First-line immune-checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)-based therapy has deeply changed the treatment landscape and prognosis in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (aNSCLC) patients with no targetable alterations. Nonetheless, a percentage of patients progressed on ICI as monotherapy or combinations. Open questions remain on patients’ selection, the identification of biomarkers of primary resistance to immunotherapy and the treatment strategies to overcome secondary resistance to first-line immunotherapy. Local ablative approaches are the main therapeutic strategies in oligoprogressive disease, and their role is emerging in patients treated with immunotherapy. Many therapeutic strategies can be adapted in aNSCLC patients with systemic progression to personalize the treatment approach according to re-characterization of the tumors, previous ICI response, and type of progression.

- non-small cell lung cancer

- oligoprogression

- immune checkpoint inhibitor

- immunotherapy

- local therapy

- resistance

1. Introduction

In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have dramatically changed the treatment landscape of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (aNSCLC). Most aNSCLC patients do not harbor a targetable alteration (non-oncogene aNSCLC); thus, immunotherapy, as single agent or in combination with other drugs (immuno-chemotherapy (CT)—ICI-CT—or immuno-immunotherapy—ICI-ICI) are the mainstay treatment based on the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)’s expression [1][2].

Despite the survival advantage, only a percentage of aNSCLC patients respond to single-agent ICI (20–30%) and ICI-based combinations (50–60%), while most patients experience disease progression [1][2]. The treatment choice after failure of first-line ICI-based therapy depends on previous treatment, type of response and progression, the burden of disease, and patient performance. Several unanswered questions include patients’ selection and the identification of prognostic and predictive biomarkers of primary and secondary resistance to ICIs. The establishment of therapeutic strategies to overcome failure of ICIsand to extend its benefit in non-responding and progressing patients is a clinical unmet need and a critical area of research [3][4].

2. Treatment Option Strategies for Early Systemic Progression and Late Systemic Progression

2.1. Treatment Option Strategies for Early Systemic Progression

We reported different strategies for overcoming resistance that leads to ES-PD and IS-PD including (1) strategies with immunotherapy, (2) strategies beyond immunotherapy, and (3) innovative trials with different multiple approaches.

2.1.1. Strategies with Immunotherapy

The therapeutic strategies with the use of immunotherapy beyond progression included the use of (1) second-generation immunotherapeutic agents, (2) the combination of immunotherapy with antiangiogenic agents, and (3) the combination of immunotherapeutic agents.

2.1.2. Strategies beyond Immunotherapy

The therapeutic strategies with the interruption of immunotherapy include the use of (1) CT in combination with antiangiogenetics, (2) CT alone and (3) the use of new TKIs.

2.1.3. Multiple Strategies and Innovative Trials

Different trials are assessing different anticancer therapies in aNSCLC patients pretreated with immunotherapy.

The HUDSON trial is an ongoing phase II umbrella study that enrols aNSCLC patients who progressed after a platinum-based CT and an anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy, as monotherapy or in combinations. Different drugs with different mechanisms of action are assessed in combination with durvalumab including olaparib, AZD9150 (JAK-STAT3 pathway-inhibitor), ceralasertib (ATR kinase inhibitor), vistusertib (mTOR inhibitor), oleclumab (anti-CD73), trastuzumab-deruxtecan (antibody–drug conjugate) and cediranib (anti-VEGFR-1-3) [NCT03334617] [5].

In the phase I/II CheckMate 79X study, aNSCLC patients who progressed on ICIs and CT (given either concurrently or sequentially) are randomized to docetaxel versus different nivolumab-containing combinations including nivolumab (plus ipilimumab) plus cabozantinib, docetaxel plus ramucirumab, docetaxel and lucitanib, which is a VEGFR-1-3 and FGFR-1-2 inhibitor [NCT04151563].

In recent years, the CAR-T cells immunotherapy, consisting in patient’s T cells genetically engineered to produce an artificial T-cell receptor, has reported great results in many malignancies, especially in hematologic ones [6]. In aNSCLC patients, several trials are ongoing evaluating the safety and activity of CAR-T cells in different treatment settings [NCT03525782, NCT02587689].

Other co-inhibitory receptors and cell surface ligands are under investigation including T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 (Tim-3), lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3), and Carcinoembryonic Antigen-related Cell Adhesion Molecule 5 (CEACAM5).

T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 is a co-inhibitory receptor particularly expressed on exhausted CD8+ T cells and in preclinical models the co-block of PD(L)-1 and Tim-3 receptors has shown to be effective in solid tumors [7]. Furthermore, Tim-3 deregulation has been associated with the development of resistance to PD(L)-1 inhibition in NSCLC patients [8]. Many phase I/II studies are investigating the efficacy of Tim-3 antagonists in association with anti-PD(L)-1. Preliminary data of the phase I AMBER study on the combination of TSR-022 (anti-TIM-3 monoclonal antibody), and TSR-042 (anti-PD-1 inhibitor) showed promising clinical activity and good safety in aNSCLC patients progressed on anti-PD(L)-1 treatment (NCT02817633) [7][9].

Another ongoing phase I/II trial evaluates the safety and activity of MBG453 (Tim-3 inhibitor) with or without PDR001 (anti-PD-1, spartalizumab) in patients with advanced solid tumors, including aNSCLC patients, pretreated or not with an anti-PD(L)-1 therapy (NCT02608268). The phase II cohort on aNSCLC patients progressed upon anti–PD-(L)1 therapy receiving MBG453 + PDR001 showed good tolerance but limited efficacy [10].

A bispecific antibody inhibiting both Tim-3 and PD-1 (RO7121661) is currently studied in a phase I study in patients with advanced solid tumors including aNSCLC (NCT03708328).

Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 is expressed on activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, Treg and other immune cells. Similar to CD4, Lag-3 binds MHC class II, but with a higher affinity, with the subsequent reduction of T cell proliferation and lower pro-immune cytokine production [11]. There are many ongoing phase I/II trials evaluating the safety and the activity of LAG-3 inhibitors as monotherapy or in association with anti-PD(L)-1 in many advanced tumors, including aNSCLC pretreated with immunotherapy [NCT 02460224, NCT01968109, NCT02913313]. Furthermore, also for LAG-3, there is an anti-PD-1-LAG-3 bispecific antibody that is currently under evaluation in a phase I trial on patients with advanced solid tumors, including aNSCLC patients previously treated with PD-(L)1 inhibitor (NCT04140500).

CEACAM5 is a surface protein on tumors cells involved in cancer invasion and metastatization [12]. SAR408701 is an antibody-drug conjugate that consists of anti-CEACAM5 antibody conjugated to a cytotoxic agent maytansinoid DM4. The CARMAN-LC03 trial is an ongoing phase III trial on SAR408701 versus docetaxel in pretreated CEACAM5+ aNSCLC patients progressing after CT and ICIs [NCT04154956].

For more advanced immunotherapeutic agents (oncolytic viruses, vaccines, other cellular therapy) we suggest referring to dedicated reviews and make a constant bring up to date on dedicated software (e.g., ClinicalTrials.gov (accessed on 6 February 2021), PubMed).

2.2. Treatment Strategies for Late Systemic Progression

Long-responders to immunotherapy should be divided according to the timing of progression in those who progress after interruption of prior immunotherapy and those who progress during immunotherapy. Patients who progress after a therapeutic interval from immunotherapy in monotherapy or combination may benefit from treatment rechallenge of the interrupted therapy.

2.2.1. Rechallenge of Immunotherapy after Immunotherapy

The rechallenge of ICIs could be defined as a second course of treatment after an interval of almost 3 months. This because, regardless of the dose, the half-life of most anti-PD-(L)1 antibodies ranges between 12 and 20 days and the occupancy of PD-1 molecules on circulating T cells remains for almost 3 months [13]. The ICI rechallenge is a promising treatment approach, especially in advanced melanoma patients [14][15][16].

To date, three prospective clinical trials reported the efficacy and safety of ICIs rechallenge in aNSCLC patients. The CheckMate 153 investigated the survival benefit of a fixed-duration (1 year) vs. continuous treatment of nivolumab as second-line therapy in aNSCLC patients. In the fixed-duration arm, 47 patients progressed during the follow-up period and 39 patients (83%) were retreated with the same therapy [17]. The median duration of nivolumab retreatment was 3.8 months and disease progression on target lesions and new lesions were reported in 35% and 41% of cases, respectively [17].

In the phase II/III KEYNOTE-010 trial on pembrolizumab versus docetaxel in pretreated aNSCLC patients with PD-L1 ≥1%, after 2 years of pembrolizumab 25 (32%) patients progressed and 14 (56%) were rechallenged with a second course of pembrolizumab, reporting partial response and stable disease in 43% and 36% of patients, respectively, with a disease control rate of 79% [18][19].

In addition, in the first-line setting, KEYNOTE-024 trial reported a disease control rate of 70% in untreated patients with PD-L1 ≥50% receiving retreatment with pembrolizumab after the completion of 2 years of pembrolizumab [20].

Rechallenge in real life has been recently published in a national database analysis on 10,452 sNSCLC patients treated with nivolumab. About half of the patients received post-nivolumab therapy lines and among them, 1517 patients (about 30%) received a second course of PD-1 inhibitors, either after a treatment-free interval (resumption group, N = 1127), or after chemotherapy (rechallenge group, N = 390). The mOS was 15.0 and 18.4 months in the resumption and rechallenge group respectively and, regardless of the group, it was longer in patients initially receiving nivolumab for ≥3 months [21].

A phase II clinical trial is assessing rechallenge with pembrolizumab as second or further-line in aNSCLC patients progressing on anti-PDL1 drug. This trial consists of two treatment groups depending on when the progression disease occurred: cohort 1 consists of patients progressing during treatment or <12 weeks after stopping it, then received CT ≥4 cycles and progressed again; cohort 2 consists of patients who stopped treatment and progressed after ≥12 weeks (NCT03526887).

According to these data, in aNSCLC patients experiencing a long-term benefit from ICI, the rechallenge of immunotherapy can be considered as a therapeutic option, especially in case of a lack of valid therapeutic alternatives. However, available literature data are not sufficient to give clear recommendations and more prospective trial are needed.

2.2.2. Rechallenge of Chemotherapy after Immuno-Chemotherapy

Rechallenge with CT may be attempted if the disease has initially responded to it and is recommended in many tumors whenever there are no valid treatment alternatives [22].

Several phase II studies investigated the clinical benefit of platinum-based CT in patients previously treated with it with conflicting results [23][24]. The pooled-analysis conducted by Petrelli et al. [23] on 11 studies showed that rechallenge with platinum-based CT was associated with an interesting tumor response rate of 27% but with no survival advantage compared to conventional second-line agents.

The availability of different effective drugs and the potential cumulative platinum-related hematological (neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia) and non-hematological toxicities (renal damage, ototoxicity, neurological toxicity, etc.) makes the platinum-based CT rechallenge an unusual strategy in clinical practice.

However, retreatment with platinum-based CT could be hypothetically proposed for patients treated with first-line ICI-CT who are still in treatment with immunotherapy and with a long time to progression from the last CT.

A prospective trial should be conducted to definitively address if platinum-based CT rechallenge after ICT-CT could represent an option for relapsed platinum-sensitive patients.

3. Conclusions

Identifying effective treatment strategies for NSCLC patients who have progressed upon single-agent ICI or ICI-based combinations is an unmet clinical need and an important issue of clinical research.

Many ongoing studies are investigating different approaches to overcome the different resistance mechanisms in both oligoprogressive and systemic progressive ICI patients, therefore enrollment in clinical trials is recommended.

New LAT methods and drug combinations could overcome resistances in oligo PD during immunotherapy.

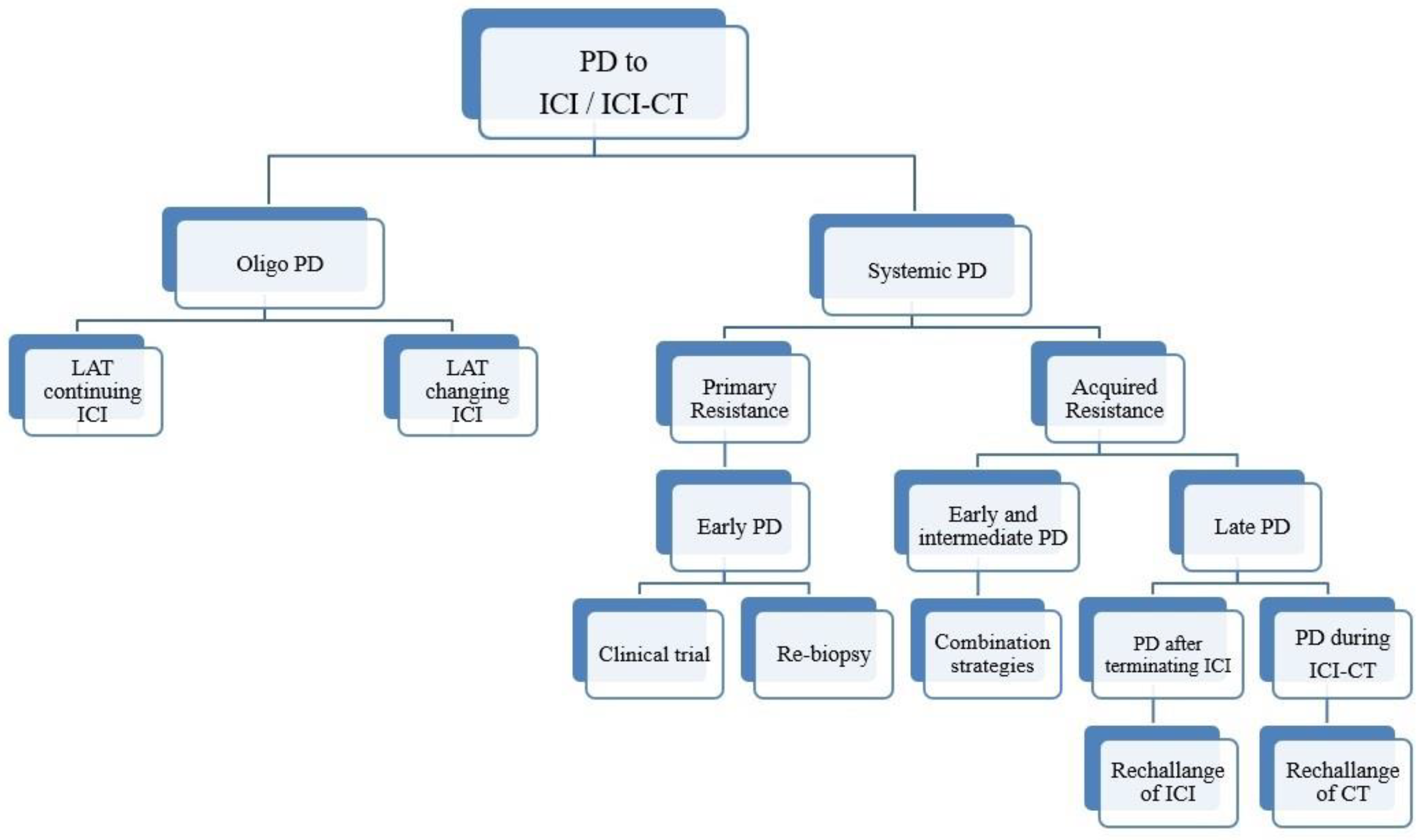

In systemic PD, a new challenge is to estimate the type of resistance by reasoning about the timing of PD and, if possible, by performing a new biopsy (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of an algorithm for patients with NSCLC who progressed upon IO-based therapy.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers13061300

References

- Saxena, P.; Singh, P.K.; Malik, P.S.; Singh, N. Immunotherapy Alone or in Combination with Chemotherapy as First-Line Treatment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2020, 21, 1–21.

- Planchard, D.; Popat, S.; Kerr, K.; Novello, S.; Smit, E.F.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Mok, T.S.; Reck, M.; Van Schil, P.E.; Hellmann, M.D.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines-Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Available online: (accessed on 6 February 2021).

- Heigener, D.F.; Kerr, K.M.; Laing, G.M.; Mok, T.S.; Moiseyenko, F.V.; Reck, M. Redefining Treatment Paradigms in First-line Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 4881–4887.

- Low, J.L.; Walsh, R.J.; Ang, Y.; Chan, G.; Soo, R.A. The evolving immuno-oncology landscape in advanced lung cancer: First-line treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Ther. Adv. Med Oncol. 2019, 11, 1758835919870360.

- Heymach, J.; Thomas, M.; Besse, B.; Forde, P.M.; Awad, M.M.; Goss, G.D.; Park, K.; Rizvi, N.A.; Lao-Sirieix, S.-H.; Patel, S.I.; et al. An open-label, multidrug, biomarker-directed, multicentre phase II umbrella study in patients with non-small cell lung cancer, who progressed on an anti-PD-1/PD-L1 containing therapy (HUDSON). J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, TPS3120.

- Jackson, H.J.; Rafiq, S.; Brentjens, R.J. Driving CAR T-cells forward. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 370–383.

- Acharya, N.; Sabatos-Peyton, C.; Anderson, A.C. Tim-3 finds its place in the cancer immunotherapy landscape. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000911.

- Koyama, S.; Akbay, E.A.; Li, Y.Y.; Herter-Sprie, G.S.; Buczkowski, K.A.; Richards, W.G.; Gandhi, L.; Redig, A.J.; Rodig, S.J.; Asahina, H.; et al. Adaptive resistance to therapeutic PD-1 blockade is associated with upregulation of alternative immune checkpoints. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10501.

- Davar, D.; Boasberg, P.; Eroglu, Z.; Falchook, G.; Gainor, J.; Hamilton, E. A Phase 1 Study of TSR-022, an Anti-TIM-3 Monoclonal Antibody, in Combination with TSR-042 (Anti-PD-1) in Patients with Colorectal Cancer and Post-PD-1 NSCLC and Melanoma. In Proceedings of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer 33rd Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 7–11 November 2018.

- Mach, N.; Curigliano, G.; Santoro, A.; Kim, D.-W.; Tai, D.; Hodi, S.; Wilgenhof, S.; Doi, T.; Longmire, T.; Sun, H.; et al. Phase (Ph) II study of MBG453 + spartalizumab in patients (pts) with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and melanoma pretreated with anti–PD-1/L1 therapy. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, v491–v492.

- Joller, N.; Kuchroo, V.K. Tim-3, Lag-3, and TIGIT. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2017, 410, 127–156.

- Blumenthal, R.D.; Leon, E.; Hansen, H.J.; Goldenberg, D.M. Expression patterns of CEACAM5 and CEACAM6 in primary and metastatic cancers. BMC Cancer 2007, 7, 2.

- Brahmer, J.R.; Drake, C.G.; Wollner, I.; Powderly, J.D.; Picus, J.; Sharfman, W.H.; Stankevich, E.; Pons, A.; Salay, T.M.; McMiller, T.L.; et al. Phase I Study of Single-Agent Anti–Programmed Death-1 (MDX-1106) in Refractory Solid Tumors: Safety, Clinical Activity, Pharmacodynamics, and Immunologic Correlates. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 3167–3175.

- Ribas, A.; Puzanov, I.; Dummer, R.; Schadendorf, D.; Hamid, O.; Robert, C.; Hodi, F.S.; Schachter, J.; Pavlick, A.C.; Lewis, K.D.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for ipilimumab-refractory melanoma (KEYNOTE-002): A randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 908–918.

- Lebbé, C.; Weber, J.S.; Maio, M.; Neyns, B.; Harmankaya, K.; Hamid, O.; O’Day, S.J.; Konto, C.; Cykowski, L.; McHenry, M.B.; et al. Survival follow-up and ipilimumab retreatment of patients with advanced melanoma who received ipilimumab in prior phase II studies. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 2277–2284.

- Larkin, J.; Minor, D.; D’Angelo, S.; Neyns, B.; Smylie, M.; Jr, W.H.M.; Gutzmer, R.; Linette, G.; Chmielowski, B.; Lao, C.D.; et al. Overall Survival in Patients With Advanced Melanoma Who Received Nivolumab Versus Investigator’s Choice Chemotherapy in CheckMate 037: A Randomized, Controlled, Open-Label Phase III Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 383–390.

- Remon, J.; Menis, J.; Aspeslagh, S.; Besse, B. Treatment duration of checkpoint inhibitors for NSCLC. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 835–837.

- Herbst, R.S.; Garon, E.B.; Kim, D.-W.; Cho, B.C.; Perez-Gracia, J.L.; Han, J.-Y.; Arvis, C.D.; Majem, M.; Forster, M.D.; Monnet, I.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes and Retreatment Among Patients With Previously Treated, Programmed Death-Ligand 1‒Positive, Advanced Non‒Small-Cell Lung Cancer in the KEYNOTE-010 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1580–1590.

- Herbst, R.S.; Baas, P.; Kim, D.-W.; Felip, E.; Pérez-Gracia, J.L.; Han, J.-Y.; Molina, J.; Kim, J.-H.; Arvis, C.D.; Ahn, M.-J.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1540–1550.

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez–Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. Updated Analysis of KEYNOTE-024: Pembrolizumab Versus Platinum-Based Chemotherapy for Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score of 50% or Greater. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 537–546.

- Levra, M.G.; Cotté, F.-E.; Corre, R.; Calvet, C.; Gaudin, A.-F.; Penrod, J.R.; Grumberg, V.; Jouaneton, B.; Jolivel, R.; Assié, J.-B.; et al. Immunotherapy rechallenge after nivolumab treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the real-world setting: A national data base analysis. Lung Cancer 2020, 140, 99–106.

- Kuczynski, E.A.; Sargent, D.J.; Grothey, A.; Kerbel, R.S. Drug rechallenge and treatment beyond progression—implications for drug resistance. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 10, 571–587.

- Petrelli, F.; Coinu, A.; Cabiddu, M.; Ghilardi, M.; Ardine, M.; Barni, S. Platinum rechallenge in patients with advanced NSCLC: A pooled analysis. Lung Cancer 2013, 81, 337–342.

- Ardizzoni, A.; Tiseo, M.; Boni, L.; Vincent, A.D.; Passalacqua, R.; Buti, S.; Amoroso, D.; Camerini, A.; Labianca, R.; Genestreti, G.; et al. Pemetrexed Versus Pemetrexed and Carboplatin As Second-Line Chemotherapy in Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Results of the GOIRC 02-2006 Randomized Phase II Study and Pooled Analysis With the NVALT7 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 4501–4507.