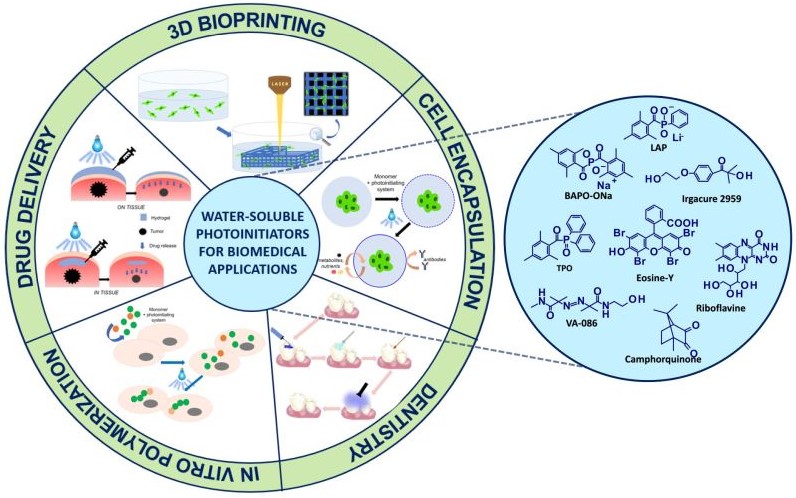

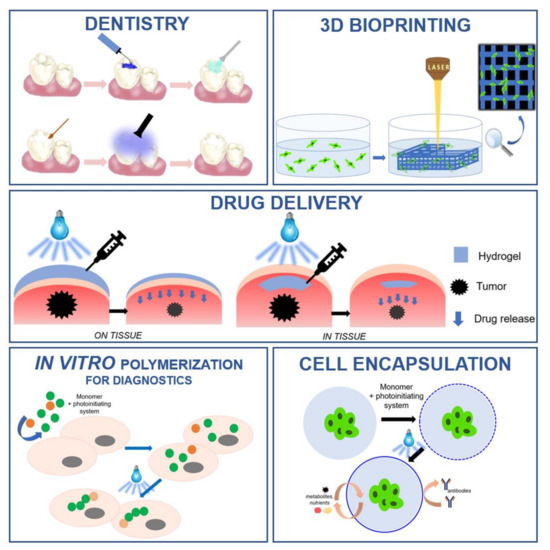

Light-initiated polymerization processes are currently an important tool in various industrial fields. The advancement of technology has resulted in the use of photopolymerization in various biomedical applications, such as the production of 3D hydrogel structures, the encapsulation of cells, and in drug delivery systems. The use of photopolymerization processes requires an appropriate initiating system which, in biomedical applications, must meet additional criteria: high water solubility, non-toxicity to cells, and compatibility with visible low-power light sources. This article is a literature review on those compounds that act as photoinitiators of photopolymerization processes in biomedical applications. The division of initiators according to the method of photoinitiation was described and the related mechanisms were discussed. Examples from each group of photoinitiators are presented, and their benefits, limitations and applications are outlined.

- water-soluble photoinitiators

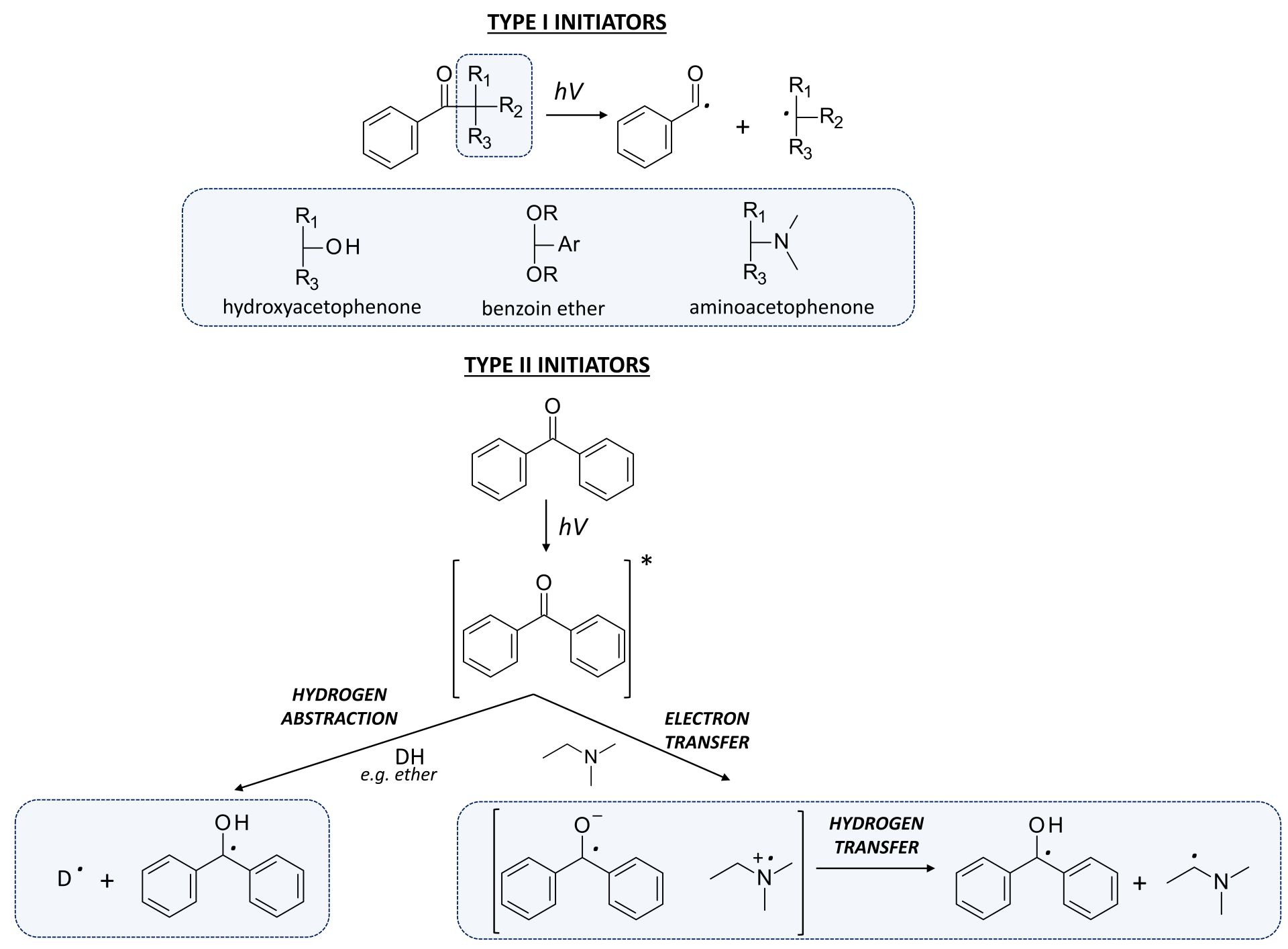

- type I photoinitiators

- type II photoinitiators

- two-photon initiators (2PP), photopolymerization

- biomedical applications

- free-radical photopolymerization

- cationic photopolymerization

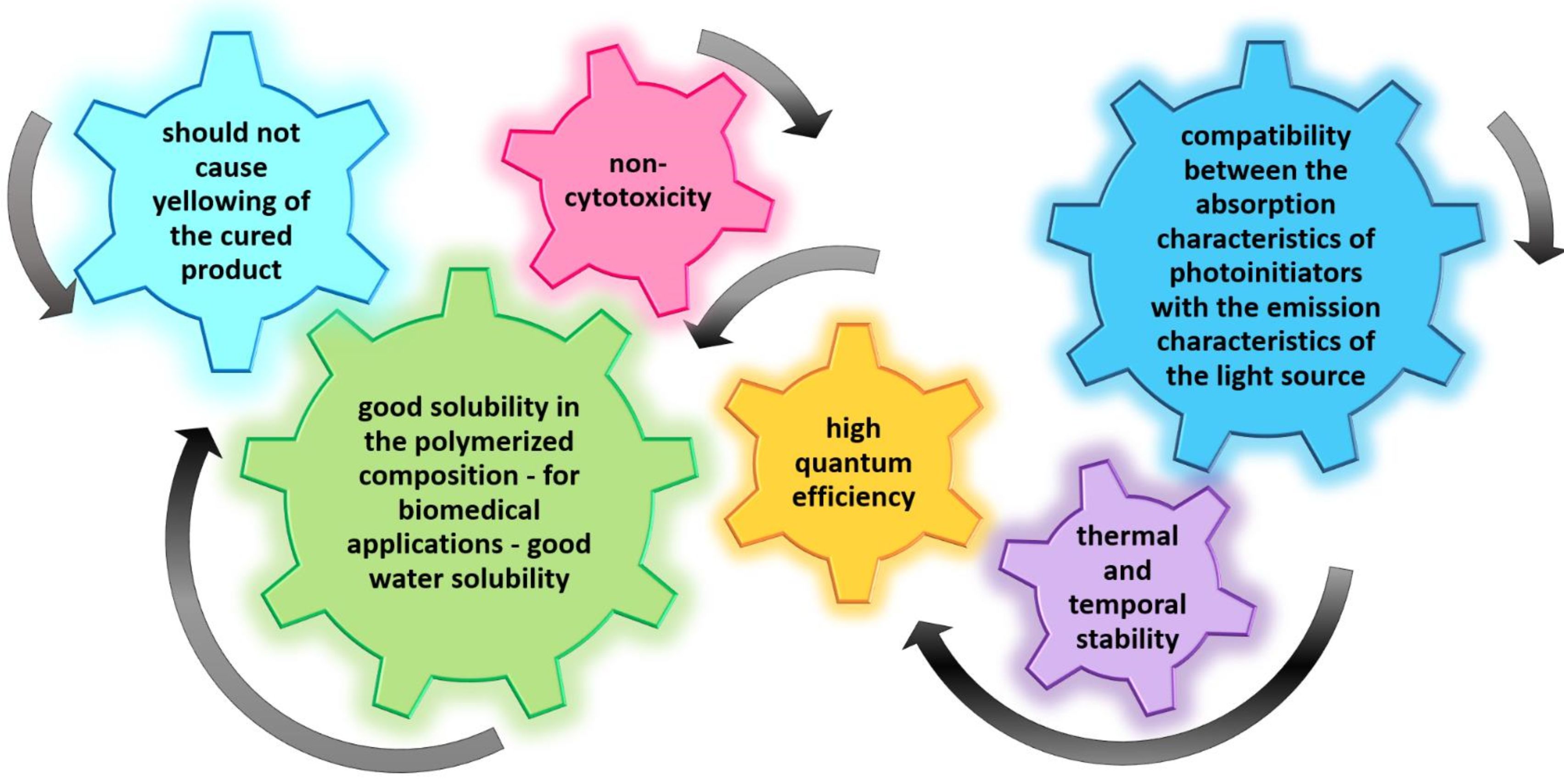

- compatibility between the absorption characteristics of photoinitiators and the emission characteristics of the light source

- high quantum efficiency

- good solubility in the polymerized composition – for biomedical applications – good water solubility

- non-cytotoxicity

- should not cause yellowing of the cured product

- thermal and temporal stability

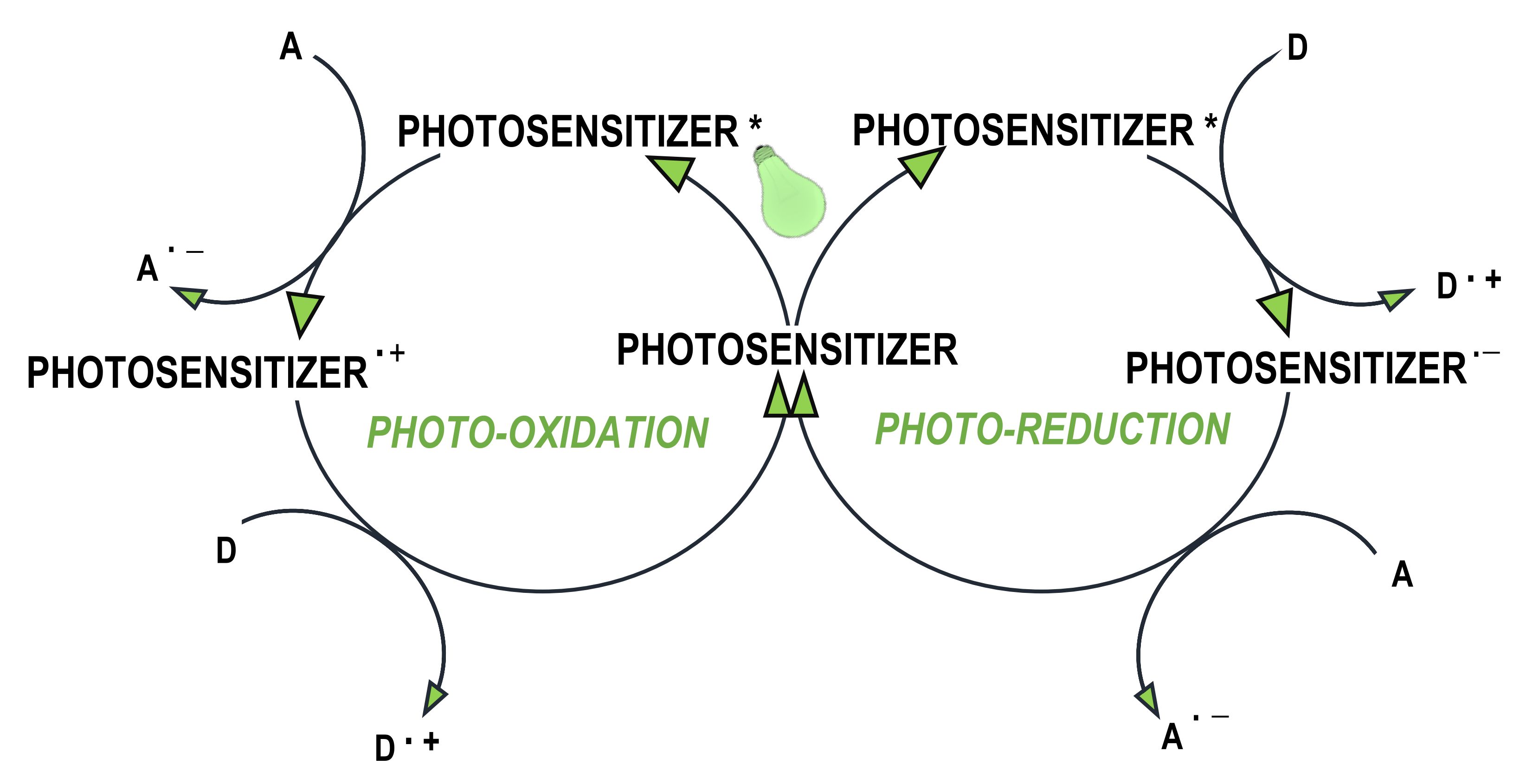

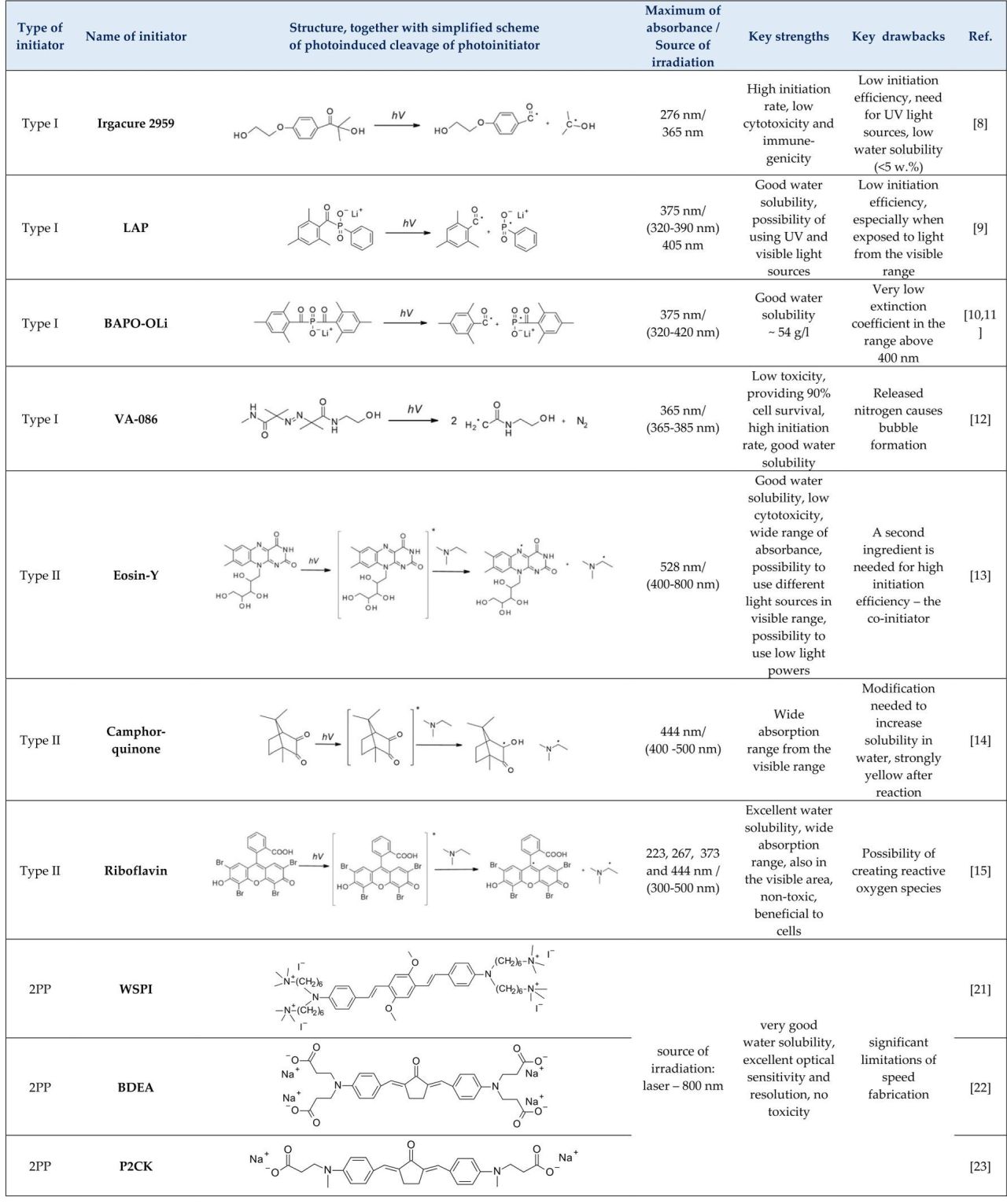

Figure 4. The photoinitiation process using: A. type I initiator; B. type II initiator.

- where the photosensitiser acts as an electron donor, the transfer of the electron to the co-initiator creates a cationic radical of the sensitiser particle and an anionic radical of the co-initiator;

- where the photosensitiser is an electron acceptor, it undergoes photoreduction, and the electron transfer products are the anionic radical formed on the sensitiser molecule and the cationic radical formed on the co-initiator

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/polym12051073

References

- Frederic Dumur; Recent advances on carbazole-based photoinitiators of polymerization. European Polymer Journal 2020, 125, 109503, 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2020.109503.

- Junyi Zhou; Xavier Allonas; Ahmad Ibrahim; Xiaoxuan Liu; Progress in the development of polymeric and multifunctional photoinitiators. Progress in Polymer Science 2019, 99, 101165, 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2019.101165.

- D. J. Lougnot; C. Turck; J. P. Fouassier; Water-soluble polymerization initiators based on the thioxanthone structure: a spectroscopic and laser photolysis study. Macromolecules 1989, 22, 108-116, 10.1021/ma00191a022.

- Anna Eibel; David E. Fast; Georg Gescheidt; Choosing the ideal photoinitiator for free radical photopolymerizations: predictions based on simulations using established data. Polymer Chemistry 2018, 9, 5107-5115, 10.1039/c8py01195h.

- Adina I. Ciuciu; Piotr J. Cywiński; Two-photon polymerization of hydrogels – versatile solutions to fabricate well-defined 3D structures. RSC Advances 2014, 4, 45504-45516, 10.1039/c4ra06892k.

- Kytai Truong Nguyen; Jennifer L. West; Photopolymerizable hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 4307-4314, 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00175-8.

- Andrit Allushi; Ceren Kütahya; Cansu Aydogan; Johannes Kreutzer; Gorkem Yilmaz; Yusuf Yagci; Conventional Type II photoinitiators as activators for photoinduced metal-free atom transfer radical polymerization. Polymer Chemistry 2017, 8, 1972-1977, 10.1039/C7PY00114B.

- Stephanie J. Bryant; Charles R. Nuttelman; Kristi S. Anseth; Cytocompatibility of UV and visible light photoinitiating systems on cultured NIH/3T3 fibroblasts in vitro.. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition 2000, 11, 439-457, 10.1163/156856200743805.

- Benjamin D. Fairbanks; Michael Schwartz; Christopher N. Bowman; Kristi S. Anseth; Photoinitiated polymerization of PEG-diacrylate with lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate: polymerization rate and cytocompatibility. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6702-7, 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.055.

- Stephan Benedikt; Jieping Wang; Marica Markovic; Norbert Moszner; Kurt Dietliker; Aleksandr Ovsianikov; Hansjörg Grützmacher; Robert Liska; Highly efficient water-soluble visible light photoinitiators. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry 2015, 54, 473-479, 10.1002/pola.27903.

- Georgina Müller; Michal Zalibera; Georg Gescheidt; Amos Rosenthal; Gustavo Santiso-Quiñones; Kurt Dietliker; Hansjörg Grützmacher; Simple One-Pot Syntheses of Water-Soluble Bis(acyl)phosphane Oxide Photoinitiators and Their Application in Surfactant-Free Emulsion Polymerization. Macromolecular Rapid Communications 2015, 36, 553-557, 10.1002/marc.201400743.

- Paola Occhetta; Roberta Visone; Laura Russo; Laura Cipolla; Matteo Moretti; Marco Rasponi; VA-086 methacrylate gelatine photopolymerizable hydrogels: A parametric study for highly biocompatible 3D cell embedding. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2014, 103, 2109-2117, 10.1002/jbm.a.35346.

- Seda Kızılel; Victor H. Perez-Luna; Fouad Teymour; Seda Kizilel; Photopolymerization of Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Diacrylate on Eosin-Functionalized Surfaces. Langmuir 2004, 20, 8652-8658, 10.1021/la0496744.

- Elbadawy A. Kamoun; Andreas Winkel; Michael Eisenburger; Henning Menzel; Carboxylated camphorquinone as visible-light photoinitiator for biomedical application: Synthesis, characterization, and application. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2016, 9, 745-754, 10.1016/j.arabjc.2014.03.008.

- R. R. Batchelor; G. Kwandou; Patrick T. Spicer; Martina H. Stenzel; (-)-Riboflavin (vitamin B2) and flavin mononucleotide as visible light photo initiators in the thiol–ene polymerisation of PEG-based hydrogels. Polymer Chemistry 2017, 8, 980-984, 10.1039/C6PY02034H.

- Sajjad Dadashi-Silab; Cansu Aydogan; Yusuf Yagci; Shining a light on an adaptable photoinitiator: advances in photopolymerizations initiated by thioxanthones. Polymer Chemistry 2015, 6, 6595-6615, 10.1039/C5PY01004G.

- Maximilian Tromayer; Ágnes Dobos; Peter Gruber; Aliasghar Ajami; Roman Dědic; Aleksandr Ovsianikov; Robert Liska; A biocompatible diazosulfonate initiator for direct encapsulation of human stem cells via two-photon polymerization. Polymer Chemistry 2018, 9, 3108-3117, 10.1039/c8py00278a.

- Han Young Woo; Janice W. Hong; Bin Liu; Alexander Mikhailovsky; Dmitry Korystov; Guillermo C. Bazan; Water-Soluble [2.2]Paracyclophane Chromophores with Large Two-Photon Action Cross Sections. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2005, 127, 820-821, 10.1021/ja0440811.

- Bruce A. Reinhardt; Lawrence L. Brott; Stephen J. Clarson; Ann G. Dillard; Jayprakash C. Bhatt; Ramamurthi Kannan; Lixiang Yuan; Guang S. He; Paras N. Prasad; Highly Active Two-Photon Dyes: Design, Synthesis, and Characterization toward Application. Chemistry of Materials 1998, 10, 1863-1874, 10.1021/cm980036e.

- Thomas Weiß; Gerhard Hildebrand; Ronald Schade; Klaus Liefeith; Thomas Weiß; Two-Photon polymerization for microfabrication of three-dimensional scaffolds for tissue engineering application. Engineering in Life Sciences 2009, 9, 384-390, 10.1002/elsc.200900002.

- Aleksandr Ovsianikov; Andrea Deiwick; Sandra Van Vlierberghe; Peter Dubruel; Lena Möller; Gerald Dräger; Boris Chichkov; Laser Fabrication of Three-Dimensional CAD Scaffolds from Photosensitive Gelatin for Applications in Tissue Engineering. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 851-858, 10.1021/bm1015305.

- Xiaojun Wan; Yuxia Zhao; Jianqiang Xue; Feipeng Wu; Xiangyun Fang; Water-soluble benzylidene cyclopentanone dye for two-photon photopolymerization. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2009, 202, 74-79, 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2008.10.029.

- Zhiquan Li; Jan Torgersen; Aliasghar Ajami; Severin Mühleder; Xiao-Hua Qin; Wolfgang Husinsky; Wolfgang Holnthoner; Aleksandr Ovsianikov; Jürgen Stampfl; Robert Liska; et al. Initiation efficiency and cytotoxicity of novel water-soluble two-photon photoinitiators for direct 3D microfabrication of hydrogels. RSC Advances 2013, 3, 15939, 10.1039/c3ra42918k.