Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancy and cause of cancer death worldwide, and it still remains a therapeutic challenge for western medicine. There is strong evidence that, in addition to genetic predispositions, environmental factors have also a substantial impact in CRC development. The risk of CRC is attributed, among others to dietary habits, alcohol consumption, whereas physical activity, food containing dietary fiber, dairy products, and calcium supplements have a protective effect. Despite progress in the available therapies, surgery remains a basic treatment option for CRC. Implementation of additional methods of treatment such as chemo- and/or targeted immunotherapy, improved survival rates, however, the results are still far from satisfactory.

- granulocytes

- colorectal cancer

- myeloid derived suppressor cells

- eosinophils

- basophils

- neutrophils

- tumor associated neutrophils

1. CRC

CRC is the third most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. The latest data showed also a shift in the mean age of CRC onset from 72 to 66 years of age [2]. Despite the fact that the overall mortality caused by CRC is continuously declining, the survival and quality of life (QOL) remains poor, especially in an advanced stage of disease [3]. Surgery is still a basic treatment option, in particular for early tumor stage, while for more advanced tumors, effective chemotherapy regimens brought improved survival rates, which was additionally enhanced recently by the introduction of monoclonal antibody-based targeted immunotherapy [4]. Currently, tumor histological status and TNM (tumor, nodes, and metastases) staging during diagnosis remains a basic prognostic marker for CRC [5]. Thus, the development of additional systems that can effectively predict the disease’s progression and efficacy of the therapy in individual patients is highly desirable [6]. Age, genetic predispositions and environmental factors, including diet habits—especially red meat consumption, alcohol abuse, and lack of physical activity, among others, play a major role in CRC development. There are also reports documenting association of CRC with obesity, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and immunosuppression in organ transplant patients [7], all emphasizing a crucial role of the immune system in CRC development. Although, CRC has long been considered as not typically immunogenic, multiple studies have shown that T lymphocyte component of the tumor mass is relevant and may have a prognostic value for CRC patients [8]. For example, in patients with curatively resected CRC, the tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in the invasive margin and CD8+ T cell in the central part of the tumor were detected, demonstrating an active anti-tumor immune response [9]. However, not all of the T cells in the tumor environment are considered to be beneficial—e.g., regulatory T cells (Treg) have a potent pro-tumorigenic activity [10][11]. Recent data provide new prognostic/predictive modes based on the numbers of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and Treg, being more reliable than traditional indicators for evaluating CRC patients [12]. In this context, the role of granulocytes and their subsets has not been fully recognized. In this review we present the role and mechanisms of action of granulocytes and cells of granulocyte origin, specifically Gr-MDSCs, as possible prognostic factors or therapy targets in CRC.

2. Therapies Targeting Neutrophils in CRC

In this context, there are several clinical trials ongoing using the drugs that can affect neutrophil and TAN functions—e.g., phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor (NCT02544880), neutrophil elastase inhibitor (NCT01170845), COX2 inhibitor, NCT00752115), and arginase inhibitor (NCT02903914). However, only the last one refers to CRC. Another clinical study refers to aspirin and its protective effect on the development of CRC (NCT02394769). A growing awareness of the neutrophil role in CRC may be further demonstrated by clinical trial focused on evaluation of the postoperative glutamine-dipeptide and/or omega 3 fatty acids supplementation on their activity (NCT01831310). Furthermore, blocking TGFβ involved in the induction of neutrophils with protumor phenotype, was suggested as a potential therapeutic strategy. Indeed, Fridlender et al. showed that blocking of TGFβ increased recruitment of anti-tumor pro-inflammatory neutrophils in mice [13]. Unfortunately, the clinical trials based on this approach failed due to significant side effects as TGFβ is involved in a number of physiological pathways [14]. Another approach is based on the blocking of TGFβ receptor II (IMC-TR1/LY3022859) and despite the promising results in mouse models of CRC and breast cancer [15], it was shown to be ineffective in the later clinical trials [16]. Now LY2157299 and LY3200882 which are the TGFβ receptor type I inhibitors are studied in the advanced CRC (NCT03470350, NCT04031872).

Due to the importance of IL-8 secreted by CRC cells in the recruitment of neutrophils, a good therapeutic approach seems to be blocking the CXCL8 (IL-8) axis [17][18]. Consequently, BMS-986253—an anti-IL-8 antibody, is being tested in clinical trial in combination with Nivolumab (anti-PD-1) in patients with advanced solid tumors, including CRC (NCT03400332). Similarly, blocking granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in cancer patients with neutrophilia is also attractive. Both G-CSF and GM-CSF are used in neutropenia related to cancer treatment (NCT04166604, NCT03102606, NCT00002950); however, as was shown in mouse models, both may induce granulocytes with immunosuppressive functions [19][20]. Additionally, both contribute to acquisition by neutrophils pro-metastatic properties [21][22]. However, to optimize the efficacy of anti-tumor immunotherapy a better understanding of neutrophil-related mechanisms in tumor immunity is essential.

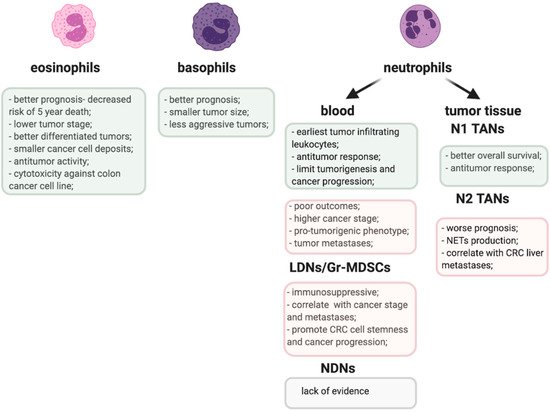

The proposed role of TANs and other granulocyte populations in CRC is emphasized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Pro-(pink) and anti-tumorigenic (greenish) activities of granulocyte populations in CRC.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22073801

References

- Keum, N.N.; Giovannucci, E. Global Burden of Colorectal Cancer: Emerging Trends, Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 713–732.

- Charles, J.; Kahi, M.M. Colorectal Cancer 2020 Epidemiological Update. NEJM J. Watch 2020.

- Cronin, K.A.; Lake, A.J.; Scott, S.; Sherman, R.L.; Noone, A.M.; Howlader, N.; Henley, S.J.; Anderson, R.N.; Firth, A.U.; Ma, J.; et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, Part I: National Cancer Statistics. Cancer 2018, 124, 2785–2800.

- Saltz, L.B.; Cox, J.V.; Blanke, C.; Rosen, L.S.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Moore, M.J.; Maroun, J.A.; Ackland, S.P.; Locker, P.K.; Pirotta, N.; et al. Irinotecan plus Fluorouracil and Leucovorin for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 905–914.

- Bosch, L.J.W.; Carvalho, B.; Fijneman, R.J.A.; Jimenez, C.R.; Pinedo, H.M.; van Engeland, M.; Meijer, G.A. Molecular Tests for Colorectal Cancer Screening. Clin. Colorect. Cancer 2011, 10, 8–23.

- Anitei, M.G.; Zeitoun, G.; Mlecnik, B.; Marliot, F.; Haicheur, N.; Todosi, A.M.; Kirilovsky, A.; Lagorce, C.; Bindea, G.; Ferariu, D.; et al. Prognostic and Predictive Values of the Immunoscore in Patients with Rectal Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 1891–1899.

- Thanikachalam, K.; Khan, G. Colorectal Cancer and Nutrition. Nutrients 2019, 11, 164.

- Ogino, S.; Nosho, K.; Irahara, N.; Meyerhardt, J.A.; Baba, Y.; Shima, K.; Glickman, J.N.; Ferrone, C.R.; Mino-Kenudson, M.; Tanaka, N.; et al. Lymphocytic Reaction to Colorectal Cancer Is Associated with Longer Survival, Independent of Lymph Node Count, Microsatellite Instability, and CpG Island Methylator Phenotype. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 6412–6420.

- Chan, L.F.; Sadahiro, S.; Suzuki, T.; Okada, K.; Miyakita, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Kajiwara, H. Tissue-Infiltrating Lymphocytes as a Predictive Factor for Recurrence in Patients with Curatively Resected Colon Cancer: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Oncology 2020, 98, 680–688.

- Li, C.; Jiang, P.; Wei, S.; Xu, X.; Wang, J. Regulatory T Cells in Tumor Microenvironment: New Mechanisms, Potential Therapeutic Strategies and Future Prospects. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 116.

- Park, Y.J.; Ryu, H.; Choi, G.; Kim, B.S.; Hwang, E.S.; Kim, H.S.; Chung, Y. IL-27 Confers a Protumorigenic Activity of Regulatory T Cells via CD39. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 3106–3111.

- Ye, L.; Zhang, T.; Kang, Z.; Guo, G.; Sun, Y.; Lin, K.; Huang, Q.; Shi, X.; Ni, Z.; Ding, N.; et al. Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells Act as a Marker for Prognosis in Colorectal Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2368.

- Fridlender, Z.G.; Sun, J.; Kim, S.; Kapoor, V.; Cheng, G.; Ling, L.; Worthen, G.S.; Albelda, S.M. Polarization of Tumor-Associated Neutrophil Phenotype by TGF-β: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell 2009, 16, 183–194.

- Bierie, B.; Moses, H.L. Tumour Microenvironment—TGFΒ: The Molecular Jekyll and Hyde of Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 506–520.

- Zhong, Z.; Carroll, K.D.; Policarpio, D.; Osborn, C.; Gregory, M.; Bassi, R.; Jimenez, X.; Prewett, M.; Liebisch, G.; Persaud, K.; et al. Anti-Transforming Growth Factor β Receptor II Antibody Has Therapeutic Efficacy against Primary Tumor Growth and Metastasis through Multieffects on Cancer, Stroma, and Immune Cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 1191–1205.

- Tolcher, A.W.; Berlin, J.D.; Cosaert, J.; Kauh, J.; Chan, E.; Piha-Paul, S.A.; Amaya, A.; Tang, S.; Driscoll, K.; Kimbung, R.; et al. A Phase 1 Study of Anti-TGFβ Receptor Type-II Monoclonal Antibody LY3022859 in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2017, 79, 673–680.

- Kumar, A.; Cherukumilli, M.; Mahmoudpour, S.H.; Brand, K.; Bandapalli, O.R. ShRNA-Mediated Knock-down of CXCL8 Inhibits Tumor Growth in Colorectal Liver Metastasis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 500, 731–737.

- Mizukami, Y.; Jo, W.-S.; Duerr, E.-M.; Gala, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Zimmer, M.A.; Iliopoulos, O.; Zukerberg, L.R.; Kohgo, Y.; et al. Induction of Interleukin-8 Preserves the Angiogenic Response in HIF-1α–Deficient Colon Cancer Cells. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 992–997.

- Casbon, A.J.; Reynau, D.; Park, C.; Khu, E.; Gan, D.D.; Schepers, K.; Passegué, E.; Werb, Z. Invasive Breast Cancer Reprograms Early Myeloid Differentiation in the Bone Marrow to Generate Immunosuppressive Neutrophils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E566–E575.

- Bayne, L.J.; Beatty, G.L.; Jhala, N.; Clark, C.E.; Rhim, A.D.; Stanger, B.Z.; Vonderheide, R.H. Tumor-Derived Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor Regulates Myeloid Inflammation and T Cell Immunity in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 822–835.

- Qu, X.; Zhuang, G.; Yu, L.; Meng, G.; Ferrara, N. Induction of Bv8 Expression by Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor in CD11b+Gr1+ Cells: Key Role of Stat3 Signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 19574–19584.

- Queen, M.M.; Ryan, R.E.; Holzer, R.G.; Keller-Peck, C.R.; Jorcyk, C.L. Breast Cancer Cells Stimulate Neutrophils to Produce Oncostatin M: Potential Implications for Tumor Progression. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 8896–8904.