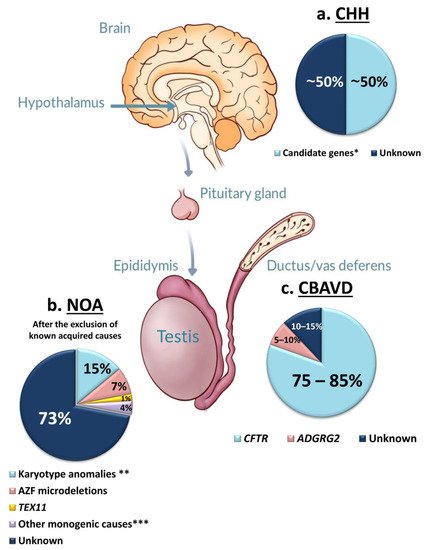

Azoospermia affects 1% of men, and it can be due to: (i) hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction, (ii) primary quantitative spermatogenic disturbances, (iii) urogenital duct obstruction. Known genetic factors contribute to all these categories, and genetic testing is part of the routine diagnostic workup of azoospermic men. The diagnostic yield of genetic tests in azoospermia is different in the different etiological categories, with the highest in Congenital Bilateral Absence of Vas Deferens (90%) and the lowest in Non-Obstructive Azoospermia (NOA) due to primary testicular failure (~30%). Whole-Exome Sequencing allowed the discovery of an increasing number of monogenic defects of NOA with a current list of 38 candidate genes. These genes are of potential clinical relevance for future gene panel-based screening.

- azoospermia

- infertility

- genetics

- Exome

- NGS

- NOA

- Klinefelter syndrome

- Y chromosome microdeletions

- CBAVD

- congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism

1. Introduction

2. Chromosomal Anomalies Causing Azoospermia

2.1. Karyotype Anomalies

2.1.1. Klinefelter Syndrome (47,XXY)

2.1.2. 46,XX Testicular/Ovo-Testicular Disorder of Sex Development

2.1.3. Yq–

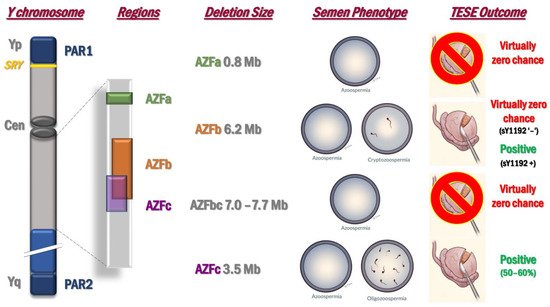

2.2. Microdeletions of the Y Chromosome: AZF Deletions

3. Monogenic Forms of Azoospermia

3.1. Congenital Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism (CHH)

3.2. Congenital Bilateral Absence of Vas Deferens (CBAVD)

3.3. Primary Testicular Failure

| (a) | |||||||||||

| Gene ^ | OMIM | Locus ° | Function + | Inheritance | Other Phenotypes | POI | Mouse Reproductive Phenotypes # | Segregation in Family | More than One Unrelated Carrier | Independent Cohorts | Refs. |

| FANCA | 607139 | 16q24.3 | Interstrand crosslink repair | AR | Fanconi Anemia | Yes | Abnormal male meiosis, decreased germ cell number, decreased mature ovarian follicle number, absent ovarian follicles | Yes | Yes | No | [82] |

| PLK4 | 605031 | 4q28.1 | Centriole duplication during the cell cycle | AD | Microcephaly and chorioretinopathy | No | Decreased male germ cell number | No | No | No | [83] |

| WNK3 | 300358 | Xp11.22 | Regulation of electrolyte homeostasis, cell signaling, survival and proliferation | XLR | n.r. | No | Normal * | Yes | No | No | [84] |

| (b) | |||||||||||

| Gene ^ | OMIM | Locus ° | Function + | Inheritance | Other Phenotypes | POI | Mouse Reproductive Phenotypes # | Segregation in Family | More than One Unrelated Carrier | Independent Cohorts | Refs. |

| ADAD2 | n.a. | 16q24.1 | dsRNA-binding protein, RNA editing | AR | n.r. | No | Male and female infertility | Yes | Yes | Yes | [10] |

| C14orf39 | 617307 | 14q23.1 | Chromosome synapsis during meiotic recombination | AR | n.r | Yes | Arrest of male meiosis, abnormal chiasmata formation, abnormal chromosomal synapsis, abnormal X-Y chromosome synapsis during male meiosis, absent oocytes | Yes ** | Yes | No | [85] |

| DMC1 | 602721 | 22q13.1 | Meiotic recombination, DNA DSB repair | AR | n.r. | Yes | Arrest of male meiosis decreased oocyte number, absent oocytes, absent ovarian follicles, abnormal female meiosis | Yes ** | No | No | [86] |

| KASH5 | 618125 | 19q13.33 | Meiotic telomere attachment to nuclear envelope in the prophase of meiosis, homolog pairing during meiotic prophase | AR | n.r. | No | Arrest of male meiosis, female infertility | Yes | No | No | [84] |

| MAJIN | 617130 | 11q13.1 | Meiotic telomere attachment to the nucleus inner membrane during homologous pairing and synapsis | AR | n.r. | No | Meiotic arrest, male and female infertility | No | No | No | [87] |

| MEI1 | 608797 | 22q13.2 | Meiotic chromosome synapsis, DBS formation | AR | Hydatidiform mole | Yes | Arrest of male meiosis, female infertility | Yes | Yes | Yes | [10,88,89] |

| MEIOB | 617670 | 16p13.3 | DNA DSB repair, crossover formation and promotion to complete synapsis | AR | n.r. | Yes | Arrest of spermatogenesis, decreased oocyte number, absent oocytes | Yes | Yes | Yes | [10,90,91] |

| MSH4 | 602105 | 1p31.1 | Homologous chromosomes recombination and segregation at meiosis I | AR | n.r. | Yes | Azoospermia, abnormal male and female meiosis | No | Yes | Yes | [10] |

| RAD21L1 | n.a. | 20p13 | Meiosis-specific component of some cohesin complex | AR | n.r. | No | Arrest of male meiosis, absent oocytes, decreased mature ovarian follicle number, absent primordial ovarian follicles | Yes | No | No | [10] |

| RNF212 | 612041 | 4p16.3 | Regulator of crossing-over during meiosis | AR | n.r. | No | Arrest of male meiosis, female infertility | Yes | No | No | [92] |

| SETX | 608465 | 9q34.13 | DNA and RNA processing | AR | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2 | Yes | Arrest of male meiosis, globozoospermia, reduced female fertility | No | Yes | Yes | [93,94] |

| SHOC1 | 618038 | 9q31.3 | Binds to single-stranded DNA and DNA branched structures; formation of crossover recombination intermediates | AR | n.r. | No | Arrest of male meiosis | Yes | Yes | Yes | [10,95] |

| SPINK2 | 605753 | 4q12 | Inhibitor of acrosin | AR | n.r. | No | Kinked sperm flagellum, oligozoospermia, teratozoospermia, abnormal male germ cell apoptosis | Yes | No | No | [1,96] |

| SPO11 | 605114 | 20q13.31 | Initiation of DSBs | AR | n.r. | No | Arrest of male meiosis, decreased oocyte number, oocyte degeneration, abnormal female meiosis | Yes | No | No | [84] |

| STAG3 | 608489 | 7q22.1 | Cohesion of sister chromatids, DNA DSB repair | AR | n.r. | Yes | Azoospermia, absent oocytes | Yes ** | Yes | Yes | [10,92,97,98] |

| STX2 | 132350 | 12q24.33 | Sulfoglycolipid transporter | AR | n.r. | No | Arrest of male meiosis | No | No | No | [99] |

| SYCE1 | 611486 | 10q26.3 | Chromosome synapsis in meiosis | AR | n.r. | Yes | Arrest of male meiosis, decreased mature ovarian follicle number | Yes | Yes | Yes | [10,100,101] |

| TDRD7 | 611258 | 9q22.33 | RNA processing | AR | Congenital cataract | No | Arrest of spermatogenesis, abnormal male germ cell apoptosis | Yes | Yes | No | [2,102] |

| TERB1 | 617332 | 16q22.1 | Meiotic telomere attachment to the nucleus inner membrane during homologous pairing and synapsis | AR | n.r. | No | Arrest of male meiosis, absent oocytes, absent ovarian follicles, abnormal female meiosis I arrest | Yes | Yes | Yes | [10,87] |

| TERB2 | 617131 | 15q21.1 | Meiotic telomere attachment to the nucleus inner membrane during homologous pairing and synapsis | AR | n.r. | No | Arrest of male meiosis, absent ovarian follicles, abnormal female meiosis | Yes | No | No | [87] |

| TEX11 | 300311 | Xq13.1 | Chromosome synapsis and formation of crossovers | XLR | n.r. | No | Arrest of male meiosis, meiotic non-disjunction during M1 phase | Yes | Yes | Yes | [10,103,104,105] |

| XRCC2 | 600375 | 7q36.1 | Interstrand crosslink repair, DNA DSB repair | AR | Fanconi Anemia | Yes | Meiotic arrest, POI | Yes ** | No | No | [106] |

| ZMYND15 | 614312 | 17p13.2 | Transcriptional repressor | AR | n.r. | No | Azoospermia | Yes | No | No | [107] |

| (c) | |||||||||||

| Gene ^ | OMIM | Locus ° | Function + | Inheritance | Other Phenotypes | POI | Mouse Reproductive Phenotypes # | Segregation in Family | More than One Unrelated Carrier | Independent Cohorts | Refs. |

| DMRT1 | 602424 | 9p24.3 | Transcription factor involved in male sex determination and differentiation | AD | Ambiguous genitalia and sex reversal | No | Abnormal male meiosis, male infertility | Yes | Yes | Yes | [10,108] |

| FANCM | 609644 | 14q21.2 | DNA DSB repair, interstrand cross-link removal | AR | n.r. | Yes | Azoospermia, decreased mature ovarian follicle number | Yes | Yes | Yes | [109,110] |

| M1AP | 619098 | 2p13.1 | Meiosis I progression | AR | n.r. | No | From arrest of male meiosis to severe oligozoospermia/globozoospermia | Yes | Yes | Yes | [111] |

| NANOS2 | 608228 | 19q13.32 | Spermatogonial stem cell maintenance | AR | n.r. | No | Azoospermia, abnormal female meiosis | Yes | Yes | No | [84] |

| NR5A1 | 184757 | 9q33.3 | transcriptional activator for sex determination | AD | 46, XY and 46, XX sex reversal; adrenocortical insufficiency | Yes | From oligozoospermia to arrest of spermatogenesis, decreased mature ovarian follicle number, absent mature ovarian follicles | Yes ** | Yes | Yes | [112,113,114,115,116] |

| TAF4B | 601689 | 18q11.2 | Transcriptional coactivator | AR | n.r. | No | Oligozoospermia, decreased male germ cell number, asthenozoospermia, absent mature ovarian follicles, impaired ovarian folliculogenesis | Yes | No | No | [107] |

| TDRD9 | 617963 | 14q32.33 | Repression of transposable elements during meiosis | AR | n.r. | No | Arrest of male meiosis | Yes | No | No | [117] |

| TEX14 | 605792 | 17q22 | Formation of meiotic intercellular bridges | AR | n.r. | No | Arrest of male meiosis | Yes | Yes | Yes | [10,84,90] |

| TEX15 | 605795 | 8p12 | Chromosome, synapsis, DNA DSB repair | AR | n.r. | No | Arrest of male meiosis | Yes | Yes | Yes | [118,119] |

| WT1 | 607102 | 11p13 | Transcription factor | AD | Wilms tumor type 1; Nephrotic sdr type 4; Denys-Drash sdr; Frasier sdr; Meacham sdr; Mesothelioma | Yes | Azoospermia | No | Yes | Yes | [120,121,122] |

| (d) | |||||||||||

| Gene ^ | OMIM | Locus ° | Function + | Inheritance | Other Phenotypes | POI | Mouse Reproductive Phenotypes # | Segregation in Family | More than One Unrelated Carrier | Independent Cohorts | Refs. |

| MCM8 | 608187 | 20p12.3 | DNA DSB repair, interstrand crosslink removal | AR | n.r. | Yes | Arrest of male meiosis, decreased oocyte number, decreased mature ovarian follicle number, increased ovary tumor incidence, increased ovary adenoma incidence | Yes ** | No | No | [123] |

| PSMC3IP | 608665 | 17q21.2 | Stimulating DMC1-mediated strand exchange required for pairing homologous chromosomes during meiosis. | AR | Ovarian dysgenesis | Yes | Arrest of male meiosis, absent ovarian follicles, abnormal ovary development | Yes ** | No | No | [124] |

3.3.1. Candidate Genes for the SCOS Phenotype

3.3.2. Candidate Genes for the MA Phenotype

3.3.3. Candidate Genes Associated with Different Types of Testicular Phenotype

3.3.4. Candidate Genes for iNOA with Undefined Testicular Phenotype

4. Common Monogenic Defects in Male and Female Primary Gonadal Failure

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22063264