Embelin (2,5-dihydroxy-3-undecyl-1,4-benzoquinone) is an orange solid derived from berries of the Embelia ribes plant found throughout India and is not water soluble; however, it can dissolve in organic solvents. Embelin has shown excellent antioxidant activity when scavenging the superoxide radical.

- embelin

- HSV-1

- antiviral

- antioxidant

1. Introduction

Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1), a member of the family Herpesviridae, subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae, is an enveloped virus with a double-stranded (ds) DNA genome that causes a wide range of infections in humans from mild, uncomplicated mucocutaneous infections to life-threatening ones [1]. The dsDNA is enclosed within an icosahedral protein surrounded by a lipid bilayer [2]. HSV-1 has become a global health concern with 67% of the world population (estimated 3.4 billion) between the ages of 0 and 49 infected [3,4].

Entry of the virus to initiate lytic infection involves multiple surface glycoproteins [glycoprotein B (gB), glycoprotein C (gC), glycoprotein D (gD), glycoprotein H (gH), and glycoprotein L (gL)] interacting with surface receptors on the host cell. Specifically, gC and gB bind loosely to heparan sulfate proteoglycans followed by high-affinity binding of gD binding to entry receptors [5,6,7]. A number of cell receptors interact with gD. Some of these known receptors include the herpes virus entry mediator, nectin-1, and 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate [8,9]. This induces a conformational change leading to the formation of a fusion complex composed of gB, gH, and gL. The viral nucleocapsid and tegument are released into the cytoplasm [8]. There is evidence for an atypical method of endocytic entry not mediated by clathrin-coated pits or caveolae [10]. Following entry of the virus into the cytoplasm, the virus particles travel to the nucleus where the viral DNA enters through the nuclear pore complex, and the viral genome replicates and is transcribed [11]. Virions are assembled in the cytoplasm and released by lysing the infected cell. Upon release, these new virions are capable of infecting new host cells [12].

HSV-1 is the viral causative agent of genital and oral herpes. These contagious and long-lasting infections cause painful blisters or ulcers at the site of infection [13]. The virus enters a latent phase in sensory ganglia, preventing clearance by the immune system [2].

Acyclovir, a nucleoside analog, its derivatives and their respective prodrugs, valacyclovir and famciclovir, are effective treatments for HSV-1 infections [4,14]. Acyclovir triphosphate is a substrate for the viral DNA polymerase that terminates viral DNA synthesis [15]. The latent stage and the development of resistance present limitations to the use of these drugs [8,16]. Additionally, despite efforts through the years, there does not exist a successful vaccine [17,18]. Since the virus can remain latent, it can be reactivated at any time. It is important to continue to search for novel antiviral compounds due to the ability of the virus to develop resistance to therapeutics. Research has reported that many biological plant-based compounds have demonstrated antiviral activity against HSV-1 infections. Plant based compounds such as curcumin, resveratrol, pomegranate rind extract, Cornus canadensis extract, and extracts from Camellia sinensis (epigallocatechin gallate and its lipophilic modifications, and theaflavins) have demonstrated activity against HSV-1 infections [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Several studies have determined that polyphenols inhibit adsorption and penetration during the viral lytic cycle [23,25,26,27,28,29].

Induction of oxidative stress is a mechanism used by several viruses. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection results in the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediated by glycoprotein 120 [30] and Tat proteins [31]. Influenza A viruses induce oxidative stress mediated by an over-production of ROS [32,33]. This increase in ROS was accompanied by a reduction in the antioxidant glutathione [34] and an increase in virus titer [32]. Surface antigens of hepatitis B virus (HBV) were reported to mediate ROS production; increased endoplasmic stress was linked to higher ROS production [35,36]. Curcumin, a polyphenol, inhibited an enzymatic reaction of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1). Inhibition of APE1 redox function decreased cell proliferation [37,38]. Curcumin inhibited Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection and inhibited angiogenesis [38]. Treatment with direct acting antivirals was found to improve the circulating redox status of patients with chronic hepatitis C infections [39].

Embelin (2,5-dihydroxy-3-undecyl-1,4-benzoquinone) is an orange solid derived from berries of the Embelia ribes plant found throughout India and is not water soluble; however, it can dissolve in organic solvents. Embelin has shown excellent antioxidant activity when scavenging the superoxide radical [40].

Embelin has demonstrated many biological activities including anxiolytic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticonvulsant, antidepressant, anthelmintic, antimicrobial, and anticancer [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. Embelin has been studied as an antibacterial agent and was shown to be effective against Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, Shigella flexneri, Shigella sonnei and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [47]. A more recent study has shown that embelin provides promising antibacterial activity against some Gram-positive bacteria and bacteriostatic activity against Gram-negative ones [49]. Only minimal studies have been conducted to determine its antiviral properties. Extracts of Embelia schimperi (embelin and 5-O-methylembelin) inhibited infection of hepatitis C virus [50].

Embelin was found to have antiviral activity against influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) strain when applied directly to extracellular virions. In silico molecular docking analysis indicated that embelin interacts with the receptor binding domain of the viral hemagglutinin of influenza virus A [51]. Cell culture experiments combined with in silico docking analyses determined that embelin inhibited hepatitis B virus (HBV) by interacting with the HBV polymerase [52]. A recent computational study demonstrated the feasibility of covalent bond formation between embelin and the main protease of SARS-CoV-2, 3CLpro [53].

2. Cytotoxicity Study of Treatment of Vero cells with Embelin

3. Antiviral Effects of Embelin on HSV-1

3.1. Proliferation Assay of Vero Cells Infected with HSV-1 and Embelin Treated HSV-1

3.2. Viral ToxGlo ATP Detection Assay

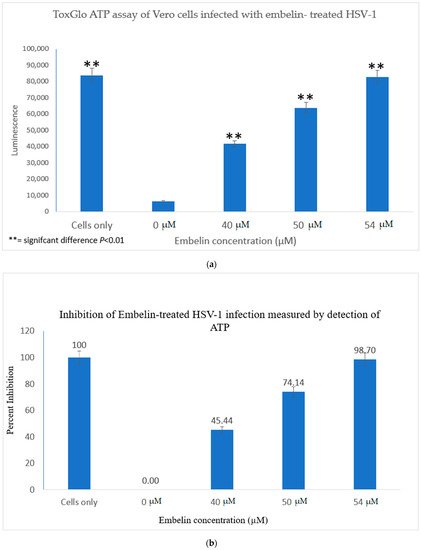

The Viral ToxGlo assay quantifies cellular ATP as a measure of metabolically active viable cells This assay measured the effect of treatment of HSV-1 with various concentrations of embelin. Cell viability was measured by luminescence (RLU) at 48 hpi and is shown in Figure 3a.

The results indicated that the RLU decreased significantly for the 0 µM concentration (untreated HSV-1 control). The embelin treated HSV-1 increased the RLU in a dose dependent manner. The RLU of the 54 µM treated sample was equivalent to the RLU of uninfected Vero cells. This illustrated that 54 µM embelin treated HSV-1 does not affect cell viability (Figure 3a). The Student T test indicated that there are significant differences in cell viability when Vero cells are infected with HSV-1 treated with concentrations of embelin ranging from 40 to 54 µM as compared to the Vero cells infected with untreated HSV-1 (p < 0.01).

The greatest percentage of inhibition was observed with the 54 μM treatment at over 98% inhibition followed by 74% inhibition at the 50 μM treated HSV-1. Percent inhibition, as measured by the ToxGlo ATP Detection assay is shown in Figure 3b.

4. Study of the Mechanisms of Embelin on HSV-1 Infective Cycle

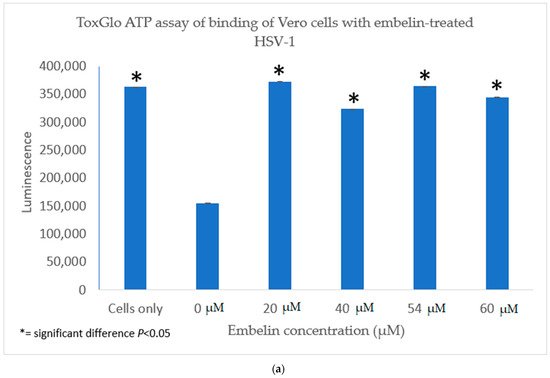

4.1. Inhibition of Binding by Embelin Treated HSV-1

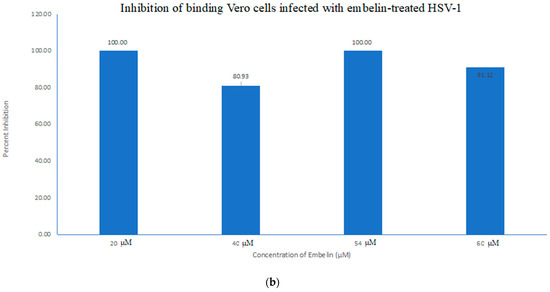

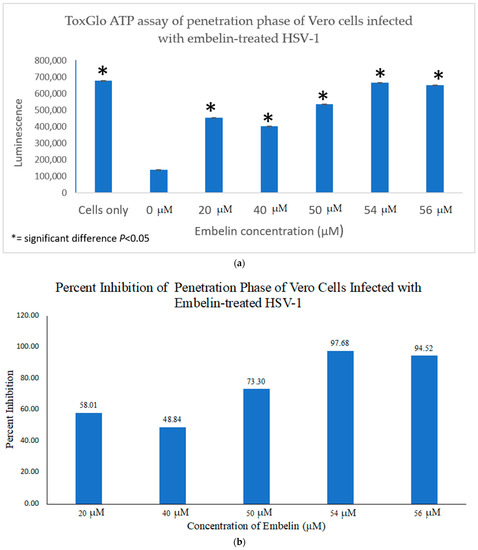

4.2. Inhibition of Penetration by Embelin Treated HSV-1

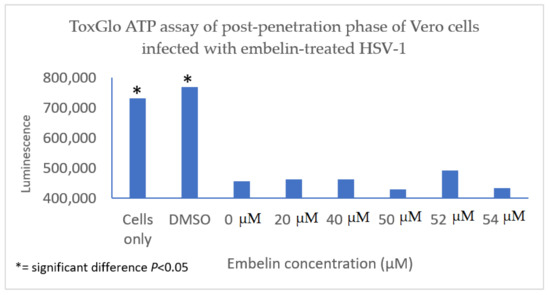

4.3. Inhibition of Post Penetration by Embelin Treated HSV-1

The antiviral effect of embelin on the post penetration step of the viral cycle was determined by infecting Vero cells with HSV-1 at 4 °C for 2 h to ensure attachment but not penetration of the HSV-1. Cells were then treated with embelin after the virus had entered the cells for 30 min at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cell viability was measured 48 hpi. The results indicated that treatment with embelin after adsorption and penetration did not affect HSV-1 infection. There is minimal difference in the values obtained with addition of various concentrations of embelin and amount of luminescence resulting from viral infection control (0 µM embelin) (Figure 8). This further suggested that embelin is able to inhibit early stages of the virus infection cycle but has no effect after the entry of HSV-1.

Figure 8. Treatment of HSV-1 infected cell with embelin post penetration does not affect cell viability. HSV-1 infected cells were treated with concentrations of embelin ranging from 20 µM to 54 µM post-penetration. DMSO represents the vehicle control up to 2% administration of DMSO. There is no significant difference in cell viability when HSV-1 infected cells are treated with embelin.

5. Discussion

One strategy that viruses use to manipulate host cell machinery in viral infections is modulation of the intracellular redox state. An imbalance of the redox state towards oxidant conditions is a key event during viral infections. Polyphenols are antioxidants that may protect cells against oxidative damage. This study explored the role of the antioxidant embelin as an antiviral agent against HSV-1 infection of cultured Vero cells. Embelin was determined to be non-cytotoxic to Vero cells at the concentrations tested. Treatment of virions with embelin resulted in increased cell proliferation and viability, inhibition of virus infection at the early stages of infection, and reduction in the levels of hydrogen peroxide, H2O2. H2O2 is a major redox metabolite that functions in redox sensing, signaling and regulation [57]. It occurs as a metabolite of oxygen in aerobic metabolism in mammalian cells [58]. HSV-1 infection of neural cells increased ROS levels as early as 1 hpi and ROS levels remained elevated at 24 hpi [59].

Infection of Vero cells with HSV-1 led to increased ROS levels in addition to decreased ATP in cells. Embelin effectively inhibited the cytotoxic effects of HSV-1 infection. The inhibitory effect of embelin may be attributed to its role as an antioxidant.

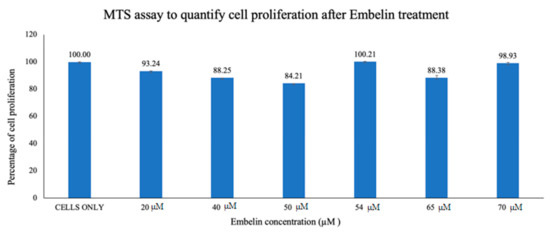

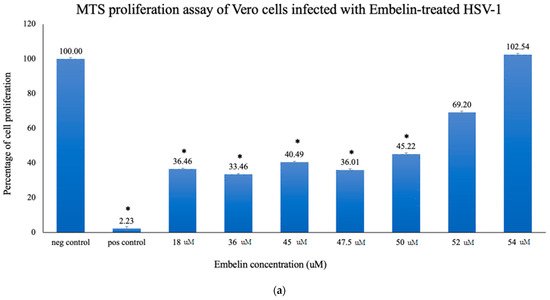

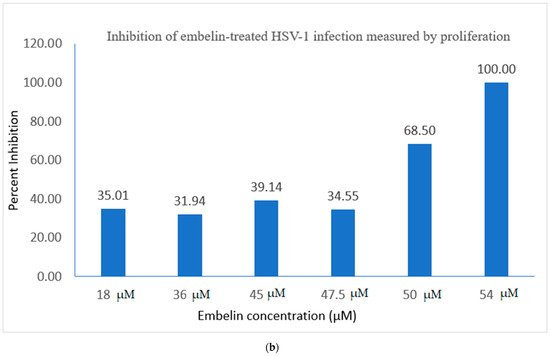

In this study it was determined that embelin has no toxic effects on the cell up to 70 μM (Figure 1). This finding aligned with previous studies that report embelin as a safe, non-cytotoxic compound [41,42,52]. We then treated the HSV-1 virions with embelin to observe the antiviral effects. Cell proliferation, an indicator of the cellular response to embelin treatment on HSV-1, infection was measured. Treatment of HSV-1 with embelin at concentrations ranging from 40–54 µM effectively inhibited infection. Treating the virus resulted in 102.5% cell viability as compared to uninfected cells (Figure 2a). When the percent inhibition was calculated, the percent inhibition was the highest at 54 μM calculated at 100% and 98.7%, respectively (Figure 2b and Figure 3b). Cell viability was also assessed by measuring the amount of ATP in infected cells (Figure 3a). The percent of inhibition, as determined by the detection of ATP, reached 98.7% when HSV-1 was treated with 54 µM concentration of embelin. Antiviral effects of embelin were observed using microscopy at an inhibitory concentration of 54 µM (Figure 4 and Figure 5). The antiviral effect of embelin was also demonstrated by the reduction in the synthesis of HSV-1 DNA (Figure 3).

We investigated the inhibitory mechanism of embelin. Treatment with embelin affected the early stage of HSV-1 infection of Vero cells, the efficacy of which may be due to the insertion of embelin in the Vero cell membrane [41]. Embelin, at concentrations ranging from 20 to 60 µM, inhibited the binding stage of HSV-1 infection (Figure 7a,b) and penetration at concentrations ranging from 20 to 56 µM (Figure 7a,b). The proposed antiviral mechanism of embelin is consistent with the action of other antivirals [23,25,26,27,28]. Additionally, this action may be attributed to the excellent antioxidant activity of embelin, when sequestering the superoxide radical [40,41].

Computational studies have revealed the mechanism by which quinone derivatives can inhibit SARS-CoV-2 {53]. Previous studies reported specific modes of action in the biological activities of embelin. Embelin inhibited the nuclear factor—κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway leading to suppression of NF-κB anti-apoptotic and metastatic gene products [60]. Embelin suppressed paraquat-induced lung injury through suppressing oxidative stress, inflammatory cascade, and MAPK/NF- κB signaling pathway [61]. As an anti-cancer agent, embelin suppressed the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT-3) pathway to suppress cell proliferation and invasion in cancer cells [62].

Viral infections result in oxidative cell damage due to disruption of cellular antioxidant mechanisms [63]. ROS levels increased in neural cells following HSV-1 entry and replication [59]. HSV-1 infection and oxidative stress have been linked to the neurodegeneration associated with Alzheimer’s disease [64]. Influenza A infection of cultured cells led to increased levels of ROS that correlated with an increase in virus titer [32]. Additionally, oxidative stress is involved in cellular damage associated with hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency co-infections and suggest that altered redox status promotes cellular damage [65]. Direct acting antivirals restored circulating redox homeostasis in patients affected with chronic hepatitis C infection [39]. Curcumin was found to be an inhibitor to APE1 (Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease1) redox function, affecting many genes and pathways. Curcumin inhibited Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) lytic replication [38]. We have shown that treatment with embelin reduced ROS caused by HSV-1 infection (Figure 9). Future studies are required to provide additional information on the therapeutic potential of embelin, such as determining the selectivity index required for drug development.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms9020434