Hypophosphatasia (HPP) is a rare genetic disease characterized by a decrease in the activity of tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase (TNSALP). TNSALP is encoded by the ALPL gene, which is abundantly expressed in the skeleton, liver, kidney, and developing teeth. HPP exhibits high clinical variability largely due to the high allelic heterogeneity of the ALPL gene. HPP is characterized by multisystemic complications, although the most common clinical manifestations are those that occur in the skeleton, muscles, and teeth. These complications are mainly due to the accumulation of inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) and pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP).

- hypophosphatasia

- TNSALP

- pyridoxal-5′-phosphate

- asfotase alfa

1. Prevalence of HPP

2. The Enzyme

3. Genetics of HPP

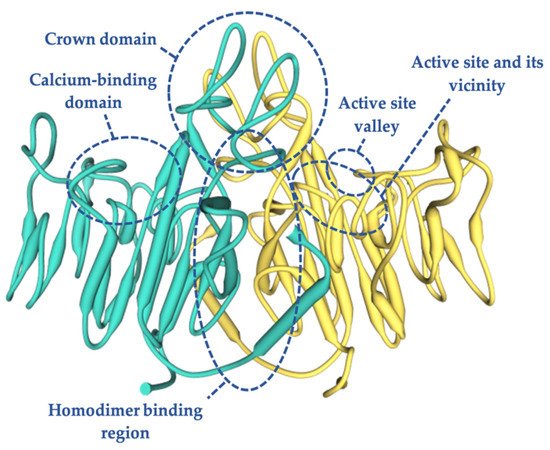

4. TNSALP Structure

5. Clinical Manifestations

6. Subtypes of HPP

6.1. Perinatal Lethal Hypophosphatasia

6.2. ”Benign Prenatal” Hypophosphatasia

6.3. Infantile Hypophosphatasia

6.4. Childhood-Onset Hypophosphatasia

6.5. Adult Hypophosphatasia

6.6. Odontohypophosphatasia

7. Diagnosis of HPP

Often, HPP patients are underdiagnosed or have a misdiagnosis, with years of HPP evolution until diagnosis [83]. This is because the common symptoms of this metabolic disorder, such as arthralgia, myalgia, and bone pain, are symptoms that are very similar to those that appear in rickets, imperfect osteogenesis, Paget’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, or fibromyalgia [22]: all of them with a higher prevalence than HPP. Therefore, a strong suspicion and great knowledge of the disease are necessary for diagnosis [84]. Another limiting factor for diagnosis is the low value assigned to a decrease in serum ALP activity, in contrast to the assessment that is usually made for an increase in the activity of this protein [55,84].

Clinical signs and/or symptoms are the first step for the diagnostic suspicion of HPP. However, there are clinical forms during the infant–adolescent period that can present with little or no clinical expression. In these cases, persistently low levels of serum ALP activity could indicate the existence of paucisymptomatic HPP, presenting greater clinical expressiveness in adults. Patients who present signs and/or symptoms at the musculoskeletal and/or dental level should be considered to have a suspected clinical diagnosis of HPP.

Respiratory and neurological symptoms that appear in the perinatal lethal and infant forms will strongly support the diagnostic suspicion [85]. The next step after clinical suspicion for the diagnosis of HPP should be the determination of ALP in the serum. Data from normal subjects show that bone ALP contributes approximately half of the total ALP activity in adults [86]. ALP activity that is persistently lower than the reference values may be associated with HPP. However, there are other clinical situations in which the activity of this enzyme is also decreased [86]. Knowledge of these secondary causes will be of great relevance when it comes to a correct diagnosis of the disease [85].

In addition to the more well-known causes of secondary hypophosphatemia, there are other less common situations that are also associated with low levels of ALP, and these must be considered to make an accurate diagnosis. Recent studies have shown that iron and ferritin are potent inhibitors of osteogenesis, significantly inhibiting ALP activity. This is attributed to the ferroxidase activity of ferritin as the central element of this inhibition. Consequently, hemochromatosis should be considered to be a secondary cause, different from HPP, leading to a decrease in ALP levels [87,88].

On the other hand, a few cases of patients affected by cleidocranial dysplasia, which can mimic HPP, have been described [89]. Cleidocranial dysplasia is a skeletal dysplasia caused by mutations in the bone/cartilage-specific osteoblast transcription factor RUNX2 gene. Although there are clinical manifestations that differ between both pathologies, these patients could present some of the radiographic and biochemical features of HPP. It is characterized by macrocephaly with persistently open sutures, absent or hypoplastic clavicles, dental anomalies, and delayed ossification of the pubic bones. Studies with RUNX2 knockout mice have shown a complete absence of ALP, suggesting that RUNX2 could participate in the regulation of TNSALP activity [90]. However, to date, it is not known whether this is a direct or indirect relation because there are no studies to identify the molecular mechanisms by which RUNX2 and TNSALP interact.

Additionally, mention should be made of the cases in which the clinical, radiological, and biochemical findings are typical of patients with infantile HPP, with the exception that serum ALP activity is normal or even increased [91,92]. This extremely rare phenotype is called “pseudohypophosphatasia” and has only been convincingly documented in two babies [46]. A possible explanation for these normal levels of ALP is the transient correction of hypophosphatasemia as a result of fractures or intercurrent diseases, or slight elevations in the levels of substrates of the enzyme that causes an overexpression of TNSALP [93,94].

Images compatible with osteopenia, chondrocalcinosis, and/or pathological fractures can be observed after carrying out radiological evaluation in patients affected by HPP. However, these are not pathognomonic findings for HPP [86]. The measurement of bone mineral density by Dual X Absorciometry (DXA) will support the diagnosis of HPP, but without being essential for it [85] since there are HPP-affected patients with a high risk of fragility fractures despite increased lumbar bone density determined by DXA [43]. In this context, it would be very useful to have studies evaluating bone architecture in patients with HPP to assess the contribution of trabecular and cortical bone to the risk of fractures in this population.

The clinical manifestations of HPP are due to the low activity of ALP, which leads to the accumulation of its natural substrates. These substrates are mainly PLP and PPi [23,55]. However, the best candidate for the study of enzyme functionality is PLP, due to the low accessibility for the determination of the substrate PPi. In children and adults affected by HPP, increased plasma levels of PLP are the biochemical marker that best correlates with the severity of the disease, this being the biochemical marker with the highest diagnostic sensitivity [2]. The positive and negative predictive value of PLP for the diagnosis of HPP in childhood is very high, although the absence of elevation of plasma PLP, or other substrates of TNSALP, cannot exclude the diagnosis of HPP [85]. Serum calcium and phosphate and urinary calcium values can also be elevated frequently in early forms of the disease. In general, the levels of PTH and vitamin D are within normal ranges [86].

The finding of pathogenic mutations in the ALPL gene allows the definitive diagnosis of HPP to be established. However, the diagnosis of HPP cannot be excluded by not finding a mutation in the ALPL gene. This is because the genetic study of ALPL is limited to the sequencing of coding regions of the gene (exons), without taking into account the promoter regions or intronic regions [7]. Furthermore, the regulation of the extracellular levels of PPi, responsible for some symptoms of HPP, is complex and involves several genes in addition to the ALPL gene [95].

Other studies have reported that there could be mutations in noncoding regions, such as the promoter or intergenic regions of the ALPL gene, which are not detected by Sanger sequencing. This could also explain the absence of mutations in this gene in patients with clinical and biochemistry compatible with HPP [96]. In this sense, whole ALPL gene sequencing, including the noncoding regions in patients of unclear cases, could be very useful to know if the patients are HPP-affected. There are other authors who postulate that in the face of a clear clinical suspicion (phenotype + radiology + laboratory findings), a genetic study is not essential for the diagnosis of HPP. However, this information is crucial to document hereditary patterns and the risk of recurrence, as well as for prenatal diagnosis [26,52].

8. Treatment of HPP

The approaching of HPP must be multidisciplinary and individualized based on the clinical manifestations being the treatment of related symptoms, the measure most used [84]. In perinatal lethal HPP, the patient may develop pulmonary hypoplasia, requiring respiratory support to control respiratory failure [55,63].Different therapeutic approaches with disparate results are described in the literature.

Bone marrow transplantation in infants has been tried with satisfactory results [103,104], while growth hormone therapy in children with HPP has also shown a significant increase in ALP activity and increased growth [105,106].

The clinical manifestations secondary to the deposition of calcium pyrophosphate or hydroxyapatite crystals respond to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or to glucocorticoids locally [84]. In addition, the use of cycles of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs gives good results for persistent pain secondary to fractures [72,107].

Another therapeutic approach would be the use of PTH or monoclonal anti-sclerostin antibodies. PTH’s mechanism of action is based on the direct stimulation of bone formation [108]. Isolated cases of HPP treated with teriparatide (PTH 1–34 or PTH 1–84) at low doses have been described as inducing with a “paradoxical reaction” [85], with decreased pain, better radiological consolidation of pseudofractures or stress fractures [109–111], and an improvement in biochemical and densitometric parameters [112]. However, cases have also been described in which the response to teriparatide treatment may vary depending on the TNSALP mutation [113–115]. An increase in ALP values, a decrease in PLP concentration, and an increase in lumbar bone mineral density (BMD) have also been observed with teriparatide treatment, with stability of femoral BMD [112]. Monoclonal anti-sclerostin antibody treatment has been demonstrated to increase bone formation and reduce bone resorption, increasing the BMD in HPP patients [116].

The use of calcium and/or vitamin D3 supplementation is not recommended in HPP-affected patients with normal calcium levels because it could cause hypercalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hypercalciuria [85].

It is important to note that bisphosphonate treatment in adults with HPP may increase fracture risk [74,117,118], since these are analogues of PPi and therefore contributing to the inhibition of hydroxyapatite formation.

Several enzyme replacements therapies have been evaluated to treat HPP. Among them, the use of the transfusion of blood plasma rich in TNSALP has been used. However, biochemical, clinical, and radiological improvement was only observed in some patients, but transiently and with nonreproducible results. This appears to be because the treatment is effective only if the TNSALP is incorporated into the bone structure [85].

The enzyme replacement therapy that has shown the greatest effectiveness to date is recombinant human TNSALP (asfotase alfa). It is a protein formed by the catalytic domain of TNSALP, the Fc fragment of IgG1, and a deca-aspartate motif that increases the affinity for its binding to hydroxyapatite [63]. The first results of the therapeutic study with asfotase alfa in 2012 in patients with severe HPP of the perinatal lethal or infantile forms demonstrated a significant improvement in skeletal, muscular, pulmonary, and cognitive and motor development. A rapid decrease in plasma levels of PLP and PPi was also observed [63]. However, some therapy-related adverse events have been reported, the most frequent being a local reaction at the subcutaneous injection site. Likewise, other side effects such as kidney, cornea, and conjunctiva calcifications have been reported in up to 55% of the juvenile-onset cases, without any change reported in vision or in renal function [5].

Recent studies have shown the effectiveness of asfotase alfa treatment in adults and adolescents with pediatric-onset HPP, showing an improvement of osseous consolidation of non-unions [119], a normalization of circulating TNSALP substrate levels, and improved functional abilities and health-related quality of life [119–121], without severe adverse events.

Treatment with asfotase alfa requires the correct therapeutic monitoring, both to adjust the dose and to control possible adverse effects. In addition, the appearance of ectopic mineralization should be monitored, maintaining radiological, renal ultrasound, and ophthalmological controls [122].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22094303