The cellular mechanisms of drug resistance prevent the correct efficacy of the therapies used in various types of cancer and nanotechnology has been postulated as a possible alternative to avoid them. This review focuses on describing the different mechanisms of drug resistance and dis-covering which nanotechnology-based therapies have been used in recent years to evade them in colon (CRC) and pancreatic cancer (PAC). Here we summarize the use of different types of nanotechnology (mainly nanoparticles) that have shown efficacy in vitro and in vivo in preclinical phases, allowing future in-depth research in CRC and PAC and its translation to future clinical trials.

- drug resistance

- colon cancer

- pancreatic cancer

- nanomedicine

- cancer stem cells

1. Introduction

According to the latest epidemiological data, colorectal cancer (CRC) and pancreatic cancer (pancreatic adenocarcinoma or PAC) rank third and eleventh in cancer incidence worldwide, respectively. In terms of cancer mortality, they are the second and seventh leading causes, respectively. Despite its low incidence, PAC has the highest mortality rate of all cancers, with a 5-year survival rate of only 9% [1,2]. On the other hand, CRC has a better prognosis in the initial stages of the disease, but in stage IV (i.e., metastatic) its mortality is also very high, with 5-year survival rates of only 13% [3]. In both PAC and stage IV CRC, current therapies only result in a slight increase in survival, mainly due to the phenomenon of drug-resistance.

Drug-resistance can be classified into innate or acquired (generated after treatment) [4]. Innate resistance usually results from pre-existing mutations in genes involved in cell growth or apoptosis [5]. For instance, the p53 mutation abolishes the function of this protein, facilitating resistance to standard medications used in colon and pancreatic tumors, such as gemcitabine (GEM) (antimetabolites), doxorubicin (DOX) (anthracyclines), or cetuximab (EGFR-inhibitor) [6]. Genes involved in DNA repair systems (e.g., MMR) may be altered in these tumors [7]. These systems are responsible for failure to standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)/oxaliplatin (OXA) and 5-FU-based adjuvant chemotherapy [8]. Another source of innate resistance is the activation of cellular pathways involved in the elimination of toxic elements or in damage prevention. These pathways can be exploited by tumor cells to protect themselves from anti-tumor drugs [5]. Examples of these are the transporter pumps, such as the ATP binding cassette (ABC) family members, including MDR1 or P-glycoprotein-P-GP- (ABCB1), Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 1 (MRP1) and Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 3 (MRP3) or Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP), which promote drug transport outside the cell in tumor pathology [9]. These existing pathways also include DNA repair enzymes such as poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1), which allows cells to survive the DNA damage caused by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, thus promoting drug resistance [10]. PARP-1 inhibition has been linked to the better response to therapy in various cancers, including PAC [11]. Finally, another source of innate resistance lies in the heterogeneity of the tumor, which may contain pre-existing cell subpopulations insensitive to treatment, including cancer stem cells (CSCs). Numerous trials have demonstrated the importance of CSCs in tumor resistance, since these cells are selected after chemo and radiotherapy [12], and may be resistant even to novel therapies, such as immunotherapy.

The resistance developed after antitumor treatment is known as acquired resistance and causes a gradual reduction of the anticancer efficacy of drugs. This resistance may result from the development of new mutations (which may affect new proto-oncogenes or modify treatment targets) or from alterations in the tumor microenvironment (TME) during treatment, leading to decreased antitumor efficacy of drugs. An example of modification of the treatment targets are mutations of the EGFR ectodomain, which have been shown to generate secondary resistance to anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (i.e., rituximab) in CRC [13,14]. Regarding TME-related acquired resistance, the TME promotes the survival and migration of cancer cells, conferring resistance to chemo, radio and immunotherapy treatments [15]. In sum, resistance phenomena involve complex and diverse resistance mechanisms that can occur simultaneously during tumor development and treatment. Therefore, it is essential to search for new therapeutic alternatives to overcome these mechanisms.

Nanomedicine is based on the use of nanomaterials, taking advantage of their different physicochemical properties to develop innovative applications in the field of medicine. The use of these materials has allowed significant improvements in antitumor treatment through the generation of nanoparticles (NPs) capable of transporting and releasing the drug in tumor cells more efficiently. In addition, NPs can be conjugated with different ligands on their surface to specifically damage tumor cells and reduce drug toxicity in healthy tissues [16]. Remarkable advantages of these molecules include their ability to passively accumulate in tumors via enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, which results from increased disorganization of the vasculature and impaired lymphatic drainage of tumors, and their stability in blood due to improvements such as pegylation [17].

2. Increased Efflux of Drugs

2.1. Efflux Pump P-Glycoprotein and Drug Resistance

One of the most relevant resistance mechanisms of cancer cells is P-GP, a membrane protein which pumps out the drugs from the inside of cells to the extracellular space, reducing their therapeutic effect [18]. This protein, also known as ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1 (ABCB1) or ABC transporters, comprises a superfamily of efflux pump proteins with different members that may be involved in the MDR phenotype of tumor cells. In addition to P-GP, other members from this superfamily play an important role in the MRD phenotype in CRC and PAC, such as MDR-associated proteins (MRPs/ABCCs) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) [9,19] and MDR1 [20,21]. P-GP is a 170 kD protein normally present in a variety of cells of the digestive system (e.g., common bile duct of the liver and pancreatic ducts), being highly expressed in the apical surface of epithelial cells [20]. However, the overexpression of P-GP in cancer cells is usually associated with a low therapeutic efficacy [22,23,24,25,26,27] especially in CRC. In this context, many nanoformulations have been designed to overcome the P-GP-mediated MDR phenotype in CRC and PAC (Table 1).

Table 1. Nanoformulations used to overcome the MDR phenotype mediated by efflux pumps in colorectal and pancreatic cancers.

| Nanoformulation | Drug/Cargo | Efflux pump | CRC/PC | Mechanism to overcome MDR | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold nanorod coated with three layers: mSiO2, PHIS and TPGS | DOX | P-GP | CRC | PHIS to escape the endocytic pathway and TPGS to inhibit P-GP | [28] |

| Liposomes loaded with ACF | DOX | P-GP | CRC | ACF inhibits HIF-1, leading to downregulation of P-GP in hypoxic environment | [29] |

| Hydrogel with PEG-coated gold nanorods and TPGS-coated PTX nanocrystals | PTX | P-GP | CRC | TPGS inhibits P-GP | [30] |

| Vitamin E succinate-grafted-chitosan oligosaccharide with RGD and TPGS | BU | P-GP | CRC | TPGS and BU inhibits P-GP | [31] |

| Lignin NPs functionalized with hyaluronic acid transporting quercetin | IRI | P-GP | CRC | Quercetin inhibits P-GP | [32] |

| Nanovectors derived from grapefruit lipids with the LA1 aptamer and siRNA | DOX | P-GP | CRC | Downregulation of P-GP expression | [33] |

| Microbubbles transformable into NPs for PDT and imaging | CPT | ABCG2 | CRC | Reduction of ABCG2 expression | [34] |

| PEG-PLGA NPs | SN38 | ABCG2 | CRC | Reduced mRNA expression level | [35] |

| Curcumin loaded in HP-β-CD | DOX | P-GP | CRC | Curcumin nanoformulation overcomes DOX resistance | [36] |

| Polymeric NPs with PEG and PEI | Ce6 | ABCG2 | PC | NPs reduce the ABCG2 efflux of Ce6 | [37] |

| pHPMA-b-pDMAEMA NPs | ODNs | P-GP | CRC | Decreased P-GP expression by modulation of NF-κB signalling pathway | [38] |

| Poly (aspartic acid) with TAT peptide and PEG | DOX | P-GP | CRC | Inhibition of P-GP efflux activity by size exclusion-effect | [39] |

| Nanomicelles with SMA | PTX | P-GP | CRC | Enhance of drug antitumor effect with oral administration | [40] |

| Liposomes for PDT with benzoporphyrin derivate | IRI | ABCG2 | PC | Sinergy of PDT and IRI: PDT reduces the efflux of ABCG2 | [41] |

| PLGA NPs functionalized with Pluronic F127 and chitosan | CPT | P-GP | CRC | Pluronic F127 and chitosan downregulate MDR1 expression | [42] |

| Liposomes coated with hyaluronic acid | Imatinib mesylate | P-GP | CRC | Nanosystem P-GP modulation | [43] |

| Pegylated liposomes | ASOs and/or EPR | MDR1, MRP1, MRP2 | CRC | Reduced expression of MDR1, MRP1 and MRP2 | [44] |

| Hybrid lipid NPs with AL-HA polymer | IRI | P-GP | CRC | Disruption of ATPase activity and reduction of MDR1 gene expression | [45] |

| Inactive phenolato–titanium (IV) complexes | - | P-GP | CRC | Same toxicity in sensitive and resistant tumor cells | [46] |

| Liposomes functionalized with specific phage fusion proteins | DOX | P-GP | PC | Same drug accumulation in tumor cells in presence and absence of verapamil | [47] |

| Liposomes | NitDOX | P-GP, MRP1 | CRC | Efflux activity reduction by nitration of P-GP and MRP1 with NO released by NitDOX | [48] |

| Liposomes with PEG | PTX | P-GP | CRC | Similar antitumor activity in vivo between mice bearing resistant tumor and non-resistant tumor | [49] |

| NPs of PEG-PLA functionalized with K237 peptide | PTX | P-GP | CRC | NPs target endothelial cells for antiangiogenic and antitumor activity in resistant tumors | [50] |

| Pegylated liposomes | ASOs and/or EPR | P-GP, MRP1,MRP2 | CRC | Similar antitumor activity in resistant and non-resistant tumors | [51] |

| PLGA NPs and liposomes | GEM | NS | PC | Increase in GBC cytotoxicity in resistant tumor cell lines | [52] |

| Anionic liposomal NPs | DOX | P-GP | CRC | Nanosystems change the amount of P-GP lipid rafts and inhibit efflux activity (glycine 185) | [53] |

| PRA nanodrug coated with hyaluronic acid | - | P-GP | CRC | Generation of holes in resistant cells makes them more sensitive to DOX | [54] |

Mesoporous silica (mSiO2); pH responsive polyhistidine (PHIS); acriflavine (ACF); hypoxia-inducible-factor-1α (HIF-1α); d-α-tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (TPGS); doxorubicin (DOX); P-glycoprotein (P-GP); colorectal cancer (CRC); pancreatic cancer (PAC); photothermal therapy (PTT); poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA); nanoparticles (NPs); verapamil (VER); polyethylene glycol (PEG); paclitaxel (PTX); arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD); bufalin (BU); hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HP-β-CD); polyethylenimine (PEI); chlorin e6 (Ce6); ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 2 (ABCG2); NF-κB decoy oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs); photodynamic therapy (PDT); poly[N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide]-poly(N,N-dimethylaminoethylmethacrylate) (pHPMA-b-pDMAEMA); antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs); camptothecin (CPT); epirubicin (EPR); alendronic acid and hyaluronic acid (AL–HA); irinotecan (IRI); nitric oxide-releasing DOX (NitDOX); polyethyleneimine/all-trans retinoic acid conjugates (PRA); poly(styrene-co-maleic acid) (SMA); gemcitabine (GEM); not specified (NS).

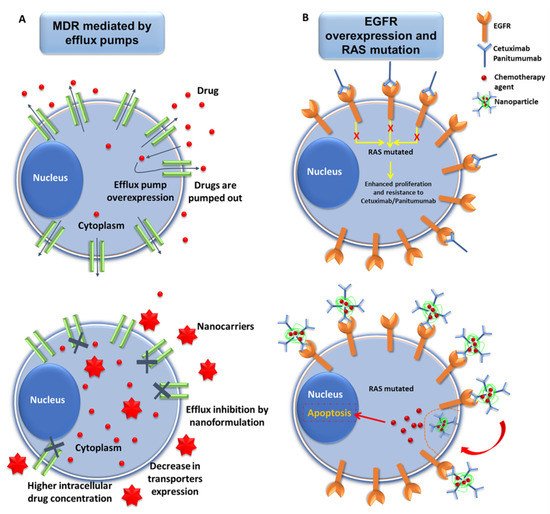

Despite the fact many P-GP inhibitors have been developed (e.g., verapamil, tariquidar, 11C-laniquidar, natural alkaloids or herbal natural products) [55,56,57,58,59], most of them showed significant limitations (systemic toxicity, insolubility, short blood half-life or rapid metabolization) [21,58,60,61]. The use of nanoformulations could overcome these drawbacks (Figure 1A). Recently, bufalin (BU), an antitumor drug that blocks P-GP-mediated resistance in CRC [62], was associated with vitamin E succinate-grafted-chitosan oligosaccharide with RGD peptide (arginine-glycine-aspartic acid) and TPGS. Compared to free BU, this combination showed improved antitumor activity (43% tumor volume reduction), pharmacokinetic profile and toxicity in resistant-CRC (LoVo/ADR cells)-bearing nude mice [31]. Moreover, the nanoformulation alone (i.e., without P-GP inhibitors) can overcome the P-GP-mediated MDR. For instance, treatment of PANC-1, a PAC cell line that overexpresses P-GP with DOX-loaded liposomes modified with phage fusion proteins for specific targeting, showed similar drug accumulation in presence and absence of verapamil [63,64]. Accordingly, this nanoformulation avoided P-GP-mediated expulsion and increased cytotoxicity of DOX (IC50 10-fold lower) [47]. Pan, et al. [65] overcame MDR mediated by P-GP in HCT8/ADR resistant cells using a large nanoformulation consisting of DOX-loaded poly(aspartic acid) NPs functionalized with TAT peptide and PEG, which is not a substrate of the efflux pump. In other cases, multifunctional NPs that combine several strategies at the same time to overcome the MDR phenotype have been used. For example, DOX-loaded gold nanorods coated with mesoporous silica (mSiO2) used in CRC photothermal therapy (PTT) and chemotherapy have been improved by using pH-responsive polyhistidine (PHIS) and D-α-tocopherol PEG 1000 succinate (TPGS) to induce endocytic pathway escape and to inhibit P-GP, respectively [28]. These nanorods showed excellent results in male athymic nude mice bearing SW620/Ad300 cells, achieving a significant reduction in tumor volume (~3-fold) with low systemic toxicity. Interestingly, resistant CRC has also been treated with local PTT using gold nanorods coated with PEG and paclitaxel (PTX) nanocrystals coated with TPGS (all of them combined into a hydrogel). Promising results were obtained in the SW620/Ad300 cell line in vitro (~178-fold decrease in the IC50 of PTX) and in male athymic nude mice bearing SW620/Ad300 tumors [30]. The use of phosphatidylserine (PS) lipid nanovesicles with encapsulated PTX showed a synergistic effect against the chemoresistant HCT15 cell line overexpressing the MDR1 gene product P-GP, both in vivo an in vitro. These NPs induced cell cycle arrest at G2/M phase, downregulated ki-67, Bcl-2, and CD34, upregulated caspase 3, reduced the systemic toxic effects of PTX and no inflammatory response was reported [66].

Figure 1. Representative scheme of nanomedicine strategies against drug resistance in pancreatic cancer. (A) Interactions of nanoformulations with MDR mechanism in pancreatic cancer (PAC) cells. Drugs carried by NPs may overcome MDR mechanisms of PAC cells mediated by efflux pumps via the inhibition of drug efflux, decrease in the expression of the transporter proteins, and increased accumulation of drug inside the tumor cells. (B) Exploiting the overexpression of EGFR to overcome resistance mediated by RAS mutations in PAC cells. PAC cells overexpress EGFR, which can be targeted by NPs conjugated with mAbs (Cetuximab/Panitumumab) (see below). This enables increased internalization of the chemotherapy drugs, thus leading to cellular apoptosis, even in RAS-mutated cancer cells.

2.2. Other Efflux Pumps

Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2), also known as mitoxantrone resistance protein (MXR) or placenta ABC protein (ABC-P), is a small member of the ABC superfamily (~75 KDa) with a more limited number of substrates (e.g., amptothecin [CPT], tyrosine kinase inhibitors and methotrexate) and inhibitors (e.g, imatinib or poloxamines) compared to P-GP [67]. Although BRCP/ABCG2 is usually highly expressed in hematological cancers, it has also been found to be overexpressed in CRC and PAC [68,69]. In fact, 72% of pancreatic cell lines from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) overexpressed this protein [69]. Nanoformulations such as irinotecan-loaded liposomes with benzoporphyrin derivative for photodynamic therapy (PDT) were able to overcome ABCG2-mediated resistance, decreasing tumor volume from 70% to 25% in mice bearing pancreatic tumors [41]. PDT has also been used with polymeric NPs with PEG and polyethylenimine (PEI) in pancreatic cells with variable expression levels of ABCG2 (+AsPC-1 and -MIA PaCa-2 and induced +MIA PaCa-2), increasing the intracellular concentrations of the photosensitizer through reduction of its efflux by ABCG2 [37]. On the other hand, pegylated poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) NPs with verapamil and SN38 (active form of CPT) showed no significant differences in drug cytotoxicity in HT29 CRC cells, but a significant decrease in ABCG2 mRNA expression (2.277-fold) in comparison with the free drug (4.793-fold) was observed [35]. In addition, microbubbles containing porphyrin/CPT-floxuridine for chemotherapy, PDT and imaging, generated NPs suitable for tumor therapy after exposure to ultrasound. This treatment significantly reduced the expression of ABCG2 in HT29 cells by increasing the concentration of CPT, inducing an in vivo growth inhibition (90%) of the tumor without recurrence [70].

On the other hand, the MRP1/ABCC1 and MRP3/ABCC3 proteins, which have a similar molecular weight (~190 KDa) and structure, contain a different n-terminal region in relation to P-GP [71,72,73]. Drug substrates of MRP1 and P-GP are similar except for taxanes, which are only P-GP substrates [73]. The spectrum of molecules transported by MRP3 is limited [74] In fact, MRP1 is the protein mostly involved in the therapeutic failure resulting from MDR [75]. Some nanoformulations have been designed to specifically overcome efflux pumps, including MRP. Nitric oxide-releasing DOX (NitDOX) was loaded in liposomes to treat HT29 cells resistant to DOX mediated by MRP1 and P-GP. Nitration of both proteins significantly reduced their activity [48]. In addition, pegylated liposomes loaded with epirubicin and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) against MDR1, MRP1 and MRP2 increased the antitumor activity of the drug in mice bearing CRC (CT26 cells), while administration of ASOs alone did not show significant differences between resistant and non-resistant tumors [51].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers13092058