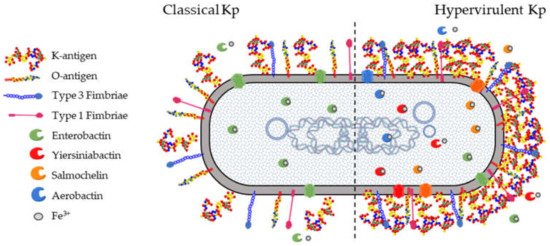

All Kp isolates carry a set of core genes responsible for their pathogenicity and required to establish opportunistic infections in humans and other hosts (). These include the K-antigen locus (cps locus) and the O-antigen locus (rfb locus), collectively involved in immune evasion mechanisms. The core fim and mrk loci are responsible for the biosynthesis of type 1 and type 3 fimbriae which mediate processes in the earlier stages of infection, such as adhesion and colonization of host epithelia as well as biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces such as catheters. Finally, the ent locus encoding the siderophore enterobactin, as well as alternative acquired siderophores, is required for optimal growth in different niches.

2.1. K-Antigens

The surface of

Klebsiella species is shielded by a thick layer of capsular polysaccharide, historically known as K-antigen, that protects the bacteria from the environment as also observed in

E. coli [

59]. K-antigens play a crucial role in protecting Kp from innate immune response mechanisms, evading complement deposition and opsonization, reducing recognition and adhesion to epithelial cells and phagocytes, and abrogating lysis by antimicrobial peptides and the complement cascade [

60].

Traditionally, 77 K-antigens have been identified among

Klebsiella spp. based on the diversity in their sugar composition, type of glycosidic linkages, and the nature of enantiomeric and epimeric forms [

61,

62]. Recently, additional K-types have been reported based on the arrangement of the

cps locus or K-locus (KL), known as the KL series [

56].

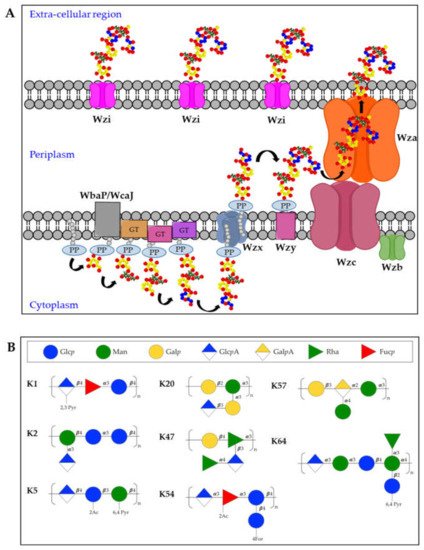

The K-antigen biosynthesis occurs via the Wzx/Wzy-dependent pathway, similarly to group 1 capsules in

E. coli [

63,

64]. The

cps locus comprises two regions: the 5′ part of the locus contains four conserved genes (

wzi,

wza,

wzb, and

wzc), present in all group 1 capsule loci. The 3′ region of the locus is serotype-specific and encodes the enzymes for producing the repeating units and two integral inner membrane proteins (Wzy and Wzx) [

65]. In particular, capsules biosynthesis takes place in the cytoplasmic leaflet of the inner membrane where the repeating units are assembled on the lipid carrier undecaprenol-pyrophosphate (Und-PP), with the contribution of sugar-specific glycosyltransferases. In particular, the specific initialization glycosyltransferase can either be WbaP (generating galactose-Und-PP) or WcaJ (generating glucose-Und-PP) [

66]. Next, the Wzx flippase transfers the complete repeating units to the periplasmic leaflet of the inner membrane where the Wzy polymerase generates high molecular weight polysaccharides. Finally, Wza (an outer-membrane translocon), Wzc (a tyrosin autokinase) and Wzb (a phosphatase) synergistically transport the complete capsule onto the bacterial surface, where it remains associated to the outer-membrane protein Wzi (a lecto-aqua-porin) [

62] (A).

Figure 2. (A) Model for biosynthesis and assembly of group 1 capsules. Undecaprenol-pyrophosphate (Und-PP)-linked repeating units are assembled on the cytoplasmic leaflet of the inner membrane. Wzx then flips the newly synthesized und-PP-linked repeats across the inner membrane. In the periplasmic leaflet of the inner membrane, Wzy polymerizes the repeating units. Continued polymerization requires transphosphorylation of the Wzc oligomer and dephosphorylation by the Wzb phosphatase. Finally, the polysaccharide is translocated by Wza in the extracellular milieu where it associates with the surface protein Wzi. PP = Undecaprenyl diphosphate, GT = glycosyltransferase. (B) Structures of K-antigens most commonly associated to Hv-Kp strains.

Among the different K-antigens, K1, K2, K5, K16, K23, K27, K28, K54, K62 and K64 are some of the most commonly isolated serotypes globally [

54]. Interestingly, K1 and K2 serotypes are often found in Hv-Kp strains, indicating that this clonal lineage has a specific genetic background conferring hypervirulence [

67,

68] (B). Moreover, Hv-Kp strains are known to produce a hypercapsule, resulting in a hypermucoviscous phenotype which further contribute to increased resistance to complement-mediated or phagocyte-mediated killing [

69]. The

rmpA gene was first identified as a regulator of the mucoid phenotype in 1989 [

70], located either on the chromosome or on a large virulence plasmid. The correlation between

rmpA (or the closely related

rmpA2 gene) and hypermucoid phenotype is very high, and the presence of

rmpA is among a set of genes proposed as biomarkers to identify potential Hv-Kp strains [

29,

71]. Other capsule types which are frequently found among Hv-Kp strains are K5, K20, K47, K54, K57, and K64 [

29,

72,

73] (B).

2.2. O-Antigens

The O-antigen moiety of the LPS has a limited range of structures, resulting from different sugar composition, glycosidic linkages, epimeric or enantiomeric forms of the sugars [

54,

74]. The nomenclature of O-serotypes has been revised multiple times over the years [

75,

76], however, the most recent classification includes 11 O-serotypes: O1, O2a, O2ac, O2afg, O2aeh (previously known as O9), O3 (divided in sub-serotypes O3, O3a and O3b), O4, O5, O7, O8 and O12 [

56]. Moreover, additional O-types have been reported based on the arrangement of the

rfb locus or O-locus (OL), known as the OL series.

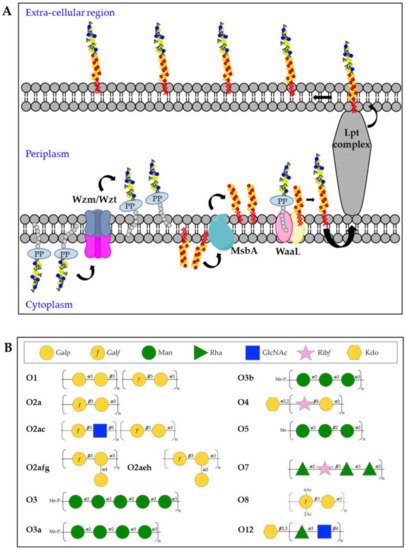

Kp O-antigens are biosynthesized in the cytoplasm and transported to the bacterial surface through an adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette (ABC) transporter dependent-pathway [

77] (A). In detail, the O-antigen is synthesized in the cytoplasmic leaflet of the inner membrane by serotype-specific glycosyltransferases and transferred to the periplasmic leaflet by the Wzm/Wzt complex. In parallel, the biosynthesis of the lipid A-core oligosaccharide also takes place in the cytoplasmic leaflet of the inner membrane and the sugars are then flipped to the periplasmic leaflet through the MsbA transporter. Finally, the polymerized O-antigen and lipid A-core oligosaccharide are linked by the WaaL ligase and the LptA-G complex transports the complete LPS to the bacterial surface [

62]. In the whole process, three different gene clusters are involved:

lpx,

waa and

rfb for the biosynthesis of lipid A, core-oligosaccharide and O-antigens, respectively [

78,

79,

80].

Figure 3. (A) Model of O-antigen biosynthesis via the adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette (ABC) transporter pathway. Und-PP-linked O-polyaccharides are processively assembled on the cytoplasmic leaflet of the inner membrane, through the sequential activity of different glycosyltransferases. The assembled O-antigen component is then transported via the Wzm/Wzt ABC transporter across the inner membrane. In the periplasmic leaflet of the inner membrane, the O-antigen is ligated to the lipid A-core oligosaccharide by WaaL and finally transported on the bacterial surface by the Lpt complex. (B) Structures of Kp O-antigens.

The O1, O2 and O8 serotypes are galactose-based polysaccharides and they share a common backbone named O2a (also known as Galactan-I) characterized by the [→3)-α-D-Gal

p-(1 → 3)-β-D-Gal

f(1→] repeating unit (B). The biosynthesis of the O2a antigen is attributed to the

rfb locus involving

wzm,

wzt,

wbbM,

glf,

wbbN, and

wbbO genes [

81]. The O2 serotype includes different variants, represented by modified versions of the O2a backbone. The O2afg and O2aeh (O9) serotypes modify the O2a repeating unit by side-chain addition of (α-1 → 4)- or (α-1 → 2)-Gal

p residues catalyzed by a set of three enzymes encoded by genes

gmlABC and

gmlABD, respectively [

82]. The O8 serotype modifies the O2a repeating unit by non-stoichiometric O-acetylation [

83] (B). The O1 serotype results from the covalent attachment of the O1 antigen (also known as Galactan-II) to the non-reducing terminus of O2a (as well as O2afg and O2aeh) and is characterized by the immunodominant [→3)-α-D-Gal

p-(1→3)-β-D-Gal

p-(1→] repeating unit, which has been associated to the

wbbY-wbbZ genes [

84] (B). The O2c antigen can also be covalently attached to the non-reducing terminus of O2a (as well as O2afg and O2aeh), resulting in serotype O2ac: this is characterized by the immunodominant [→3)-β-D-Glc

pNAc-(1 → 5)-β-D-Gal

f-(1→] repeating unit, which has been associated to the

wbmVWX genes [

84] (B).

The O3 and O5 serotypes are mannose-based saccharides and their structures are identical to the

E. coli O9 and O8 O-antigens, respectively [

85,

86] (B). Biosynthetic enzymes of O3 and O5 are extremely similar but differ in the sequence of their mannosyltransferase (WbdA) and methyltransferase (WbdD). WbdD, in complex with WbdA, regulates the mannose chain length by capping the growing chain with a phosphate and methyl group in O3 and a methyl group only in O5 [

87,

88]. Therefore, the O3 and O5 repeating units differ from each other in the number of mannoses, anomeric configurations and/or their intra-mannose linkages [

89]. In particular, the trimeric O5 repeating unit is composed of α-mannose (α-Man) and β-mannose (β-Man) with 1 → 2 and 1 → 3 linkage, whereas O3 uses pentameric 1 → 2- and 1 → 3-linked α-Man repeating units [

89]. In addition, two Kp O3 serotype variants, O3a and O3b, have been identified with only four α-Man residues (O3a) or three α-Man residues (O3b), instead of five α-Man residues per repeating unit [

90] (B).

The O4, O7 and O12 serotypes are very different to the other O-antigens for their repeating units sugar composition (B). The Kp O4 repeating unit is characterized by the disaccharide [→4)-α-D-Gal

p-(1 → 2)-β-D-Rib

f-(1→], the O7 by a tetrasaccharide [→2)-α-L-Rha

p-(1 → 2)-β-D-Rib

f-(1 → 3)-α-L-Rha

p-(1 → 3)-α-L-Rha

p-(1→] while the O12 by the disaccharide [→4)α-L-Rha

p-(1 → 3)-β-D-Glc

pNAc-(1→] [

89]. In addition, it was found that the O4 and O12 O-antigen chains terminate with Kdo residues.

2.3. Fimbriae

The majority of Gram-negative enterobacteria differentially express surface-associated fimbriae, organelles appointed to facilitate attachment and adherence to eukaryotic cells, but also involved in other functions, such as interaction with macrophages, biofilm formation, intestinal persistence, and bacterial aggregation [

91,

92,

93]. Fimbriae are typically extracellular appendages with 0.5–10 μm length and 2–8 nm width. Most clinical Kp isolates express two types of fimbrial adhesins, type 1 fimbriae and type 3 fimbriae, that are assembled by the chaperone/usher-assembly pathway [

94,

95,

96]. Besides type 1 and type 3 fimbriae, a third type named KPC fimbria was identified and the heterologous expression in

E. coli demonstrated an active role of this protein in biofilm formation [

97]. Since the late 1990s, another Kp fimbrial antigen named KPF-28 has been reported to be expressed by several Kp circulating strains and its role in colonization has been demonstrated by using KPF-28 antisera to inhibit bacterial adhesion to intestinal cells. However, besides a correlation of the expression of this adhesin with an antibiotic-resistance phenotype, no further information has been collected about KPF-28 over the last two decades [

98,

99].

Type 1 fimbriae are 7 nm wide and approximately 1 µm long surface polymers found on the majority of

Enterobacteriaceae and encoded by the genes in the

fimAICDFGHK operon. This organelle is a helical cylinder that belongs to the chaperon-usher pili family, made by a polymer of the major building element FimA. FimH, together with the minor subunits FimF and FimG, forms a flexible tip fibrillum that is connected to the distal end of the pilus rod and that is responsible of the adhesion to the host [

100,

101,

102,

103]. FimH recognizes mannosylated glycoproteins, including those present on the host urinary epithelium as demonstrated by using D-mannose or oligosaccharides containing terminal mannose residues in FimH-mediated adhesion inhibition experiments [

104,

105].

Type 1 fimbriae were described to be phase-variable with a different role in lungs and urinary or intestinal tract infections. Indeed, fimbrial expression was found to be highly upregulated in the bacterial population in urine and infected bladders and downregulated in the lungs. In this organ, expression of type 1 fimbriae may be a disadvantage for the bacteria because of their ability to adhere to phagocytic cells in the lungs and therefore to be rapidly eliminated [

106,

107,

108]. Moreover, FimH was shown to be required for Kp invasion and biofilm formation in a murine model of UTI [

109] but the role of type 1 fimbriae in colonization of the gastrointestinal tract still remains controversial. Indeed, while Jung et al. observed the decreased colonization ability of a Kp

fimD mutant of antibiotic-treated mice intestine (FimD is appointed to facilitate assembly and translocation of the pilus), another recent work showed data supporting that type 1 fimbriae do not contribute to gastrointestinal colonization as no significant difference in adhesion was noticed between wild-type and

fimH mutant strains [

110,

111].

The components of type 3 fimbriae are encoded by the genes in the

mrkABCDF operon [

112,

113]. The

mrk gene cluster, as other fimbrial operons of the chaperone-usher class, contains genes encoding the chaperone (

mrkB), the usher (

mrkC) and the protein-based filament composed by a major (

mrkA) and a minor (

mrkF) subunit. MrkD is the tip adhesion protein, which is appointed for the adhesive properties of the whole complex, whereas to MrkE has been attributed a regulatory activity [

112,

114].

Among different

Klebsiella strains, it is possible to find a plasmid-borne determinant,

mrkD1P, and a chromosomally borne gene,

mrkD1C, which are not genetically related, and the proteins encoded have been shown to have differences in functionality. MrkD adhesin located within a chromosomally borne gene cluster mediates binding to collagen types IV and V, whereas only few strains presenting the plasmid-borne form showed collagen-binding activity [

115].

The presence of

mrk genes in multiple genomic locations, including conjugative plasmids or transposons, can explain why this operon is so widespread among Gram-negative bacteria [

116,

117].

Type 3 fimbriae have been extensively proven to mediate binding to extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins such as collagen molecules [

115,

118] and to strongly promote biofilm formation [

119,

120,

121].

A recent study revealed that MrkA expression was downregulated after treatment of Kp with the phytosynthesized silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) fabricated from

Mespilus germanica, as demonstrated by RT-PCR analysis. In correlation with MrkA expression, also a strong reduction in biofilm formation was observed following treatment with AgNPs, confirming once again the leading role played by MrkA in this process [

122]. Interestingly, investigation of MrkA regulation by Wilksch et al. has led to the understanding of another key player in type 3 fimbriae regulation, named MrkH, which directly activates transcription of the

mrkA promoter. MrkH strongly binds to the

mrkA regulatory region only in the presence of c-di-GMP, a second messenger molecule known to regulate the expression of many bacterial factors involved in colonization and biofilm formation [

123,

124,

125,

126,

127].