that is desensitized by low temperature. Plant Physiol. 2003, 133, 910–918.

- Ding, Y.L.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Xie, Q.; Gong, Z.Z.; Yang, S.H. OST1 kinase modulates freezing tolerance by enhancing ICE1 stability in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 2015, 32, 278–289.

- Ohno, R.; Takumi, S.; Nakamura, C. Kinetics of transcript and protein accumulation of a low-molecular-weight wheat LEA D-11 dehydrin in response to low temperature. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 160, 193–200.

- Ganeshan, S.; Vítámvás, P.; Fowler, D.B.; Chibbar, R.N. Quantitative expression analysis of selected COR genes reveals their differential expression in leaf and crown tissues of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) during an extended low temperature acclimation regimen. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 2393–2402.

- Houde, M.; Dhindsa, R.S.; Sarhan, F. A molecular marker to select for freezing tolerance in Gramineae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1992, 234, 43–48.

- Vítámvás, P.; Saalbach, G.; Prášil, I.T.; Čapková, V.; Opatrná, J.; Ahmed, J. WCS120 protein family and proteins soluble upon boiling in cold-acclimated winter wheat. J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 164, 1197–1207.

- Kosová, K.; Holková, L.; Prášil, I.T.; Prášilová, P.; Bradáčová, M.; Vitámvás, P.; Čapková, V. Expression of dehydrin 5 during the development of frost tolerance in barley (Hordeum vulgare). J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 1142–1151.

- Urban, M.O.; Klíma, M.; Vítámvás, P.; Vašek, J.; Hilgert-Delgado, A.A.; Kučera, V. Significant relationships among frost tolerance and net photosynthetic rate, water use efficiency and dehydrin accumulation in cold-treated winter oilseed rapes. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 170, 1600–1608.

- Crosatti, C.; de Laureto, P.P.; Bassi, R.; Cattivelli, L. The interaction between cold and light controls the expression of the cold-regulated barley gene cor14b and the accumulation of the corresponding protein. Plant Physiol. 1999, 119, 671–680.

- Maibam, P.; Nawkar, G.M.; Park, J.H.; Sahi, V.P.; Lee, S.Y.; Kang, C.H. The influence of light quality, circadian rhythm, and photoperiod on the CBF-mediated freezing tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 11527–11543.

- Ahres, M.; Gierczik, K.; Boldizsár, A.; Vítámvás, P.; Galiba, G. Temperature and light-quality dependent regulation of freezing tolerance in barley. Plants 2020, 9, 83.

- Tondelli, A.; Francia, E.; Barabaschi, D.; Pasquariello, M.; Pecchioni, N. Inside the CBF locus in Poaceae. Plant Sci. 2011, 180, 39–45.

- Kume, S.; Kobayashi, F.; Ishibashi, M.; Ohno, R.; Nakamura, C.; Takumi, S. Differential and coordinated expression of Cbf and Cor/Lea genes during long-term cold acclimation in two wheat cultivars showing distinct levels of freezing tolerance. Genes Genet. Syst. 2005, 80, 185–197.

- Fowler, D.B. Cold acclimation threshold induction temperatures in cereals. Crop Sci. 2008, 48, 1147–1154.

- Vágújfalvi, A.; Galiba, G.; Cattivelli, L.; Dubcovsky, J. The cold-regulated transcriptional activator Cbf3 is linked to the frost-tolerance locus Fr-A2 on wheat chromosome 5A. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2003, 269, 60–67.

- Campoli, C.; Matus-Cadiz, M.A.; Pozniak, C.J.; Cattivelli, L.; Fowler, D.B. Comparative expression of Cbf genes in the Triticeae under different acclimation induction temperatures. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2009, 282, 141–152.

- Badawi, M.; Danyluk, J.; Boucho, B.; Houde, M.; Sarhan, F. The CBF gene family in hexaploid wheat and its relationship to the phylogenetic complexity of cereal CBFs. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2007, 277, 533–554.

- Vítámvás, P.; Kosová, K.; Prášilová, P.; Prášil, I.T. Accumulation of WCS120 protein in wheat cultivars grown at 9 °C or 17 °C in relation to their winter survival. Plant Breed. 2010, 129, 611–616.

- Kosová, K.; Vitámvás, P.; Prášilová, P.; Prášil, I.T. Accumulation of WCS120 and DHN5 proteins in differently frost-tolerant wheat and barley cultivars grown under a broad temperature scale. Biol. Plant 2013, 57, 105–112.

- Achard, P.; Gong, F.; Cheminant, S.; Alioua, M.; Hedden, P.; Genschik, P. The cold-inducible CBF1 factor-dependent signaling pathway modulates the accumulation of the growth-repressing DELLA proteins via its effect on gibberellin metabolism. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 2117–2129.

- Kosová, K.; Prášil, I.T.; Vítámvás, P.; Dobrev, P.; Motyka, V.; Floková, K.; Novák, O.; Turečková, V.; Rolčik, J.; Pešek, B.; et al. Complex phytohormone responses during the cold acclimation of two wheat cultivars differing in cold tolerance, winter Samanta and spring Sandra. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169, 567–576.

- Vanková, R.; Kosová, K.; Dobrev, P.; Vítámvás, P.; Trávníčková, A.; Cvikrová, M.; Pešek, B.; Gaudinová, A.; Přerostová, S.; Musilová, J.; et al. Dynamics of cold acclimation and complex phytohormone responses in Triticum monococcum lines G3116 and DV92 differing in vernalization and frost tolerance level. Env. Exp. Bot. 2014, 101, 12–25.

- Kalapos, B.; Novák, A.; Dobrev, P.; Vítámvás, P.; Marincs, F.; Galiba, G.; Vanková, R. Effect of the winter wheat Cheyenne 5A substituted chromosome on dynamics of abscisic acid and cytokinins in freezing-sensitive Chinese spring genetic background. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2033.