Epigenetic modifications alter the gene function without changing the underlying DNA sequence. Negatively charged DNA is wrapped around positively charged histones forming a nucleosome, a simple chromatin unit. Chemical alterations to histone proteins include methylation and acetylation. These histone modifications can induce the formation of an open DNA state. The open state enables gene expression by allowing TFs and enzymes to bind to DNA. Alternatively, chromatin may acquire a closed heterochromatin state suppressing gene expression by inhibiting the initiation of transcript. These epigenetic modifications can be induced by various factors, including phytochemicals present in the diet. Epigenetic changes in gene function are heritable and are not attributed to alterations of the DNA sequence.

- Epigenetics

- Synucleinopathies

- DNA methylation

- phytochemicals

- histone modifications

1. Epigenetic Mechanism and Neurodegeneration

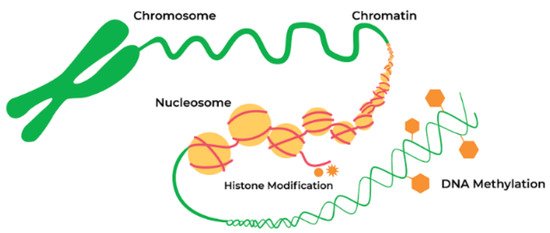

DNA methylation and post-translational modifications of nucleosomal histones (Figure 1) alter chromatin structure and regulate gene expression. The study of epigenetic regulation has many exciting translational aspects, one of which is analysis of association explaining the mechanisms linking gene and diet. Investigation in this field can elucidate the relationship between nutrition and neurodegenerative diseases. Changes in the epigenome may cause transcriptional alterations and genomic instability, thus contributing to the development of neurodegenerative diseases and other age-related disorders [1]. Growing evidence supports the hypothesis that various epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) are organized and coordinated, forming an “epigenetic network” [2].

2. Epigenetic Mechanisms in PD Pathogenesis

DNA methylation, histone modifications, and RNA-based mechanisms are the principal epigenetic mechanisms involved in PD pathophysiology (Figure 1). These biochemical processes regulate the expression of α–synuclein and other proteins involved in PD pathogenesis. One of the indirect proofs of the role of epigenetics in PD pathogenesis is the finding that DNA in PD patients has increased cytosine modifications, especially in genes responsible for neurogenesis, synaptic structure and neurodevelopment [3].

Figure 2. Epigenetic alterations are heritable and stable gene expression changes that occur through modifications in the chromosome rather than in the DNA sequence. Epigenetic mechanisms can regulate gene expression via chemical modifications of DNA bases and alterations to the chromosomal structure of DNA. Reproduced with permission from a website of “Zymo Research”, Available online: https://www.zymoresearch.com/pages/what-is-epigenetics (accessed on 20 April 2021).

2.1. DNA Methylation

DNA methylation is one of the best-characterized chromatin modifications. The human genome is mostly methylated on CG bases cytosine–phosphate–guanine motifs, which are enriched in promoters. The methylation of these regions by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) causes gene silencing. Abnormal DNA methylation is associated with the pathogenesis of PD. DNMTs are the enzymes for the establishment and maintenance of DNA methylation patterns. However, there is a hypothesis that DNA methylation may not be the most attractive target for the development of PD treatment [4]. Other mechanisms, such as global hyperacetylation, and histone deacetylase (HDAC) dependent regulation of α-synuclein expression may be more prominent targets from the current perspective. Corresponding histone modifiers may become convenient targets for small molecule inhibition therapeutics in the future [4].

2.2. DNA Methylation Changes in PD

Several alterations in DNA methylation associated with PD pathogenesis are described. For example, DNMT1 catalyzing DNA methylation is downregulated in the postmortem brain samples of PD patients [5]. Although disputable due to the insufficiency of direct evidence [6], those changes may be associated with alterations in the gene expression of α-synuclein and other genes implicated in PD development, ultimately causing abnormal protein aggregation [5].

An important association of DNMT1 with PD pathogenesis was described by Desplats and coauthors [7]. They reported that DNMT1 is downregulated in the postmortem brain of PD patients [7]. A global 30% reduction in DNA methylation correlates with an increased level of α-synuclein and associated sequestering of DNMT1 outside the nucleus [7]. However, the study of the role of DNMT1 in the DNA methylation of the α-synuclein gene brought contradictory and inconclusive results concerning this process’s details [8]. It was reported that the protein expression of DNMT1 was reduced, whereas the corresponding mRNA levels increased in the cellular and mouse models of PD [9]. Further investigation identified a role of an additional regulator of the methylation process. As shown recently, miR-17 mediates DNMT1 downregulation and may be responsible for the aberrant DNA methylation in PD [9].

2.3. Histone Acetylation

The imbalance of histone acetylation also plays an important role in PD pathogenesis. Several types of histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases are involved in regulating the acetylation of histone lysine residues [10]. For example, modification of the DNA packaging protein histone H3 (H3K27ac) dysregulates α-synuclein expression, one of the important players in PD.

There is an opinion that DNA hydroxymethylation, global hyperacetylation, and HDAC dependent regulation of α-synuclein expression play a more significant role in PD development than mechanisms directly controlling DNA methylation [4]. The treatment with DNMT inhibitors in vitro indicates that DNA methylation is a potent mechanism for α-synuclein downregulation. The best-studied regulator of α-synuclein expression is a CpG island in intron 1. Its efficiency is especially high in cells with a low endogenous level of α-synuclein expression [4].

2.4. Other Epigenetic Mechanisms Associated with PD

Other important epigenetic players are the noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs). Recent genome-wide studies have shown that <2% of the human genome codes for proteins. However, the genome is extensively transcribed, producing regulatory noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs). Noncoding RNAs may be categorized in two main groups on the basis of their length. The most thoroughly studied microRNAs (miRNAs) are 20–22 nucleotide-long molecules that downregulate the gene expression on the post-transcriptional level, binding to mRNAs. Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) have lengths of more than 200 nucleotides. They regulate gene expression through various mechanisms, most often at the epigenetic level [11]. LncRNAs exist in either a linear or a circular form (circRNAs). There is growing evidence that noncoding RNAs play a significant, but not yet completely understood role in the PD pathogenesis [12].

3. Role of Epigenetics in DLB

Funahashi et al. examined an association of CpG island methylation level in the α-synuclein gene with DLB [13]. The authors found that intron 1 methylation in leucocytes is significantly reduced in DLB patients compared to controls. Similar results indicating a reduction in DNA methylation in DLB patients were described by Desplats (2011) [7]. These authors found that hypomethylation is associated with the translocation of DNMT1 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, similar to the findings described in PD patients [7]. Thus, similar epigenetic dysregulation occurs in DLB and PD.

In addition to the hypomethylation of the α-synuclein gene, the epigenetic regulation of other genes associated with DLB has been proposed, including ataxin 2 (ATXN2), deglycase PARK7 and parkin (PRKN) [14]. Furthermore, changes in H3 histone acetylation might also contribute to LBD development [14]. Since epigenetic modifications in DLB patients are reversible and dynamic, they are used as appropriate targets for DLB treatment.

5.4. Epigenetic Mechanisms in MSA

Several epigenetic mechanisms are associated with MSA pathogenesis. Rydbirk and coauthors have investigated 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine changes throughout the genome of MSA patients and control individuals [15]. They found five significantly different 5mC probes in the genome of MSA patients. One of these probes mapped to the apoptosis resistant E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 (AREL1) gene implicated in antigen presentation was reduced in MSA patients. This decrease correlated with elevated 5 mC levels. Several functional DNA methylation modules are involved in inflammatory processes. In the brains of MSA patients, reduced 5 mC levels on AREL1 were concordant with elevated level of gene expression of both AREL1 and MHC Class I HLA genes.

In another study consistent alterations in myelin-associated oligodendrocyte basic protein (MAOBP) and huntingtin interacting protein 1 (HIP1) DNA methylation status were described in MSA patients [16][17]. In particular, reduced MOBP mRNA levels correlated with elevated DNA methylation in MSA patients. A distinct association between the methylation of HIP1 DNA and gene expression levels has been found in MSA patients compared to healthy controls [16]. These results propose that this locus is subjected to epigenetic remodeling in MSA.

In another study, Bettencourt and coauthors [17] described DNA methylation changes across brain regions in MSA with different degrees of GCI pathology. We identified 157 CpG sites and 79 genomic regions where DNA methylation was significantly altered in the MSA cases. Some DNA methylation changes mirror the MSA-associated pathology, for example, cerebellum-specific alterations [17].

Thus, multiple lines of evidence indicate that epigenetic mechanisms play an important role in all three main forms of synucleinopathies: PD, DLB and MSA. Accumulating data suggest that epigenetic mechanisms may be regulated by various environmental factors, including dietary phytochemicals—substances of plant origin that possess biological activity. Moreover, there is an opinion that the selection of appropriate phytochemicals with known mechanisms of action may allow using them for the treatment of these disorders.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biom11050624

References

- Griñán-Ferré, C.; Bellver-Sanchis, A.; Izquierdo, V.; Corpas, R.; Roig-Soriano, J.; Chillón, M.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Somogyvári, M.; Sőti, C.; Sanfeliu, C.; et al. The pleiotropic neuroprotective effects of resveratrol in cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease pathology: From antioxidant to epigenetic therapy. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 67, 101271.

- Tiffon, C. The Impact of Nutrition and Environmental Epigenetics on Human Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3425.

- Marshall, L.L.; Killinger, B.A.; Ensink, E.; Li, P.; Li, K.X.; Cui, W.; Lubben, N.; Weiland, M.; Wang, X.; Gordevicius, J.; et al. Epigenomic analysis of Parkinson’s disease neurons identifies Tet2 loss as neuroprotective. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 1203–1214.

- Van Heesbeen, H.J.; Smidt, M.P. Entanglement of Genetics and Epigenetics in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 277.

- Liu, L.; Van Groen, T.; Kadish, I.; Tollefsbol, T.O. DNA methylation impacts on learning and memory in aging. Neurobiol. Aging 2009, 30, 549–560.

- Bs, C.S.; Siegel, A.; Liang, W.S.; Pearson, J.V.; Stephan, D.A.; Shill, H.; Connor, D.; Caviness, J.N.; Sabbagh, M.; Beach, T.G.; et al. Neuronal gene expression correlates of Parkinson’s disease with dementia. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 1588–1595.

- Desplats, P.; Spencer, B.; Coffee, E.; Patel, P.; Michael, S.; Patrick, C.; Adame, A.; Rockenstein, E.; Masliah, E. α-Synuclein Sequesters Dnmt1 from the Nucleus. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 9031–9037.

- Guhathakurta, S.; Bok, E.; Evangelista, B.A.; Kim, Y.-S. Deregulation of α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease: Insight from epigenetic structure and transcriptional regulation of SNCA. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017, 154, 21–36.

- Zhang, H.-Q.; Wang, J.-Y.; Li, Z.-F.; Cui, L.; Huang, S.-S.; Zhu, L.-B.; Sun, Y.; Yang, R.; Fan, H.-H.; Zhang, X.; et al. DNA Methyltransferase 1 Is Dysregulated in Parkinson’s Disease via Mediation of miR. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 1–14.

- Gräff, J.; Tsai, L.-H. Histone acetylation: Molecular mnemonics on the chromatin. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 97–111.

- Network, T.C. Long noncoding RNAs in cardiac development and ageing. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 415–425.

- Acharya, S.; Salgado-Somoza, A.; Stefanizzi, F.M.; Lumley, A.I.; Zhang, L.; Glaab, E.; May, P.; Devaux, Y. Non-Coding RNAs in the Brain-Heart Axis: The Case of Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6513.

- Funahashi, Y.; Yoshino, Y.; Yamazaki, K.; Mori, Y.; Mori, T.; Ozaki, Y.; Sao, T.; Ochi, S.; Iga, J.-I.; Ueno, S.-I. DNA methylation changes at SNCAintron 1 in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 71, 28–35.

- Urbizu, A.; Beyer, K. Epigenetics in Lewy Body Diseases: Impact on Gene Expression, Utility as a Biomarker, and Possibilities for Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4718.

- Rydbirk, R.; Folke, J.; Busato, F.; Roché, E.; Chauhan, A.S.; Løkkegaard, A.; Hejl, A.-M.; Bode, M.; Blaabjerg, M.; Møller, M.; et al. Epigenetic modulation of AREL1 and increased HLA expression in brains of multiple system atrophy patients. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 1–14.

- Bettencourt, C.; Miki, Y.; Piras, I.S.; De Silva, R.; Foti, S.C.; Talboom, J.S.; Revesz, T.; Lashley, T.; Balazs, R.; Viré, E.; et al. MOBP and HIP1 in multiple system atrophy: New α-synuclein partners in glial cytoplasmic inclusions implicated in the disease pathogenesis. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2020.

- Bettencourt, C.; Foti, S.C.; Miki, Y.; Botia, J.; Chatterjee, A.; Warner, T.T.; Revesz, T.; Lashley, T.; Balazs, R.; Viré, E.; et al. White matter DNA methylation profiling reveals deregulation of HIP1, LMAN2, MOBP, and other loci in multiple system atrophy. Acta Neuropathol. 2020, 139, 135–156.