1. Background

Neuroblastoma (NB) is a malignant pediatric solid tumor that originates during embryonic or early post-natal life from the sympathetic cells derived from the neural crest [

1]. NB is the most common extracranial tumor occurring in childhood [

2]; over 30% of cases are diagnosed in infants and the remaining, mostly, under five years of age [

3]. NB is characterized by remarkable heterogeneity, in terms of phenotype and localization. It can arise in several areas of the body: most of the cases develop in the abdominal region, especially from the adrenal glands, but can also develop in the chest, neck or along the spinal cord [

2]. Due to its complexity and heterogeneity, NB can show extremely different clinical behavior.

Several genomic alterations have been identified in NBs leading to different patterns of clinical behavior. Historically, NB subtypes were classified into different stages based on multiple factors such as genetic alterations, age of patient, presence of metastasis, etc. Stages 1, 2 and 4S described tumors with little or no risk and favorable prognosis. Instead, stages 3 and 4, known as high-risk NBs (HR-NBs), are characterized by aggressiveness, low response to therapy and poor prognosis [

4,

5].

Recently, a new NB classification was proposed by Ackermann et al. [

6] who found that alterations in telomere maintenance mechanisms as well as in RAS or p53 pathways better discriminate between high-risk or low-risk NBs than the previous classification. Telomeres are responsible for genomic integrity in normal cells, and telomere length and telomerase activity are crucial for cancer initiation and tumor survival. In particular, Ackerman et al. showed that survival rates were lowest for NB patients whose tumors harbored telomere maintenance mechanisms in combination with

RAS and/or

p53 mutations. On the other hand, low-risk NBs did not show telomere maintenance mechanisms, in the absence of which the possible mutations in

RAS or

p53 genes seem to not affect patient outcome [

6].

A clear example of neuroblastoma heterogeneity is the different clinical outcomes, ranging from spontaneous regression or differentiation into a benign ganglioneuroma to unremitting and aggressive progression despite multimodal therapy [

7]. The mechanisms underlying the spontaneous regression are currently unknown, and a better understanding of this process may help to identify new therapies.

The real etiology of this tumor is still unknown, but the sporadic form represents most of the cases, whereas only 1–2% of affected children present a genetic autosomal dominant inheritance pattern [

8]. NB can show a broad range of chromosomal abnormalities, but the most common genetic alteration is the amplification of the oncogene

MYCN, which is observed in 20–25% of cases and in 50% of high-risk tumors [

9]. Another genetic aberration, found in 9% of primary NB, is the activation of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (

ALK) gene [

3]. All these mutations are associated with poor clinical outcome, but, in a few cases, they represent possible therapeutic targets.

Important molecules used for NB therapy act on the membrane targets GD2 and B7-H3. GD2 is a disialoganglioside expressed on the membrane of numerous cancer cells, such as brain tumors, retinoblastoma, osteosarcoma and NB [

10]. Anti-GD2 monoclonal antibodies are currently used in therapy to improve standard treatments for HR-NBs, but further studies are necessary to confirm the effectiveness of this immunotherapy and to optimize it [

11]. However, in 12% of patients with bone marrow relapse, NB cells lose GD2 expression, thus rendering the use of this treatment impossible [

12]; for this reason, Dondero et al. [

13] developed a multiparametric flow cytometry to observe GD2 surface expression, suggesting B7-H3 targeting therapy for those patients in which GD2 is missed. B7-H3 is a transmembrane glycoprotein overexpressed in NB cells (particularly in bone marrow aspirates) [

14], as well as in melanomas, gliomas and breast and pancreatic cancers [

15]. B7-H3 is a member of the B7 family that may down-regulate natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity through binding to NK receptors, leading to the activation of inhibitory signals. Recently, a murine IgG1 antibody against B7-H3 (omburtamab) was tested for NB therapy, showing significant effectiveness in NB patients with central nervous system involvement [

15]. A phase II/III study is still ongoing [

16].

Despite the therapeutic approach advancement in recent years, NB still represents 15% of all pediatric cancer deaths [

17], and a comprehensive and detailed view of molecular and genetic mechanisms that bring to NB development is not available yet. For this reason, NB represents a significant unmet medical need and a challenge in terms of prevention and treatment, highlighting the importance of exploring new molecular pharmacological targets, such as non-coding RNA, especially for HR-NBs.

Over the past decades, it has become evident that the non-coding portion of the genome plays a fundamental role in many diseases and in cancer in particular. Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are functional transcripts that regulate gene expression at a transcriptional and post-transcriptional level. ncRNAs are classified as housekeeping RNAs (such as rRNA, tRNA) and regulatory RNAs such as microRNA (miRNA), piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA) and long non-coding RNA, which differ in terms of length [

18]. While lncRNAs are longer than 200 nucleotides, miRNAs are approximately 22 nucleotides in length. Recently, circular RNAs (circRNAs) have been also identified as gene regulators; their circular structure is due to the linkage between 3′ and 5′ ends of a single-stranded RNA molecule [

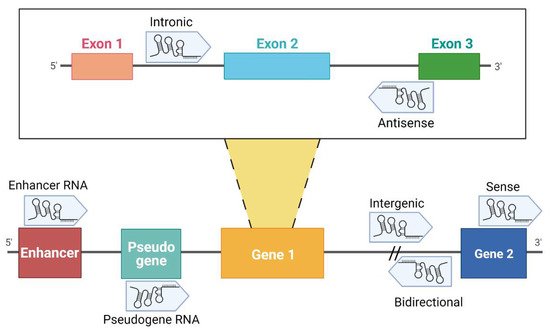

18]. A division of lncRNAs is reported in .

Figure 1. Classification of lncRNAs according to their genome localization. Intronic: the sequence originates from an intron region of a protein-coding gene [

19]. Antisense: transcribed from the antisense strand of a gene sequence, originating from an exon or intron region [

20]. Enhancer RNA (eRNA): RNA transcribed from transcriptional enhancer. eRNAs could present polyadenylation and 5′ cap. Generally, they are unstable with a short half-life [

21,

22,

23]. Pseudogene RNA: the transcripts originated from pseudogene and could be short or long ncRNAs [

24,

25]. Intergenic: the localization is in an intergenic region, precisely more than 1 kb away from closest genes [

20,

22,

26]. Bidirectional: the sequence is mainly located on the opposite strand with respect to a gene, of which transcription starts less than 1000 bp away [

26,

27,

28]. Sense: this kind of lncRNA is transcribed from the sense strand and contains exons of protein-coding genes [

29]; some are variants of mRNAs, while others do not contain a functional open reading frame [

28]. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 9 April 2021).

Despite the biological functions of many ncRNAs still being largely unknown, lncRNAs have been shown to be potentially involved in multiple cancer types [

23,

30,

31], including NB [

8,

32,

33]. Over the last year, high-throughput approaches became a powerful tool to identify a pool of lncRNAs that are differentially expressed by NB cells.