The introduction of the microscope by Marcello Malpighi, in the 17th century, constituted the most important revolution in the history of biology [1]. It allowed the subsequent discovery by Robert Hooke that organisms are made of ‘cells’ [2] and later of the existence of a great variety of cells in animals and plants [3,4].

The formation of organs from the folding, fusion and growth of the primordial germ layers was detailed by Caspar Friedrich Wolff [5] in 1774 in his thesis “Theoria Generationis”. For this, he is considered the father of embryology. Heinz Pander is credited with the description, in 1817, of the three germ layers (ectoderm, endoderm and mesoderm) in the developing chick embryo [6]. Subsequently, von Baer expanded this work and suggested that the three layers are common to all vertebrates [7].

During embryonic development, the ‘ectoderm’ gives rise to the skin and the nervous system; the ‘endoderm’ to the digestive tract and associated glands and the ‘mesoderm’, which develops between the endoderm and the ectoderm, gives rise to the coelom. The ‘intermediate mesoderm’, which is located between the paraxial mesoderm and the lateral plate mesoderm, gives rise to the urogenital structures (kidneys, gonads and genital tract).

During the first part of the 19th century, researchers identified the presence of an epithelium only on the inner surfaces of the uterus, cervix and Fallopian tubes. Identifying the presence of epithelium at ectopic sites was a gradual discovery that started with the study of unusual cystic lesions. The early lesions attracted attention because of their size and/or unusual macroscopic features. In most early accounts of these large uterine or pelvic cavitated lesions, a distinction was not made on whether they had a mucosal lining and reports focused on gross pathology. In many cases, specimens were not even subjected to histological examination.

2. Early Descriptions

Mostly, early reports dealt with descriptions of lesions of large or unusual macroscopic appearance, and not much attention was paid to symptoms. Cullen provided an initial account of his experience in 1919 [

13] and a more detailed account in 1920 [

14]. Cullen stated that adenomyomas can readily be diagnosed based on clinical grounds. However, in common with other gynecological affections, mucosal invasions (MI) may be asymptomatic, or associated with cyclical pelvic pain and infertility and, despite modern imaging techniques, in a majority of cases, it is not possible to arrive at a definitive diagnosis of MI without histological examination. Thus, a history of the discovery of MI is necessarily distinct from a narrative of how medicine or society addressed affections, or manifestations of diseases of women and should be linked to the use of histological proof of the presence of ectopic epithelial cells.

Our approach to the history of progress in understanding MI contrasts with that taken by Nezhat et al. [

15] who attempted to explore the social history of a variety of illnesses affecting women. Their approach creates difficulties, because of the non-specific symptoms linked to MI and because it ascribes to ancient physicians knowledge that they simply could not have had. Therefore, whether diseases caused by MI existed in the early days cannot be confirmed through identifying reports suggestive of women suffering pelvic pain. This means that, on the one hand, there is no reason to believe that diseases caused by MI did not affect women even millennia ago, on the other, it remains speculative whether modern lifestyles and other influences affected the incidence of MI. It is for this reason that endometriosis, which is one of the main MI, has been referred to as a ‘modern disease’ [

16]. MI have only been brought to medical attention through advances in diagnostics during the last part of the XIX and during the XX century.

Knapp [

17] reported that a number of dissertations dating back to the 17th and 18th centuries mentioned the morphological features of endometriosis, but these theses describe ulcers and inflammations of the uterus. Knapp believed that Daniel Schrön [

18] described endometriosis in 1690 when he reported ulcers on the peritoneum, bladder and elsewhere in the pelvis. It is conceivable that some of the lesions observed by Schrön were instances of MI, but he did not recognise them to be due to the presence of ectopic epithelial cells. In addition, he goes on to describe the lesions as pus-filled or forming abscesses rather than having the macroscopic appearance of a mucosal invasion. Similarly, Knapp stated that Crellius [

19] mentioned an ovarian endometriotic cyst in 1739 when he described a tumour adhering to the fundus of the uterus

(tumorem fundo uteri externe adherentem describit). These words do not entail a recognition of lesions featuring MI.

The wider use of microscopy enabled the recognition of mucosa-lined cysts and of microscopic gland-like structures in the lower peritoneal organs. The first such descriptions were made by Carl Rokitansky, who together with Rudolph Virchow are widely credited as the founders of pathological anatomy. Rokitansky performed microscopical examination of tissues, but this was not routine, or widely practiced at the time. In his manual, first published in 1849, Rokitansky [

20] included a reference to ‘chocolate containing cysts of the ovary’, but only as instances of simple cysts, which he attributed to the growth of Graafian follicles. He believed that the trigger for the growth of these cysts was a response to either an inflammatory process or

de novo growth. He also provided an account of the existence of uterine hypertrophy, but not of mucosal growths within the myometrium. In 1860, Rokitansky [

21] described the new formation of mucosal tissue in the uterus and ovaries and described tumours, or polyps, containing glands that were similar to uterine glands. He used the term ‘

sarcoma adenoids uterinum’ to refer to these new growths and the term ‘

cystosarcoma adenoids uterinum’ for lesions that contained cysts. An early description of cysts containing chocolate-like material was also provided by Spencer Wells [

22]. Twenty-five years after Rokitansky’s description, Gusserow [

23] may have been the first to refer to his work when he stated, in discussing fibroid polyps, that lesions containing glandular structures are better viewed as lesions of the mucosa.

3. The Term Adenomyoma

During the second half of the 19th century, the term ‘adenomyoma’ was coined to designate the majority of mucosa-containing lesions. According to Lockyer [

24], the first detailed description of an adenomyoma was made by Babeș (Victor Babesiu) [

25] who, in 1882, published a case of an intramural myoma containing cysts lined with ‘low cubical epithelium derived from embryonic germs’ and by Diesterweg [

26] who, in 1883, described ‘two polypi of the posterior uterine wall containing cysts lined with ciliated epithelium and filled with blood’. Both von Recklinghausen [

27,

28] and Cullen [

29] utilised the term ‘adenomyoma’ and they were followed by Pick [

30], Rolly [

31] and Iwanoff [

32].

Cullen [

33] and Lockyer [

24] quoted Breus [

34] as stating that, for their dissertations, Schröder, [

35], Heer [

36] and Grosskopf [

37] had collected more than 100 cases of adenomyomas from existing medical literature. However, these seemingly uncritical quotations overlooked the fundamental distinction that Breus made, based on whether cystic spaces observed within myomas had an epithelial lining. Breus emphasised that a mucosal lining was demonstrated in only four (possibly five) of all published cases, as the vast majority had not been subjected to microscopic examination or had no mucosal lining when examined. This was in agreement with Fritsch [

38] who argued that the presence of epithelial lining in these cystic spaces is very rare. To Breus, the cases described by Babeș [

25], Diesterweg [

26], Schröder and examined by Ruge [

39] were the only instances that had histologically proven mucosa-lined-cysts. Breus added two cases made available to him by Kundrat (Rokitansky’s successor) in Vienna.

Up to Breus’s report, published cases mostly dealt with gross lesions. For instance, one of the cases he described contained 7 liters of fluid, and the size of another was ‘that of a child’s head’. In the case described by Babeș [

25], there were two hazelnut-sized cysts in the uterus of a 91-year-old woman. Diesterweg [

26] described a tumour the size of a man’s fist containing cysts lined by ciliated epithelium. Thus, none of these reports fits with our current appreciation of uterine adenomyosis or endometriosis.

Real progress in recognising adenomyomas was made when Friedrich von Recklinghausen published two reports in 1893 and 1896 [

27,

28], describing 34 cases and including extensive histological examination (). He acknowledged the work of Rokitansky [

21], Kolb [

40], Röhrig [

41] and Babeș [

25] and concluded that MI should be divided based on whether the lesion was found at the periphery or centrally in the uterus and tubes. He described four varieties:

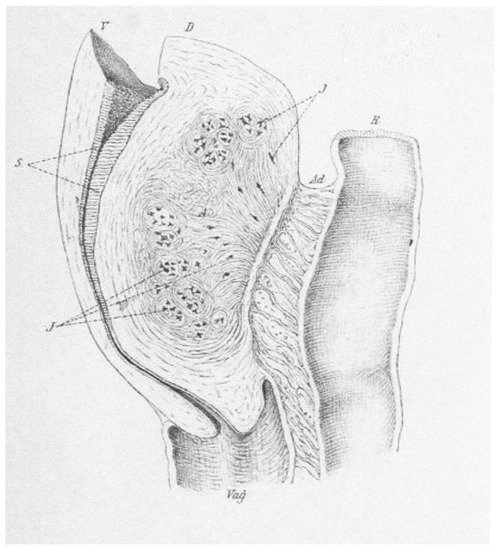

Figure 1. A median section of a hypertrophic uterus with adenomyosis in the posterior wall (D) but not affecting the anterior wall (V). Von Recklinghausen describes adenomyosis as a kidney-shaped adenomyoma containing glandular islets (J). There were adhesions (Ad) to the rectum (R). The endometrium (S) and the vagina (Vag) are shown. From von Recklinghausen (1896).

-

Hard: predominately made of muscle tissue.

-

Cystic: containing visible cystic spaces and equal glandular and muscle tissue.

-

Soft: predominately made of glandular tissue.

-

Telangiectatic: soft, very vascular growths that are almost devoid of cysts.

Von Recklinghausen classified glandular structures based on their architecture and epithelial type into straight, tortuous and round-ended. He viewed these as analogous to secreting tubules, ampullae and end-bulbs of Wolffian ducts. Fusion of the tubules formed canals, which were either discrete or aggregated (). Structural features and the observation that there were no glands in the fallopian tubes convinced him that adenomyoma originated from Wolffian duct structures.

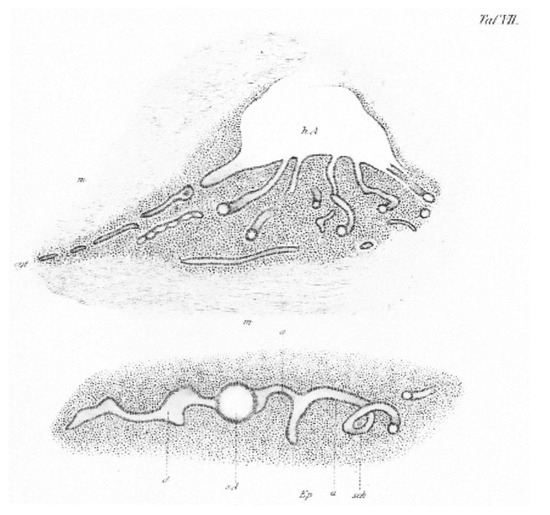

Figure 2. Example from von Recklinghausen’s (1896) histological study of uterine adenomyosis which he viewed as having similarities to the Wolffian duct structures. In the (top) von Recklinghausen demonstrates a main ampoule (hA) with raised and flattened epithelium on its roof and where the cytogenic connective tissue is completely lost. He views the six small canals at the bottom of the ampoule as probably collecting tubes with a leading canal on the left continuing in two fragments. He draws similarities to a collecting system. The (bottom) is viewed to depict a secretion tube (d) running from the left to connect to the spherical ampoule (sA) seen in the transverse section. This is seen to merge into the short collecting tube (a) running from the right and forming a looped section (sch).

Another major contributor to the recognition of adenomyoma of the uterus is Thomas Cullen, who presented his first case to the John Hopkins Hospital Medical Society in 1895 [

13]. This was shortly after he had completed his training in Germany and had taken up the position of head of gynecological pathology. Cullen added an important contribution to the field, published in German as a tribute to Johannes Orth of Göttingen [

42]. In this, he acknowledged the support of von Recklinghausen and described a number of known cases, including those by Paul Locksteadt who was able, through the introduction of Prussian Blue dye, to establish continuity between the glands in the myometrium and the uterine mucosa [

43].

The first case of an adenomyoma involving the round ligament was published by Cullen in 1896 [

29]. He refered to the histological features that include striations with scattered chocolate-coloured areas varying from 1 to 5 mm in diameter, as the characteristic features of adenomyoma. He observed that scattered endometrial glands were accompanied by a stroma.

In the book, Adenomyoma of the Uterus, published in 1908, Cullen [

33] referred to the first case he encountered during his clinical practice in 1894. The description is that of a uterus about four times the natural size with uniform, diffuse thickening of its anterior wall. He viewed it as most unusual and warranting histological examination. That revealed a diffuse myomatous tumor with the uterine mucosa flowing into it at many points. In their book, Kelly and Cullen [

44] describe cases of adenomyoma as “diffuse gland containing myomatous thickening” either confined to the anterior, posterior, or lateral uterine muscle wall or totally encircling the uterus. Normal uterine mucosa was observed to flow within the myomatous tissue, either as isolated glands or as large masses of mucosa. The mucosa lining the uterine cavity was normal. These descriptions are more aligned with our current understanding of uterine adenomyosis, with less emphasis on large tumour masses.

In contrast to the infrequent cases reported in the 19th century, Cullen [

14] wrote that he was “amazed at the widespread distribution of these tumors”. He classified these lesions based on their site: the body of the uterus, the rectovaginal septum, the uterine horn or the Fallopian tube, the round ligament, the uterosacral ligament, the sigmoid flexure, the rectus muscle and the umbilicus. There is a similarity here with the classification provided in Lockyer’s text, which Cullen had received. Cullen’s description of the lesions is also aligned with our current understanding and includes striations, with scattered chocolate-coloured areas, varying in diameter from 1–5 mm and histologically scattered endometrial glands accompanied by stroma.

4. The Search for the Origin of Mucosal Invasions

Several theories were advances about the aetiology of these lesions. In the main, the mucosa was considered to arise from ‘invasion’ from uterine mucosa, ‘implantation’ of uterine epithelium from retrograde menstruation or following ‘hematogenous’ or ‘lymphatic’ spread, or to originate from ‘embryonic remnants’ (either duplicate, rudimentary or cellular structures). Theories were advanced based on plausibility or histological continuity, or lesion morphology. Many authors were willing to entertain the possibility that diseases at various sites have different aetiologies; others sought a unified theory. Only occasionally did these early researchers undertake a diligent search for tissue continuity, or for experimental studies. Early literature reflects curiosity about the origin of the observed cystic structures and, when recognised, of the mucosal component.

As well as stating their preferred theory, many writers included a critique of alternatives. Von Recklinghausen [28] included histological sections depicting mucosal invasion forming adenomyomas which he classified based on their location at the periphery of the uterus and in the tubes, or centrally within the uterus. He stated that he was unable to find convincing evidence of dissimilarities from the uterine epithelium. Nevertheless, he concluded that whilst it is possible to envisage that lesions close to the uterine cavity originate from endometrial glands, he remained unconvinced that the same origin could apply to lesions closer to the peritoneum. His studies of the shape and branching of the glands led him to the hypothesis that peripheral lesions are derived from Wolffian remnants and that the surrounding stroma is derived from differentiation of local connective tissue. There were many opponents to the Wolffian theory, including Kossmann [45] who argued that aberrant glands originate from accessory Müllerian, rather than Wolffian ducts. Ivanoff [32] proposed that lesions in the peritoneum that do not have a connection to the uterine mucosa arise through metaplasia. This view was supported by Meyer [46] and by more recent authors as the origin of endometriosis [47]. Meyer [46] believed that aberrant glands develop in response to a sequence of inflammation, induration and epithelial hypertrophy. According to this theory, the source of the epithelium is the overlying peritoneum and the surrounding mantle originates from original connective tissue exhibiting response to inflammation.

Cullen [14] took the position that, for the majority of cases, the glands were derived from the uterine mucosa. Von Franqué [48] believed that epithelial growths found in a number of abdominal organs were derived from the ‘mature mucous membrane’ of the uterus that had acquired the ability to infiltrate other organs as a consequence of a process of inflammation. Other early supporters of Cullen’s theory were Baldy and Longcope [49], who refused both von Recklinghausen’s [28] Wolffian hypothesis and Kossmann’s theory [45] of an origin from accessory Müllerian ducts. Schickele [50] was amongst the last to argue in favour of a mesonephric origin of mucosal growth. He wrote, “when I try to take an impartial view of published cases, I am compelled to state that the mucosal theory is not proved”.

In connection with lesions of the rectogenital space, Lockyer [24] described Cullen as being dogmatic in stating that “glands in these growths undoubtedly arise from the uterine mucosa, or from remnants of Muller’s duct”. To Cullen, the presence of a connection between glands within the muscle and the mucosa was sufficient for him to assert that glandular elements of diffuse adenomyoma have undoubtedly arisen from uterine glands [33]. Lockyer drew a distinction, not addressed by Cullen in his assertions, between an origin from ‘dystopic’ (congenital) or ‘orthotopic’ (mature) mucosa and pointed out that it had not been proven that mature uterine mucosa provided any gland-tissue to any etrauterine growth. There are also references stating that the glands derive from the Gartner duct (‘ductus longitudinalis epoophori’), discovered and described in 1822 by Hermann Treschow Gartner as part of the Wolffian duct [51].

Many theories were proposed by the end of the XIX century to explain the origin of ovarian lesions, including a derivation from the germinal epithelium as supported by Waldeyer [52], Marchand [53] and Williams [54] or from the Graafian follicle as supported by Frommel [55] and Williams [54].

In addition to deliberations about pathogenesis, early literature debated nomenclature. Many researchers were not satisfied with the various proposed terms, including those that they themselves had initially supported. A critical factor was the desire to introduce nomenclature that did not imply mechanism or causation. For example, the term Müllerianosis as advocated by Bailey [56] was described by Sampson [57] as inclusive and correct; however, he preferred the term endometriosis to avoid a suggestion of an embryonic origin. It is notable that Sampson also rejected the terms endometrioma or endometriomyoma proposed by Blair Bell [58].