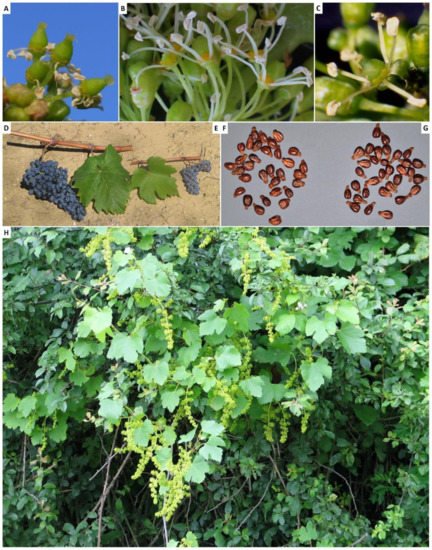

The grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.), besides being one of the most extensively cultivated fruit trees in the world, is also a fascinating subject for evolutionary studies. The domestication process started in the Near East and the varieties obtained were successively spread and cultivated in different areas. Whether the domestication occurred only once, or whether successive domestication events occurred independently, is a highly debated mystery. Moreover, introgression events, breeding and intense trade in the Mediterranean basin have followed, in the last thousands of years, obfuscating the genetic relationships. Although a succession of genomic studies has been carried out to explore grapevine origin and different evolution models are proposed, an overview of the topic remains pending.

- Vitis

- origin

- domestication

- grapes

- grapevine

- Viticulture

Introduction

The Domestication of the Grapevine in the Near East

Whether the grapevine was domesticated only once, or whether some varieties were domesticated independently, is a mystery hotly debated and different scenarios are proposed. The main hypothesis defined as the “Noah hypothesis”, so named in honour of the biblical patriarch who planted the first vineyard on Mount Ararat after the flood, proposes that grapevine domestication processes took place in a well-defined restricted area (Single-origin model). In addition, a multiple-origin hypothesis that provides for the foundation of independent lineages originating from wild progenitors spread some place along the entire distribution range has been proposed (Multi-origin model).

Genetic relationships between wild and domesticated forms can be traced by molecular analysis and several markers are widely used to show the genetic structure and domestication history of crops. One of the modern challenges in plant science is to improve the access to and use of genetic variability hidden in the genomes. In the genomic era, efficient genotyping tools should be able to cover a large part of the genome. In the last years, several authors have observed a reduction of genetic variability, confirming that the grapevine has suffered from a weak domestication bottleneck in the Near East followed by diffusion towards Europe [7,8,9]. However, studies carried out on germplasm resources collected in the Caucasus have shown an unexpected diversity and richness [49] raising some doubts about the correct geographic place of the main domestication area.

Plastid microsatellites have been used to explore the haplotype diversity from grapevine cultivars distributed from the Near East to the Mediterranean basin. Even though conclusions cannot be drawn about the domestication area from the results, the existence in the past of an intensive varietal exchange of germplasm and propagation throughout Europe have been evidenced [10]. On the other hand, Arroyo-García et al. [11], have examined the haplotype relationships under a network model in a large sampling of wild and domesticated accessions. The results supported the existence of at least two centres of domestication, one in the Near East and another in the Western Mediterranean region, confirming the involvement of several founders recruited throughout a prolonged time period. However, further studies are needed to understand the contributions made by the wild populations located in the Italian and Iberian Peninsulas, France and Greece (including the main islands of the Mediterranean basin) and to understand whether these locations have had a role of secondary domestication or were diversification centres.

Conclusions

References

- International Organisation of Vine and Wine. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/en/ (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- This, P.; Lacombe, T.; Thomas, M.R. Historical origins and genetic diversity of wine grapes. Trends Genet. 2006, 22, 511–519.

- Caporali, E.; Spada, A.; Marziani, G.; Failla, O.; Scienza, A. The arrest of development of abortive reproductive organs in the unisexual flower of Vitis vinifera ssp. silvestris. Sex. Plant Reprod. 2003, 15, 291–300.

- Naqinezhad, A.; Ramezani, E.; Djamali, M.; Schnitzler, A.; Arnold, C. Wild grapevine (Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris) in the Hyrcanian relict forests of northern Iran: An overview of current taxonomy, ecology and palaeorecords. J. For. Res. 2018, 29, 1757–1768.

- Ekhvaia, J.; Akhalkatsi, M. Morphological variation and relationships of Georgian populations of Vitis vinifera L. subsp. sylvestris (C.C. Gmel.) Hegi. Flora Morphol. Distrib. Funct. Ecol. Plants 2010, 205, 608–617.

- Zohary, D.; Hopf, M.; Weiss, E. Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin; Zohary, D., Hopf, M., Weiss, E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; ISBN 9780199549061.

- Myles, S.; Boyko, A.R.; Owens, C.L.; Brown, P.J.; Grassi, F.; Aradhya, M.K.; Prins, B.; Reynolds, A.; Chia, J.-M.; Ware, D.; et al. Genetic structure and domestication history of the grape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 3530–3535.

- De Lorenzis, G.; Mercati, F.; Bergamini, C.; Cardone, M.F.; Lupini, A.; Mauceri, A.; Caputo, A.R.; Abbate, L.; Barbagallo, M.G.; Antonacci, D.; et al. SNP genotyping elucidates the genetic diversity of Magna Graecia grapevine germplasm and its historical origin and dissemination. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacilieri, R.; Lacombe, T.; Le Cunff, L.; Di Vecchi-Staraz, M.; Laucou, V.; Genna, B.; Péros, J.-P.; This, P.; Boursiquot, J.-M. Genetic structure in cultivated grapevines is linked to geography and human selection. BMC Plant Biol. 2013, 13, 25.

- Imazio, S.; Labra, M.; Grassi, F.; Scienza, A.; Failla, O. Chloroplast microsatellites to investigate the origin of grapevine. Genet. Resour. Crops Evol. 2006, 53, 1003–1011.

- Arroyo-García, R.; Ruiz-García, L.; Bolling, L.; Ocete, R.; López, M.A.; Arnold, C.; Ergul, A.; Söylemezoğlu, G.; Uzun, H.I.; Cabello, F.; et al. Multiple origins of cultivated grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. ssp. sativa) based on chloroplast DNA polymorphisms . Mol. Ecol. 2006, 15, 3707–3714.

- Zecca, G.; Labra, M.; Grassi, F. Untangling the evolution of American wild grapes: Admixed species and how to find them. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1814.

- Zecca, G.; De Mattia, F.; Lovicu, G.; Labra, M.; Sala, F.; Grassi, F. Wild grapevine: Silvestris, hybrids or cultivars that escaped from vineyards? Molecular evidence in Sardinia. Plant Biol. 2010, 12, 558–562.

- D’Onofrio, C. Introgression among cultivated and wild grapevine in Tuscany. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 202.

- Di Vecchi-Staraz, M.; Laucou, V.; Bruno, G.; Lacombe, T.; Gerber, S.; Bourse, T.; Boselli, M.; This, P. Low level of pollen-mediated gene flow from cultivated to wild grapevine: Consequences for the evolution of the endangered subspecies Vitis vinifera L. subsp. silvestris. J. Hered. 2009, 100, 66–75.

- Ocete Rubio, R.; Ocete Rubio, E.; Ocete Pérez, C.; Ángeles Pérez Izquierdo, M.; Rustioni, L.; Failla, O.; Chipashvili, R.; Maghradze, D. Ecological and sanitary characteristics of the Eurasian wild grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. ssp. sylvestris (Gmelin) Hegi) in Georgia (Caucasian region). Plant Genet. Resour. 2012, 10, 155–162.

- Grassi, F.; Imazio, S.; Failla, O.; Scienza, A.; Ocete Rubio, R.; Lopez, M.A.; Sala, F.; Labra, M. Genetic Isolation and diffusion of wld grapevine Italian and Spanish populations as estimated by nuclear and chloroplast SSR Analysis. Plant Biol. 2003, 5, 608–614.

- Terral, J.F.; Tabard, E.; Bouby, L.; Ivorra, S.; Pastor, T.; Figueiral, I.; Picq, S.; Chevance, J.B.; Jung, C.; Fabre, L.; et al. Evolution and history of grapevine (Vitis vinifera) under domestication: New morphometric perspectives to understand seed domestication syndrome and reveal origins of ancient European cultivars. Ann. Bot. 2010, 105, 443–455.

- Pagnoux, C.; Bouby, L.; Ivorra, S.; Petit, C.; Valamoti, S.-M.; Pastor, T.; Picq, S.; Terral, J.-F. Inferring the agrobiodiversity of Vitis vinifera L. (grapevine) in ancient Greece by comparative shape analysis of archaeological and modern seeds. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 2015, 24, 75–84.

- Wales, N.; Madrigal, J.R.; Cappellini, E.; Baez, A.C.; Castruita, J.A.S.; Romero-Navarro, J.A.; Carøe, C.; Ávila-Arcos, M.C.; Peñaloza, F.; Moreno-Mayar, J.V.; et al. The limits and potential of paleogenomic techniques for reconstructing grapevine domestication. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2016, 72, 57–70.

- Zhou, Y.; Minio, A.; Massonnet, M.; Solares, E.; Lv, Y.; Beridze, T.; Cantu, D.; Gaut, B.S. The population genetics of structural variants in grapevine domestication. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 965–979.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22094518