The nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans has been used extensively to enhance our understanding of the human neuromuscular disorder Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD). This review provides an in depth insight into this body of work.

- DMD

- C. elegans

- dystrophin

- muscle

1. Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an inherited X-linked recessive disorder characterised by progressive muscle degeneration and weakness, with onset in early childhood [1]. DMD is the most common muscular dystrophy in children, with an incident rate of approximately 1 in 3500 live male births [2]. DMD is caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene, which is the largest known human gene and encodes a set of dystrophin proteins, the major one being a 427 kDa protein. It is primarily located in muscles, but small amounts are also present in neuronal cells [3]. Despite our extensive knowledge of dystrophin and its associated dystrophin glycoprotein complex (DGC), a cure remains elusive.

There are over 60 animal models for DMD that are currently available including the dystrophic mdx mouse [4], dystrophin deficient rats [5,6] and the golden retriever DMD model [7]. Although these models are invaluable, they require a long gestation period, a significant amount of space and care, and the following of strict ethical guidelines. A model to study human diseases that bypasses the aforementioned limitations is Caenorhabditis elegans. Studying muscular dystrophy in C. elegans results in more rapid and more cost-effective experiments; they are simple to feed and maintain throughout their short lifespan (approximately 3 weeks). The C. elegans DMD model was first reported by Segalat and colleagues in 1998 and has since been applied in a number of disease focused studies [8,9]. A comparison of some of the different animal models that have been used to study DMD can be found in Table 1.

| Model Type | Benefits | Similarities to DMD in Humans | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. elegans | Easy and cheap to maintain, short lifespan, high throughput experiments possible. Similar muscle structure and has orthologues for most human DGC proteins [10]. | Display movement and strength decline [11], altered gait [12] and shortened lifespan [13]. | Have a very simple body plan and nonconventional circulatory system [14]. Are unable to regenerate muscle as they lack satellite cells and do not have a conventional inflammatory system [15]. |

| Zebrafish | Easy to house and care for, high throughput experiments possible. High skeletal muscle content and expresses orthologues of most human DGC proteins [16]. | Changes in gait and lower activity [17]. | Missing several mammalian organs, are ectothermic and are influenced heavily by their environment. |

| Mdx mouse | One of the easier mammalian models to house and care for with a relatively short lifespan. High genetic similarity to humans including a DGC [4]. | Genetic and biochemical homologue of disease in humans. Displays ECG abnormalities and cardiomyopathy [18]. | Minimal clinical symptoms (no loss of ambulation and muscle weakness is not displayed until ~15 months) and lifespan is not majorly reduced [19]. |

| Dystrophin deficient rats | A convenient size as they are larger than mice allowing for studies with high statistical power but still relatively easy to house and care for. High genetic similarity including a DGC [5]. | Muscles showed severe fibrosis, muscle weakness and reduced activity [5,6]. | Not a well-established model and characterisation is still ongoing. |

| Golden retriever | Higher genetic similarity to humans compared to other mammalian models. Case reports showing that DMD occurs naturally in these animals as well. | Extensive homology in pathogenesis. Pathogenesis manifests in utero and extensive muscle necrosis can be seen and is progressive. They also have a shortened life span frequently dying from cardiac and respiratory failure [7]. | Expensive to maintain, not easily genetically manipulable and many ethical concerns. |

In C. elegans, the homologue for mammalian dystrophin is dys-1, which encodes for a dystrophin-like protein called DYS-1. In C. elegans there are two known isoforms of DYS-1: DYS-1A and DYS-1B. Whilst DYS-1A is almost analogous to human dystrophin, DYS-1B only corresponds to the last 237 amino acids of isoform A [15]. DYS-1 has been shown to be expressed in the body wall, head, pharyngeal and vulva muscles [20].

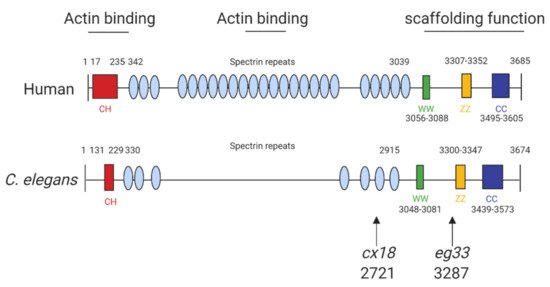

The structure of human dystrophin and C. elegans share extensive sequence similarities (Figure 1) and introducing mutations into C. elegans dys-1 gives clinically relevant phenotypes (Table 2). The main models used are dys-1(cx18), dys-1(cx18;hlh-1) and dys-1(eg33), and the position of these mutations can be seen in Figure 1. To further support the usefulness of this model, the introduction of human dystrophin cDNA is able to rescue these phenotypes [13].

Figure 1. Structure of human and C. elegans dystrophin proteins. The structures of human dystrophin and C. elegans DYS-1. The size of human and C. elegans dystrophin is almost equivalent. They also share similarities in key motifs: CC, coiled coil domain; CH, calponin homology domain (“actin-binding” domain); WW, domain with two conserved W residue; ZZ, zinc finger domain. The arrows indicate the amino acid positions of the mutation sites for the commonly used mutants: cx18 and eg33 alleles, which are both nonsense mutations. Adapted from Oh and Kim (2013) [13] and Gieseler et al. (2017) [15]. Created with biorender.com.

| Class of Phenotype | dys-1(cx18) | dys-1(cx18;hlh-1) | dys-1(eg33) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Locomotion | Exaggerated body bends, hyperactive, hypercontracted, overbent, swimming defective and burrowing defective [11,20,21,22,23]. | Exaggerated body bends, hyperactive, hypercontracted, overbent and swimming defective [24,25]. | Exaggerated body bends, hyperactive, hypercontracted, overbent, swimming defective and burrowing defective [11,12,22,23,26]. |

| Muscle structure | Very little muscle degeneration [20]. | Severe muscle degeneration [24]. | Severe muscle degeneration [13]. |

| Response to neuromuscular agents | Aldicarb hypersensitive, levamisole resistant [11,20]. | ND | Levamisole resistant [11]. |

| Mitochondria structure and function | Minor fragmentation of the mitochondria network, moderate depolarisation of mitochondrial membrane, no change in basal oxygen consumption rate [11]. | Severe fragmentation of the mitochondria network [27]. | Severe fragmentation of the mitochondria network, severe depolarisation of the mitochondrial membrane, elevated basal oxygen consumption rate [11,12]. |

| Life span | Shortened life span [13,28]. | ND | Shortened life span [12,13,28]. |

| Egg laying | No defect noted [20]. | Egg laying defect [24]. | ND |

| Strength | Not detectably weaker than WT [11]. | ND | Significant weakness detected compared to WT [11,12]. |

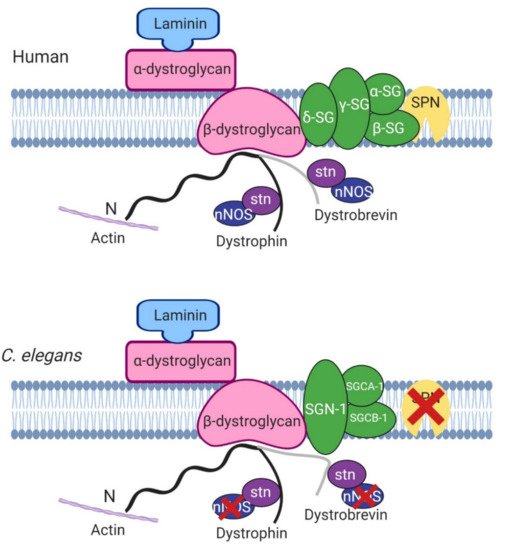

One of the roles of dystrophin is to link the cytoskeleton, the sarcolemma and the extracellular matrix (ECM) by binding cortical F-actin via its N-terminus and DGC proteins via its C-terminus. The DGC is a monomeric complex that is composed of at least 10 different proteins including dystroglycans, sarcoglycans, sarcospan, dystrobrevins and syntrophin (reviewed by Blake et al. 2015 [3]). There is significant evidence of conserved homologues for the other components of the DGC in C. elegans, further highlighting the usefulness of C. elegans in the study of DMD (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Basic structure of human and C. elegans dystrophin glycoprotein complex. Most of the proteins in the mammalian model are found in C. elegans apart from sarcospan (SPN) and nitric oxide synthase (nNOS). SG, sarcoglycans, stn, syntrophin. Adapted from Grisoni et al. (2002) [10]. Created with biorender.com.

Despite the proven usefulness of the C. elegans model, it also has its limitations. C. elegans have a very simple body plan, they have similar protein networks to humans (but the exact nature of the interactions is different due to the varying levels of homology between genes), they lack satellite cells and lack a conventional inflammatory system [15,29].

2. Phenotypes Observed in C. elegans DMD Mutants

2.1. The dys-1 Single Mutant

The dystrophin homologue in C. elegans, dys-1, was identified over 20 years ago. Loss-of-function mutations of the dys-1 gene (dys-1(cx18/cx26/cx35/cx40/ad538)) made animals hyperactive and slightly hypercontracted. Additionally, the dys-1 mutants were found to be hypersensitive to acetylcholine and to the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor aldicarb, suggesting that dys-1 mutations affect cholinergic transmission. Interestingly, these mutants appeared to have normal muscle cells. Moving forwards the worm mutant dys-1(cx18), which has a nonsense mutation at amino acid 2721 (Figure 1), was predominantly used as its phenotypes could not be distinguished from carboxy-terminal deletions of the gene [20].

2.2. Enhancing the Phenotype of dys-1 Mutants

In patients with DMD, severe muscle degeneration is a well-recognised phenotype. As mutations in dys-1 did not result in muscle degeneration as would be expected, it was hypothesised that this was likely due to the short lifespan of the animals, as this phenotype can take a long time to become present in mammals [20]. The mdx mouse model, akin to the dys-1 single mutant, has a mild phenotype and thus is not the best model for human DMD. To improve the mouse model, double knockout mice were generated lacking dystrophin and MyoD which display severe muscle degeneration [32], and it was thought combining a mutation in hlh-1 (C. elegans homologue of MyoD) with dys-1 would give a time-dependent muscle degeneration that was lacking in the original single mutant. This led to the generation of the dys-1(cx18);hlh-1(cc561ts) mutant [24]. This double mutant had a similar phenotype to its predecessor but in addition it had severe muscle degeneration and an egg laying defect [24]. This double mutant has been used widely; however, the lack of understanding of the mechanism of these enhanced muscular degeneration effects may impact upon its translational importance.

2.3. Novel Mutation in dys-1

More recently, a newer mutation has been discovered which has a nonsense mutation at position 3287 (dys-1(eg33)). It is apparent that this model may be the most clinically relevant, as, unlike prior models carrying mutations in dys-1, this mutant shows muscle degeneration without the need for a sensitised background [13]. Furthermore, it has been shown to have similar locomotory defects to the previous two models but with increased severity. Various aspects of the dys-1(eg33) swimming environment have been assessed using the C. elegans Swim Test (CeleST), and these animals were deficient in almost all swimming measures [12,26]. To support that dys-1(eg33) is a more clinically relevant model, a recent study compared dys-1(eg33) and dys-1(cx18) [11]. dys-1(eg33) was found to be weaker, to exhibit a more severe decline in locomotion and have severe mitochondrial fragmentation compared to dys-1(cx18) and wild-type (WT) animals [11,12]. These animals were also shown recently to have altered pharyngeal pumping demonstrating a loss of calcium homeostasis [12]. Pharyngeal pumping has been proposed as a potential model for the heart in C. elegans as both are made of striated muscle, contract rhythmically and both are controlled by evolutionarily conserved genes [33]. However, it remains unclear how useful a model worm pharyngeal muscle is for cardiac dysfunction but a decline in pumping in the DMD model raises interesting possibilities [12]. Table 2 shows all known phenotypes associated with each of the models discussed.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22094891