Koala retrovirus (KoRV) is assumed to cause immunosuppression and neoplastic diseases, favoring chlamydiosis in koalas. Koala populations are currently declining and under threat from KoRV infection both in the wild and in captivity. Currently, 10 KoRV subtypes have been identified, including an endogenous subtype (KoRV-A) and nine exogenous subtypes (KoRV-B to KoRV-J). The host’s immune response acts as a safeguard against pathogens. Therefore, a proper understanding of the immune response mechanisms against infection is of great importance for the host’s survival, as well as for the development of therapeutic and prophylactic interventions. A vaccine is an important protective as well as being a therapeutic tool against infectious disease, and several studies have shown promise for the development of an effective vaccine against KoRV. Moreover, CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing has opened a new window for gene therapy, and it appears to be a potential therapeutic tool in many viral infections, which could also be investigated for the treatment of KoRV infection.

- koala

- koala retrovirus

- toll-like receptors

- cytokines

- immune response

- vaccines

1. Introduction

The koala (Phascolarctos cinereus), an iconic marsupial of Australia, is facing severe population decline due to man-made hazards and natural infections [1][2]. Koala retrovirus (KoRV) is considered to be one of the major infectious agents in koala populations impacting koala health both in the wild and in captivity [3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11]. The replication-competent full genome sequence of KoRV was reported in 2000 [12]. KoRV, a single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus, belongs to the Retroviridae family and the Gammaretrovirus genus, with a genome of 8.4 kb containing gag, pol, and env genes, and an integrated KoRV provirus additionally contains long terminal repeats at both ends [4][12][13]. KoRV has the typical morphology of a gammaretrovirus, which consists of spherically shaped virions ranging between 80 and 100 nm in diameter [14]. Recently, KoRV gained the interest of many virologists due to its unique feature of existing in both exogenous and endogenous forms, providing a unique opportunity to gain insights into how retroviruses infect their new host and evolve together in the early stages of genome invasion [15].

Although endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) are ubiquitous features of mammalian genomes, in contrast to other mammalian species the endogenization process of KoRV is a relatively recent event, having started approximately 22,000 to 49,000 years ago or more recently, and is assumed to be still ongoing [13][16]. Several studies have indicated the existence of ongoing retroviral invasion of the koala germline [15][16][17]. Evolutionarily, KoRV and the gibbon ape leukemia virus are very closely related [18], and other close relatives of KoRV include feline leukemia virus (FeLV) [14], porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV) [14], and melomys burtoni retrovirus (MbRV) [19]. In terms of transmission, KoRV shows some resemblance to other retroviruses. KoRV infection is a recent trans-species transmission event in koalas [20]; however, from which species the virus jumped into koalas is yet unknown. A native Australian rodent, the grassland melomys (Melomys burtoni) has been considered as one of the candidate species [18][19], and recently bats were also suggested [21]. Until now, 10 different KoRV subtypes (KoRV-A to KoRV-J) have been reported, where KoRV-A is assumed to exist as both endogenous and exogenous forms, and the other subtypes (KoRV-B to KoRV-J) are considered to be exogenous [10]. KoRV-A and KoRV-B have been characterized most extensively; however, the other subtypes largely remain to be characterized [2][22]. The entry receptors utilized by KoRV-A and KoRV-B are different, where KoRV-A uses a phosphate transporter (PiT1) [23], and KoRV-B uses thiamine transporter 1 (ThTR1) [5][24]; however, the entry receptors for the other subtypes (KoRV-C to KoRV-I) have not been identified. As reported previously, KoRV prevalence varies based on the geographical location of a particular population [25]. As observed, KoRV-A has 100% prevalence in northern Australian koala populations, indicating that KoRV-A has been fully endogenized in northern koalas [22]. However, there is little or no evidence for endogenization in southern koala populations, but the prevalence of KoRV is on the increase in southern koalas [22][26][27]. In a recent study, Hobbs et al. reported defective KoRV-D and KoRV-E subtypes in koalas with significant deletions in the gag and pol genes [15]. ERV and exogenous retrovirus (XRV) interactions by recombination may generate ERV-XRV chimeras [28]. Recently, many recombinant KoRVs (recKoRV) were reported in koalas [15][29][30]. In addition, Löber et al. showed that recombination with an ancient koala retroelement disables KoRV, which frequently occurs at an early point in the invasion process [29].

Different evolutionary, epidemiological, immunological, and clinical aspects of KoRV infection in koala populations have been reviewed in several previous studies [2][14][20][22][31][32][33][34][35][36].

2. Maintenance of Koala Health and Conservation by Vaccine Development and the Investigation of Alternative Strategies

2.1. Vaccine Response in Koalas against KoRV

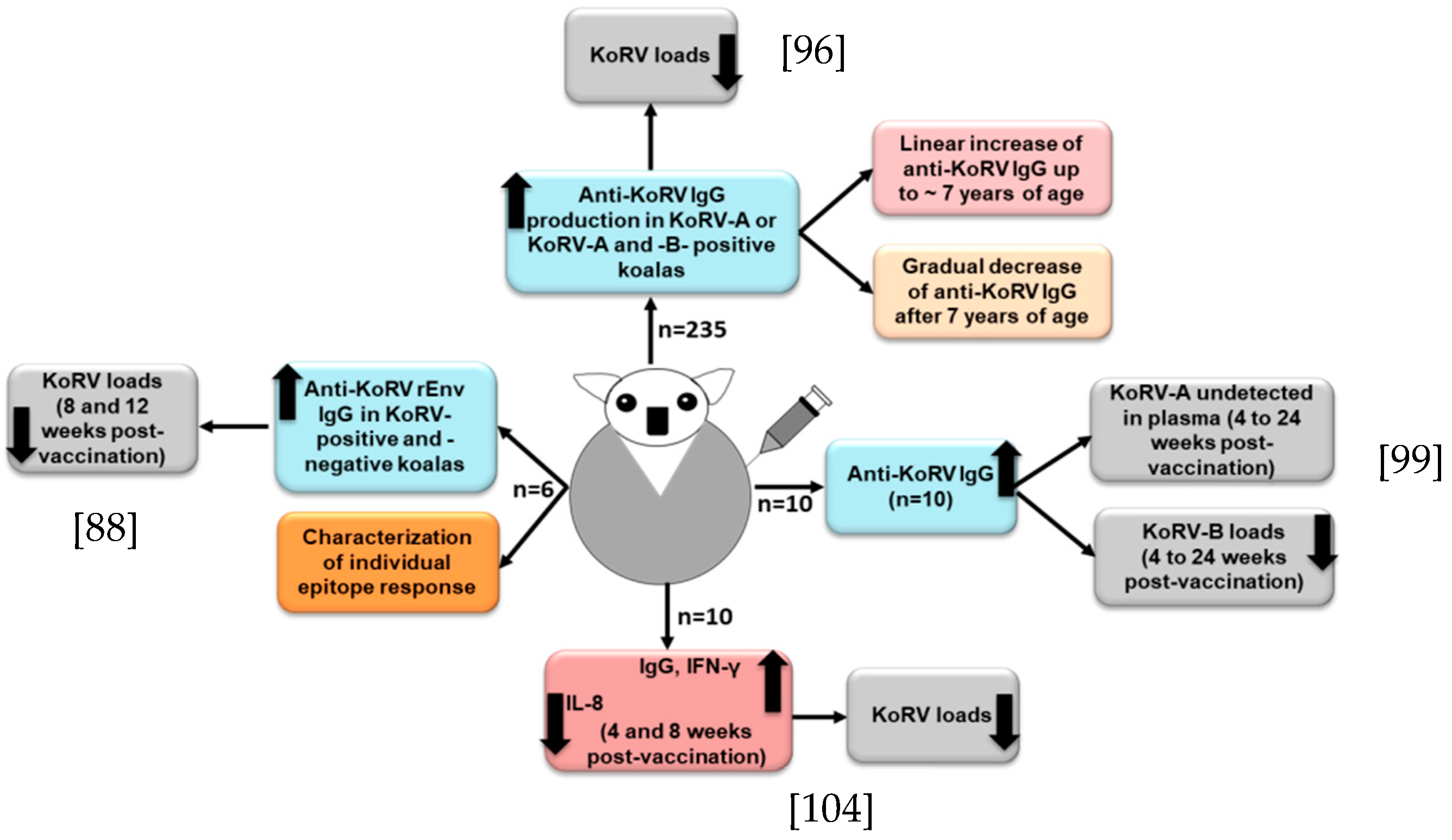

For the maintenance of koala health and conservation, effective prophylactic vaccines against the exogenous KoRV subtypes are in urgent need of development. Although it is challenging to develop a successful vaccine against a retrovirus [37], an effective vaccine against FeLV (a gammaretrovirus) infection has been developed [38], which may suggest that vaccine development for KoRV might be feasible. However, during the exploration of the antibody response, Fiebig et al. found a lack of antibody response in 16 northern koalas, which might suggest a state of tolerance in those koalas [39]. Towards a continued effort of developing a prophylactic KoRV vaccine, Fiebig et al. observed that a recombinant KoRV (rKoRV) Env protein could induce neutralizing antibodies in rats and goats [40]. In a subsequent study with three northern koalas, a recombinant KoRV-A Env vaccine induced Env antibodies, and the vaccinated koalas did not show any sign of adverse reactions [41]. In another study, Olagoke et al. selected recombinant KoRV envelope protein (rEnv) as the vaccine antigen by epitope mapping analysis, which consisted of a segment of KoRV env protein and a synthetic membrane proximal external region (MPER) peptide [42]. MPER is considered to be an attractive vaccine target due to its conserved nature and induction of broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) [43][44]. The rEnv -based anti-KoRV vaccine induced a significant humoral immune response and neutralizing antibodies in both KoRV-positive (KoRV-A positive, but KoRV-B negative) and KoRV-negative koalas [42]. In order to further investigate, Olagoke et al. performed a large-scale study with 235 wild koalas harboring KoRV-A with or without KoRV-B, and found the production of anti-KoRV antibodies in about 95% of the vaccinated koalas [45] (Figure 1); antibody production against endogenous KoRV could partly explained by the role of Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) in koalas [17]. There was an association between koala age and the production of anti-KoRV IgG levels upon vaccination, where a linear increase of anti-KoRV IgG level was observed up to 7 years of age, and there was a gradual decrease of anti-KoRV IgG level after 7 years of age (Figure 1) [45], which could be partly explained by the reduction of the functional innate immune cell numbers that are related to aging [46].

Figure 1. Cartoon shows KoRV vaccine responses in KoRV-infected koalas. In each case [42][45][47][48], anti-KoRV IgGs were developed and viral loads were reduced.

It is notable to mention that, in our recent study, we observed a high KoRV RNA load in the plasma of one koala, and when it was tested again after several months, that koala became negative for KoRV [49], which might be due to the induction of the immune response that finally cleared the KoRV from the plasma [50]. Olagoke et al. further reported that therapeutic vaccination with a recombinant KoRV Env protein combined with a Tri-adjuvant in koalas infected with endogenous retrovirus induced anti-KoRV IgG and neutralizing antibodies and resulted in a complete clearance of KoRV-A from the plasma. Moreover, there was a decreased KoRV-B viral RNA level in plasma, which is suggestive of the induction of cross-reactive antibodies [47] (Figure 1). Its efficacy against other exogenous KoRV subtypes should also be investigated.

A proper understanding of koala’s immune response against KoRV is a key step in therapeutic and prophylactic interventions for better conservation and management strategies to protect koalas. Moreover, deciphering the role of TLRs in the adaptive immune response could be an important area of future study [51]. A balanced cellular and humoral immune response is essential for preventing retrovirus infection [37]. It has been reported that both the innate and adaptive immune response play important roles in the control of ERVs in mice [52][53]. The innate immune response induces a rapid inflammatory cytokine burst and activates antigen-presenting cells, which play an important role in the conditioning of the immune system for the further development of a specific adaptive immune response [54]. A recent study investigated the expression profiles of key immune genes upon vaccination, and observed a significant upregulation of interferon-γ (IFN- γ) and decreased IL-8 expression (Figure 1); however, no significant changes in the mRNA expression of CCL4L, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-18, IL-4, and IL-6 were observed at either 4- or 8-weeks post-vaccination [48]. Both the cell-mediated and humoral immune response were induced, and viral loads were decreased [48]. However, the koalas used in that study had very low CD4 levels compared to their CD8β levels, which might be linked to KoRV infection; however, the vaccination did not improve the condition, which is important to investigate in a future study. Olagoke et al. also observed an expression of four host restriction factors, such as BST2, ISG15, RSAD2 and TRIM1, in endogenous KoRV harboring koalas, with a relatively higher expression of BST2, ISG15 and RSAD2, which is suggestive of the biological importance of these restriction factors in koalas [48]. Different restriction factors have been identified in humans and animals that are known to inhibit virus replication [55]. However, the roles of these restriction factors in koalas remain to be investigated.

Although there have been many advances towards vaccine development, the efficacy of the KoRV vaccines against multiple KoRV subtype infections, including KoRV C to J, remains to be investigated. Moreover, it has been reported that purified TLR agonists could be used as adjuvants in vaccination to enhance the adaptive response [56], which could be investigated in koalas, particularly where the antibody response is poor or lacking [39]. However, the development of an effective pan-subtypic KoRV vaccine is a major area of interest for protecting koala health. Moreover, the advances of KoRV vaccine development would benefit the field of other retrovirus vaccine development.

2.2. Alternative Strategies to Control KoRV Infection

It is of great importance to investigate for alternative strategies to avoid KoRV threats to koala health and conservation. piRNAs are a distinct class of small non-coding RNAs, which are 24–31 nucleotides in length and can silence transposable elements, regulate gene expression, and fight viral infection [57][58]. In order to prevent deleterious germline mutations, it is important to suppress the active replication of ERVs and virus-like elements in the germ line. However, ERV and retrotransposon activities are not limited to the germline only; they also occur in somatic tissues and can induce disease [59][60][61]. PiRNAs play an important role in the maintenance of genomic stability of many animal species. piRNAs form the piRNA-induced silencing complex (piRISC) in the germ line, and they protect the integrity of the genome from invasion of transposable elements (TEs) by silencing them [62][63].

piRNA-mediated silencing has been shown to be important for the repression of TEs activity in mouse germ cells [62]. Therefore, it is of great interest to investigate the evolutionary control of KoRV infection in koalas by characterizing piRNAs. The piRNA pathway is a conserved defense mechanism that functions as a safeguard of genome integrity and the fertility of animal germ cells [64]. In a recent study, Yu et al. characterized koala piRNAs, and transposon-mapping revealed that piRNAs in koala are roughly equally sense- and antisense-oriented, with a typical 1U and ping-pong signatures [17]. They found that KoRV-A and three endogenous retrotransposons are active in the koala germline and soma; however, their activities were lower in the testis compared to somatic tissues, where the piRNA pathway is active [17]. They also observed that unspliced KoRV-A proviral transcripts are preferentially processed into piRNAs, and the piRNA emerging from unspliced transposon transcripts is deeply conserved [17]. More importantly, in that study, they indicated the role of piRNAs in responding against KoRV germline invasion, where both the innate and adaptive phases of piRNA response were generated [17]. However, in order to gain further insights into KoRV-A association in endogenous transposon mobilization, KoRV-free animals could be investigated, which are present in the southern end of the koala habitat [22].

Recently, Tarlinton et al. reported that koalas may maintain defective KoRV as protection from the infectious form of KoRV, and those koalas could be selectively used for breeding in order to avoid the threat of infectious KoRV [65]. CRISPR/Cas9 appears to be a revolutionary genome editing tool which could be used in the control of viral infections [66]. Recently, Yang et al. succeeded in inactivating PERV in a porcine kidney epithelial cell line (PK15) using CRISPR-Cas9 by targeting the PERV pol gene [67]. In a subsequent study, Niu et al. became able to inactivate all of the PERVs in a porcine primary cell line using CRISPR-Cas9 technology, and developed PERV-inactivated pigs via somatic cell nuclear transfer [68]. Using a combination of CRISPR-Cas9 and transposon technologies, Yue et al. performed an extensive germline genome engineering in pigs, and showed the inactivation of all the PERV in pigs [69]. These findings also show the suitability of utilizing CRISPR/Cas9 technology to control KoRV infection in koalas, and future study in this regard is warranted.

3. Conclusions

The understanding about the interactions of KoRV and its host is advancing. However, a thorough study of the host immune response against multiple KoRV subtypes could aid further insights into the understanding of the potential of KoRV in the host’s immunopathogenesis, as well as prophylactic and therapeutic KoRV vaccine development, which will be a big step towards koala health and conservation strategies. Moreover, the deep transcriptome analysis of koala populations from different geographic locations is of great importance to further deciphering any underlying genetic components’ effects on koala health and conservation [70].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cimb43010005

References

- Melzer, A.; Carrick, F.; Menkhorst, P.; Lunney, D.; John, B.S. Overview, critical assessment, and conservation implications of koala distribution and abundance. Conserv. Biol. 2000, 14, 619–628.

- Quigley, B.L.; Timms, P. Helping koalas battle disease–Recent advances in Chlamydia and koala retrovirus (KoRV) disease understanding and treatment in koalas. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 44, 583–605.

- Connolly, J.H.; Canfield, P.J.; Hemsley, S.; Spencer, A.J. Lymphoid neoplasia in the koala. Aust. Vet. J. 1998, 76, 819–825.

- Tarlinton, R.; Meers, J.; Hanger, J.; Young, P. Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR for the endogenous koala retrovirus reveals an association between plasma viral load and neoplastic disease in koalas. J. Gen. Virol. 2005, 86, 783–787.

- Xu, W.; Stadler, C.K.; Gorman, K.; Jensen, N.; Kim, D.; Zheng, H.Q.; Tang, S.; Switzer, W.M.; Pye, G.W.; Eiden, M.V. An exogenous retrovirus isolated from koalas with malignant neoplasias in a US zoo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 11547–11552.

- Waugh, C.A.; Hanger, J.; Loader, J.; King, A.; Hobbs, M.; Johnson, R.; Timms, P. Infection with koala retrovirus subgroup B (KoRV-B), but not KoRV-A, is associated with chlamydial disease in free-ranging koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 134.

- Fabijan, J.; Woolford, L.; Lathe, S.; Simmons, G.; Hemmatzadeh, F.; Trott, D.J.; Speight, K.N. Lymphoma, koala retrovirus infection and reproductive chlamydiosis in a koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). J. Comp. Pathol. 2017, 157, 188–192.

- Quigley, B.L.; Phillips, S.; Olagoke, O.; Robbins, A.; Hanger, J.; Timms, P. Changes in endogenous and exogenous koala retrovirus subtype expression over time reflect koala health outcomes. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00849-19.

- Hashem, M.A.; Kayesh, M.E.H.; Yamato, O.; Maetani, F.; Eiei, T.; Mochizuki, K.; Sakurai, H.; Ito, A.; Kannno, H.; Kohara, K.T.; et al. Coinfection with koala retrovirus subtypes A and B and its impact on captive koalas in Japanese zoos. Arch. Virol. 2019, 164, 2735–2745.

- Zheng, H.; Pan, Y.; Tang, S.; Pye, G.W.; Stadler, C.K.; Vogelnest, L.; Herrin, K.V.; Rideout, B.A.; Switzer, W.M. Koala retrovirus diversity, transmissibility, and disease associations. Retrovirology 2020, 17, 34.

- Hashem, M.A.; Kayesh, M.E.H.; Maetani, F.; Eiei, T.; Mochizuki, K.; Ochiai, S.; Ito, A.; Ito, N.; Sakurai, H.; Asai, T.; et al. Koala retrovirus (KoRV) subtypes and their impact on captive koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) health. Arch. Virol. 2021. (Accepted).

- Hanger, J.J.; Bromham, L.D.; McKee, J.J.; O’Brien, T.M.; Robinson, W.F. The nucleotide sequence of Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) retrovirus: A novel type C endogenous virus related to Gibbon ape leukemia virus. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 4264–4272.

- Tarlinton, R.E.; Meers, J.; Young, P.R. Retroviral invasion of the koala genome. Nature 2006, 442, 79–81.

- Denner, J.; Young, P.R. Koala retroviruses: Characterization and impact on the life of koalas. Retrovirology 2013, 10, 108.

- Hobbs, M.; King, A.; Salinas, R.; Chen, Z.; Tsangaras, K.; Greenwood, A.D.; Johnson, R.N.; Belov, K.; Wilkins, M.R.; Timms, P. Long-read genome sequence assembly provides insight into ongoing retroviral invasion of the koala germline. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15838.

- Ishida, Y.; Zhao, K.; Greenwood, A.D.; Roca, A.L. Proliferation of endogenous retroviruses in the early stages of a host germ line invasion. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 109–120.

- Yu, T.; Koppetsch, B.S.; Pagliarani, S.; Johnston, S.; Silverstein, N.J.; Luban, J.; Chappell, K.; Weng, Z.; Theurkauf, W.E. The piRNA Response to Retroviral Invasion of the Koala Genome. Cell 2019, 179, 632–643.e12.

- Alfano, N.; Michaux, J.; Fabre, P.H.; Morand, S.; Alpin, K.; Tsangaras, K.; Löber, U.; Fitriana, Y.; Semiadi, G.; Ishida, Y.; et al. Endogenous gibbon ape leukemia virus identified in a rodent (Melomys burtoni subsp.) from Wallacea (Indonesia). J. Virol. 2016, 90, 8169–8180.

- Simmons, G.; Clarke, D.; McKee, J.; Young, P.; Meers, J. Discovery of a novel retrovirus sequence in an Australian native rodent (Melomys burtoni): A putative link between gibbon ape leukemia virus and koala retrovirus. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106954.

- Greenwood, A.D.; Ishida, Y.; O’Brien, S.P.; Roca, A.L.; Eiden, M.V. Transmission, Evolution, and Endogenization: Lessons Learned from Recent Retroviral Invasions. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2017, 82, e00044-17.

- Hayward, J.A.; Tachedjian, M.; Kohl, C.; Johnson, A.; Dearnley, M.; Jesaveluk, B.; Langer, C.; Solymosi, P.D.; Hille, G.; Nitsche, A.; et al. Infectious KoRV-related retroviruses circulating in Australian bats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 9529–9536.

- Kayesh, M.E.H.; Hashem, M.A.; Tsukiyama-Kohara, K. Koala retrovirus epidemiology, transmission mode, pathogenesis, and host immune response in koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus): A review. Arch. Virol. 2020, 165, 2409–2417.

- Oliveira, N.M.; Farrell, K.B.; Eiden, M.V. In vitro characterization of a koala retrovirus. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 3104–3107.

- Shojima, T.; Yoshikawa, R.; Hoshino, S.; Shimode, S.; Nakagawa, S.; Ohata, T.; Nakaoka, R.; Miyazawa, T. Identification of a novel subgroup of Koala retrovirus from Koalas in Japanese zoos. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 9943–9948.

- Simmons, G.S.; Young, P.R.; Hanger, J.J.; Jones, K.; Clarke, D.; McKee, J.J.; Meers, J. Prevalence of koala retrovirus in geographically diverse populations in Australia. Aust. Vet. J. 2012, 90, 404–409.

- Fabijan, J.; Miller, D.; Olagoke, O.; Woolford, L.; Boardman, W.; Timms, P.; Polkinghorne, A.; Simmons, G.; Hemmatzadeh, F.; Trott, D.J.; et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of koala retrovirus in two South Australian koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) populations. J. Med. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 1072–1080.

- Sarker, N.; Fabijan, J.; Seddon, J.; Tarlinton, R.; Owen, H.; Simmons, G.; Thia, J.; Blanchard, A.M.; Speight, N.; Kaler, J.; et al. Genetic diversity of Koala retrovirus env gene subtypes: Insights into northern and southern koala populations. J. Gen. Virol. 2019, 100, 1328–1339.

- Chiu, E.S.; VandeWoude, S. Endogenous Retroviruses Drive Resistance and Promotion of Exogenous Retroviral Homologs. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2021, 9, 225–248.

- Löber, U.; Hobbs, M.; Dayaram, A.; Tsangaras, K.; Jones, K.; Alquezar-Planas, D.E.; Ishida, Y.; Meers, J.; Mayer, J.; Quedenau, C.; et al. Degradation and remobilization of endogenous retroviruses by recombination during the earliest stages of a germ-line invasion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8609–8614.

- Johnson, R.N.; O’Meally, D.; Chen, Z.; Etherington, G.J.; Ho, S.Y.W.; Nash, W.J.; Grueber, C.E.; Cheng, Y.; Whittington, C.M.; Dennison, S.; et al. Adaptation and conservation insights from the koala genome. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1102–1111.

- Stoye, J.P. Koala retrovirus: A genome invasion in real time. Genome Biol. 2006, 7, 241.

- Denner, J. Transspecies transmissions of retroviruses: New cases. Virology 2007, 369, 229–233.

- Tarlinton, R.; Meers, J.; Young, P. Biology and evolution of the endogenous koala retrovirus. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 3413–3421.

- Xu, W.; Eiden, M.V. Koala Retroviruses: Evolution and Disease Dynamics. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2015, 2, 119–134.

- Kinney, M.E.; Pye, G.W. KOALA RETROVIRUS: A REVIEW. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2016, 47, 387–396.

- Madden, D.; Whaite, A.; Jones, E.; Belov, K.; Timms, P.; Polkinghorne, A. Koala immunology and infectious diseases: How much can the koala bear? Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2018, 82, 177–185.

- Vaine, M.; Lu, S.; Wang, S. Progress on the induction of neutralizing antibodies against HIV type 1 (HIV-1). BioDrugs 2009, 23, 137–153.

- Osterhaus, A.; Weijer, K.; UytdeHaag, F.; Knell, P.; Jarrett, O.; Akerblom, L.; Morein, B. Serological responses in cats vaccinated with FeLV ISCOM and an inactivated FeLV vaccine. Vaccine 1989, 7, 137–141.

- Fiebig, U.; Keller, M.; Möller, A.; Timms, P.; Denner, J. Lack of antiviral antibody response in koalas infected with koala retroviruses (KoRV). Virus Res. 2015, 198, 30–34.

- Fiebig, U.; Dieckhoff, B.; Wurzbacher, C.; Möller, A.; Kurth, R.; Denner, J. Induction of neutralizing antibodies specific for the envelope proteins of the koala retrovirus by immunization with recombinant proteins or with DNA. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 68.

- Waugh, C.; Gillett, A.; Polkinghorne, A.; Timms, P. Serum antibody response to koala retrovirus antigens varies in free-ranging koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) in Australia: Implications for vaccine design. J. Wildl. Dis. 2016, 52, 422–425.

- Olagoke, O.; Miller, D.; Hemmatzadeh, F.; Stephenson, T.; Fabijan, J.; Hutt, P.; Finch, S.; Speight, N.; Timms, P. Induction of neutralizing antibody response against koala retrovirus (KoRV) and reduction in viral load in koalas following vaccination with recombinant KoRV envelope protein. NPJ Vaccines 2018, 3, 30.

- Montero, M.; van Houten, N.E.; Wang, X.; Scott, J.K. The membrane-proximal external region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope: Dominant site of antibody neutralization and target for vaccine design. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2008, 72, 54–84.

- Molinos-Albert, L.M.; Clotet, B.; Blanco, J.; Carrillo, J. Immunologic Insights on the Membrane Proximal External Region: A Major Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type-1 Vaccine Target. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1154.

- Olagoke, O.; Quigley, B.L.; Eiden, M.V.; Timms, P. Antibody response against koala retrovirus (KoRV) in koalas harboring KoRV-A in the presence or absence of KoRV-B. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12416.

- Gubbels Bupp, M.R.; Potluri, T.; Fink, A.L.; Klein, S.L. The Confluence of Sex Hormones and Aging on Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1269.

- Olagoke, O.; Quigley, B.L.; Hemmatzadeh, F.; Tzipori, G.; Timms, P. Therapeutic vaccination of koalas harbouring endogenous koala retrovirus (KoRV) improves antibody responses and reduces circulating viral load. NPJ Vaccines 2020, 5, 60.

- Olagoke, O.; Quigley, B.L.; Timms, P. Koalas vaccinated against Koala retrovirus respond by producing increased levels of interferon-gamma. Virol. J. 2020, 17, 168.

- Hilleman, M.R. Vaccines in historic evolution and perspective: A narrative of vaccine discoveries. Vaccine 2000, 18, 1436–1447.

- Kayesh, M.E.H.; Yamato, O.; Rahman, M.M.; Hashem, M.A.; Maetani, F.; Eiei, T.; Mochizuki, K.; Sakurai, H.; Tsukiyama-Kohara, K. Molecular dynamics of koala retrovirus infection in captive koalas in Japan. Arch Virol. 2019, 164, 757–765.

- Iwasaki, A.; Medzhitov, R. Regulation of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Science 2010, 327, 291–295.

- Young, G.R.; Eksmond, U.; Salcedo, R.; Alexopoulou, L.; Stoye, J.P.; Kassiotis, G. Resurrection of endogenous retroviruses in antibody-deficient mice. Nature 2012, 491, 774–778.

- Yu, P.; Lübben, W.; Slomka, H.; Gebler, J.; Konert, M.; Cai, C.; Neubrandt, L.; Prazeres da Costa, O.; Paul, S.; Dehnert, S.; et al. Nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors are essential for the control of endogenous retrovirus viremia and ERV-induced tumors. Immunity 2012, 37, 867–879.

- Pashine, A.; Valiante, N.M.; Ulmer, J.B. Targeting the innate immune response with improved vaccine adjuvants. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, S63–S68.

- Colomer-Lluch, M.; Ruiz, A.; Moris, A.; Prado, J.G. Restriction factors: From intrinsic viral restriction to shaping cellular immunity against HIV-1. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2876.

- Gregorio, E.D.; Caproni, E.; Ulmer, J.B. Vaccine adjuvants: Mode of action. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 214.

- Ozata, D.M.; Gainetdinov, I.; Zoch, A.; O’Carroll, D.; Zamore, P.D. PIWI-interacting RNAs: Small RNAs with big functions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 89–108.

- Iwasaki, Y.W.; Siomi, M.C.; Siomi, H. PIWI-Interacting RNA: Its Biogenesis and Functions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015, 84, 405–433.

- An, W.; Han, J.S.; Wheelan, S.J.; Davis, E.S.; Coombes, C.E.; Ye, P.; Triplett, C.; Boeke, J.D. Active retrotransposition by a synthetic L1 element in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 18662–18667.

- Yeung, M.L.; Bennasser, Y.; Watashi, K.; Le, S.Y.; Houzet, L.; Jeang, K.T. Pyrosequencing of small non-coding RNAs in HIV-1 infected cells: Evidence for the processing of a viral-cellular double-stranded RNA hybrid. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 6575–6586.

- Yan, Z.; Hu, H.Y.; Jiang, X.; Maierhofer, V.; Neb, E.; He, L.; Hu, Y.; Hu, H.; Li, N.; Chen, W.; et al. Widespread expression of piRNA-like molecules in somatic tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 6596–6607.

- Siomi, M.C.; Sato, K.; Pezic, D.; Aravin, A.A. PIWI-interacting small RNAs: The vanguard of genome defence. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 246–258.

- Ernst, C.; Odom, D.T.; Kutter, C. The emergence of piRNAs against transposon invasion to preserve mammalian genome integrity. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1411.

- Czech, B.; Hannon, G.J. One Loop to Rule Them All: The Ping-Pong Cycle and piRNA-Guided Silencing. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 324–337.

- Tarlinton, R.E.; Sarker, N.; Fabijan, J.; Dottorini, T.; Woolford, L.; Meers, J.; Simmons, G.; Owen, H.; Seddon, J.M.; Hemmatzedah, F.; et al. Differential and defective expression of Koala Retrovirus reveal complexity of host and virus evolution. bioRxiv 2017, 211466.

- Gaj, T.; Gersbach, C.A.; Barbas, C.F., 3rd. ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 397–405.

- Yang, L.; Güell, M.; Niu, D.; George, H.; Lesha, E.; Grishin, D.; Aach, J.; Shrock, E.; Xu, W.; Poci, J.; et al. Genome-wide inactivation of porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERVs). Science 2015, 350, 1101–1104.

- Niu, D.; Wei, H.J.; Lin, L.; George, H.; Wang, T.; Lee, I.H.; Zhao, H.Y.; Wang, Y.; Kan, Y.; Shrock, E.; et al. Inactivation of porcine endogenous retrovirus in pigs using CRISPR-Cas9. Science 2017, 357, 1303–1307.

- Yue, Y.; Xu, W.; Kan, Y.; Zhao, H.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Song, X.; Wu, J.; Xiong, J.; Goswami, D.; Yang, M.; et al. Extensive germline genome engineering in pigs. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 5, 134–143.

- Tarlinton, R.E.; Fabijan, J.; Hemmatzadeh, F.; Meers, J.; Owen, H.; Sarker, N.; Seddon, J.M.; Simmons, G.; Speight, N.; Trott, D.J.; et al. Transcriptomic and genomic variants between koala populations reveals underlying genetic components to disorders in a bottlenecked population. Conserv. Genet. 2021.