Severe skin scars (i.e., hypertrophic and keloid) induce physical and emotional discomfort and functional disorders such as contractures and body part deformations. Scar’s response to treatment depends on “maturity”, which increases with time but is not merely proportional to it. When “fresh”, scars are relatively more treatable by conservative methods, while the treatment is only partially efficient. In contrast, surgery is a preferred approach for the older scars, but it is associated with a risk of the scar regrowth and worsening after excision if unrecognized immature scar tissue remains in the operated lesion. Therefore, to develop better treatment and diagnostics of scars, understanding of the scar maturation is essential. This requires biologically accurate experimental models of skin scarring. The current models only mimic the early stages of skin scar development. They are useful for testing new scar-preventing approaches while not addressing the problem of the older scars that exist for years.

- scarring

- hypertrophic scar

- animal model

- scar maturation

- quantitative histopathology

- collagen

1. Introduction

Hypertrophic scars (HSs) are benign foci of skin fibrosis occurring following traumas, burns and surgical operations and, in contrast to the keloids, remaining within the borders of the original wound [1,2]. These scars are common in clinical practice [3] as they affect 4.5–16% of the population [4]. HSs are elevated above the healthy skin, have reduced elasticity, and may result in the formation of scar contractures. Often, they differ in color from the skin, pruritic or painful. HS may result in disability and social isolation [3].

HSs are dynamic structures. After the wound epithelization, the granulation tissue (and, in special cases such as surgically treated burns, other tissues of the wound bed [5]) transforms into scar tissue [6,7]. This process may take months. Then, the scar tissue undergoes remodeling signifying its adaptation to the local biomechanics and systemic response to the injury. The changes of the external appearance, histological structure and functional activity of the scar reflect the scar maturation. They include growth and consequent decrease of the scar volume and the turgor, color changes (towards more similar to the skin), and sometimes the variations of the intensity of the subjective sensations (itching, pain, etc.) [1,8,9]. According to the literature, the maturation of HS in humans may take from three to six months [10] or up to several years [11]. It is recommended to consider a 6–12 month period as an average time needed for an HS maturation [12].

The morphological substrate of the scar maturation is not fully known [13]. The scar time-course is associated with the reorganization of the extracellular matrix, downregulation of inflammatory reactions, decrease in vascularity and phenotype modification of the fibroblasts, including the fibroblasts-myofibroblasts transitions serving the scar contraction [1,11,13,14,15,16,17,18]. The speed of the maturation of the scar depends on the delay of the epithelization, the intensity of the contraction [18,19,20], as well as the size and the location of the scar (the larger and deeper wounds have higher chances for prolonged maturation).

Importantly for clinical practice, the mature scar tissue becomes functionally inert and much less responsive to therapies than the scars existing for less than one year [3]. Then, mature scars represent a therapeutically unanswered challenge and are usually considered for surgical revision [9,12]. At the same time, the surgical interventions in young scars (when the HS and keloids are less clearly differentiated [21]) are associated with the risk of excessive scarring after the excision [1,18]. Therefore, a clearer understanding of the HS maturation process is needed.

Animal models of HSs are relatively limited due to the differences in skin and subcutaneous tissue structure and other physiological aspects between humans and animals [22]. The key distinction is a higher elasticity and displacement ability of the animal skin resulting in faster wound closure in animals [23]. This is considered an important limitation in the modeling of HSs. A breakthrough model of HS was proposed by T. Mustoe and co-authors [20], who found that full-thickness ischemic wounds of the ventral side of the rabbit ears can heal with the formation of scars visually similar to the human HS. This model [20] relies on the four-six circular excisions of the skin and subdermal auricular perichondrium on the ventral side of the rabbit ears. The excisions are performed by a 6–7 mm biopsy puncher under a dissection microscope. In this model, epithelization occurred in 15–20 days and followed by the formation of scar tissue in 30–60 days with the maximum elevation of the scar at ~30 days after the operation. The model [20] was validated in more than 70 studies as a reproducible tool for the investigation of new diagnostic modalities and topical anti-scarring treatments [23,24,25]. The majority of these works were performed when the scars had the maximum height. This implies that the scar maturation was not completed yet. At the same time, the arsenal of the tools to objectively define the degree of scar maturity is limited [13,21]. Moreover, the limited duration of scar models, including the conventional one in rabbit ear, remains a serious obstacle for the extrapolation of the in vivo experimental finding to the humans [22].

2. Morphometric Analysis, Histology, and Immunohistochemistry

3. Chemical Analysis

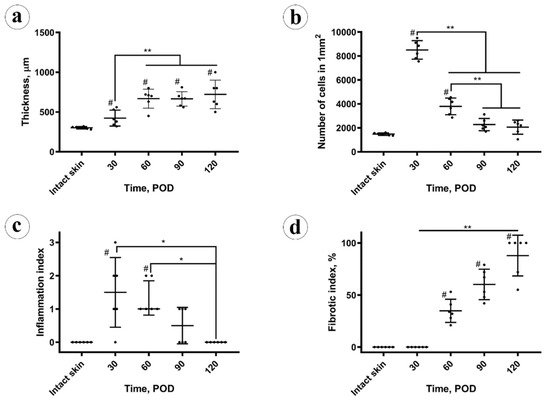

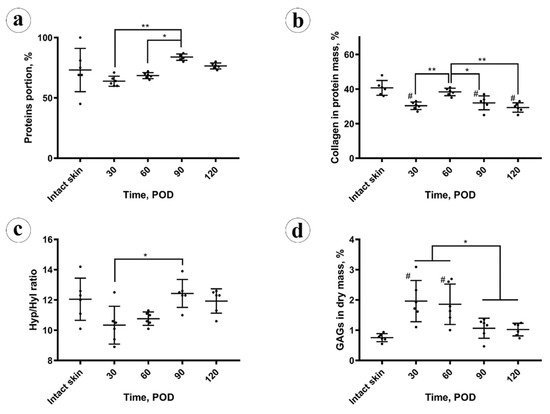

The total protein content (Figure 3a) in the intact skin was 73 ± 18% (CI 95% (54, 92)%). In the scars, on POD 30 it was slightly reduced (not at the level of statistical significance, p = 0.103), comparing to the intact skin 64 ± 4% (CI 95% (59, 68)%). It gradually, not statistically significantly (p = 0.087), increased to 69 ± 2% (CI 95% (66, 71)%) on POD 60. Next, on POD 90, the protein amount grew up to 84 ± 3% (CI 95% (81, 87)%), overcoming the values previously observed in the scars and skin (p < 0.001). On POD 120, it statistically significantly decreased (p = 0.003), comparing to POD 90, and measured 77 ± 2% (CI 95% (74, 79)%), approaching the value observed in the intact skin. The total protein content in the experimental scars positively correlated with the scar thickness (Rs = 0.566, p = 0.004) and the fibrotic index (Rs = 0.738, p < 0.001), while was strongly negatively associated with the cellularity (Rs = −0.747, p < 0.001) and inflammation (Rs = −0.520, p = 0.009).

The collagen content (Figure 3b) in the protein mass of the scars on POD 30 was significantly (p < 0.001) lower than in the intact skin (30 ± 3%; CI 95% (28, 33)% vs. 41 ± 4%; CI 95% (36, 45)%, respectively). On POD 60, collagen amount in scars increased to the skin-matching level 38 ± 2% (CI 95% (36, 41)%) and then gradually decreased to 32 ± 4% (CI 95% (28, 36)%) on POD 90 and 29 ± 3% (CI 95% (27, 32)%) on POD 120, finally dropping below the intact skin measurements. The amount of collagen in the protein mass of the scars did not correlate with the scar thickness, fibrotic index, cellularity, inflammation, and total protein content.

Amino acid analysis results are demonstrated in Figure 3c. A statistically significant decrease in the molar hydroxyproline to hydroxylysine (Hyp/Hyl) ratio in the scars (10 ± 1%) vs. intact skin (12 ± 1%) was found on POD 30 (p = 0.048) and on POD 60 (11 ± 1%; p = 0.044). This ratio returned to the normal skin values on POD 90 and POD 120 (12 ± 1%). The Hyp/Hyp ratio in the scars positively correlated with the total amount of protein (Rs = 0.596, p = 0.002) and fibrotic index (Rs = 0.606, p = 0.02) and negatively with the cellularity (Rs = −0.509, p = 0.011). There were no statistically significant correlations between the Hyp/Hyl ratio and scar thickness, inflammation, and collagen content.

The amount of sulfated GAGs in the scar dry mass (depicted in Figure 3d) was sharply and statistically significantly (p = 0.002) increased in the scars on POD 30 (2.0 ± 0.7%), in comparison with the intact skin (0.8 ± 0.1%). On POD 60 it equaled 1.9 ± 0.7% (no statistical difference vs. POD 30), and then decreased to 1.1 ± 0.3% on POD 90 and 1.0 ± 0.1% on POD 120. The drop of GAGs content between POD 60 and POD 90 was statistically significant (p = 0.027), while later the concentration of GAGs was statistically unchanged. The GAGs amount positively correlated with the cellularity (Rs = 0.698, p < 0.001) and the inflammation (Rs = 0.543, p = 0.06). Negative correlations were observed between the GAGs content and the thickness of scars (Rs = −0.428, p = 0.037), fibrotic index (Rs = −0.626, p = 0.001), total protein amount (Rs = −0.597, p = 0.002), and Hyp/Hyl ratio (Rs = −0.509, p = 0.011).

4. Discussion

In this study, the process of HS maturation was modeled and systematically explored.

Conventionally, the rabbit ear HS model is used for the evaluation of various treatments targeting the process of scar formation [19]. The treatment usually starts on POD 30 and continues for the next four weeks [4,7,14,15,16,17,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. The results of the current study show that during this period, the scar is not stable yet. This implies that many treatment effects reported in the respective literature occur on the background of the natural scar maturation. Whether the proposed treatment is equally efficient in the old, mature HSs remains an open question.

Here, we extended the period of observation of rabbit ear HSs up to POD 120. Only a few brief reports have been published before our work on the structure of the rabbit ear HS scars existing longer than two months since experimental wounding [20,37]. Previously, to create such long-lasting scars, the large (1.5–2 cm × 4.5–7 cm) full-thickness excisional/electrocauterized wounds were made on the ventral side of rabbit ears instead of punch biopsies, and the histological data on these scars was fragmentary [20]. The authors reported the elevation of the scar above the skin level, organization of fibrosis, mild inflammatory signs in the scar tissue and thickening of the subdermal cartilage during the period to POD 90 (without specific staging), while the macroscopic observations continued for approximately nine months. The large size of the wounds and the alternative surgical technique made this chronic scarring model less reproducible than the classical approach; the further usage of this chronic HS model was minimal. In the present work, we challenged ourselves to reconcile the need in a mature HS model with the reproducible surgical methodology and rational observation time (4 months). We achieved this by a minor increase of the punch biopsy wounds diameter (from 7 to 10 cm). By the application of the quantitative and semiquantitative methods for the objective evaluation of the scars, we identified four stages of the rabbit ear experimental HS maturation.

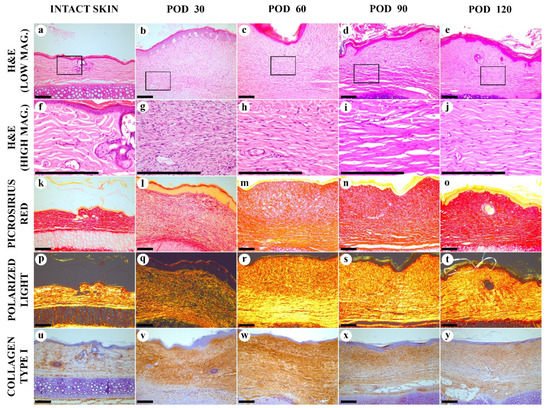

Stage 1, the early immature scar. On POD 30, the scar tissue was immature. It consisted of the densely vascularized organizing granulation tissue with very high cellularity and increased inflammation. Biochemical signature included the reduced total protein and collagen contents, decreased Hyp/Hyl ratio, and sharply enlarged amount of GAGs. The scar was thicker than the intact skin, while there were no organized fibrous collagen bundles with parallel alignment yet, and the polarization light luminescence of collagen stained with PSR was dim and diffuse. Thermal analysis revealed the loss of the two skin-specific thermal transitions on the DSC curve and the formation of the single peak at ~61 °C; that corresponded to the large fraction (~50%) of immature collagen.

Stage 2, the late immature scar. Between PODs 30 to 60, the scars underwent intensive changes. The thickness of the scar increased, while the cellularity and the inflammation index reduced. The total protein content started to rise, while the collagen amount was restored at the level of the intact skin. There was an increase of the fibrotic index. A gradual formation of the layered scar structure was visible by polarization microscopy. The IHC expression of collagen type I was relatively increased across the whole scar. The Hyp/Hyl ratio was lower than in the skin. The fraction of immature collagen (by DSC) was still much higher than in the skin. This can be explained by the low activity of lysyl oxidase at the early stages of fibrosis of granulation tissue [38], resulting in the reduced amount of crosslinked collagen in 4–10 times [23]. The amount of GAG still was very high.

Stage 3, the early mature scar. Between PODs 60 to 90, the scar thickness stabilized, the cellularity decreased, and the inflammation almost disappeared. Two layers of the scar tissue became visible by H&E, while the polarization microscopy revealed an almost homogenous bright luminescence in PRS-stained samples. The fibrotic index continued to grow. There was a notable change of the collagen bundles alignment to a more parallel one that was previously defined as one of the signatures of HS [39]. The total protein content grew, and the amount of GAGs and collagen type I expression continued decreasing. Hyp/Hyl ratio and the DSC signature approached the skin values. The observed dynamics of GAGs content corresponds to the previously reported data on the concentration of chondroitin-sulfate in the granulation tissue and immature HSs (six times higher than in the skin) and mature scars (slightly higher than in the skin) [6]. The changes in the Hyp/Hyl ratio revealed during the 90 days post-wounding could be attributed both to a shift in the ratio of collagen types [40] and a change in the activity of prolyl and lysyl hydroxylases and lysyl oxidase [38,41]. In the current study, the Hyp/Hyl ratio in scars mostly remained close to the values of normal skin [42] and dropped below the “skin range” only in the first two stages of scar maturation (up to POD 60). This reduction in Hyp/Hyl ratio may be associated with a possible increase of the relative amount of collagen type IV due to a high content of vascular elements (the commonly known localization of this collagen type) as it is characterized by a low Hyp/Hyl value (2.6–3.0) [42]. It is likely that the Hyp/Hyl ratio grew during stage 3 of scar maturation (PODs 60–90) due to the temporary increase of the amount of collagen type III, which has a high Hyp/Hyl value (22.0) [42].

Stage 4, the late mature scar. On PODs 90 to120, the scar thickness was stable, and the cellularity almost did not change, as well as the inflammation index, while the fibrotic index was increasing. The upper and bottom layers of the scar tissue were not further discernible histologically. The organization and alignment of collagen bundles are enhanced. Collagen I expression slightly reduced, comparing the earlier stages of scarring. Moreover, the total protein collagen content diminished, while the Hyp/Hyl ratio did not change much. GAGs amount and the immature collagen fraction (defined by DSC) remained unchanged. This corresponds with the 2–2.5 times increase of lysyl oxidase in 3-month-old human postburn scars compared to normal skin as reported earlier [38]. The restoration of the normal skin Hyp/Hyl ratio in scar tissues observed by POD 120 may indicate the re-balancing of the production of key macromolecules that determine the formation of collagen fibers.

We propose several interpretations of correlation analysis results relevant to the mechanisms of scarring and the possible implications for further HS modeling and treatment.

First, we found that the thickness of the scar was continuing to grow between POD 30 and 60, while the peak value of cellular density was achieved on POD 30 and decreased later. This indicates that cellular hyperplasia was not responsible for the scar volume increase at least after POD 30. Moreover, the absolute values of the Rs indicated that the thickness of the scars was more dependent on the extracellular matrix changes (fibrotic index) rather than on the fibroblast cellular dynamics and inflammation. At the same time, the fibrotic index strongly negatively correlated with the cellularity and inflammation index.

Next, the most notable increase in the total protein content was observed during stage 3 of scar maturation (POD 60 to 90). Then, some decrease in protein concentration was detected. This corresponded with the organization of the two-layered structure with thick collagen bundles followed by its remodeling into a more homogenous and regular collagen framework with thinner bundles that may be attributed to the activity of metalloproteinases. Total protein content, scar thickness and the fibrotic index correlated positively with each other and negatively with the cell density. This means that the increased protein amounts, the scar volume, and the fibrosis were supported not by the fibroblast hyperplasia (the increase in numbers) but by the hypertrophy of the cells (enhanced functional efficacy, which is usually associated with enlarged dimensions of the cells). It seems rational to suggest that the cytostatic and anti-inflammatory treatment of the scars may result in an increase of the total protein content or the acceleration of the organization of fibrosis, contributing to the overall scar maturation. Interestingly, the collagen content did not correlate with the scar thickness, fibrotic index, cellularity, inflammation, and total protein content. This may testify to the role of non-collagenous compounds, possibly of proteinaceous nature (e.g., proteoglycans, glycoproteins, or enzymes), in the formation of the scar volume.

Finally, a sharp increase in the content of sulfated GAGs positively correlated with cellularity and inflammation and negatively associated with the scar thickness, fibrotic index, and total protein amount. This indicates that GAGs are unlikely to be the non-collagenous extracellular matrix component responsible for the scar prominence. Importantly, the accumulation of GAGs and protein in the scars was separated in time. The GAGs were increased up to POD 60, whereas after this time point, GAGs concentration reduced, while the protein accumulation grew dramatically. This corresponds with the previously shown accumulation of sulfated GAGs in granulation tissue [6] and in immature HSs [43]. It seems reasonable to suggest that GAGs as highly polar water-binding compounds work in the immature scars for the mechanical stress distribution over an increased volume when the structural components of the scar are not sufficient to bear the tension. This is similar to the “shock absorbers” function of GAGs described, first of all, in cartilage [44]. The molecular mechanisms behind the apparent switch from GAGs to protein accumulation in the maturating HS are not clear yet. Different rates of GAG and protein synthesis and transformations are thought to be among the factors that can contribute to this. However, the estimation of the rates and energy costs of these processes is complicated, as numerous conditions can affect them [45,46].

We think that these findings provide the rationale for the stage-specific scar-reduction therapeutic strategies. For example, GAGs potentially can be targeted at stages 1 and 2 of scar maturation by physical therapies that promote the redistribution of water bound by GAGs and activate the mechanosensory responses of cells [47]. Alternatively, various pharmacological strategies can be applied to control GAGs metabolism or local concentration [46,48]. Despite some potentially positive changes such as an increase of the elastic fibers content or clinical improvement was observed after the treatment of early HS with chondroitinases in a conventional rabbit ear model [49] and in human keloids [50], respectively, the GAG-reducing approach requires certain caution and further studies as it may result in significant changes of the biomechanical and humoral signaling balance following the release of the growth factors from the GAG-associated depot and redistribution of the mechanical tensions due to displacement of unbound water [44,51]. Moreover, recent data show that highly sulfated chondroitin sulfate may protect fibroblasts of the HS from activation of alpha-smooth actin expression after stimulation by transforming growth factor-beta, the major regulator of fibrosis [52]. In this study, we did not identify the individual GAG types as this question has been addressed in several studies [6,43,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. However, our current findings clearly point to the role of GAGs in HS maturation, and therefore we expect that further, more targeted research in this area may help for better control of the scar tissue remodeling.

On the other hand, the correction of the protein composition and turnover, for example, via the biological approaches such as the control of cellular phenotype and secretion profiles [67] or ECM remodeling [68,69], looks more justified at the later stages of scarring, which are more relevant to the tasks of the reconstructive and plastic surgery. Considering our findings point to the role of non-collagenous protein components of ECM in the increase of the thickness, it looks especially promising to explore the scar matrisome components beyond the collagens. With this regard, the -omics technologies enhanced with data science methods [70,71] may play a key role in the identification of new targets for scarring control in the ECM milieu.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biology10020136