Essential oils (EOs) is new possible weapons to fight antimicrobial resistance due to their inherent antimicrobial properties. However, the potential pharmaceutical use of EOs is confronted by several limitations, including being non-specific in terms of drug targeting, possessing a high cytotoxicity as well as posing a high risk for causing skin irritation.

- essential oils

- antimicrobial

- cell membrane

- membrane permeability

- biopesticides

- encapsulation

- polymeric nanoparticle

1. Introduction

Essential oils (EOs) are highly concentrated and complex mixtures of chemical components produced by aromatic plants in the form of secondary metabolites. EOs are usually obtained by various extraction methods, such as steam distillation, hydro-distillation and supercritical carbon dioxide [1]. EO components are typically volatile and hydrophobic; these attributes are representative of the unique physiochemical properties for a particular EO as a key marker of the oil quality and its characteristics. Various in vitro and in vivo studies have documented the biological benefits of EOs and their active compounds, such as possessing antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-tumour and anti-inflammatory properties [2][3]. In addition to the rapid emergence of the antibiotic resistance crisis worldwide, there is a clear urgency for the development of new antimicrobial compounds; EOs have also been favourably viewed in this regard due to their promising antimicrobial properties and therapeutic potential [4][5]. The mechanisms of action of the EOs and/or their components against bacteria have also been widely explored. O’Bryan et al. (2015) [6] compiled a wealth of information on various antibacterial targets of EOs against the bacterial cell; these included the bacterial cell wall or membrane [7], cellular respiration processes [8][9] and quorum sensing mechanisms [10][11].

Some compounds in EOs have been observed to be toxic to the cells. In fact, among the major problems encountered in the pharmaceutical applications of EOs is their toxicity to mammalian cells, despite this occurrence being documented relatively poorly. Evidence has shown that the lipophilic character of EO compounds and interactions with hydrophobic parts of the cell play a crucial role in the mechanism of toxicity. Thus, experimental data on the toxic effects of the lipophilic EOs on microorganisms in general will be valuable in postulating a general toxicity pathway on other biological membranes in the system.

2. Membrane Disruption Activities of EOs

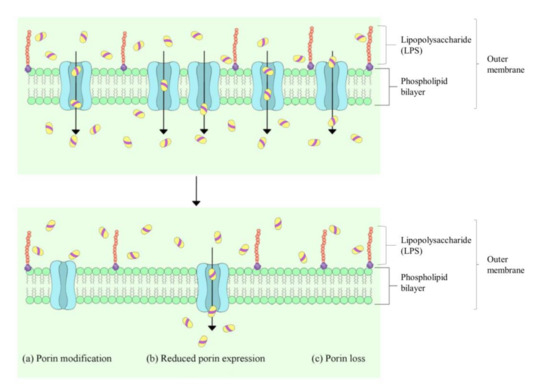

While diverse antimicrobial mechanisms have been described, the bacterial cell wall and membrane have frequently been reported to be the first target of EOs [7][10][12][13]. Toxic effects on membrane integrity and function are generally used to explain the antibacterial activity of EOs, as attributed by the hydrophobic nature of EOs [6]. Studies have indicated that the mechanism of action of the EOs is not isolated but connected to a series of events that involve both external envelopes of the cell and the cytoplasm [12]. Both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria possess peptidoglycans in their cell wall, which are essential for maintaining the cell shape and providing structural integrity. The bacterial plasma membrane is composed of a phospholipid bilayer and plays a general role in cellular function as a permeability barrier for molecules in and out of the cell. Unlike the Gram-positive bacteria, the Gram-negative bacteria possess a lipid-rich outer membrane and thin peptidoglycan. Among the major components of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria is the lipopolysaccharide (LPS); the assembly of these lipids and porins forms a selective barrier to protect the bacteria from several antibiotics, detergents and dyes that would otherwise damage the inner membrane. Various studies have demonstrated that the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria is an effective and evolving antibiotic barrier [14][15] (Figure 1), which makes the outer membrane-targeting antibiotic, colistin, inevitably the treatment of last resort in response to infections caused by extensively multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens. EOs, however, provide a promising alternative as they are not only limited to a certain class of bacteria, but they have also been shown to have potent effects on both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

Figure 1. Generalised mechanisms for reduced porin-mediated outer membrane permeability in Gram-negative bacteria. Adapted from Yang et al. (2018) [16].

Quantitative indicators of increased membrane permeability leading to the ultimate loss of cell viability include measurements of potassium leakage [8][17], protein leakage [13], leakage of genetic materials (DNA and RNA) [13][18] and membrane potential [7][10]. High phenolic contents of EOs, such as the presence of carvacrol, eugenol and thymol, were found to be the major drivers for the disruption of the cytoplasmic membrane [19], leading to the passive flux of protons and other ions [20]. Origanum compactum EO was found to exert an effect on the membrane integrity of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, through the quantification of RNA, DNA and protein released from the cytoplasm [13]. In another study, although finger citron (Citrus medica L. var. sarcodactylis) EO generally showed a better bactericidal effect on Gram-positive bacteria than Gram-negative, a similar trend of cell permeability disruption was observed for these two bacteria [21]. This is intriguing because Gram-negative bacteria were reported to be generally more resistant to EOs and other hydrophobic antibiotics compared to Gram-positive bacteria [12][22]. Membrane potential refers to the extracellular and intracellular potential difference of the bacteria, and it plays a crucial role in bacterial metabolism. The decrease in membrane potential may be attributed to the structural damage of the cell membrane [23]. Measuring the bacterial membrane potential can be achieved by determining the ratio between fluorescence dye intensities inside and outside the cell [23][24]. The membrane potential-sensitive dye, 3,3′-dipropylthiacarbocyanide iodide (DiSC35) [25][26][27] and bis-oxonol [9] are commonly used to stain the depolarised bacterial cells after exposure to EOs. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that altered membrane depolarisation may not always lead to cell death, but rather, it can be conditional on the degree of alteration or whether the functionality of the cell was affected. For instance, thymol was found to be able to induce membrane alteration through integration with polar head-groups of the lipid bilayer; however, at low concentrations, the adapted membrane lipid compositions can still regulate and maintain membrane fluidity and function [12][28]. A previous study has suggested that the alteration of zeta potential could be correlated to increased membrane permeability and eventually be linked to decreased cell viability [29]. Other studies have also reported on an altered zeta potential in Escherichia coli after exposure to lavender EO [10], cinnamon bark EO [11], citronellal, carveol and carvone [30]; these have been substantiated by other membrane disruption tests, including potassium leakage assay and SEM observation. Additionally, Yang et al. [7] reported reduced zeta potential on carbapenemase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae after treatment with lavender EO alone and lavender EO in combination with meropenem. Zeta potential measurement showed that lavender EO increased the overall surface charge of the bacterial cells, which is associated to the loss of LPS [7].

EOs contain many highly conjugated cyclic hydrocarbons, such as aromatic rings and terpenes; these structures are toxic to microorganisms [6][31]. The accumulation of hydrocarbon molecules results in the swelling of the membrane bilayer, leading to cellular content leakage as a direct effect [20], and can also be qualitatively assessed by electron microscopy. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) enables the observation on the ultrastructure of the microorganism, while transmission electron microscopy (TEM) reveals the plasma membranous structures of a cell. Burt and Reinders (2003) demonstrated morphological alterations and loss of contents of Escherichia coli O157:H7 cells by SEM observation following the treatment of oregano EO, which is rich in carvacrol and thymol [32]. Tyagi and Malik (2012) studied the morphological and ultrastructural alterations of lemon grass oil and its vapour against E. coli and showed that the oil-treated cells appeared aggregated, shrunken and partially deformed under SEM observation, whereas TEM photomicrographs revealed uneven cell wall thickness as compared to the control [33]. Lemon grass vapour-treated cells showed the most extensive internal damage and abnormalities compared to lemon grass in liquid phase under TEM inspection. Subsequent atomic force microscopy (AFM) analysis confirmed that the effect of volatile phase of this EO on the bacterial cell wall and/or membrane was more prominent than its liquid phase [33]. Such an observation could be attributed to a more efficient partition into membrane structures of bacteria in the gaseous phase, thereby requiring lower effective bactericidal concentrations to minimise the effects on organoleptic properties [34]. Di Pasqua et al. (2007) evaluated the structure and lipid profile alterations of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria after exposure to various EO constituents by fatty acid analysis and SEM examination [35]. Although the study showed varying levels of membrane disruption of tested compounds on different bacteria, the mechanism of action indicates a direct interference on the membrane lipid biosynthesis pathway [35]. Similar ultrastructural alterations were also observed through the accumulation and increase in electron density of lipid droplets in EO-treated parasitic cells via TEM [36][37].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/pr9040595

References

- Tongnuanchan, P.; Benjakul, S. Essential oils: Extraction, bioactivities, and their uses for food preservation. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, R1231–R1249.

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Sureda, A.; Tenore, G.C.; Daglia, M.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Valussi, M.; Tundis, R.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Loizzo, M.R.; Ademiluyi, A.O.; et al. Biological Activities of Essential Oils: From Plant Chemoecology to Traditional Healing Systems. Molecules 2017, 22, 70.

- Mancianti, F.; Ebani, V.V. Biological Activity of Essential Oils. Molecules 2020, 25, 678.

- Yap, P.S.; Yiap, B.C.; Ping, H.C.; Lim, S.H. Essential oils, a new horizon in combating bacterial antibiotic resistance. Open Microbiol. J. 2014, 8, 6–14.

- Feyaerts, A.F.; Luyten, W.; Van Dijck, P. Striking essential oil: Tapping into a largely unexplored source for drug discovery. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2867.

- O’Bryan, C.A.; Pendleton, S.J.; Crandall, P.G.; Ricke, S.C. Potential of Plant Essential Oils and Their Components in Animal Agriculture—In vitro Studies on Antibacterial Mode of Action. Front. Vet. Sci. 2015, 2, 35.

- Yang, S.K.; Yusoff, K.; Thomas, W.; Akseer, R.; Alhosani, M.S.; Abushelaibi, A.; Lim, S.H.; Lai, K.S. Lavender essential oil induces oxidative stress which modifies the bacterial membrane permeability of carbapenemase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 819.

- Cox, S.D.; Mann, C.M.; Markham, J.L.; Bell, H.C.; Gustafson, J.E.; Warmington, J.R.; Wyllie, S.G. The mode of antimicrobial action of the essential oil of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree oil). J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 88, 170–175.

- Bouhdid, S.; Abrini, J.; Amensour, M.; Zhiri, A.; Espuny, M.J.; Manresa, A. Functional and ultrastructural changes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus cells induced by Cinnamomum verum essential oil. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 109, 1139–1149.

- Yap, P.S.; Krishnan, T.; Yiap, B.C.; Hu, C.P.; Chan, K.G.; Lim, S.H. Membrane disruption and anti-quorum sensing effects of synergistic interaction between Lavandula angustifolia (lavender oil) in combination with antibiotic against plasmid-conferred multi-drug-resistant Escherichia coli. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 116, 1119–1128.

- Yap, P.S.; Krishnan, T.; Chan, K.G.; Lim, S.H. Antibacterial Mode of Action of Cinnamomum verum Bark Essential Oil, Alone and in Combination with Piperacillin, Against a Multi-Drug-Resistant Escherichia coli Strain. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 1299–1306.

- Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; De Martino, L.; Coppola, R.; De Feo, V. Effect of essential oils on pathogenic bacteria. Pharmaceuticals 2013, 6, 1451–1474.

- Bouyahya, A.; Abrini, J.; Dakka, N.; Bakri, Y. Essential oils of Origanum compactum increase membrane permeability, disturb cell membrane integrity, and suppress quorum-sensing phenotype in bacteria. J. Pharm. Anal. 2019, 9, 301–311.

- May, K.L.; Grabowicz, M. The bacterial outer membrane is an evolving antibiotic barrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8852–8854.

- Powers, M.J.; Trent, M.S. Phospholipid retention in the absence of asymmetry strengthens the outer membrane permeability barrier to last-resort antibiotics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E8518–E8527.

- Yang, S.K.; Low, L.Y.; Yap, P.S.X.; Yusoff, K.; Mai, C.W.; Lai, K.S.; Lim, S.H.E. Plant-Derived Antimicrobials: Insights into Mitigation of Antimicrobial Resistance. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2018, 12, 295–316.

- Cox, S.D.; Gustafson, J.E.; Mann, C.M.; Markham, J.L.; Liew, Y.C.; Hartland, R.P.; Bell, H.C.; Warmington, J.R.; Wyllie, S.G. Tea tree oil causes K+ leakage and inhibits respiration in Escherichia coli. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1998, 26, 355–358.

- Tang, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, S.; Ye, S.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, D. Exploring the antibacterial mechanism of essential oils by membrane permeability, apoptosis and biofilm formation combination with proteomics analysis against methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 310, 151435.

- Pauli, A. Antimicrobial properties of essential oil constituents. Int. J. Aromather. 2001, 11, 126–133.

- Sikkema, J.; de Bont, J.A.; Poolman, B. Interactions of cyclic hydrocarbons with biological membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 8022–8028.

- Li, Z.H.; Cai, M.; Liu, Y.S.; Sun, P.L.; Luo, S.L. Antibacterial Activity and Mechanisms of Essential Oil from Citrus medica L. var. sarcodactylis. Molecules 2019, 24, 577.

- Nikaido, H. Porins and specific diffusion channels in bacterial outer membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 3905–3908.

- Novo, D.; Perlmutter, N.G.; Hunt, R.H.; Shapiro, H.M. Accurate flow cytometric membrane potential measurement in bacteria using diethyloxacarbocyanine and a ratiometric technique. Cytometry 1999, 35, 55–63.

- Wang, X.; Shen, Y.; Thakur, K.; Han, J.; Zhang, J.G.; Hu, F.; Wei, Z.J. Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of Ginger Essential Oil against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Molecules 2020, 25, 3955.

- Veldhuizen, E.J.; Tjeerdsma-van Bokhoven, J.L.; Zweijtzer, C.; Burt, S.A.; Haagsman, H.P. Structural requirements for the antimicrobial activity of carvacrol. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 1874–1879.

- Ultee, A.; Bennik, M.H.; Moezelaar, R. The phenolic hydroxyl group of carvacrol is essential for action against the food-borne pathogen Bacillus cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 1561–1568.

- Topa, S.H.; Subramoni, S.; Palombo, E.A.; Kingshott, P.; Rice, S.A.; Blackall, L.L. Cinnamaldehyde disrupts biofilm formation and swarming motility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 2018, 164, 1087–1097.

- Turina, A.V.; Nolan, M.V.; Zygadlo, J.A.; Perillo, M.A. Natural terpenes: Self-assembly and membrane partitioning. Biophys. Chem. 2006, 122, 101–113.

- Halder, S.; Yadav, K.K.; Sarkar, R.; Mukherjee, S.; Saha, P.; Haldar, S.; Karmakar, S.; Sen, T. Alteration of Zeta potential and membrane permeability in bacteria: A study with cationic agents. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 672.

- Lopez-Romero, J.C.; González-Ríos, H.; Borges, A.; Simões, M. Antibacterial Effects and Mode of Action of Selected Essential Oils Components against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 795435.

- Sikkema, J.; de Bont, J.A.; Poolman, B. Mechanisms of membrane toxicity of hydrocarbons. Microbiol. Rev. 1995, 59, 201–222.

- Burt, S.A.; Reinders, R.D. Antibacterial activity of selected plant essential oils against Escherichia coli O157:H7. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 36, 162–167.

- Tyagi, A.K.; Malik, A. Morphostructural Damage in Food-Spoiling Bacteria due to the Lemon Grass Oil and Its Vapour: SEM, TEM, and AFM Investigations. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 692625.

- Inouye, S.; Nishiyama, Y.; Uchida, K.; Hasumi, Y.; Yamaguchi, H.; Abe, S. The vapor activity of oregano, perilla, tea tree, lavender, clove, and geranium oils against a Trichophyton mentagrophytes in a closed box. J. Infect. Chemother. 2006, 12, 349–354.

- Di Pasqua, R.; Betts, G.; Hoskins, N.; Edwards, M.; Ercolini, D.; Mauriello, G. Membrane toxicity of antimicrobial compounds from essential oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 4863–4870.

- Rottini, M.M.; Amaral, A.C.F.; Ferreira, J.L.P.; Oliveira, E.S.C.; Silva, J.R.A.; Taniwaki, N.N.; Dos Santos, A.R.; Almeida-Souza, F.; de Souza, C.; Calabrese, K.D.S. Endlicheria bracteolata (Meisn.) Essential Oil as a Weapon Against Leishmania amazonensis: In Vitro Assay. Molecules 2019, 24, 2525.

- Oliveira, V.C.; Moura, D.M.; Lopes, J.A.; de Andrade, P.P.; da Silva, N.H.; Figueiredo, R.C. Effects of essential oils from Cymbopogon citratus (DC) Stapf., Lippia sidoides Cham., and Ocimum gratissimum L. on growth and ultrastructure of Leishmania chagasi promastigotes. Parasitol. Res. 2009, 104, 1053–1059.