Biofortification is widely regarded as a very valuable technique that increases the availability of micronutrients (vitamin A, selenium, zinc, iron and other micronutrients) absorbed by plants and transferred from them to consumers.

- biofortification

- marketing

- economic approaches

- health

- innovation

- nutrition

1. Introduction

The main objective of agricultural innovations, whether technological, agronomic or genetic, has been to increase the final yields. Until the 1990s, limited attention was given to improving nutritional qualities. In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to “hidden hunger,” two research terms used to indicate people around the world who suffer from vitamin and micronutrient deficiencies. Unfortunately, malnutrition is still a global health problem with many related diseases [1]. This phenomenon has a significant socio-economic impact and has contributed, together with difficult social and environmental conditions to the current situation in low- and middle-income countries [2,3]. In 2015, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [4] aimed to eradicate health and poverty problems, world hunger, reduce child and maternal mortality, and overcome malnutrition resulting from a scarcity of food resources [5]. Biofortification can be useful in combating malnutrition, which is a major challenge, particularly in developing countries [6,7].

In this context, plant biotechnology applied to biofortification of staple crops has offered a powerful tool to counteract these deficiencies by providing nutritionally enhanced crops. The availability of foods enriched with beneficial substances such as antioxidants, vegetable fibers, vitamins, and minerals has increased, as consumers [8] are attracted to labels such as “low fat,” “low sugar,” “no hydrogenated fats,” “low sodium,” in parallel with the promotion of a healthy lifestyle. All these different products have in common the fact that they provide health benefits and as such have been classified as functional food [9,10]. In recent years, the subject has become highly topical, in accordance with the new requirements expressed by an increasingly globalized market. Although there has been increasing discussion of biofortified products for some years now, there is some confusion, especially regarding the definition, which generates a lot of uncertainty for consumers and operators in the sector [11,12]. The lack of an unambiguous interpretation of the term often leads to confusion between the concept of biofortified products and other products, such as GMOs (genetically modified organisms), which they are increasingly referred to. Over the years, the various strands of research have addressed this issue, each with their own expertise, highlighting the specificities and peculiarities of these products, paving the way for further developments [13,14].

2. The Complexity of Dimensions of the Biofortified Products

2.1. Biofortification, Human Health and Reducing Hunger

Biofortification is considered a new method to support public health to combat major nutritional deficiencies (vitamin A, iron, zinc), especially in developing countries. Food crops such as rice, wheat, maize, and potatoes are enriched with micronutrients through cultivation techniques [24,25,26]. A distinction is then made between poor and rich countries. This is because the huge majority of the world′s population consumes foods composed of cereals (rice, corn, wheat, soya, cassava), the so-called “staple crops.” These crops basically meet the caloric requirements, but have a low bioavailability of essential trace elements. In underdeveloped countries, this limitation is particularly widespread, as a varied and balanced diet, with a daily intake of fruit, vegetables, meat and fish, sufficient to provide the necessary doses of vitamins and minerals, is not always possible [5,27,28]. In industrialized countries, the situation is different, as inadequate nutrition is not linked to a lack of food, but rather to its misuse. In addition to vitamins and minerals, which are necessary for good health, there are compounds such as “phytonutrients,” which help our bodies to increase cell metabolism [29,30]. The carotenoids and polyphenols are often linked together in an antioxidant diet [31,32].

2.2. Biofortification and Technical-Normative Definition

The techniques for obtaining biofortified products, such as enriched products, inevitably lead to several elements of contact with functional food [33]. On the basis of this consideration, it is necessary to attribute the possible classifications of functional products, which can take the form of fortified food (foods obtained through a technological process of fortification that makes them more nutritious), enriched food (in which the percentage of one or more nutrients already present in nature is increased), supplementary food (subcategory of fortified foods) [9,10].

The definition of functional foods, produced at institutional level (e.g., ILSI Europe in the context of the European Concerted Action on Functional Food Science—Concert Action “FUFOSE”) is not, as is well-known, unambiguous, to the point that it has led to the inclusion in the sector of products that are not (e.g., pharmaceutical and herbal products with common beneficial/curative properties) and that cannot boast these characteristics [34,35]. Today functional foods are considered as such if they represent “a normal daily food” (they are not food supplements or a medicine, nutraceuticals or herbal products in tablet form); if they are presented to the consumer in a manner consistent with the content of EU Regulation 1924/2006 on nutrition and health claims made on foods; if they contain claims relating to the improvement of a biological function or claims relating to the reduction of the risk of disease occurrence [36,37].

2.3. Biofortification, Economy, and Market

Given the nutritional benefits of biofortification, most consumers want all foods in their diet to be biofortified [52,53]. A consumer choice tool may be the label. Food labels are, as are well-known, the means by which the producer communicates useful information about the food to the consumer. The label, is identified as a guarantee of quality and a certain, beneficial effect [54,55,56,57,58]. Therefore, the terms “biofortification” and “biofortified food” on the product label are important elements of consumer assessment [59].

2.4. Biofortification, Cultivation, Factors Influencing Agronomic Technical Choices

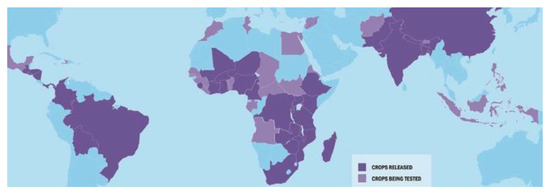

The international scientific community has intensified its efforts to promote development and dissemination of biofortified crops. According to an estimate conducted by HarvestPlus in 2017 (see Figure 2), there are currently more than 150 biofortified varieties, bundled in 12 crops, that have been authorized in 30 countries [70,71,72,73].

Figure 2. In purple, crops currently released commercially. In lilac, crops being tested [70].

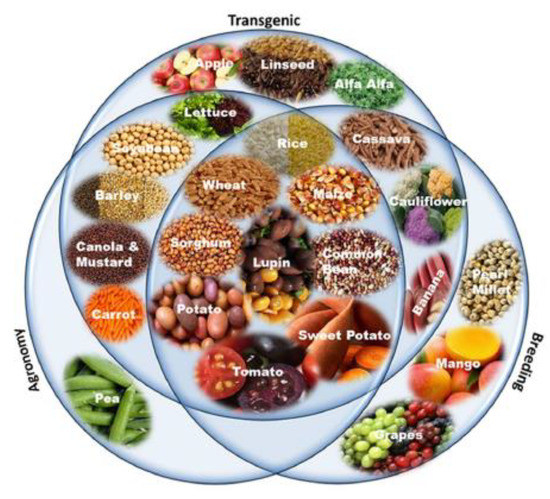

Biofortification of staple crops can be achieved through three different approaches, transgenic, conventional, and agronomic, based on biotechnology, breeding, and the use of mineral fertilizers, respectively [2,74]. Regardless of the method used, only with a multidisciplinary approach is it possible to “measure the nutritional value of biofortified products such as bio-accessibility and bio-availability [75,76].

In Figure 3, as highlighted by Garg, M.; it can be seen that several biofortified crops, including wheat, rice, maize, potato, and tomato were obtained through the application of all three strategies listed above [2,77].

Figure 3. Biofortified crops harvested through the three different approaches: agronomic; traditional breeding; transgenic [2].

The current results in genomic biofortification are certainly useful for the development of biofortified products as a sustainable solution to the problem of “hidden hunger,” to solve the lack of micronutrients, thus serving for human health and as an economic saver [77,78,79,80,81,82].

In this context, the new perspective of biofortification is that of “tailor-made plant nutrition” to obtain products for specific population groups, so-called “tailored foods.” In order to achieve this objective, the most suitable cultivation systems seem to be those without soil, because they allow a more appropriate management of plant nutrition, regulating the presence of the main nutrients in the plants by regulating the presence of the main mineral elements (calcium, iodine, zinc, selenium, silicon, iron, silicon, iron, etc.,) which are beneficial to human health or which may sometimes be harmful to consumers with specific metabolic alterations [75,84,85,86].

3. Future Research

tThe interest in biofortified products and their effects on consumers in emerging countries is gradually growing [89,90]. In fact, in several developing countries, biofortification is considered a valuable tool to counteract food insecurity issues, although in these countries biofortification requires increasing public investment in agricultural research and infrastructure to be successful [11,12,91].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/asi4020030