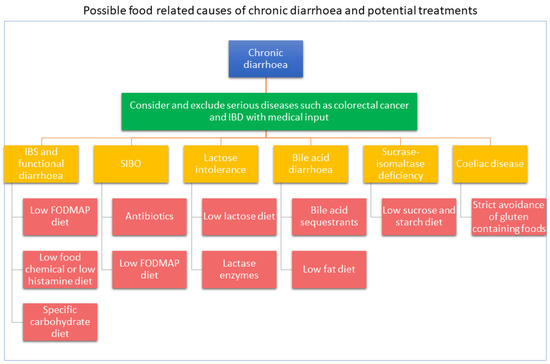

Chronic diarrhoea affects up to 14% of adults, it impacts on quality of life and its cause can be variable. Patients with chronic diarrhoea are presented with a plethora of dietary recommendations, often sought from the internet or provided by those who are untrained or inexperienced. Once a diagnosis is made, or serious diagnoses are excluded, dietitians play a key role in the management of chronic diarrhoea. The dietitian’s role varies depending on the underlying cause of the diarrhoea, with a wide range of dietary therapies available. Dietitians also have an important role in educating patients about the perils and pitfalls of dietary therapy.

- chronic diarrhoea

- diet

- irritable bowel syndrome

- FODMAP

- SIBO

- lactose intolerance

- bile acid diarrhoea

- sucrase-isomaltase deficiency

- dietitian

Note: The following contents are extract from your paper. The entry will be online only after author check and submit it.

1. Introduction

1.1. Diet Seeking Behaviour by Patients with Gastrointestinal Symptoms

1.2. Understanding the Role of Diet in the Management of Chronic Diarrhoea

2. Dietary Management of Chronic Diarrhoea

2.1. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and Functional Diarrhoea

2.1.1. Dietary Therapies for IBS

| Disease | Dietary Therapy | Pearls | Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) | Low FODMAP diet | The most studied dietary intervention across all age groups. | The long length of time to establish likely trigger foods. |

| There are multiple resources; designated websites, apps, recipes, Facebook pages, books, magazines. | Obsolete and outdated information is likely; resources need regular review by qualified health professionals. | ||

| Comprehensive dietitian training is available. | FODMAP content differs by country. Individual tolerance may differ. | ||

| Commercial product FODMAP testing is available increases consumer choice. | Phase 1 may restrict prebiotic food intake. | ||

| A modified version can be used with those at high risk. | Restrictive diets may contribute to disordered eating patterns. | ||

| Small amounts of wheat are allowed so a gluten-free diet is not required. | Phase 1 may reduce abundance of multiple bacterial species. | ||

| High-lactose dairy is avoided. A dairy free diet is not required. | |||

| Specific-carbohydrate diet | Breaking the Vicious Cycle book provides detailed instruction. | Limited evidence of mechanisms, food composition and efficacy. | |

| Online support is available. | Long length of time to achieve improvements. | ||

| No evidence of impact on diet adequacy, quality of life and mental health. | |||

| Limited and conflicting guidance on use of the diet and reintroducing foods. | |||

| Restrictive diets may contribute to disordered eating patterns. | |||

| Likely restricts prebiotic food intake and nutrient intake. | |||

| The low-food chemical/low-histamine diet | The Royal Prince Alfred Hospital provides detailed instruction for the low-food chemical diet. | Limited evidence of efficacy. | |

| There are multiple resources; designated websites, apps, recipes, Facebook pages, books. | Limited and conflicting food chemical content data. | ||

| Relatively short elimination period. | Triggers may be non-diet related. | ||

| A modified version can be used with those at high risk. | Likely restricts prebiotic and nutrient intake. | ||

| May address a wider range of intolerances. | Restrictive diets may contribute to disordered eating patterns. | ||

| Small intestinal bacteria overgrowth (SIBO) | Low FODMAP diet | Excellent support information available. | Online information is prevalence, but given the lack of evidence in this field, it is likely to lack any validity. |

| Dietary changes may not be needed if antibiotics are effective | Reoccurrence of SIBO is common, risking nutritional deficiencies if repeated dietary restriction is conducted. | ||

| Elemental diet | Nutritional complete | Provides no fibre and restricts prebiotics. | |

| Patients may not require any dietary restrictions. | May not be palatable and therefore poorly tolerated. | ||

| Lactose intolerance | Low-lactose diet | Credible methods for diagnosing are available. | Lactose-free products or lactase enzymes may not be easily available or affordable for all. |

| Suitable alternatives are available providing nutrition in similar amounts. | Risk of low intake of calcium and vitamin D. | ||

| High-lactose dairy is avoided. A dairy free diet is not required. | |||

| Bile acid diarrhoea | Low-fFat diet | May be better tolerated than bile acid sequestrants. | Risk of inadequate intake of fat-soluble vitamins and reduction in overall energy intake leading to unintended weight loss. |

| Dietary changes may not be needed if bile acid sequestrants are effective | A variety of low-fat products are readily available at same cost to the full fat varieties. | ||

| Sucrase-isomaltase deficiency (SID) | Low-sucrose/starch diet | There are multiple resources; designated websites, apps, recipes, Facebook pages, books. | Limited research on the long-term management of dietary changes. |

| Oral enzymes are available to allowing for a broader range of foods to be eaten. | Sucrose enzymes are not available in all countries. | ||

| With good planning the diet can still provide adequate fibre. | May restrict prebiotic food intake. | ||

| Limited research on the long-term management of dietary changes. | |||

| Coeliac disease | Gluten-free diet | Gold standards for diagnosis. | Lifelong avoidance of all gluten-containing food is required. |

| Gluten-free food alternatives are readily available. | Cross contamination can occur. | ||

| There are multiple resources; designated websites, apps, recipes, Facebook pages, books. | Gluten-free alternatives can be more expensive, reducing diet compliance for some. |

| Potential Pitfall | Management Strategy |

|---|---|

| Unnecessary use of restrictive diet | Rule out other potential causes such as IBD, coeliac disease, diverticular disease, colorectal cancer [17] |

| Consider general lifestyle and dietary advice first such as the NICE guidelines [17] | |

| Diagnostic testing to rule out SIBO and lactose malabsorption if available | |

| Nutritional deficiencies | Review oral intake prior to commencing diet to determine if any already existing nutrient deficiencies |

| Discuss suitable food alternatives | |

| Consider nutritional supplements for likely nutrient deficits | |

| Diet restrictiveness | Consider lifestyle and general dietary advice first, e.g., NICE guidelines [17] |

| Consider a modified version of the diet [44,45] | |

| Discuss food swaps where examples of food alternatives are given for each suggested eliminated food | |

| Develop a personalised plan during dietary eliminations [78] | |

| Provide shopping lists of suitable alternatives | |

| Provide recipe ideas and discuss meal planning | |

| Reintroduce restricted foods in a timely manner if improvements with symptoms or advise return to usual diet if not improvement was experienced | |

| Develop a personalised plan to include previously restricted foods that have been tolerated during the reintroduction phase | |

| Encourage frequent reintroduction of identified trigger foods, if appropriate, to test if threshold tolerance has increased | |

| Changes in the microbiome | Promote diet diversity to prevent reducing fermentable fibre [79], encourage allowed foods that may not have been eaten before starting the diet |

| Encourage vegetables or fruit at all meal times, pectin-containing fruit and vegetables may be better tolerated prebiotics [79] | |

| Encourage a fibre supplement if fibre intake is likely to be low [22] |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu13051393