Regenerative medicine is becoming a rapidly evolving technique in today’s biomedical progress scenario. Scientists around the world suggest the use of naturally synthesized biomaterials to repair and heal damaged cells. Hydroxyapatite (HAp) has the potential to replace drugs in biomedical engineering and regenerative drugs. HAp is easily biodegradable, biocompatible, and correlated with macromolecules, which facilitates their incorporation into inorganic materials.

- collagen

- hydroxyapatite

- drugs

- bioactive components

- metals

- nanoparticles

- regenerative medicine

- tissue engineering

1. Introduction

Tissue engineering is a modern scientific discipline concerning chemical, biological, and engineering principles that tries to use various methods to regenerate tissues [1][2]. It applies natural science and engineering principles and their innovations to such damaged tissues through the development of biological substitutes or through tissue reconstruction [3][4]. To revitalize, maintain, or enhance tissue function, tissue engineering helps to understand the structure and function of normal and pathological mammalian tissues [1][2][5][6]. The aim of tissue engineering is to develop new functional tissues and regenerate tissues in vitro or in vivo to treat diseases when surgery is necessary [7]. For many other disease states, tissue engineering remains a thriving area of research with potential new treatments [8]. It enables the regeneration of almost every tissue and organ in the human body [6]. General tissue-engineering strategies can be divided into three groups: (i) implantation of isolated cells into the body or cell replacement; (ii) delivery of tissue-inducing substances such as growth factor, which refers to proteins or polypeptides that can promote tissue growth; and (iii) placing cells in or on different matrices [6]. Tissue engineering is broadly divided into two types: (a) soft tissue engineering, which deals with skin, blood vessels, tendons/ligaments, cardiac lobe, nerves, and skeletal muscles; and (b) hard-tissue engineering, dealing with bones [9]. Bone-tissue engineering aims to induce ideal bone healing by using hybrid matrixes of osteoconductive and biodegradable biomaterials and osteoinductive growth factors [10][11]. In the area of bone-tissue engineering, the biomimetic scaffolds are designed to receive the artificial bone matrix and to support the adhesion of cells, followed by the process of new tissue formation [12]. Therefore, it is assumed that the scaffold is to imitate as much as possible the structure and the composition of natural tissues [13]. In recent years, scaffolds based on natural polymers, synthetic ones, or their adequate combinations are of great interest [14]. Of particular interest is a combination of synthetic polymers, which provide adequate mechanical strength and processability, with biopolymers, which ensure the cells have an appropriate environment for proliferation and the induction of tissue growth [15].

2. Hydroxyapatite

Hydroxyapatite (HAp) is a biologically active calcium phosphate ceramic with high ability to promote bone growth; however, its mechanical properties, such as low fracture toughness, poor tensile strength, and weak wear resistance, make it insufficient as a load-carrying material [16]. The literature refers to hydroxyapatite as HAP, HAp, HA, or OHAp [17][18][19]. Apatites are widespread minerals occurring in all types of rocks, mainly in Switzerland, Spain, Canada, Brazil, Australia, and Poland [18]. Biological apatites are found mainly in bones and teeth of vertebrates. They are also present in all pathologically calcified tissues, such as salivary, cerebral, kidney, bile, ureteral, and tartar stones. The apatite of which bones are made is referred to in the literature as “bone hydroxyapatite” [20][21][22]. The size of hydroxyapatite crystals in human bones depends on the age. Three characteristic ranges of average crystallite size can be identified: 188–215 nm—the childhood period under 6 years; 232–252 nm—the adolescent period of 6–19 years; and—252–283 nm—maturity [22][23]. Bone apatites are mainly acicular or lamellar crystals [24].

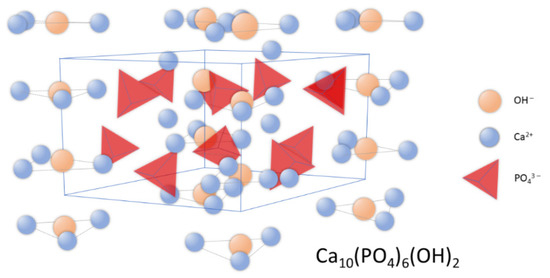

Synthetic apatites are a group of compounds that includes both stoichiometric hydroxyapatite, s-HAp, with a molar ratio of calcium to phosphorus equal to 1.667; as well as hydroxyapatite deviating from stoichiometry (ns-HAp). ns-HAp shows a very wide range of nonstoichiometry, as it can contain mainly water or HPO42−, H2PO4− ions, while OH− can be replaced by O2− [25][26][27][28]. Stoichiometric hydroxyapatite has a monoclinic structure, while HAp of mineralogical and biological origin has a hexagonal structure [29]. The unit cell parameters for the hexagonal system are: a = 9.41 Å, c = 6.88 Å, and the unit cell volume is 527.59 ų [18]; while for the monoclinic system, they are: a = 9.4215 Å, b = 2a, c = 6, 8815 Å [30]. Figure 1 shows the distribution of atoms in the hydroxyapatite crystal lattice.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of hydroxyapatite’s crystal structure.

In the unit cell, two crystallographically independent atoms of calcium, Ca (I) and Ca (II), can be observed. Ca (II) atoms form triangles that are located perpendicular to the c axis and mutually shifted by 60° to each other, while Ca (I) atoms are octahedrally surrounded by six oxygen atoms [31]. The structure of hydroxyapatite adopts a variety of isomorphic substitutions in both the cationic and anionic subnetworks without destroying the unit cell structure. The criteria determining the possibility of ion exchange are the similarity in dimensions and charges of the substituting and substituted ions [22][32][33]. Foreign elements are substituted into the structure of hydroxyapatite in an undefined amount, depending on the conditions of its formation [34].

In the structure of hydroxyapatite, the anions of PO43− can to some extent be exchanged for carbonate groups, and this is the so-called Type B carbonate hydroxyapatite, unlike type A, in which CO32− anions replace the hydroxyl groups [34][35]. Type A carbonate hydroxyapatite is obtained by high-temperature treatment >1000 °C. In naturally derived hydroxyapatite, carbonate anions can replace both the phosphate groups and the hydroxyl groups. Carbonate anions in biological hydroxyapatite are also adsorbed on its surface. Substitutions in the anionic subnetwork with other anions such as chlorine (0.13 wt %) or fluorine (0.03 wt %) are also possible. Calcium ions can be exchanged for magnesium (about 0.7% by weight); sodium (about 0.9% by weight); potassium (0.03%); and a number of trace elements (Sr, Pb, Zn, Cu, Fe) [36]. The presence of these elements affects the activity of enzymes related to the operation of bone cells. The incorporation of Mg2+ and CO32− ions causes a reduction in crystal size and an increase in solubility [37][38]. The effect of low crystallinity is high reactivity of bone apatites, which is reflected in bone-resorption processes. Foreign elements are incorporated in substitutions in amounts depending on the conditions of the formation of this structure; their presence also affects the stoichiometry (increasing the Ca/P molar ratio), crystallinity, and thermal and chemical stability of the compound [39].

There are molecular modeling methods that allow us to define the Hap structure. Bystrova et al. presented the first basic modeling and calculations for hydroxyapatite (HAP) nanostructures, as well as native, surface modified, charged, and with various defects (H and OH gaps, H internode) based on the first basic modeling [40].

There are many methods of obtaining hydroxyapatite powders, i.e., wet, dry, fluxing and sol-gel [25]. The mechanochemical method of obtaining hydroxyapatite is also known, but it has not found wide application [41]. Hydroxyapatite can also be obtained from natural materials such as corals, animal bones, and even fish bones [42][43][44][45]. The most widely used methods on an industrial and laboratory scale are wet methods. Particular methods allow the obtaining of materials with appropriate morphology, crystal structure, and Ca/P molar ratio, as well the incorporation of foreign cations or anions into the structure of hydroxyapatite [46][47].

Hydroxyapatite, due to its structural similarity to the mineral parts of natural bone, has been widely used in medicine and dentistry. The physicochemical and biological properties of hydroxyapatite make it possible to classify it as a bioactive material [48][49][50][51]. HAp has been applied in orthopedics, dentistry, maxillofacial surgery, ophthalmology, laryngology, and traumatology [25][32][52]. In medical practice, hydroxyapatite bioceramics are used in the forms of powder, granules, solid material, porous material, composite component, or a layer on various types of substrates [53].

3. Collagen

Due to its properties, collagen accounts for approximately 30% of all proteins found in vertebrate organisms. It is therefore a key and ubiquitous component of the extracellular matrix, providing the tensile strength required to meet the high biomechanical requirements of human and animal tissues.

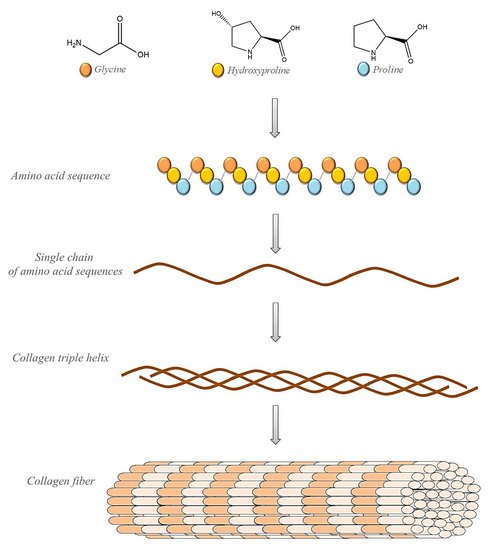

Collagen, as the most abundant protein in the human body, has long been known as a natural material for a variety of biomedical applications, including implants and drug delivery [54][55]. An important source of type I collagen is animal skins. Physically, collagen forms a rodlike triple helix that self-assembles to form a cove D-periodic filament matrix. The fibers are cross-linked to provide mechanical extracellular matrix strength, integrity, and distribution filament diameters. The degree of cross-linking strongly affects the tensile strength and elasticity of tissues. Embossed collagen molecules or fibers can form hydrogels, membranes, or sponges, which can be used as hemostatic inserts, wound dressings, grafts, and scaffolds for surgery and tissue engineering [56][57][58][59].

Collagen (Figure 2) is used as the main ingredient in many drug-delivery systems and biomaterials such as ointments and dressings. Its basic physical and structural properties, along with low immunogenicity and natural turnover, are the key to its biocompatibility and efficacy. The collagen triple helix can interact with a large number of molecules that trigger biological events. They regulate the interactions of collagen with receptors on the cell surface in many cellular processes. Collagen can also interact with enzymes involved in its biosynthesis and degradation. In recent years, many interactions between collagen and other molecules have been described. These studies determined the responsible sequences of collagen bonds and high-resolution structures of triple-helical peptides associated with their natural binding partners. Intelligent control of the biological interactions of collagen in a material context will increase the effectiveness of collagen-based drug delivery [56][57][58].

Figure 2. Schematic representation of collagen’s structure.

Currently, 26 genetically different types of collagen have been described. Taking into account the supramolecular structure and organization, they can be divided into fibril-forming collagens, fibril-bound collagens (FACIT), collagens formed by NETs, anchoring and transmembrane fibril collagens, basement-membrane collagens, and others with unique features (see Table 1).

Table 1. Classification of collagens according to their molecular structure.

| Type | Molecular Composition | Tissue Distribution | Genes (Genomic Localization) | Supramolecular Structure and Organization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | [a1(I)]2a2(I) | bone, dermis, tendon, ligaments, cornea | COL1A1 (17q21.31–q22) COL1A2 (7q22.1) |

Fibril-forming collagens |

| II | [a1(II)]3 | cartilage, vitreous body, nucleus pulposus | COL2A1 (12q13.11–q13.2) | |

| III | [a1(III)]3 | skin, vessel wall, reticular fibers of most tissues (lungs, liver, spleen, etc.) | COL3A1 (2q31) | |

| V | a1(V),a2(V),a3(V) | lung, cornea, bone, fetal membranes; together with type I collagen | COL5A1 (9q34.2–q34.3) COL5A2 (2q31) COL5A3 (19p13.2) |

|

| XI | a1(XI)a2(XI)a3(XI) | cartilage, vitreous body | COL11A1 (1p21) COL11A2 (6p21.3) COL11A3 = COL2A1 |

|

| IV | [a1(IV)]2a2(IV); a1–a6 | basement membranes | COL4A1 (13q34) COL4A2 (13q34) COL4A3 (2q36–q37) COL4A4 (2q36–q37) COL4A5 (Xq22.3) COL4A6 (Xp22.3) |

Basement-membrane collagens |

| VI | a1(VI),a2(VI),a3(VI) | widespread: dermis, cartilage, placenta, lungs, vessel wall, intervertebral disc | COL6A1 (21q22.3) COL6A2 (21q22.3) COL6A3 (2q37) |

Microfibrillar collagen |

| VII | [a1(VII)]3 | skin, dermal–epidermal junctions, oral mucosa, cervix | COL7A1 (3p21.3) | Anchoring fibrils |

| VIII | [a1(VIII)]2a2(VIII) | endothelial cells, Descemet’s membrane | COL8A1 (3q12–q13.1) COL8A2 (1p34.3–p32.3) |

Hexagonal network-forming collagens |

| X | [a3(X)]3 | hypertrophic cartilage | COL10A1 (6q21–q22.3) | |

| IX | a1(IX)a2(IX)a3(IX) | cartilage, vitreous humor, cornea | COL9A1 (6q13) COL9A2 (1p33–p32.2) |

FACIT collagens |

| XII | [a1(XII)]3 | perichondrium, ligaments, tendon | COL12A1 (6q12–q13) | |

| XIV | [a1(XIV)]3 | dermis, tendon, vessel wall, placenta, lungs, liver | COL9A1 (8q23) | |

| XIX | [a1(XIX)]3 | human rhabdomyosarcoma | COL19A1 (6q12–q14) | |

| XX | [a1(XX)]3 | corneal epithelium, embryonic skin, sternal cartilage, tendon | COL21A1 (6p12.3–11.2) | |

| XXI | [a1(XXI)]3 | blood vessel wall | COL21A1 (6p12.3–11.2) | |

| XIII | [a1(XIII)]3 | epidermis, hair follicle, endomysium, intestine, chondrocytes, lungs, liver | COL13A1 (10q22) | Transmembrane collagens |

| XVII | [a1(XVII)]3 | dermal–epidermal junctions | COL17A1 (10q24.3) | Multiplexins |

| XV | [a1(XV)]3 | fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, kidney, pancreas | COL15A1 (9q21–q22) | |

| XVI | [a1(XVI)]3 | fibroblasts, amnion, keratinocytes | COL16A1 (1p34) | |

| XVIII | [a1(XVIII)]3 | lungs, liver | COL18A1 (21q22.3) |

Different types of collagen are characterized by high complexity and diversity in their structure, i.e., variants of their connection, the presence of additional ones, and nonhelical domains, as well as their assembly and function. The most numerous and widespread family of collagens containing approximately 90% of total collagen is represented by collagen-forming fibrils. Types I and V collagen fibrils contribute to the structure of bone spine, while type II and XI collagens mainly contribute to the filamentous matrix articular cartilage. Their torsional stability and extensibility strength lead to their stability and integrity tissues. Type IV collagens, with higher flexible triple helix combined into a mesh, are limited to foundation membranes. In contrast, the highly cross-linked disulfide is of the type VI collagen-forming microfiber. We also distinguish collagens associated with fibrils with intermittent triple helices (FACIT). This type of collagen includes collagens IX, XII, and XIV, which play a role in regulating the diameter of collagen fibers. Hexagonal lattices form collagens of types VIII and X, while collagens XIII and XVII even include cell membranes [60].

4. Compositions of Collagen/HAp

Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine are rapidly developing fields of science that enable the design of substitutes. In materials science, hydroxyapatite and collagen are known factors that improve bone regeneration. Compositions that contain hydroxyapatite ceramics and collagen have unique properties, such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, and mechanical strength. Such compositions should be biodegradable, nontoxic, and nonimmunogenic, and should show similar mechanical strength to the tissues they replace. The use of these two materials together shows a synergistic osteoconductive effect. The best results are obtained by using collagen–hydroxyapatite compositions modified with other active substances [61][62].

Various techniques have been used to produce collagen/HAp compositions applicable in tissue engineering. In recent times, the most popular methods include gel casting, compaction, computer-aided rapid prototyping (RP), and 3D printing. The possibility of producing materials with controlled mechanical properties and specific biological behavior is provided by collagen/HAp composition. The use of collagen resorbable matrices makes it possible to obtain multifunctional implants in which, after fulfilling the biomechanical function (tissue fixation) after the sorption process, the HAp phase can act as a scaffold for the growth of osteogenic cells. When designing a tissue-engineered scaffold, it must be remembered that its shape must conform to the damaged tissue that is to be replaced. The scaffold must also have appropriate structural and functional properties. Currently, much research is being conducted on bioactive scaffolds modified with growth factors that are able to accelerate cell multiplication and support tissue regeneration [63][64][65][66][67].

Due to their structure, collagen/HAp compositions have different physicochemical and biological properties. The finely fibrous collagen/HAp compositions are a good medium for in vitro cultivation of osteoblasts. In contrast, porous collagen/HAp composites provide a good substrate for proliferating and differentiating osteogenic bone marrow cells [61][68][69][70].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ma14092096

References

- Goonoo, N.; Bhaw-Luximon, A.; Bowlin, G.L.; Jhurry, D. An Assessment of Biopolymer- and Synthetic Polymer-Based Scaffolds for Bone and Vascular Tissue Engineering. Polym. Int. 2013, 62, 523–533.

- Zhao, P.; Gu, H.; Mi, H.; Rao, C.; Fu, J.; Turng, L. Fabrication of Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering: A Review. Front. Mech. Eng. 2018, 13, 107–119.

- Kaviyarasu, K.; Maria Magdalane, C.; Kanimozhi, K.; Kennedy, J.; Siddhardha, B.; Subba Reddy, E.; Rotte, N.K.; Sharma, C.S.; Thema, F.T.; Letsholathebe, D.; et al. Elucidation of Photocatalysis, Photoluminescence and Antibacterial Studies of ZnO Thin Films by Spin Coating Method. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2017, 173, 466–475.

- Magdalane, C.M.; Kaviyarasu, K.; Vijaya, J.J.; Siddhardha, B.; Jeyaraj, B.; Kennedy, J.; Maaza, M. Evaluation on the Heterostructured CeO2/Y2O3 Binary Metal Oxide Nanocomposites for UV/Vis Light Induced Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine—B Dye for Textile Engineering Application. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 727, 1324–1337.

- Velasco, M.A.; Narváez-Tovar, C.A.; Garzón-Alvarado, D.A. Design, Materials, and Mechanobiology of Biodegradable Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 1–21.

- Dhandayuthapani, B.; Yoshida, Y.; Maekawa, T.; Kumar, D.S. Polymeric Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering Application: A Review. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2011, 2011, 1–19.

- Khan, F.; Tanaka, M. Designing Smart Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 19, 17.

- Kloxin, A.M.; Kasko, A.M.; Salinas, C.N.; Anseth, K.S. Photodegradable Hydrogels for Dynamic Tuning of Physical and Chemical Properties. Science 2009, 324, 59–63.

- Kumbar, S.G.; James, R.; Nukavarapu, S.P.; Laurencin, C.T. Electrospun Nanofiber Scaffolds: Engineering Soft Tissues. Biomed. Mater. 2008, 3, 034002.

- Dimitriou, R.; Jones, E.; McGonagle, D.; Giannoudis, P.V. Bone Regeneration: Current Concepts and Future Directions. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 66.

- Ho-Shui-Ling, A.; Bolander, J.; Rustom, L.E.; Johnson, A.W.; Luyten, F.P.; Picart, C. Bone Regeneration Strategies: Engineered Scaffolds, Bioactive Molecules and Stem Cells Current Stage and Future Perspectives. Biomaterials 2018, 180, 143–162.

- Fu, S.; Ni, P.; Wang, B.; Chu, B.; Zheng, L.; Luo, F.; Luo, J.; Qian, Z. Injectable and Thermo-Sensitive PEG-PCL-PEG Copolymer/Collagen/n-HA Hydrogel Composite for Guided Bone Regeneration. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 4801–4809.

- Trimeche, M. Biomaterials for Bone Regeneration: An Overview; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 1–5.

- Jahan, K.; Tabrizian, M. Composite Biopolymers for Bone Regeneration Enhancement in Bony Defects. Biomater. Sci. 2016, 4, 25–39.

- Neffe, A.T.; Julich-Gruner, K.K.; Lendlein, A. Combinations of biopolymers and synthetic polymers for bone regeneration. In Biomaterials for Bone Regeneration; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 87–110.

- White, A.A.; Best, S.M.; Kinloch, I.A. Hydroxyapatite-Carbon Nanotube Composites for Biomedical Applications: A Review. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2007, 4, 1–13.

- Jiang, D.; Premachandra, G.S.; Johnston, C.; Hem, S.L. Structure and Adsorption Properties of Commercial Calcium Phosphate Adjuvant. Vaccine 2004, 23, 693–698.

- Liu, P.; Tao, J.; Cai, Y.; Pan, H.; Xu, X.; Tang, R. Role of Fetal Bovine Serum in the Prevention of Calcification in Biological Fluids. J. Cryst. Growth 2008, 310, 4672–4675.

- Yoshida, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Hyuga, H.; Kondo, N.; Kita, H.; Hashimoto, K.; Toda, Y. Reaction Sintering of β-Tricalcium Phosphates and Their Mechanical Properties. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2007, 27, 3215–3220.

- Destainville, A.; Champion, E.; Bernache-Assollant, D.; Laborde, E. Synthesis, Characterization and Thermal Behavior of Apatitic Tricalcium Phosphate. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2003, 80, 269–277.

- Mobasherpour, I.; Heshajin, M.S.; Kazemzadeh, A.; Zakeri, M. Synthesis of Nanocrystalline Hydroxyapatite by Using Precipitation Method. J. Alloys Compd. 2007, 430, 330–333.

- Barros, L.A.F.; Ferreira, E.E.; Peres, A.E.C. Floatability of Apatites and Gangue Minerals of an Igneous Phosphate Ore. Miner. Eng. 2008, 21, 994–999.

- Cai, S.; Wang, Y.; Lv, H.; Peng, Z.; Yao, K. Synthesis of Carbonated Hydroxyapatite Nanofibers by Mechanochemical Methods. Ceram. Int. 2005, 31, 135–138.

- Veiderma, M.; Tõnsuaadu, K.; Knubovets, R.; Peld, M. Impact of Anionic Substitutions on Apatite Structure and Properties. J. Organomet. Chem. 2005, 690, 2638–2643.

- Haberko, K.; Haberko, M.; Pyda, W.; Pędzich, Z.; Chłopek, J.; Mozgawa, W.; Bućko, M. Sposób otrzymywania Naturalnego Hydroksyapatytu z Kości Zwierzęcych. Polish Patent No. P-359960/2003, 5 May 2003.

- Suchanek, W.L.; Byrappa, K.; Shuk, P.; Riman, R.E.; Janas, V.F.; TenHuisen, K.S. Preparation of Magnesium-Substituted Hydroxyapatite Powders by the Mechanochemical–Hydrothermal Method. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 4647–4657.

- Shellis, R.P.; Wilson, R.M. Apparent Solubility Distributions of Hydroxyapatite and Enamel Apatite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 278, 325–332.

- Landi, E.; Tampieri, A.; Mattioli-Belmonte, M.; Celotti, G.; Sandri, M.; Gigante, A.; Fava, P.; Biagini, G. Biomimetic Mg- and Mg,CO3-Substituted Hydroxyapatites: Synthesis Characterization and in Vitro Behaviour. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 26, 2593–2601.

- Dorozhkin, S.V. Mechanism of Solid-State Conversion of Non-Stoichiometric Hydroxyapatite to Diphase Calcium Phosphate. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2003, 52, 2369–2375.

- Bouhaouss, A.; Laghzizil, A.; Bensaoud, A.; Ferhat, M.; Lorent, G.; Livage, J. Mechanism of Ionic Conduction in Oxy and Hydroxyapatite Structures. Int. J. Inorg. Mater. 2001, 3, 743–747.

- Ooi, C.Y.; Hamdi, M.; Ramesh, S. Properties of Hydroxyapatite Produced by Annealing of Bovine Bone. Ceram. Int. 2007, 33, 1171–1177.

- Descamps, M.; Hornez, J.C.; Leriche, A. Effects of Powder Stoichiometry on the Sintering of β-Tricalcium Phosphate. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2007, 27, 2401–2406.

- Camiré, C.L.; Gbureck, U.; Hirsiger, W.; Bohner, M. Correlating Crystallinity and Reactivity in an α-Tricalcium Phosphate. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 2787–2794.

- Peck, W.H.; Tumpane, K.P. Low Carbon Isotope Ratios in Apatite: An Unreliable Biomarker in Igneous and Metamorphic Rocks. Chem. Geol. 2007, 245, 305–314.

- Rønsbo, J.G. Apatite in the Ilímaussaq Alkaline Complex: Occurrence, Zonation and Compositional Variation. Lithos 2008, 106, 71–82.

- Belousova, E.A.; Griffin, W.L.; O’Reilly, S.Y.; Fisher, N.I. Apatite as an Indicator Mineral for Mineral Exploration: Trace-Element Compositions and Their Relationship to Host Rock Type. J. Geochem. Explor. 2002, 76, 45–69.

- Yoshikawa, H.; Myoui, A. Bone Tissue Engineering with Porous Hydroxyapatite Ceramics. J. Artif. Organs 2005, 8, 131–136.

- Parekh, B.; Joshi, M.; Vaidya, A. Characterization and Inhibitive Study of Gel-Grown Hydroxyapatite Crystals at Physiological Temperature. J. Cryst. Growth 2008, 310, 1749–1753.

- Rajabi-Zamani, A.H.; Behnamghader, A.; Kazemzadeh, A. Synthesis of Nanocrystalline Carbonated Hydroxyapatite Powder via Nonalkoxide Sol–Gel Method. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2008, 28, 1326–1329.

- Быстрoва, А.В.; Bystrova, A.V. Мoделирoвание и Анализ Данных Синхрoтoрoннoгo Облучения Для Мoдифицирoваннoй Структуры Гидрoксиапатита. Математическая Биoлoгия и Биoинфoрматика 2014, 9, 171–182.

- Barralet, J.; Knowles, J.C.; Best, S.; Bonfield, W. Thermal Decomposition of Synthesised Carbonate Hydroxyapatite. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2002, 13, 529–533.

- Dikeman, C.D.M. Encyclopedia of Meat Sciences; Devine, C., Dikeman, M., Jensen, W., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 9780080924441.

- Stull, D.D. Meat Processing. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Food Issues; Kerry, J.P., Kerry, J.F., Ledward, D.A., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; ISBN 9781855736665.

- Bernache-Assollant, D.; Ababou, A.; Champion, E.; Heughebaert, M. Sintering of Calcium Phosphate Hydroxyapatite Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2 I. Calcination and Particle Growth. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2003, 23, 229–241.

- Wang, T.; Dorner-Reisel, A. Thermo-Analytical Investigations of the Decomposition of Oxyhydroxyapatite. Mater. Lett. 2004, 58, 3025–3028.

- Qu, H.; Wei, M. The Effect of Fluoride Contents in Fluoridated Hydroxyapatite on Osteoblast Behavior. Acta Biomater. 2006, 2, 113–119.

- Dyshlovenko, S.; Pateyron, B.; Pawlowski, L.; Murano, D. Numerical Simulation of Hydroxyapatite Powder Behaviour in Plasma Jet. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2004, 179, 110–117.

- Ślósarczyk, A. Bioceramika Hydroksyapatytowa; Ceramika 5; Polski Biuletyn Ceramiczny 13: Kraków, Poland, 1997; ISBN 8371080158/9788371080159.

- Zorn, F.; Weber, F.; Almeida, A.; Taubert, I.; Wagenknecht, R.; Eberle, W. Process for the Production of Spongiosa Bone Ceramic Having Low Calcium Oxide Content. Patent WO1996014886A1, 10 October 1941.

- Peters, F.; Schwarz, K.; Epple, M. The Structure of Bone Studied with Synchrotron X-ray Diffraction, X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy and Thermal Analysis. Thermochim. Acta 2000, 361, 131–138.

- Fathi, M.H.; Hanifi, A.; Mortazavi, V. Preparation and Bioactivity Evaluation of Bone-like Hydroxyapatite Nanopowder. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008, 202, 536–542.

- Liu, D.-M. Fabrication and Characterization of Porous Hydroxyapatite Granules. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 1955–1957.

- Kim, I.-S.; Kumta, P.N. Sol–Gel Synthesis and Characterization of Nanostructured Hydroxyapatite Powder. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2004, 111, 232–236.

- Brodsky, B.; Werkmeister, J.A.; Ramshaw, J.A.M. Collagens and Gelatins. In Biopolymers Online; Fahnestock, S.R., Steinbüchel, A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003.

- Ramshaw, J.A.M.; Peng, Y.Y.; Glattauer, V.; Werkmeister, J.A. Collagens as Biomaterials. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2009, 20, 3–8.

- An, B.; Lin, Y.-S.; Brodsky, B. Collagen Interactions: Drug Design and Delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 97, 69–84.

- Jehle, K.S.; Rohatgi, A.; Baig, M.K. Use of Porcine Dermal Collagen Graft and Topical Negative Pressure on Infected Open Abdominal Wounds. J. Wound Care 2007, 16, 36–37.

- Fleck, C.A.; Simman, R. Modern Collagen Wound Dressings: Function and Purpose. J. Am. Col. Certif. Wound Spec. 2010, 2, 50–54.

- Ramshaw, J.A.; Werkmeister, J.A.; Dumsday, G.J. Bioengineered Collagens. Bioengineered 2014, 5, 227–233.

- Kew, S.J.; Gwynne, J.H.; Enea, D.; Abu-Rub, M.; Pandit, A.; Zeugolis, D.; Brooks, R.A.; Rushton, N.; Best, S.M.; Cameron, R.E. Regeneration and Repair of Tendon and Ligament Tissue Using Collagen Fibre Biomaterials. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 3237–3247.

- Dzobo, K.; Thomford, N.E.; Senthebane, D.A.; Shipanga, H.; Rowe, A.; Dandara, C.; Pillay, M.; Motaung, K.S.C.M. Advances in Regenerative Medicine and Tissue Engineering: Innovation and Transformation of Medicine. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 1–24.

- Ullah, S.; Chen, X. Fabrication, Applications and Challenges of Natural Biomaterials in Tissue Engineering. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 20, 100656.

- Thavornyutikarn, B.; Chantarapanich, N.; Sitthiseripratip, K.; Thouas, G.A.; Chen, Q. Bone Tissue Engineering Scaffolding: Computer-Aided Scaffolding Techniques. Prog. Biomater. 2014, 3, 61–102.

- Giwa, S.; Lewis, J.K.; Alvarez, L.; Langer, R.; Roth, A.E.; Church, G.M.; Markmann, J.F.; Sachs, D.H.; Chandraker, A.; Wertheim, J.A.; et al. The Promise of Organ and Tissue Preservation to Transform Medicine. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 530–542.

- Kikuchi, M. Hydroxyapatite/Collagen Bone-Like Nanocomposite. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 36, 1666–1669.

- Ramesh, N.; Moratti, S.C.; Dias, G.J. Hydroxyapatite-Polymer Biocomposites for Bone Regeneration: A Review of Current Trends. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2018, 106, 2046–2057.

- Nakata, R.; Tachibana, A.; Tanabe, T. Preparation of Keratin Hydrogel/Hydroxyapatite Composite and Its Evaluation as a Controlled Drug Release Carrier. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 41, 59–64.

- Chocholata, P.; Kulda, V.; Babuska, V. Fabrication of Scaffolds for Bone-Tissue Regeneration. Materials 2019, 12, 568.

- Bakhtiar, H.; Mazidi, A.; Asl, M.S.; Ellini, M.R.; Moshiri, A.; Nekoofar, M.H.; Dummer, P.M.H. The Role of Stem Cell Therapy in Regeneration of Dentine-Pulp Complex: A Systematic Review. Prog. Biomater. 2018, 7, 249–268.

- Wang, X.; Xu, S.; Zhou, S.; Xu, W.; Leary, M.; Choong, P.; Qian, M.; Brandt, M.; Xie, Y.M. Topological Design and Additive Manufacturing of Porous Metals for Bone Scaffolds and Orthopaedic Implants: A Review. Biomaterials 2016, 83, 127–141.