The demand for gas detection is increasing nowadays. However, its fast detection at room temperature (RT) is a major challenge. Graphene is found to be the most promising sensing material for RT detection, owing to its high surface area and electrical conductivity. The high edge functionalized chemically synthesized graphene derivatives thin films are promising candidates to achieve a fast gas sensing response at room temperature. The high amount of edge functional groups is prominent for the sorption of analyte gas/vapor molecules.

- graphene

- gas sensor

- functionalization

- oxygen functional groups

- response time

- recovery time

- room temperature sensing

Introduction

The need for high-quality gas sensor development is increasing for the detection of various environmental pollutants that have an adverse effect on humans, animals, and plants. Over the past few years, atmospheric pollutants are being produced as a continuous growth of industries, deforestation, and burning of fossil fuels. Furthermore, CO2 is one of the main causes of global warming and climate change. Moreover, CO2 gas is also attracting the serious attention of researchers in various fields such as CO2 storage, capture, and utilization. The level of CO2 in the atmosphere is unacceptably increasing day by day [1].

Novel materials, such as amino-ZnO, Ru@WS2, vanadium oxide, nanodiamonds, Al/maPsi/n-Si/Al, and carbon nanotube, have been recently explored for CO2 gas sensing at room temperature. However, the sensing thin films of these materials require a mild thermal treatment before sensing at room temperature. In addition, the gas sensors based on these materials have realized the longer recovery time (2–6 min). Besides these materials, graphene and its hybrids [2][3][4] are emerging as the promising contender for CO2 detection at room temperature due to their extraordinary properties such as high surface to volume ratio, high conductivity, and high chemical reactivity [5][6]. Owing to its very high volume–exposure ratio, a small amount of the graphene-based material enriched with the high surface area can provide ample active sites for high adsorption of the analyte gas molecules [7][8]. The derivative of graphene—reduced graphene oxide (rGO)—has also attracted much research attention in various application including catalysts, bio/gas sensors, electronic devices, and transparent electrodes, due to its facile implementation and outstanding properties such as hydrophilic nature, low-cost production, tunable optical band gap, and large surface area with high catalytic reactivity.

Various methods have been investigated to reduce the GO for CO2 gas detection at room temperature, such as thermal reduction, exfoliation, spray pyrolysis technique, and the hydrogen plasma technique. However, these methods need a high temperature for the reduction of GO and its mass production is limited. On the contrary, the chemically reduced graphene requires low temperature for the reduction of GO and it is suitable for mass production [9]. Moreover, the chemical reduction of GO offers the ease of surface modification and the functionalization of graphene oxide. The GO contains several oxygen functional groups (OFGs), such as the carboxyls, carbonyls, epoxides, and hydroxyls, which are covalently or non-covalently bonded in the form of hydrogen bonds and pi-pi bonds on its edge and basal plane[10]. The OFGs at the rGO surface are the dominant factor for analyte gas molecule adsorption at room temperature. These OFGs cause disruption to the pi–pi network that manifests as defects in the graphene sheet [11]. The pi–pi conjugate network of sp2 hybridized carbon structure and the sheet conductivity are restored when the OFGs are released from the GO sheet during the reduction process [12]. The OFGs can be efficiently tailored by the chemical reduction method. During the reduction of GO, the key interests are (i) the fraction of OFGs are involved during the reduction process, (ii) how many functional groups are leaving the surface, (iii) how many functional groups remain at the edge plane, and basal plane, and (iv) the formation of defects on the edge or basal plane when the OFGs leave the GO surface. Although both edge and basal plane OFGs take part in the molecule adsorption, the edge plane OFGs dominates. The basal plane OFGs (hydroxyl) work as the surface trap sites for the charge carriers (electrons and holes) [13]. Due to the basal plane trap sites, high-temperature annealing is required to achieve the desorption of gas molecules. For the fast CO2 gas detection at room temperature, the edge functionalities are favorable as compared to the basal plane functionalities. The amount of OFGs at the edge plane and basal plane can be modified by changing the synthesis parameters such as synthesis duration, temperature, the type, and concentration of the reducing agent [14].

Graphene Derivatives-

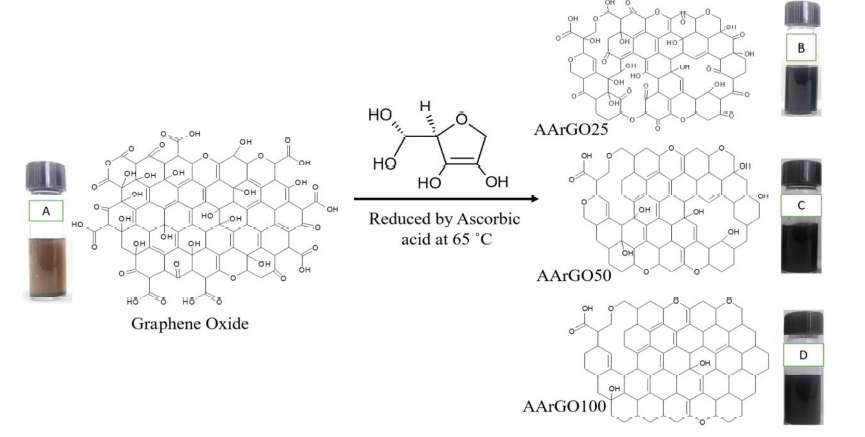

Graphene derivatives like reduced graphene oxide (rGO) are chemically synthesized by using various reducing agents such as ascorbic acid and hydrazine. Figure 1 depicts a representation of the reduction process of GO using Ascorbic acid (AA) and the formation of AArGO materials with different amounts of OFGs. In graphene oxide, the OFGs are attached between the graphene layers, at the edges, and the surface of graphene. When GO is chemically reduced, the AA interacts with these OFGs. AA reduces mainly the basal plane functional groups such as hydroxyls and epoxides [14]. The OFGs such as hydroxyls and epoxides are mainly fastened at the basal plane whereas the other OFGs such as carboxyls and carbonyls are dominant functional groups at the edges[15]. The existence of the carbonyl and carboxyl edge functionalities assures the presence of more active sites for the sorption of analyte gas like CO2. However, in the case of GO (before the reduction), these OFGs do not behave as active sites because these covalently bonded OFGs are hard to detach from the GO surface at room temperature until an external excitation like thermal treatment is provided. Furthermore, these edge functionalities majorly contribute to the high stability and low tendency of agglomerations in the AArGO[16]. The dispersion of edge functionalized graphene is better than basal plane functionalized graphene. Carbonyl and carboxyl OFGs contribute to better dispersion properties of the material[14].

Figure 1 Representation of oxygen functional groups (OFGs) after the reduction of graphene oxide using ascorbic acid. Graphene oxide (A), AArGO25 (B), AArGO50 (C), AArGO100 (D).

FTIR Analysis

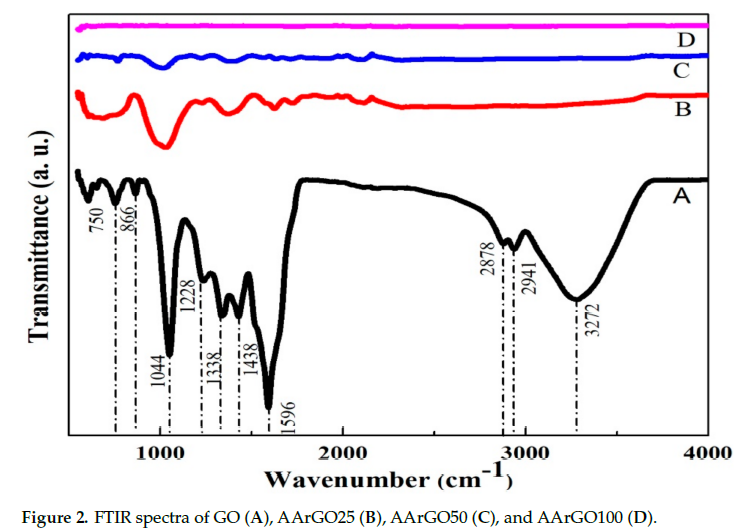

The structural properties of GO and rGO samples have been studied by using FTIR spectroscopy. Figure 2 shows the FTIR spectra of GO (A), AArGO25 (B), AArGO50 (C), and AArGO100 (D). The GO spectrum shows a broad absorption band centered at 3182 cm-1 attributed to the –OH stretching vibration and indicating the presence of –OH and –COOH functional groups within the structure. This band is related to the absorbed and inhibited water molecule to atmospheric moisture. The peaks at 1724, and 1620 cm-1 were observed suggesting the vibrations of C=O stretching, and C=C alkene group stretching. Some other peaks at 1225 and 1044 cm-1 were also observed indicating the C–O stretching of epoxy groups and C–O stretching vibration of an alkoxy group, respectively. In the AArGO spectra, it was noticed that the peak intensity of most of the oxygens functional group (OFGs) was found to be decreased that indicates the successful reduction of graphene oxide by AA reducing agent. It was also observed that the peaks due to the hydroxyl group were absent ~3182 cm-1 in all the AArGO samples but the emergence of the absorption peak at ~1580 cm-1 (the aromatic structure) indicates the successful deoxygenation of the rGOs by AA[17].

Surface Morphology

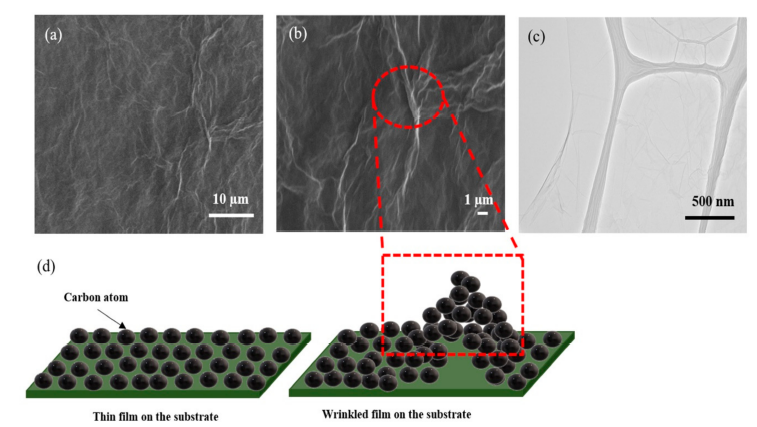

To investigate the morphology of the rGO sample, the SEM and TEM characterizations were carried out. The morphology of AArGO25 investigated using SEM and TEM is shown in Figure 3. The AArGO25 was found to have a pleated surface as shown in the SEM image (Figure 3a). Several corrugations and wrinkles were also observed on the high magnification SEM image of the surface as presented in Figure 3b. Figure 3c illustrates the AArGO25 surface on the holey copper grid during TEM imaging. The surface was found to be a continuous thin layer. Some folds and wrinkles were also identified on edge of the surface. These corrugations on the AArGO25 surface can modify its electronic structure, mechanical, optical, and chemical properties[5]. The formation and the effect of wrinkles on the AArGO surface are illustrated in Figure 3d. The wrinkles are formed due to the interaction between substrate and graphene mainly caused by the difference between Young’s moduli of substrate and graphene [18].

Figure 3 SEM of AArGO25 at (a) lower magnification and, (b) higher magnification, (c) TEM image, (d) Schematic illustration of wrinkles on AArGO25 surface.

XPS Analysis

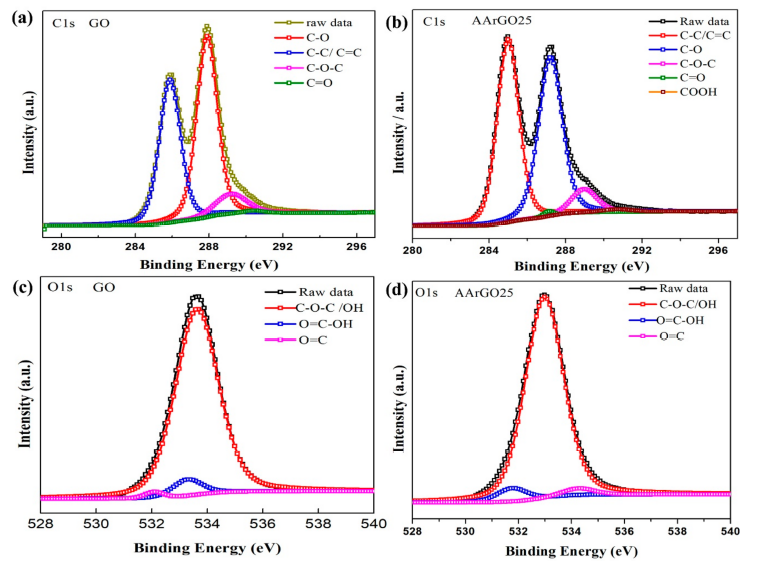

The chemical composition and elemental analysis for the GO and AArGO25 were investigated using XPS-C1s spectra as illustrated in Figure 4. After deconvolution, the C1s spectrum of GO showed four major peaks that correspond to C–C/C=C (285.8 eV, ~27.9%) in aromatic rings, C–O epoxy and alkoxy (287.9 eV, ~34.3%), C–O–C (289.21 eV, ~5.75%), and C=O double bond (290.4 eV, ~0.53%) as depicted in Figure 4a. The reduction of GO mainly affected the C–C/C=C bond and the intensity of C–C/C=C peak was dramatically increased from 27.9% (GO) to 33.35% in AArGO25 as illustrated in Figure 4b, indicating a high removal rate of the epoxide and hydroxyl (C–O) groups and abundance of edge functionalities. These changes in OFGs lead to the enhanced dispersion stability of AArGO25 material [16] [46]. A similar observation on the reduction of hydroxides was found during the FTIR analysis of AArGO25. The peak intensity of the AArGO25 carbonyl group (C=O) was found to be higher than that of GO, attributing to a higher number of carbonyl elements of the AArGO25 material. These carbonyl OFGs form the defective surface of AArGO25. These defects are the main active sites for the adsorption of the CO2 gas molecules. In addition, the C/O ratio was also slightly increased from 2.17 (GO) to 2.44 (AArGO25), reflecting the reduction of GO with an abundance of OFGs. Additionally, FWHM (full width at half maximum) value was found to be 1.52 and 1.33 for GO and AArGO25, respectively. The smaller FWHM value for AArGO25 suggests its good electrical conductivity with a large number of holes [14]. These holes are formed by the breaking of C–C bonds in the basal plane and interactions between the neighboring hydroxyl and epoxy groups during the reduction process [5][19].

Figure 5. C1s and O1s XPS spectra of GO and AArGO25 thin films. C1s spectra of (a) GO and (b) AArGO25. O1s spectra of (c) GO and (d) AArGO25.

Moreover, the analysis of the high-resolution O1s spectra was performed to get considerable information on sorption. The O1s spectra of GO and AArGO25 are shown in Figure 4c,d, respectively. The O1s spectrum of GO decomposed in three peaks associated with C–O (~533.6 eV), C=O (~533.0 eV), and O–C=OH (~533.2 eV) as shown in Figure 4c, whereas these three major peaks for AArGO25 were found to be ~534.9 eV, ~534. 2 eV, and ~531.7 eV, respectively. The observed significant reduction in the binding energy of the C–O group for AArGO25 is found to be agreed with the trend observed by Chen et al. [40], Rabchinskii et al. [44]. Furthermore, the amount of oxygen in AArGO25 was reduced from 31.47% (GO) to 29.08%, indicating the reduction of GO.

The functionalized graphene has high potential in the field of gas/vapor sensing, biosensing, supercapacitors, water treatment, CO2 utilization, CO2 capture, and sequestration. By changing the surface properties of chemically reduced graphene is a promising technology for future applications.

The entry is from 10.3390/nano11030623

References

- Kenichi Azuma; Naoki Kagi; U. Yanagi; Haruki Osawa; Effects of low-level inhalation exposure to carbon dioxide in indoor environments: A short review on human health and psychomotor performance. Environment International 2018, 121, 51-56, 10.1016/j.envint.2018.08.059.

- Shrouk E. Zaki; Mohamed A. Basyooni; Mohamed Shaban; Mohamed Rabia; Yasin Ramazan Eker; Gamal F. Attia; Mucahit Yilmaz; Ashour M. Ahmed; Role of oxygen vacancies in vanadium oxide and oxygen functional groups in graphene oxide for room temperature CO2 gas sensors. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2019, 294, 17-24, 10.1016/j.sna.2019.04.037.

- Pradeep Kumar; Chun Hong Kang; Zainal Arif Burhanudin; M. Shuaib M. Saheed; M. I. Irshad; Norani Muti Mohamed; Graphene-based hybrid thin films as transparent conductive electrode for optoelectronic devices. 2016 IEEE International Conference on Semiconductor Electronics (ICSE) 2016, , , 10.1109/smelec.2016.7573630.

- Pradeep Kumar; Kai Lin Woon; Wah Seng Wong; Mohamed Shuaib Mohamed Saheed; Zainal Arif Burhanudin; Hybrid film of single-layer graphene and carbon nanotube as transparent conductive electrode for organic light emitting diode. Synthetic Metals 2019, 257, 116186, 10.1016/j.synthmet.2019.116186.

- Yiqian Jin; Yiteng Zheng; Simon G. Podkolzin; Woo Lee; Band gap of reduced graphene oxide tuned by controlling functional groups. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2020, 8, 4885-4894, 10.1039/c9tc07063j.

- Monika Gupta; Nurul Athirah; Huzein Fahmi Hawari; Graphene derivative coated QCM-based gas sensor for volatile organic compound (VOC) detection at room temperature. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science 2020, 18, 1279-1286, 10.11591/ijeecs.v18.i3.pp1279-1286.

- Li Guo; Ya-Wei Hao; Pei-Long Li; Jiang-Feng Song; Rui-Zhu Yang; Xiu-Yan Fu; Sheng-Yi Xie; Jing Zhao; Yong-Lai Zhang; Improved NO2 Gas Sensing Properties of Graphene Oxide Reduced by Two-beam-laser Interference. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 1-7, 10.1038/s41598-018-23091-1.

- Pradeep Kumar; Ling Hoe Chee; Chun Hong Kang; Zainal Arif Burhanudin; Mohamed Shuaib B M Saheed; Au-decorated graphene-carbon nanotube hybrid thin film for sub-100 ohm/sq transparent conductive electrodes. TENCON 2017 - 2017 IEEE Region 10 Conference 2017, , , 10.1109/tencon.2017.8228125.

- Dandan Hou; Qinfu Liu; Hongfei Cheng; Kuo Li; Graphene Synthesis via Chemical Reduction of Graphene Oxide Using Lemon Extract. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 2017, 17, 6518-6523, 10.1166/jnn.2017.14426.

- Hongmei Yang; Jiu-Sheng Li; Xiangqiong Zeng; Correlation between Molecular Structure and Interfacial Properties of Edge or Basal Plane Modified Graphene Oxide. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2018, 1, 2763-2773, 10.1021/acsanm.8b00405.

- Cooper, D.R.; D’Anjou, B.; Ghattamaneni, N.; Harack, B.; Hilke, M.; Horth, A.; Majlis, N.; Massicotte, M.; Vandsburger, L.; Whiteway, E.; et al. Experimental Review of Graphene. ISRN Condens. Matter Phys 2012, 501686, -, .

- A Bhaumik; A Haque; Mfn Taufique; Priyanka Karnati; R Patel; M Nath; K Ghosh; Reduced Graphene Oxide Thin Films with Very Large Charge Carrier Mobility Using Pulsed Laser Deposition. Journal of Material Science & Engineering 2017, 6, 1-11, 10.4172/2169-0022.1000364.

- Haneef, H.F.; Zeidell, A.M.; Jurchescu, O.D.; Charge carrier traps in organic semiconductors: A review on the underlying physics and impact on electronic devices. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 759–787 2020, 8, 759-787, .

- Chiaying Chen; Yen-Chun Chen; Yu-Ting Hong; Ting-Wei Lee; Jing-Fang Huang; Facile fabrication of ascorbic acid reduced graphene oxide-modified electrodes toward electroanalytical determination of sulfamethoxazole in aqueous environments. Chemical Engineering Journal 2018, 352, 188-197, 10.1016/j.cej.2018.06.110.

- Susumu Yamamoto; Kaori Takeuchi; Yuji Hamamoto; Ro-Ya Liu; Yuichiro Shiozawa; Takanori Koitaya; Takashi Someya; Keiichiro Tashima; Hirokazu Fukidome; Kozo Mukai; et al. Enhancement of CO2 adsorption on oxygen-functionalized epitaxial graphene surface under near-ambient conditions. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2018, 20, 19532-19538, 10.1039/c8cp03251c.

- Chih-Jen Shih; Shangchao Lin; Richa Sharma; Michael S. Strano; Daniel Blankschtein; Understanding the pH-Dependent Behavior of Graphene Oxide Aqueous Solutions: A Comparative Experimental and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. Langmuir 2011, 28, 235-241, 10.1021/la203607w.

- Maxim K. Rabchinskii; Arthur T. Dideikin; Demid A. Kirilenko; Marina V. Baidakova; Vladimir V. Shnitov; Friedrich Roth; Sergei V. Konyakhin; Nadezhda A. Besedina; Sergei I. Pavlov; Roman A. Kuricyn; et al. Facile reduction of graphene oxide suspensions and films using glass wafers. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 1-11, 10.1038/s41598-018-32488-x.

- Won-Kyu Lee; Junmo Kang; Kan-Sheng Chen; Clifford J. Engel; Woo-Bin Jung; Dongjoon Rhee; Mark C. Hersam; Teri W. Odom; Multiscale, Hierarchical Patterning of Graphene by Conformal Wrinkling. Nano Letters 2016, 16, 7121-7127, 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b03415.

- A. Bagri; R. Grantab; N. V. Medhekar; V. B. Shenoy; Stability and Formation Mechanisms of Carbonyl- and Hydroxyl-Decorated Holes in Graphene Oxide. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2010, 114, 12053-12061, 10.1021/jp908801c.