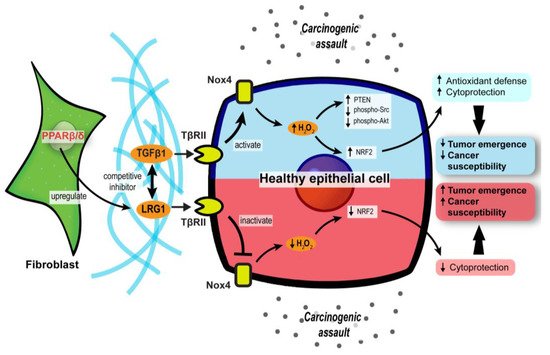

2. PPARβ/δ in CAFs Governs Redox Homeostasis and Affects Tumor Initiation

The differentiation of normal fibroblasts into CAFs is one of the cornerstones of early tumor initiation in many cancer types [

83,

84]. CAFs can disrupt the local ECM and deliver proliferative paracrine signals to support tumorigenic events. Interestingly, mice with fibroblast-selective

PPARβ/δ deletion developed fewer and smaller skin tumors than wild-type mice exposed to topical carcinogens [

85]. Similar results were recapitulated using chemically and genetically induced intestinal carcinogenesis in these mutant mice [

86], indicating that PPARβ/δ activity in stromal fibroblasts promotes tumor initiation. The delayed tumor emergence in the mutant mice was due to an enhanced antioxidant response in the epithelium. Mechanistically, PPARβ/δ-knockout fibroblasts markedly increase the Nox4-derived H

2O

2 production in the adjacent epidermis, subsequently triggering an RAF/MEK-mediated NRF2 activation that elicits a strong antioxidant and cytoprotective response [

85]. By reducing the phosphorylation of many tumor suppressors and oncogenes, NRF2 also increases the tumor suppressor activity of PTEN and reduces the oncogenic activity of Src and Akt, leading to delayed tumor growth [

85]. Hence, reducing the expression and activity of

PPARβ/δ in CAFs may provide a new therapeutic option to disrupt cancer susceptibility in the neighboring tumor epidermis.

Leucine-rich-alpha-2-glycoprotein 1 (LRG1) and TGFβ1 underpin a crucial process in the PPARβ/δ-mediated stromal–epithelial crosstalk. PPARβ/δ in fibroblasts upregulates the expression of LRG1, which blunts the epidermal response to TGFβ1 [

87]. Furthermore, exogenous LRG1 can also ablate the influence of TGFβ1 on ROS generation and NRF2 activity [

85]. In colorectal carcinoma and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients, the level of LRG1 in the TME and bloodstream is significantly higher than in healthy individuals and correlates positively with a more advanced cancer stage and poorer prognosis [

88,

89,

90]. This observation suggests a pro-tumorigenic role of LRG1. Surprisingly, the

LRG1 promoter has two putative PPAR response elements [

91]. The expression of

LRG1 is increased by a PPARβ/δ agonist, GW501516, which strongly suggests that LRG1 is a direct target of PPARβ/δ [

91]. Therefore, during the early stage of tumorigenesis, CAF PPARβ/δ may stimulate LRG1 expression, which interferes with TGFβ1-dependent redox homeostasis, to support a sustained oncogenic transformation in the surrounding tumor epithelium.

Collectively, these findings uncover a major role for stromal PPARβ/δ in the epithelial–mesenchymal communication and cellular oxidative response in tumor development (). Notably, this novel role of PPARβ/δ was primarily documented, so far, in nonmelanoma skin carcinoma and colorectal cancer models. Thus, further validation in other cancer models is necessary.

Figure 3. Stromal PPARβ/δ regulates epithelial redox homeostasis and oncogenesis. In carcinogenic assaults, TGFβ signaling in epithelial cells is activated to promote H2O2 synthesis, which subsequently activates NRF2 and reinforces the cytoprotection against carcinogens (blue upper compartment of the epithelial cell). However, fibroblast PPARβ/δ disrupts the protective mechanism by upregulating LRG1, which acts as a competitive inhibitor of TGFβ1 and dampens TGFβ signaling, resulting in increased cancer susceptibility and oncogenesis (red lower compartment of the epithelial cell).

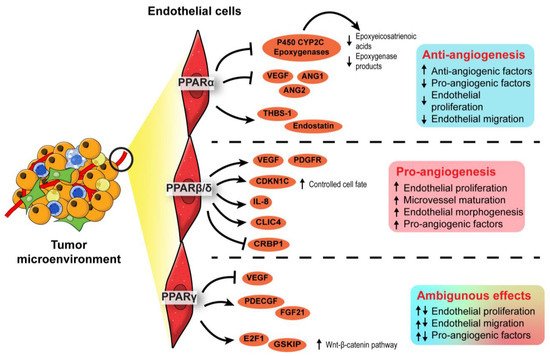

3. Endothelial PPARs Affect Angiogenesis in the Tumor Microenvironment

Hypoxic regions often arise because of rapid tumor growth, which outgrows the oxygen perfusion and nutrient supply from existing vasculature [

92]. Cancer cells mitigate the predicament by releasing pro-angiogenic factors that stimulate angiogenesis, which is affected by all three PPAR isotypes.

In terms of PPARα, synthetic PPARα agonists such as fenofibrate and Wy-14643 have demonstrated suppressive effects on endothelial cell proliferation, neovascularization, and tumor xenograft growth [

93,

94]. Such anti-angiogenic effects of PPARα agonists were lost in PPARα-deficient mice transplanted with PPARα-intact tumor cells, implying that PPARα activation in surrounding stromal cells, but not the tumor cells, attenuated tumor angiogenesis [

93,

94]. The underlying mechanism is associated with increased anti-angiogenic factors (i.e., thrombospondin-1 and endostatin) and the interference of pro-angiogenic factor biosynthesis (i.e., VEGF-A, angiopoietin-1, and angiopoietin-2), affecting VEGF- and FGF2-mediated endothelial proliferation and migration [

93,

95]. Furthermore, by transcriptionally suppressing the expression of endothelial P450 CYP2C epoxygenase, whose function is to catalyze arachidonic acid epoxidation, PPARα also diminishes the epoxygenase products, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, which are pro-angiogenic [

96]. Thus, PPARα activation in stromal endothelial cells inhibited the biosynthesis of pro-angiogenic factors while promoting the secretion of anti-angiogenic factors, thereby abrogating angiogenesis and limiting nutrient supply to attenuate tumor progression.

In contrast to PPARα, PPARβ/δ is a pro-angiogenic nuclear receptor in line with its wound healing properties [

97,

98,

99]. The activation of PPARβ/δ in endothelial cells by synthetic ligands or genetic manipulation consistently results in aberrant biosynthesis of VEGF, PDGFR, and c-KI, as well as accelerated endothelial cell proliferation and vascular formation [

100,

101]. In the TME, these pro-angiogenic changes stimulate the formation of a tumor with a higher vessel density, enhancing tumor feeding, oxygen provision, and metastasis capacity of the cancer cells [

101]. Interestingly, in PPARβ/δ knockout mice harboring experimental wild-type tumors, the endothelial cells forming the microvessels in the tumors appear immature, hyperplastic, and less well-organized, leading to abnormal microvasculature and restricted blood flow into the tumors [

102,

103]. Apart from conventional growth factors, other potential PPARβ/δ-dependent angiogenic mediators include CDKN1C [

102], IL-8 [

104], CLIC4, and CRBP1 [

105]. Considering its regulatory effects on many angiogenic genes and the strong linkages with advanced cancer stages, tumor recurrence, and distant metastasis, PPARβ/δ is identified as one of the pro-angiogenic signaling hubs in cancers [

103]. Thus, the pro-tumorigenic and pro-angiogenic activities of PPARβ/δ warrant the development of efficacious PPARβ/δ antagonists to be tested in cancer models.

Existing evidence on the role of PPARγ in angiogenesis remains ambiguous. Like PPARα, PPARγ activities in the TME are associated with the dysregulated production of angiogenic factors, especially platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor (PD-ECGF) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) [

106,

107]. Early studies generally concluded on an inhibitory effect of PPARγ ligands on endothelial cell proliferation in response to pro-angiogenic factors and endothelial tube formation [

108,

109], whereas subsequent investigations suggested otherwise [

110,

111]. Such conflicting findings may be attributable to the dosages of PPARγ ligands and endothelial cell types [

112]. Regardless of the pro- or anti-angiogenic properties, VEGF/VEGFR signaling is coherently implicated in the PPARγ-mediated effect [

108,

109,

110]. A recent study using endothelial-specific PPARγ knockout models shed new light on the role of this nuclear receptor in angiogenesis. In mature endothelial cells, PPARγ knockdown impaired proliferation, migratory properties, and tubule formation capacity [

111]. These impairments translated into the loss of circulating endothelial progenitor cells and angiogenic capacity in endothelial-specific PPARγ-deficient mice, which was reversed by the transplantation of wild-type bone marrow [

111]. Mechanistically, abolishing PPARγ in the endothelial cells disrupts E2F1-mediated Wnt signaling and GSK3B interacting protein activity, resulting in suppressed endothelial proliferation [

111]. Conceivably, the genetic models reinforce the pro-angiogenic activity of PPARγ in endothelial cells.

In short, PPARα and PPARβ/δ exert anti- and pro-angiogenic activities in the endothelial cells of TME, respectively. On the other hand, opposing roles have been reported for PPARγ in angiogenesis. The roles of each PPAR isotype in angiogenesis are summarized in . Notably, most findings on PPARγ are not established using oncogenic models. As the physiological cues in a TME are different from a normal condition, the true nature of PPARγ in cancer angiogenesis and tumor epithelium-endothelium crosstalk requires further investigation.

Figure 4. Angiogenic role of PPARs in endothelial cells. In the endothelial cells, PPARα exhibits an anti-angiogenic effect by inhibiting endothelial proliferation, whereas PPARβ/δ appears pro-angiogenic by ensuring proper endothelial morphogenesis and vascular maturation. The role of PPARγ in angiogenesis is conflicting and warrants further investigation.

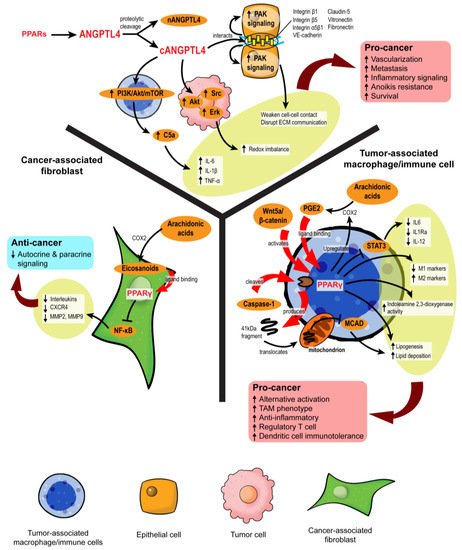

4. PPAR-Dependent Autocrine and Paracrine Signaling

Autocrine signaling facilities self-stimulation, while paracrine signaling allows local cell–cell communication. In the TME, both forms of cell signaling are imperative to coordinate every stage of oncogenesis, alerting the tumor cells how and when to proliferate, evade immune surveillance, escape from the existing microenvironment, and settle at a distal site. The transmission of complex messages in response to cellular stimuli is made possible by a plethora of secretory mediators, including cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, catalytic proteins, miRNAs, extracellular vesicles, and lipid compounds [

113]. Many of these messengers are directly or indirectly regulated by PPARs (). For instance, a new PPARγ agonist, CB13, remodels the exosomal contents from radio-resistant non-small cell lung cancer to promote endoplasmic reticulum stress and cell death via a PERK-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP axis [

114].

Figure 5. PPARs modulate stromal–epithelial crosstalk in the tumor microenvironment. PPARs affect autocrine and paracrine signaling in different stromal cells. In cancer-associated fibroblasts, PPARγ activation upon ligand binding represses NF-κB, alleviating the secretion of many autocrine and paracrine signals. However, in macrophages and immune cells, PPARγ activation is primarily linked to pro-cancer activities, such as the formation of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), increased regulatory T cells, and immunotolerance. ANGPTL4 is a target gene product of PPARs. Proteolytic cleavage of full-length ANGPTL4 yields nANGPTL4 and cANGPTL4 domains, of which the latter is a potent paracrine signal and key mediator of inflammatory signals, anoikis resistance, and metastasis.

4.1. Disruption of Pro-Tumor Signaling by PPARγ in CAFs

Eicosanoids, which are lipid signaling molecules and cognate ligands of PPARs, are the main drivers of PPAR activation in the TME. Major eicosanoid subfamilies include prostaglandins, thromboxanes, leukotrienes, and epoxygenated fatty acids, among which the prostaglandins are the most well-investigated. In colon cancers, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandin H2 (PGH2), is overexpressed in CAFs surrounding colon adenocarcinomas, leading to a buildup of intratumoral PGE2 [

61,

115]. However, the resultant activity of PPARs varies across different stromal cells. For instance, 15d-PGJ2 activates PPARγ and suppresses the proliferation of CAFs and expression of the ECM remodeling enzyme, MMP2 [

116]. By inhibiting NF-κB, TZD-activated PPARγ substantially lowers the expression of pro-inflammatory, pro-angiogenic, and pro-metastatic signaling molecules in CAFs, including IL-6, IL-8, CXCR4, MMP2, and MMP9, which further dampens pro-tumor crosstalk in the TME [

117,

118]. The repression of PPARγ activity also disturbs the quiescent state of hepatic and pancreatic stellate cells, compelling their differentiation into CAFs with highly aggressive phenotypes and inducing desmoplasia in the TME [

119,

120,

121,

122]. Despite some conflicting results [

123], PPARγ in CAFs can disrupt pro-tumorigenic paracrine signaling by suppressing the liberation of cytokines and chemokines.

4.2. PPARγ Propels the Formation of Tumor-Associated Macrophages

The role of PPARs in innate and adaptive immune cells has been extensively studied. Unlike CAFs, the activation of PPARα and PPARγ in macrophages favors an anti-inflammatory tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) phenotype [

124,

125]. Classical PPARγ ligands, namely rosiglitazone,

N-docosahexaenoyl ethanolamide, and

N-docosahexaenoyl serotonin, effectively block paracrine signals from cancer cells to sway the fate of macrophages to adopt alternative activation and reduce their STAT3-mediated pro-inflammatory response [

125]. In macrophages challenged with pathogens, WY14643 (PPARα agonist) and 15d-PGJ2 (PPARγ agonist) tip the balance towards the M2 phenotype by enhancing the expression of arginase I, Ym1 (chitinase 3-like 3), mannose receptor, TGF-β and increasing phagocytic capacity while diminishing M1 macrophage biomarkers [

126]. PPARγ antagonists and macrophage-specific PPARγ ablation attenuate these effects, clearly outlining the dependency of TAM differentiation on PPARγ [

127,

128].

Mechanistically, PPARγ agonism promotes lipid retention, lipogenesis, and PGE2 secretion in macrophages. The lipid metabolic changes are partly mediated by the Akt/mTOR pathway [

129]. On top of its role as a nuclear receptor and transcription factor, PPARγ is subject to cleavage by caspase-1 to yield a 41 kDa fragment that translocates to mitochondria and inhibits medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD). Such a non-canonical peptide–protein interaction can inhibit fatty acid oxidation, further aggravating lipid droplet accumulation and TAM formation [

130]. Likewise, in dendritic cells residing in the TME, PPARγ activation directed by Wnt5a/β-catenin paracrine signaling disrupts fatty acid oxidation and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-1 activity, subsequently leading to the generation of regulatory T cells, immunotolerance, and weakened immunotherapy response [

131]. These PPARγ activities create a “friendly” TME for cancer survival, which also coincides with the functional trajectory of macrophage PPARβ/δ [

132,

133].

Nonetheless, some findings support counterarguments. For example, Cheng et al. (2016) [

134] identified macrophage PPARγ as a key tumor suppressor and TAM modulator by abolishing Gpr132 expression. Van Ginderachter et al. (2006) [

135] agreed that PPARγ was highly expressed in TAMs, but further stimulation with synthetic and natural ligands could sabotage TAM-induced cytotoxic T lymphocyte suppression to confer an anti-tumor effect. The overexpression of PPARγ in macrophages promotes the upregulation of

PTEN, which is encapsulated in exosomes. The uptake of these macrophage-derived exosomes by adjacent cancer cells inhibits Akt, p38 MAPK, and migratory properties [

136]. Many eicosanoids are also packaged in these exosomes to achieve paracrine stimulation of PPARγ and augment the inhibitory effect on tumor EMT [

136].

Taken together, PPARγ acts as a master immuno-metabolic switch in immune cells that govern their fate and tumor-supporting role. Current consensus depicts that PPARγ exhibits a pro-tumorigenic effect in immune cells by promoting alternative activation, which contradicts its anticancer properties in tumor epithelium and CAFs. On the other hand, the related information on other PPAR isotypes in this aspect is somewhat limited. Interestingly, a recent study unveiled that fatty acid-enriched cancer exosomes markedly activate PPARα in tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells, resulting in mitochondrial overdrive and impaired dendritic cell-mediated CD8

+ cytotoxic T-cell priming [

137]. These exciting findings strongly suggest an immuno-metabolic regulatory role of PPARα in the TME similar to PPARγ. Such a novel activity of PPARα warrants further investigation.

4.3. Role of ANGPTL4 in Stromal–Epithelial Crosstalk

Growing evidence suggests a role of angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4) in cancer and stromal-epithelial communication. ANGPTL4 is a secretory protein that belongs to a family of ANGPTL proteins that share high amino acid sequence similarity with the angiopoietin (ANG) family [

138,

139]. Its expression is regulated by all three PPAR isotypes and PGE2, especially during major metabolic challenges such as starvation and hypoxia [

139,

140,

141]. The native full-length ANGPTL4 can undergo proteolytic cleavage to yield C-terminal (cANGPTL4) and N-terminal (nANGPTL4) chains, each with distinct biological activities [

142]. The nANGPTL4 domain is primarily responsible for lipid and glucose metabolism, while the cANGPTL4 domain is closely linked to tumorigenic activities, notably angiogenesis, anoikis resistance, and metastasis [

143]. Thus, we will be focusing more on the cANGPTL4 fragment.

High expression of ANGPTL4 has been reported in ovarian, urothelial, and breast tumor biopsies, particularly in the CAAs [

144,

145,

146]. The ANGPTL4 overexpression in CAAs is directed by IL-1β from neighboring TAMs with activated NLRC4 inflammasome and can be exacerbated by tumor hypoxia [

147], resulting in cANGPTL4 aggregation in the TME. The cANGPTL4 interacts with integrins β1, β5, α5β1, VE-cadherin, and claudin-5 to induce PAK signaling and weaken cell–cell contacts [

148,

149]. Moreover, it also disrupts cell–ECM communication through its interaction with vitronectin and fibronectin [

150]. The destabilization of cell junctions is then translated to greater intratumoral vascularization and migratory capacity of the malignant cells [

151,

152,

153].

By manipulating redox homeostasis and activating several pro-survival mechanisms such as FAK/Src, PI3K/Akt, Erk signaling, ANGPTL4 markedly sharpens the resilience of tumor cells and confers anoikis resistance [

154,

155,

156]. Our latest report showed that exogenous ANGPTL4 activates macrophages and induces hypercytokinemia via PI3K/Akt-mediated complement component 5a (C5a) activation [

157]. This finding indicates a modifying role of ANGPTL4 in TAM functionality and paracrine signaling in the TME. Thus, ANGPTL4 may act as a powerful autocrine and paracrine signaling effector of PPARs that can shape a supportive environment for cancer progression. Further investigations on the therapeutic feasibility of targeting ANGPTL4 are warranted.

5. Stromal PPARγ Modulates Tumor Metastasis

Only a handful of studies have investigated stromal PPAR activities on metastasis, and the results are conflicting. In myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), deficiency of lysosomal acid lipase (

lal−/−) impaired the production of PPARγ ligands, which led to reduced PPARγ activity, ROS accumulation, and mTOR-mediated tumor metastasis [

158]. Following intravenous injection of B16 melanoma cells, increased lung metastases were observed in mice with myeloid-specific PPARγ knockout, further reinforcing the role of MDSCs’ PPARγ in metastasis. Contradictorily, a PPARγ agonist, pioglitazone, has been shown to promote alternative activation of macrophages in the TME [

159]. These pro-tumorigenic myeloid cells can synthesize TGFβ1 to promote EMT of surrounding tumor cells [

160]. Although the true role of stromal PPARγ in metastasis remains debatable, a recent study showed that astrocytes liberate polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are PPARγ agonists, to promote the extravasation of circulating cancer cells into the brain while PPARγ antagonists can reduce brain metastatic burden in vivo [

161]. Astrocyte–cancer cell communication is also mediated by TGF-β2 and ANGPTL4, the latter of which is an effector of PPARs [

162]. Hence, PPARγ may serve as a nutritional cue to provoke the invasion of metastatic cells into a nutrient-rich environment. The results also argue for the potential use of PPARγ blockade to treat brain metastasis.