Drug-specific therapeutic approaches for colorectal cancer (CRC) have contributed to a significant improvement in the health status of patients. However, a great need to improve personalization of treatments based on genetic and epigenetic tumor profiles to maximize quality and efficacy while limiting cytotoxicity remains. Currently, CEA and CA 19-9 are the only validated blood biomarkers in clinical practice. For this reason, laboratories are trying to identify new specific prognostic and, more importantly, predictive biomarkers for CRC patient profiles. Thus, the unique landscape of personalized biomarker data should have a clinical impact on CRC treatment strategies and molecular genetic screening tests should become the standard method for CRC diagnosis, as well as detection of disease progression.

- biomarkers

- colorectal cancer

- early detection examination

- liquid biopsy

- personalized medicine

- tumor treatment

- exosomes

- ctDNA

- CTC

1. Introduction

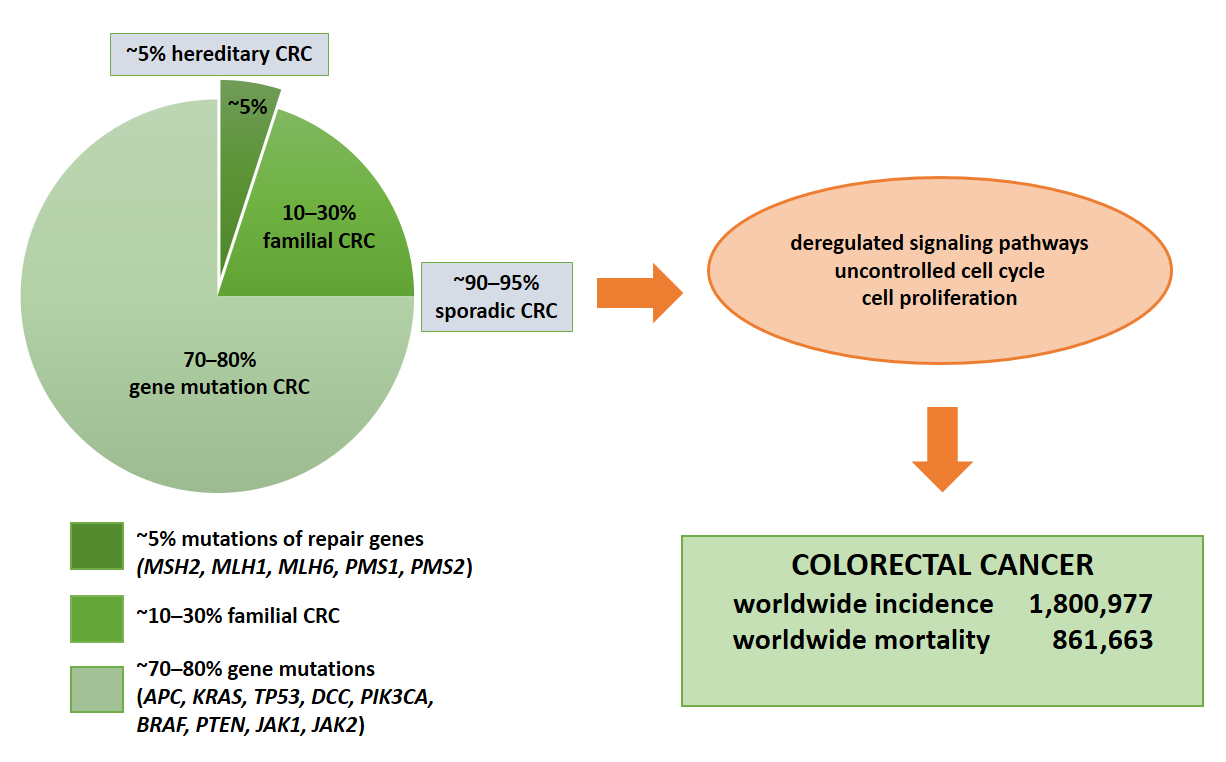

Colorectal cancer (CRC) represents the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1], with an annual incidence of nearly two million cases [2] (Figure 1). Moreover, the CRC incidence is increasing in low- and middle-income countries [1]. The disease results from the accumulation of multiple genetic and epigenetic modifications that lead to the transformation of colonic epithelial cells into invasive and aggressive adenocarcinomas [3][4]. The lack of and inadequate response to numerous mono-target therapies in cancer treatment emphasizes the need for personalized diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for effective strategies that target not only tumor cells, but more importantly the multicellular tumor microenvironment to improve patient outcomes. Nevertheless, one of the most important keys to the successful treatment of this malignant tumor and patient survival is not only the early diagnosis of the disease but also the control of tumor dissemination and progression [5]. Thus, the 5-year survival rate for patients with early diagnosis is approximately 90%. In contrast, the survival rate for patients with regional lymph node metastasis is about 70%, and for those with distant metastases is only 13% [6][7].

Figure 1. Molecular basis of CRC. Colorectal cancer is based on gene mutations, familial or hereditary CRC. The indication of total numbers refers to Global Cancer Statistics 2018 [3]. For worldwide incidence and mortality, colorectal cancer cases from 185 countries in 2018 were summed.

Other important keys to improving CRC therapies include improvements in surgical modalities and adjuvant chemotherapy, which has increased cure rates for early-stage disease. However, a significant proportion of patients will unfortunately develop recurrence or advanced disease. Nevertheless, the efficacy of chemotherapy for recurrence and advanced stages of CRC has improved significantly over the past decade. Previously, the historical drug 5-fluorouracil was the only chemotherapeutic agent used. With the addition of other chemotherapeutic agents such as capecitabine, irinotecan, oxaliplatin, bevacizumab, cetuximab, panitumumab, vemurafenib, and dabrafenib, the median survival of patients with oligometastatic CRC has improved significantly from less than one year to the current standard of nearly two years [8]. However, many side effects of systemic therapy, such as toxicity, can lead to fatal complications and significantly affect patients’ quality of life. In parallel, a plethora of biologically active compounds are being tested in vitro and in vivo, and promising hits/leads compounds are being identified for development as adjuncts to therapy [9][10]. Thus, there is an urgent need for crucial biomarkers to select optimal drugs individually or in combination for an individual patient. The application of personalized therapy based on DNA testing could help clinicians provide the most effective chemotherapeutic agents and dose modifications for each patient. However, some of the current findings are controversial, and the evidence is conflicting [11]. The current trend is to achieve successful personalized therapeutic approaches based on monitoring disease-specific biomarker(s). Finally, data in this respect are scarce, and studies involving personalized testing versus treatment are needed.

2. Etiology of Colorectal Cancer

The CRC-related genes and pathways often overlap with other solid tumors, such as breast and prostate cancer. In approximately 70–90% of patients, CRC develops sporadically due to point mutations in the APC, KRAS, TP53, and DCC genes.

In approximately 1–5% of cases, it is a consequence of hereditary polypoid and non-polypoid syndrome and 10–30% of patients have a familial CRC [12] (Figure 1). It is important to note that 1–2% of CRC are associated with chronic inflammatory diseases such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. The risk increases with longer duration of ongoing inflammation [13], which is also caused by dysbiosis in the gut [14] and inappropriate dietary patterns and deteriorating life-style conditions [15]. Chromosomal instability (CIN) as a major molecular pathway of malignant transformation mainly affects genes such as APC, KRAS, PIK3CA and TP53 [16]. In addition, the adenoma–carcinoma sequence offers potential for screening and surveillance; for example, expression of connexin 43 in colonic adenomas is associated with high-grade dysplasia and colonic mucosa surrounding adenomas [17]. APC mutations lead to nuclear beta-catenin translocations and transcription of genes involved in carcinogenesis and invasion processes. KRAS and PIK3CA mutations lead to continuous activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, which in turn increases cell proliferation, while TP53 mutations lead to loss of p53 function and uncontrolled cell cycle [16]. Finally, epigenetic instability (CIMP) is associated with hypermethylation of the promoter of oncogenes and loss of expression of the corresponding proteins [18].3. The impact of Genetic Alterations on Disease Outcome

The most common mutations, chromosomal alterations and translocations affect critical wingless-related integration sites (WNT), MAPK/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling pathways and intracellular protein functions such as p53, as well as cell cycle regulation [19]. The WNT signaling pathway, which is a critical mediator of tissue homeostasis and repair, is frequently co-opted during tumor development. Almost all colorectal cancers demonstrate hyperactivation of the WNT pathway, which is considered to be the initiating and driving event in many cases [20]. APC gene mutations represent the most significant genetic alteration associated with the WNT signaling pathway, which regulates stem cell differentiation and cell growth. Nevertheless, due to their high CRC frequency and the number of different mutations identified within the gene, they are not a good predictor of disease progression [21]. Increased β-catenin expression associated with the WNT signaling pathway has also been found to be an unreliable marker for disease prognosis. In contrast, overexpression of the c-MYC gene triggered by activation of the WNT signaling pathway represents a good predictor of metastasis and disease progression [22][23]. KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA mutations are common and associated with the MAPK/PI3K signaling pathways.

Furthermore, mutations of the KRAS gene in exon 2, codon 13 are associated with poor prognosis and a low survival rate, while mutations in exon 2 and codon 12 are associated with tumor progression and metastasis [24][25]. Recently, AMG 510, the first KRAS G12C inhibitor, has entered into the clinical development after promising preclinical results [26]. These are intriguing efforts that could overcome the notion that KRAS is in principle "undruggable" as a therapeutic target and may contribute to the development of effective drugs for targeting traditionally difficult signaling pathways in the clinical setting [27]. BRAF gene mutations are associated with poor prognosis and survival [28][29][30].

The associations between disease outcome or survival and PIK3CA mutations have not yet been established. Nevertheless, there is evidence that these mutations, in combination with the KRAS gene mutations, are associated with poor outcome [31]. Moreover, CRC patients with multiple PIK3CA mutations, e.g., a combination of mutations in exons 9 and 20, have a worse prognosis than patients with only one of these mutations [32]. Protein phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) adversely affects the PI3K signaling pathway and CRC in which loss of the PTEN gene has been associated with poor prognosis [33]. In CRC patients, alterations in the TGF-β signaling pathway are associated with CIN [34]. Chromosome 18q carries the tumor suppressor genes SMAD2 and SMAD4, whose encoded proteins are functionally associated with apoptosis and cell cycle regulation [35][36]. Similarly, they play a role in tumor cell migration by regulating the activity of proteins such as matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9) [37]. A significant association between the loss of chromosome 18q and poor prognosis and survival has not been found [35][36]. In CRC, loss of the 17q-TP53 gene, which encodes the tumor suppressor protein p53 that regulates the cell cycle, is quite common. Without it, cells proliferate uncontrollably and the tumor progresses [38]. Janus kinases, JAK1 and JAK2, are associated with cytokine receptors [39][40], and cytokine binding leads to their activation and phosphorylation. Subsequently, Janus kinases phosphorylate signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins, leading to their translocation to the nucleus and transcription of their target genes [39][40]. There is evidence of JAK1 and JAK2 gene mutations that inhibit the function of the corresponding JAK1 and JAK2 proteins. The JAK1 frameshift mutations (positions 142/143, 430/431, and 860/861) have been described as the consequence of insertion/deletion of a nucleotide [40]. The V617E mutation results in a JAK2 loss-of-function mutation [39]. These mutations were found in tumors with high MSI resulting from dysfunctional DNA repair during replication, known as mismatched repair [41]. Indeed, they were associated with tumor resistance to treatment targeting programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) [41]. The determination of molecular alterations at the DNA level, particularly derived from tumor-specific liquid components such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), exosomes, and circulating tumor cells (CTC), can improve the prediction of disease progression and help in adjustment of therapy for each patient in the context of personalized medicine.

4. Liquid Biopsy

Much has been learned about the molecular background of the development and progression of CRC, which can help to tailor therapy for each individual patient and improve their survival prognosis. However, early CRC still relies on biomarkers from readily available biological materials (Table 1). Currently, there are only two validated protein-based blood biomarkers used in routine clinical practice: carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9). CEA is an embryo-specific glycoprotein that can also be found in CRC. In clinical practice, it is used to monitor tumor progression after diagnosis [42]. However, it shows insufficient sensitivity and specificity because it is hereditarily determined and in the case of recessive homozygote, the levels of CA 19-9 would not be elevated (in approximately 15% of individuals) [43][44][45]. During the search for new biomarkers that could replace the old ones, a promising non-invasive and repeatable procedure called “liquid biopsy” has been developed for different body fluids (blood, saliva and urine). Liquid biopsy from peripheral blood is used for diagnostic screening as well as for determining response to therapy and evaluating the outcome of the disease [46]. Peripheral blood may contain CTC, ctDNA, and exosomes (vesicular structures containing proteins and RNA molecules that can be released into circulation by various cells, including tumor cells) [47]. This could allow the molecular profile of the disease, the degree of affected tissue, and the response to therapy to be determined in a non-invasive manner. The founder and establisher of new principles and methods of healing, Leroy Hood, has relentlessly emphasized that in the new era of personalized approaches undertaken while assessing different conditions and diseases, “the blood becomes a window through which we observe what is happening in the body” [48]. The same idea has been accepted and maintained by other biomedical disciplines, from genetics to personalized nutrition [49]. Future molecular profiling, ideally assessed and monitored by liquid biopsy, could further personalize decision-making in the adjuvant setting of CRC [50][51].

However, the liquid biopsy results have to be combined and evaluated with the pathological findings of the tissue before final validation of the proposed approach. The existing testing landscape presents additional challenges in the application of liquid biopsy in clinical practice, and consideration needs to be given to how the pathologist should be involved in the interpretation of liquid biopsy data in the context of the patient’s cancer diagnosis and stage assessment [52].

| Biomarker (Denotation) | Structure | Experience/Implication | Reference |

| CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen) | glycoprotein | Validated blood biomarker in clinical practice. Not recommended as a sole CRC screening test. Preoperative CEA > 5 mg/mL may correlate with poorer CRC prognosis. Used as a postoperative serum test and for monitoring every 3 months during active CRC treatment. Diagnostic sensitivity 54.5%; specificity 98.4%. | Locker et al.,2006 [42] Wu et al., 2020 [53] |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22094327

References

- Stephen R Knight; Catherine A Shaw; Riinu Pius; Thomas M Drake; Lisa Norman; Adesoji O Ademuyiwa; Adewale O Adisa; Maria Lorena Aguilera; Sara W Al-Saqqa; Ibrahim Al-Slaibi; et al. Global variation in postoperative mortality and complications after cancer surgery: a multicentre, prospective cohort study in 82 countries. The Lancet 2021, 397, 387-397, 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00001-5.

- Peng Xu; Yanliang Zhu; Bo Sun; Zhongdang Xiao; Colorectal cancer characterization and therapeutic target prediction based on microRNA expression profile. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 20616, 10.1038/srep20616.

- Freddie Bray; Jacques Ferlay Me; Isabelle Soerjomataram; Rebecca L. Siegel; Lindsey A. Torre; Ahmedin Jemal; Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2018, 68, 394-424, 10.3322/caac.21492.

- Swarnendu Tripathi; Louiza Belkacemi; Margaret S. Cheung; Rathindra N. Bose; Correlation between Gene Variants, Signaling Pathways, and Efficacy of Chemotherapy Drugs against Colon Cancers. Cancer Informatics 2016, 15, 1-13, 10.4137/CIN.S34506.

- Aitor Rodriguez-Casanova; Nicolás Costa-Fraga; Aida Bao-Caamano; Rafael López-López; Laura Muinelo-Romay; Angel Diaz-Lagares; Epigenetic Landscape of Liquid Biopsy in Colorectal Cancer. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9, 622459, 10.3389/fcell.2021.622459.

- Yuji Miyamoto; Yukiharu Hiyoshi Md; Ryuma Tokunaga Md; Takahiko Akiyama; Nobuya Daitoku; Yuki Sakamoto; Naoya Yoshida; Hideo Baba; Postoperative complications are associated with poor survival outcome after curative resection for colorectal cancer: A propensity‐score analysis. Journal of Surgical Oncology 2020, 122, 344-349, 10.1002/jso.25961.

- N Howlader; AM Noone; M Krapcho; D Miller; K Bishop; SF Altekruse; CL Kosary; M Yu; J Ruhl; Z Tatalovich; et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA; pp. 1975–2013, Based on November 2015 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2016.

- Masaki Nakamura; Shun-Ichiro Kageyama; Masahide Seki; Ayako Suzuki; Masayuki Okumura; Hidehiro Hojo; Atsushi Motegi; Tetsuo Akimoto; Liquid Biopsy Cell-free DNA Biomarkers in Patients With Oligometastatic Colorectal Cancer Treated by Ablative Radiotherapy. Anticancer Research 2021, 41, 829-834, 10.21873/anticanres.14835.

- Iveta Najmanová; Marie Vopršalová; Luciano Saso; Přemysl Mladěnka; The pharmacokinetics of flavanones. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2019, 60, 1-17, 10.1080/10408398.2019.1679085.

- Constanze Buhrmann; Parviz Shayan; Aranka Brockmueller; Mehdi Shakibaei; Resveratrol Suppresses Cross-Talk between Colorectal Cancer Cells and Stromal Cells in Multicellular Tumor Microenvironment: A Bridge between In Vitro and In Vivo Tumor Microenvironment Study. Molecules 2020, 25, 4292, 10.3390/molecules25184292.

- Nurul-Syakima Ab Mutalib; Najwa F. Md Yusof; Shafina-Nadiawati Abdul; Rahman Jamal; Pharmacogenomics DNA Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer: Current Update. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2017, 8, 736, 10.3389/fphar.2017.00736.

- Inés Mármol; Cristina Sánchez-De-Diego; Alberto Pradilla Dieste; Elena Cerrada; María Jesús Rodriguez Yoldi; Colorectal Carcinoma: A General Overview and Future Perspectives in Colorectal Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18, 197, 10.3390/ijms18010197.

- Monjur Ahmed; Colon Cancer: A Clinician’s Perspective in 2019. Gastroenterology Research 2020, 13, 1-10, 10.14740/gr1239.

- Mario Matijašić; Tomislav Meštrović; Mihaela Perić; Hana Čipčić Paljetak; Marina Panek; Darija Vranešić Bender; Dina Ljubas Kelečić; Željko Krznarić; Donatella Verbanac; Modulating Composition and Metabolic Activity of the Gut Microbiota in IBD Patients. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2016, 17, 578, 10.3390/ijms17040578.

- Donatella Verbanac; Željan Maleš; Karmela Barišić; Nutrition – facts and myths. Acta Pharmaceutica 2019, 69, 497-510, 10.2478/acph-2019-0051.

- Maria S. Pino; Daniel C. Chung; The Chromosomal Instability Pathway in Colon Cancer. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 2059-2072, 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.065.

- Alen Bišćanin; Neven Ljubičić; Marko Boban; Drinko Baličević; Ivana Pavić; Mirela Maver Bišćanin; Ivan Budimir; Zdravko Dorosulic; Marko Duvnjak; CX43 Expression in Colonic Adenomas and Surrounding Mucosa Is a Marker of Malignant Potential. Anticancer Research 2016, 36, 5437-5442, 10.21873/anticanres.11122.

- Victoria Valinluck Lao; William M. Grady; Epigenetics and colorectal cancer. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2011, 8, 686-700, 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.173.

- Daniel O. Herzig; Vassiliki L. Tsikitis; Molecular markers for colon diagnosis, prognosis and targeted therapy. Journal of Surgical Oncology 2014, 111, 96-102, 10.1002/jso.23806.

- Emma M. Schatoff; Benjamin I. Leach; Lukas E. Dow; WNT Signaling and Colorectal Cancer. Current Colorectal Cancer Reports 2017, 13, 101-110, 10.1007/s11888-017-0354-9.

- Mariana Brocardo; Beric R. Henderson; APC shuttling to the membrane, nucleus and beyond. Trends in Cell Biology 2008, 18, 587-596, 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.09.002 DOI:dx.doi.org.

- Gregory Yochum Sherri Rennoll; Regulation of MYC gene expression by aberrant Wnt/β-catenin signaling in colorectal cancer. World Journal of Biological Chemistry 2015, 6, 290-300, 10.4331/wjbc.v6.i4.290.

- Christopher W. Toon; Angela Chou; Adele Clarkson; Keshani DeSilva; Michelle Houang; Joseph C. Y. Chan; Loretta L. Sioson; Lucy Jankova; Anthony J. Gill; Immunohistochemistry for Myc Predicts Survival in Colorectal Cancer. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e87456, 10.1371/journal.pone.0087456.

- Jing Chen; Fang Guo; Xin Shi; Lihua Zhang; Aifeng Zhang; Hui Jin; Youji He; BRAF V600E mutation and KRAS codon 13 mutations predict poor survival in Chinese colorectal cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 802, 10.1186/1471-2407-14-802.

- Wenbin Li; Tian Qiu; Wenxue Zhi; Susheng Shi; Shuangmei Zou; Yun Ling; Ling Shan; Jianming Ying; Ning Lu; Colorectal carcinomas with KRAS codon 12 mutation are associated with more advanced tumor stages. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 1-9, 10.1186/s12885-015-1345-3.

- Jude Canon; Karen Rex; Anne Y. Saiki; Christopher Mohr; Keegan Cooke; Dhanashri Bagal; Kevin Gaida; Tyler Holt; Charles G. Knutson; Neelima Koppada; et al. The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2019, 575, 217-223, 10.1038/s41586-019-1694-1.

- Manuela Porru; Luca Pompili; Carla Caruso; Annamaria Biroccio; Carlo Leonetti; Targeting KRAS in metastatic colorectal cancer: current strategies and emerging opportunities. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2018, 37, 1-10, 10.1186/s13046-018-0719-1.

- Shuji Ogino; Katsuhiko Nosho; Gregory J. Kirkner; Takako Kawasaki; Jeffrey A. Meyerhardt; Massimo Loda; Edward L. Giovannucci; Charles S. Fuchs; CpG island methylator phenotype, microsatellite instability, BRAF mutation and clinical outcome in colon cancer. Gut 2008, 58, 90-96, 10.1136/gut.2008.155473.

- J Goldstein; B Tran; J Ensor; P Gibbs; HL Wong; SF Wong; E Vilar; J Tie; R Broaddus; S Kopetz; et al. Multicenter retrospective analysis of metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) with high-level microsatellite instability (MSI-H). Annals of Oncology 2014, 25, 1032-1038, 10.1093/annonc/mdu100.

- Shigenori Kadowaki; Miho Kakuta; Shuhei Takahashi; Akemi Takahashi; Yoshiko Arai; Yoji Nishimura; Toshimasa Yatsuoka; Akira Ooki; Kensei Yamaguchi; Keitaro Matsuo; et al. Prognostic value ofKRASandBRAFmutations in curatively resected colorectal cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2015, 21, 1275-83, 10.3748/wjg.v21.i4.1275.

- Rona Yaeger; Andrea Cercek; Eileen M. O'reilly; Diane L. Reidy; Nancy Kemeny; Tamar Wolinsky; Marinela Capanu; Marc J. Gollub; Neal Rosen; Michael F. Berger; et al. Pilot Trial of Combined BRAF and EGFR Inhibition in BRAF-Mutant Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients. Clinical Cancer Research 2015, 21, 1313-1320, 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-14-2779.

- Xiaoyun Liao; Teppei Morikawa; Paul Lochhead; Yu Imamura; Aya Kuchiba; Mai Yamauchi; Katsuhiko Nosho; Zhi Rong Qian; Reiko Nishihara; Jeffrey A. Meyerhardt; et al. Prognostic Role of PIK3CA Mutation in Colorectal Cancer: Cohort Study and Literature Review. Clinical Cancer Research 2012, 18, 2257-2268, 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-11-2410.

- Chloe E. Atreya; Zaina Sangale; Nafei Xu; Mary R. Matli; Eliso Tikishvili; William Welbourn; Steven Stone; Kevan M. Shokat; Robert S. Warren; PTEN expression is consistent in colorectal cancer primaries and metastases and associates with patient survival. Cancer Medicine 2013, 2, 496-506, 10.1002/cam4.97.

- Leopoldo Sarli; Lorena Bottarelli; Giovanni Bader; Domenico Iusco; Silvia Pizzi; Renato Costi; Tiziana D'adda; Marco Bertolani; Luigi Roncoroni; Cesare Bordi; et al. Association Between Recurrence of Sporadic Colorectal Cancer, High Level of Microsatellite Instability, and Loss of Heterozygosity at Chromosome 18q. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum 2004, 47, 1467-1482, 10.1007/s10350-004-0628-6.

- Sanjay Popat; Richard S. Houlston; A systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between chromosome 18q genotype, DCC status and colorectal cancer prognosis. European Journal of Cancer 2005, 41, 2060-2070, 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.039.

- Sanay Popat; Dongbing Zhao; Zhengming Chen; Hongchao Pan; Yongfu Shao; Ian Chandler; Richard S Houlston; Relationship between chromosome 18q status and colorectal cancer prognosis: A prospective, blinded analysis of 280 patients. Anticancer Research 2007, 27, 627–633, .

- Anan H. Said; Jean-Pierre Raufman; Guofeng Xie; The Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2014, 6, 366-375, 10.3390/cancers6010366.

- A J Munro; S Lain; D P Lane; P53 abnormalities and outcomes in colorectal cancer: a systematic review. British Journal of Cancer 2005, 92, 434-444, 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602358.

- Marla Lay; Rajan Mariappan; Jason Gotlib; Lisa Dietz; Siby Sebastian; Iris Schrijver; James L. Zehnder; Detection of the JAK2 V617F Mutation by LightCycler PCR and Probe Dissociation Analysis. The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics 2006, 8, 330-334, 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.050130.

- Lee A. Albacker; Jeremy Wu; Peter Smith; Markus Warmuth; Philip J. Stephens; Ping Zhu; Lihua Yu; Juliann Chmielecki; Loss of function JAK1 mutations occur at high frequency in cancers with microsatellite instability and are suggestive of immune evasion. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0176181, 10.1371/journal.pone.0176181.

- Daniel Sanghoon Shin; Jesse M. Zaretsky; Helena Escuin-Ordinas; Angel Garcia-Diaz; Siwen Hu-Lieskovan; Anusha Kalbasi; Catherine S. Grasso; Willy Hugo; Salemiz Sandoval; Davis Y. Torrejon; et al. Primary Resistance to PD-1 Blockade Mediated by JAK1/2 Mutations. Cancer Discovery 2016, 7, 188-201, 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-16-1223.

- Gershon Y. Locker; Stanley Hamilton; Jules Harris; John M. Jessup; Nancy Kemeny; John S. Macdonald; Mark R. Somerfield; Daniel F. Hayes; Robert C. Bast Jr; ASCO 2006 Update of Recommendations for the Use of Tumor Markers in Gastrointestinal Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2006, 24, 5313-5327, 10.1200/jco.2006.08.2644.

- Won-Suk Lee; Jeong-Heum Baek; Keon Kuk Kim; Yeon Ho Park; The prognostic significant of percentage drop in serum CEA post curative resection for colon cancer. Surgical Oncology 2012, 21, 45-51, 10.1016/j.suronc.2010.10.003.

- Bin-Bin Su; Role of serum carcinoembryonic antigen in the detection of colorectal cancer before and after surgical resection. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2012, 18, 2121-2126, 10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2121.

- Volkan Tumay; Osman Serhat Guner; The utility and prognostic value of CA 19-9 and CEA serum markers in the long-term follow up of patients with colorectal cancer. A single-center experience over 13 years. Annali Italiani di Chirurgia 2020, 91, 494–503, .

- Andreas Jung; Thomas Kirchner; Liquid Biopsy in Tumor Genetic Diagnosis. Deutsches Aerzteblatt Online 2018, 115, 169-174, 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0169.

- Irma G. Domínguez-Vigil; Ana K. Moreno-Martínez; Julia Y. Wang; Michael H. A. Roehrl; Hugo A. Barrera-Saldaña; The dawn of the liquid biopsy in the fight against cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 2912-2922, 10.18632/oncotarget.23131.

- Leroy Hood; Systems Biology and P4 Medicine: Past, Present, and Future. Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal 2013, 4, e0012, 10.5041/rmmj.10112.

- Aifric O'sullivan; Bethany Henrick; Bonnie Dixon; Daniela Barile; Angela Zivkovic; Jennifer Smilowitz; Danielle Lemay; William Martin; J. Bruce German; Sara Elizabeth Schaefer; et al. 21st century toolkit for optimizing population health through precision nutrition. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2017, 58, 3004-3015, 10.1080/10408398.2017.1348335.

- Hossein Taghizadeh; Gerald W. Prager; Personalized Adjuvant Treatment of Colon Cancer. Visceral Medicine 2020, 36, 397-406, 10.1159/000508175.

- Sakti Chakrabarti; Hao Xie; Raul Urrutia; Amit Mahipal; The Promise of Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) in the Management of Early-Stage Colon Cancer: A Critical Review. Cancers 2020, 12, 2808, 10.3390/cancers12102808.

- Lynette M. Sholl; Geoffrey R. Oxnard; Cloud P. Paweletz; Traditional Diagnostics versus Disruptive Technology: The Role of the Pathologist in the Era of Liquid Biopsy. Cancer Research 2020, 80, 3197-3199, 10.1158/0008-5472.can-20-0134.

- Tiantong Wu; Yali Mo; Chengtang Wu; Prognostic values of CEA, CA19-9, and CA72-4 in patients with stages I-III colorectal cancer. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology 2020, 13, 1608-1614, .

- Wen-Sy Tsai; Jinn-Shiun Chen; Hung-Jen Shao; Jen-Chia Wu; Jr-Ming Lai; Si-Hong Lu; Tsung-Fu Hung; Yen-Chi Chiu; Jeng-Fu You; Pao-Shiu Hsieh; et al. Circulating Tumor Cell Count Correlates with Colorectal Neoplasm Progression and Is a Prognostic Marker for Distant Metastasis in Non-Metastatic Patients. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 24517-24517, 10.1038/srep24517.

- Hiroki Osumi; Eiji Shinozaki; Kensei Yamaguchi; Circulating Tumor DNA as a Novel Biomarker Optimizing Chemotherapy for Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 1566, 10.3390/cancers12061566.

- Rabih Said; Nicolas Guibert; Geoffrey R. Oxnard; Apostolia M. Tsimberidou; Circulating tumor DNA analysis in the era of precision oncology. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 188-211, 10.18632/oncotarget.27418.

- Zhen Wang; Jun-Qiang Chen; Jin-Lu Liu; Lei Tian; Exosomes in tumor microenvironment: novel transporters and biomarkers. Journal of Translational Medicine 2016, 14, 1-9, 10.1186/s12967-016-1056-9.