3.1.1. Genetic Diseases

The genetic conditions related to infertility, including the common and rare ones, account for almost 50% of all infertility causes [

6,

7]. In the presence of high suspicion of a genetically based infertility (such as malformations, recurrent abortions, and family history), according to the signs and symptoms observed by the specialist during the medical examination, a genetic test can provide a more accurate diagnosis of infertility and inform the couple about the risk of transmission of genetic defects to the offspring [

8].

In men, alterations in the standard semen analysis are the first indication for genetic tests, particularly in cases of severe oligospermia (<5 million/mL) [

9]. Although genetic factors have been identified in all the etiological categories of male fertility (pre-testicular, testicular and post-testicular), the main genetic tests routinely used for the diagnosis of male infertility are limited to the karyotype, the study of chromosome Y microdeletions and the analysis of the

CFTR gene [

6]. Genetic disorders related to male infertility include whole chromosomal aberrations (structural or numerical), partial chromosomal aberrations (i.e., microdeletions of the Y chromosome) and monogenic diseases [

10]. In particular, abnormalities in sex chromosomes have a greater impact on spermatogenesis, while mutations affecting autosomes are more related, for example, to hypogonadism, teratozoospermia or asthenozoospermia and to familial forms of obstructive azoospermia. Klyneferter syndrome (47, XXY) and Double Y syndrome (47, XYY) are the most frequent chromosome aneuploidies related to male infertility [

11,

12]. Individuals carrying these chromosomal alterations not only have a reduced fertility, but also shows an increased risk of abortion and having a child with karyotype alterations [

6]. Among the partial chromosomal alterations, microdeletions in the long arm of Y chromosome, involving the so-called azoospermia factor (AZF) region, are the most common genetic causes of male infertility [

13]. Indeed, the AZF region includes genes involved in the spermatogenesis, so that their deletion is related to an impaired reproductive capacity. In addition to chromosomal aberrations, more than 200 genetic conditions related to male infertility are reported in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man database (OMIM), ranging from the most common clinical presentations of infertility to the rarest complex syndromes [

14]. The search for pathogenic mutations in one or more genes should be evaluated based on patients clinical phenotypes. For instance, congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (CHH) is a rare endocrine disease featured by a deficient gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) activity due to both defective synthesis or peripheral resistance [

15]. CHH clinical phenotypes range from complete and more severe forms with the absence of puberty, to late-onset hypogonadism. To date, more than 30 genes have been related to this condition and their testing should be considered in male with CHH, after the exclusion of secondary forms [

16]. Similarly, the congenital absence of vas deferens (CAVD) may be both an atypical presentation of cystic fibrosis or an isolated reproductive disease. Thus, the

CFTR gene mutations screening is recommended in male patients with CAVD and, since novel candidate genes are emerging for the isolated forms, it may be useful to enlarge the molecular screening to include them [

17]. Altered sperm features, as assessed by semen analysis, may be due to rare diseases inherited as recessive traits. Within this category: macrozoospermia is a condition featured by large-headed and multiflagellated spermatozoa due to alterations of spermatozoa meiotic division; globozoospermia is a rare disease characterized by round-headed spermatozoa without acrosome; acephalic spermatozoa is a rare disease featured by the presence of headless spermatozoa; and multiple morphological abnormalities of the sperm flagella is another rare condition featured by morphological alterations affecting sperm flagella [

16]. One or more causative genes have been identified for all these rare inherited diseases. Their testing should be considered based on semen parameters [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Moreover, the Kartagener syndrome or primary ciliary dyskinesia is a rare genetic disease featured by abnormal internal organs position, high frequency of respiratory infections and asthenozoospermia, as a consequence of motility defects of both cilia and flagella [

22]. In this disease, sperm analysis usually doesn’t show morphological alterations, but spermatozoa have several structural abnormalities due to dyneins loss and microtubular rearrangements. About 30 genes have been related to Kartagener syndrome,

DNAI1 and

DNAH5 accounting for up to 30% of cases [

23,

24]. Mutations in the cation channel of sperm (

CATSPER) genes cause asthenozoospermia due to the incapacity of sperm to undergo hyperactivated motility during sperm capacitation [

25]. Additionally, androgen receptor (

AR) mutations have been related to male infertility issues [

26]. To date, more than 1000

AR mutations have been identified and associated with different phenotypes of androgen insensitivity syndrome, ranging from severe to mild forms [

26]. Finally, novel candidate genes are emerging due to the diffusion of next generation sequencing-based analyses and whole exome sequencing screening. Once the effects of these genes (and consequently of their mutations) in reproduction will be functionally assessed, their molecular testing may improve infertile men clinical management [

16].

In females, fewer specific tests are routinely recommended to identify chromosomal and genetic alterations that could interfere with healthy reproduction, i.e., karyotype analysis and genetic test for

FMR1/

FMR2 (Fragile X Mental Retardation 1 and 2) are advisable in case of fertility impairment. The

FMR1 premutation (the number of CGG repeats falls between 55 and 200) or

FMR2 microdeletions are related in females with menstrual dysfunction, diminished ovarian reserve and premature ovarian failure [

27,

28]. Several chromosome aberrations have been associated with female infertility, which primarily involves oogenesis. Turner syndrome (45, X0) and X chromosome cytogenetic alterations, including both reciprocal (exchange of two-terminal segments from different chromosomes) or Robertsonian (centric fusion of two acrocentric chromosomes) translocations, can cause blockage of meiosis resulting in primary ovarian insufficiency. In particular, reciprocal translocations are related to a significantly increased risk of infertility (i.e., hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with primary or secondary amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea), as balanced rearrangements can become a cause of multiple miscarriages [

29]. Thousands of genes are involved in human reproduction, about 200 of which have been related to infertility since they are able to affect specific steps required to this process [

30]. For instance, genetic causes of gonadal disgenesis have been identified. In this context, the Swyer syndrome is a defect of sex determination occurring in XY individuals showing a female phenotype with gonadal dysgenesis, absence of pubertal development, primary amenorrhea and infertility [

31]. Several molecular alterations have been related to this syndrome: about 15% of the patients carry pathogenic mutations in the

SRY gene but Y chromosome structural alterations, or mutations in other genes, such as

NR5A1,

NR0B1,

WNT4,

AR,

MAP3K1,

GATA4,

DMRT1,

DMRT2,

ZNRF3, and

DHH, have been also reported [

30]. Another gonadal alteration is the ovarian dysgenesis occurring in XX individuals showing an impaired ovarian development. About 10 different genes have been implicated in this process and their defective functions may impair gonadal development leading to the onset of a wide spectrum of clinical phenotypes, including isolated and syndromic conditions, associated with complete gonadal dysgenesis and less severe forms of primary ovarian insufficiency [

32,

33]. Further, defects of early oogenesis have been related to female infertility. Indeed, an increased cell death rate causes the depletion of the follicle pool, incomplete follicles development, altered sexual differentiation and gonadal dysgenesis. Mutations in more than 30 genes implicated in meiosis, germ cells mitosis and DNA damage repair have been described as related to oogenesis alterations and their testing may be evaluated based on patients clinical signs taking into account that these mutations have been identified in patients with idiopathic infertility and a positive history for recurrent abortions [

30,

34]. Moreover, it is well established that chromosomal segregation errors during meiosis occur more frequently with the increase of women age [

35]. These age-related aneuploidies, and consequent infertility, have been associated with the progressive loss of cohesins proteins, such as SGO2 [

36]. Mutations in genes involved in mitotic checkpoints, like

BUB1B and

CEP57, can lead to multiple chromosomal alterations resulting in defective oocytes maturation, embryonic death and miscarriages [

37,

38]. Several studies have highlighted the role of genes involved in DNA repair in follicles maturation and quality, reproductive aging and the age at menopause [

30]. Indeed, these genes play a role both in meiosis and mitosis and can cause variable phenotypic expression, including syndromic conditions featured by growth retardation, developmental defects, endocrine disorders, gonadal alterations and increased susceptibility to cancers development [

30]. In addition, mutations in

MCM8,

MCM9,

XRCC4, and

MSH5 are able to induce a non-syndromc primary ovarian insufficiency [

39]. Altered folliculogenesis is another pathogenetic mechanism underlying female infertility and also in this case several genetic alterations have been identified so far. Indeed, a woman’s reproductive life depends on the number of primordial follicles, their quality and germ cell depletion [

39].

GDF9 and

BMP15 gene variants, have been identified in about 10% of women with hypergonadotropic ovarian failure, primary ovarian insufficiency, amenorrhea, and polycystic ovary syndrome [

40]. Similarly, mutations in multiple oocyte-specific transcription factors (such as

FIGLA,

NOBOX,

LHX8,

SOHLH1, and

SOHLH2), being involved in follicular development and future embryonic activation, have been found to be associated with ovarian dysgenesis and primary ovarian insufficiency [

32]. Interestingly, primary ovarian insufficiency has been described in different syndromic conditions, such as Perrault syndrome, epicanthus inversus syndrome, blepharophimosis with ptosis, leukoencephalopathy with vanishing white matter, galactosemia and carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndromes [

30]. Moreover, also mutations in the mitochondrial

POLG gene have been identified in women with primary ovarian insufficiency [

41]. Folliculogenesis, oocytes maturation, ovulation and implantation are regulated by the action of the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH); thus, mutations affecting their corresponding genes are able to lead to fertility impairment. Indeed, women carrying mutations in

FSHB and

FSHR genes result respectively in hypogonadotropic and hypergonadotropic hypogonadism [

42,

43]. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism is a rare disease due to GnRH deficiency resulting in incomplete or absent puberty and infertility, and associated with more than 25 causative genes [

44,

45]. Furthermore, female-specific factors affecting genes involved in sperm capacitation and the sperm’s ability to penetrate the zona pellucida cause fertilization failure and infertility [

46]. Finally, as for male, next generation sequencing approaches are allowing the identification of an increasing number of genetic variants associated with female infertility, thus suggesting their possible use as genetic biomarkers for infertility.

Although our knowledge of infertility’s molecular bases is continually growing, genetic tests for male and female infertility suffer from an ineffective approach in clinical practice. An in-depth analysis using a targeted genetic test, chosen after an accurate evaluation of the medical and familial history, could identify a specific genetic disease thus allowing a personalized diagnostic and therapeutic management (i.e., fertilization with donor, preimplantation genetic diagnosis, etc.) [

8]. To date, the development of sequencing technologies has encouraged the use of gene panels, which have proven helpful companion diagnostics for different pathologies [

47,

48,

49]. The European Society of Human Genetics (ESHG) and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) have recently issued a recommendation for the introduction of targeted multigene panels, as expanded carrier screening [

50,

51]. Genetic tests based on parallel sequencing of several genes facilitate the process of gene investigation in infertility, reducing diagnostic costs and time [

8], decreasing the current 20% rate of idiopathic infertility, and characterizing the different subtypes of male and female infertility [

7,

52].

The general state of health in reproduction is gaining increasing attention and clinical relevance. Therefore, infertile couples must be evaluated considering the aspects of public and psychological health, as well as the reproductive element, since the relative conditions of comorbidity can influence their reproduction. This will allow changing couples’ management, moving from a population-based view to an individual-based one. For example, numerous studies show that the difference in the response to therapy found among patients, may be due to specific DNA variations; thanks to genetic characterization, the clinicians are now able to choose the most appropriate approach for the prevention or treatment of the condition in individual patients and infertile couples [

17,

53,

54].

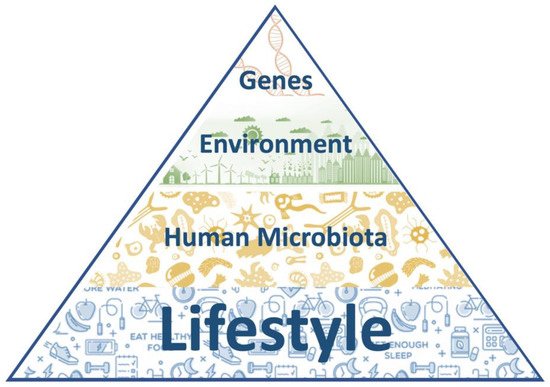

Outside of particular hereditary diseases, the idea of a single “responsible gene” for traits or diseases is rarely viable. In most cases, there are hundreds, thousands of genes that contribute to a complex trait, such as reproduction. To identify fertility-related genetic variants and genomic loci, more than 70 genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been carried out analyzing multiple samples and more than 30 traits associated to reproduction have been found [

55]. In this context, Barban et al. [

56], analyzing about 700,000 individuals, identified 12 loci associated with reproductive behavior highlighting also candidate genes and potentially causal variants [

56]. Recently, Loizidou et al. [

57] assessed in a Ukainian cohort an association between 12 genetic loci and recurrent pregnancy loss [

57]. In addition to the possibility to discover novel candidate genes and mutations, these GWASs on common genetic risk factors provide novel clues to interpret the underlying relationships and causality involved in the regulation of reproduction and fertility. These data will allow to achieve new insights into disease risk, disease classification and co-morbidity for many diseases associated with reproduction alterations and infertility. Moreover, while the study of genetics has brought under the spotlight the importance of gene mutations in the probability of procreating, other factors have also been considered as pivotal and have gained the attention of several studies in the scientific community.

3.1.2. Autoimmunity

Autoimmune diseases (ADs) are characterized by multi-system involvement, and a mounting body of evidence points to their impact on both fertility and pregnancy. ADs are easily overlooked as they can be clinically silent or present with non-specific symptoms and continue to remain undiagnosed until a severe complication is encountered. ADs affect different stages of female fertility, such as ovarian reserve, fertilization, and implantation. About 10–30% of women with premature ovarian failure have an AD, the most common being systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, and autoimmune thyroid diseases [

58]. In these disorders, autoantibodies are produced against steroid-producing cells resulting in oophoritis and immune cells infiltration of pre-ovulatory follicles and corpus luteum [

58,

59]. In SLE, a prolonged inflammation causes dysfunction of the hypothalamus-pituitary-ovarian axis resulting in menstrual irregularities; moreover, SLE medical therapies, such as high dose of steroids and immunosuppressive drugs, also impair fertility [

58,

59].

Auto-immune thyroid diseases are characterized by high titers of anti-thyroglobulin and anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies. Monteleone et al. [

60] demonstrated the presence of thyroid autoantibodies in the follicular fluid, and their levels strongly correlated with serum concentrations. They proposed that these antibodies bind to antigens expressed in the zona pellucida, damaging the maturing oocytes, and reducing both the fertilization and implantation rates [

60]. A meta-analysis evaluating the impact of thyroid autoimmunity on in vitro fertilization (IVF)/intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), found that the fertility rate was not affected suggesting that ICSI could overcome the negative impact of thyroid autoantibodies [

61].

Auto-immune mechanisms have also been described in endometriosis, a well-known condition associated with infertility. Indeed, IgG antibodies directed to laminin-1, and thus affecting the implantation process, have been found in patients with endometriosis [

58,

62]. Similarly, antiphospholipid antibodies (APL) also affect implantation, placentation, and early embryonic development, thus impairing fertility [

58,

62]. Finally, ADs like type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM) have been associated with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) that reduces fertility by causing multiple endocrine dysfunctions [

58].

ADs have been reported to affect also pregnancy outcomes, recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) being one of the dreaded complications of ADs. Mumusoglu et al. [

63] observed a significantly higher frequency of RPL in the autoantibody-positive women than controls, and the RPL ratio positively correlated with autoantibodies concentration [

63]. Among the different autoantibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies (APL) showed a higher association with RPL. The degree of association varies with the type of APL, among which Lupus anticoagulant and IgG anticardiolipin antibodies were found to be the most significant [

63]. It has been proposed that this phenomenon may be due to the ability of APL to disrupt adhesion molecules between the trophoblast cells, to damage the trophoblast through the action of cytokines, and to increase the risk of placental thrombosis [

58,

64]. An increased risk of miscarriage and RPL in women with positive thyroid autoantibodies has been demonstrated in both natural and IVF pregnancies [

61,

62]. Indeed, the generalized immune imbalance and the diminished thyroid reserve caused by thyroid autoantibodies decrease the ability of the thyroid gland to adapt to the physiological changes due to pregnancy. These effects are amplified in IVF pregnancies due to the harmful impact of ovarian stimulation on thyroid function. Late pregnancy complications have been also associated to ADs, including eclampsia, oligohydramnios, intrauterine growth restriction, stillbirth, and preterm deliveries [

59,

62,

63,

64]. Moreover, anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies are associated with neonatal lupus and isolated congenital heart block in babies born to mothers with ADs [

59,

64].

Though ADs are more common in women, also men’s fertility may be affected by these disorders. In particular, anti-sperm antibodies (ASA) are auto-antibodies targeting the seminiferous tubules and are responsible for autoimmune orchitis. ASA are able to affect several sperm features, including sperm motility, penetration of cervical mucus and migration through tubes. Moreover, they affect sperm capacitation and acrosome reaction, thus interfering with sperm-oocyte interaction and ultimately preventing the implantation of the embryo and its further development [

65]. In addition to ASA, secondary orchitis caused by testicular vasculitis observed in other ADs, like SLE, rheumatoid arthritis and polyarteritis nodosa, may have similar effects on male infertility [

65].

Knowledge about the impact of ADs on fertility is essential since their complications are preventable with timely diagnosis and appropriate therapy. As ADs are notable for silent and/or non-specific clinical signs, a high index of suspicion helps to diagnose them at an early stage. Early diagnosis provides the benefit of initiating appropriate treatment and close monitoring to prevent potential complications.