Chronic kidney disease, also referred to as end-stage renal disease (ESRD), is a prevalent and chronic condition for which treatment is necessary as a means of survival once affected individuals reach the fifth and final stage of the disease. Dialysis is a form of maintenance treatment that aids with kidney functioning once a normal kidney is damaged. There are two main types of dialysis: hemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD). Each form of treatment is discussed between the patient and nephrologist and is largely dependent upon the following factors: medical condition, ability to administer treatment, supports, geographical location, access to necessary equipment/supplies, personal wishes, etc. For Indigenous Peoples who reside on remote Canadian First Nation communities, relocation is often recommended due to geographical location and limited access to both health care professionals and necessary equipment/supplies (i.e., quality of water, access to electricity/plumbing, etc.). Consequently, the objective of this paper is to determine the psychosocial and somatic effects for Indigenous Peoples with ESRD if they have to relocate from remote First Nation communities to an urban centre. A review of the literature suggests that relocation to urban centres has negative implications that are worth noting: cultural isolation, alienation from family and friends, somatic issues, psychosocial issues, loss of independence and role adjustment. As a result of relocation, it is evident that the impact is profound in terms of an individuals’ mental, emotional, physical and spiritual well-being. Ensuring that adequate social support and education are available to patients and families would aid in alleviating stressors associated with managing chronic kidney disease.

- chronic kidney disease

- renal failure

- end-stage renal disease

- dialysis

- indigenous

- northern

- canadian

- rural

- remote

- urban

- relocation

- first nation

. Introduction

According to The Kidney Foundation of Canada [1], approximately 1 in 10 Canadians have kidney disease and millions more are at risk. In fact, the number of individuals living with kidney disease has increased 37% since 2007 and approximately 48,000 Canadians are receiving treatment for kidney failure [1]. Unfortunately, Indigenous Peoples, who compromise 4.3% of Canada’s population (over 1.4 million people), have a disproportionately high rate of kidney disease in comparison to non-Indigenous Peoples [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Statistics demonstrate that between the years 1980 and 2000, the number of Indigenous peoples receiving dialysis increased 8-fold [5,8]. Additionally, Indigenous Peoples are four times more likely to experience end-stage renal disease (ESRD) than non-Indigenous People [5,6,9]. According to Sood and colleagues, the Indigenous Peoples of Canada experience “a high burden of illness, low socio-economic status and geographic isolation” ([10], p. 1433). Consequently, this contributes to an increased prevalence of diabetes mellitus, obesity and hypertension which are some of the leading risk factors to kidney disease and renal failure. This combination of medical and societal factors, in conjunction with delayed access to a nephrologist, contribute to the increasing prevalence of ESRD [5]. Unfortunately, it is evident that individuals who reside in remote locations who are in need of dialysis treatment often have limited choice and frequently have to leave their communities and relocate to urban centres [9].

2. Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

Chronic kidney disease (CKD), also referred to as chronic kidney failure (CKF), occurs when the functioning of a kidney progressively deteriorates. Kidneys function to filter wastes and excess fluid from the blood, which are later excreted in the urine. However, as CKD progresses and kidney functioning declines, harmful levels of fluid, electrolytes and wastes can accumulate in our bodies which can be detrimental to our health [11]. A diagnosis of CKD puts individuals at an elevated risk of cardiovascular diseases which include increased chances of cardiac arrest or stroke.

2.1. Stages of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

CKD consists of five stages, ranging from mild to severe loss of kidney function. This is determined based on an individual’s glomerular filtration rate (GFR) which is a measurement (in milliliters per minute) that determines the rate at which kidneys filter wastes and extra fluid from the blood [12]. Additional indicators of CKD (which must be present for approximately three months) include the presence of albuminuria in urine, urine sediment abnormalities, electrolyte imbalances, histologic abnormalities, structural abnormalities, and/or history of kidney transplant [13]. When kidney functioning deteriorates to approximately 30% of normal, individuals with CKD often experience symptoms of uremia which includes “weakness, nausea, loss of appetite and a bitter taste in the mouth” [14] (p. 3). However, when kidney functioning declines to 10–15% of normal, this indicates that the individual has reached the fifth and final stage of CKD, also referred to as End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) or kidney failure. At this stage, individuals require treatment for survival [14]. For further information regarding the stages of CKD and the diagnostic criteria, please refer to the KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease ([13], p. 5).

2.2. Forms of Treatment

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is an incurable “progressive and debilitating chronic illness” that requires treatment ([15], p. 1312). There are two forms of treatment available: dialysis or kidney transplant. For the purposes of this paper, dialysis treatment will be the primary focus.

Dialysis is a form of treatment that replaces some of the functioning of a normal kidney when it becomes damaged [16]. Dialysis prevents toxic build-up in our bodies by filtering waste, salt and extra water and by keeping a safe level of certain chemicals in our blood (i.e., potassium, sodium and bicarbonate) [17]. As previously mentioned, dialysis is typically required when the individual experiences kidney failure (ESRD) or when 10–15% of their kidney functioning is remaining. At this point, the individual would require dialysis for the rest of their life as maintenance, or receive a kidney transplant if deemed eligible [14]. Dialysis treatment does not have a reverse effect on kidney function. Unfortunately, there is no cure [18,19]. Individuals typically receive dialysis in hospital settings, on a dialysis unit that is not affiliated with a hospital, or in their home. The nephrologist (a physician who specializes in kidney functioning) and patient collaboratively determine the best location to receive treatment based on the individual’s medical condition and personal wishes [16]. However, if the individual is incapable of performing dialysis independently or lacks support from family or friends, hospital or dialysis units are strongly recommended due to the complexity of the dialysis routine [17]. Lastly, unless a donor kidney is readily available for an eligible patient, that individual would require a form of dialysis as they await surgery [9,18]. This option does not appear to be favourable to some cultures, including Indigenous Peoples, due to perceptions and beliefs regarding organ donation [20].

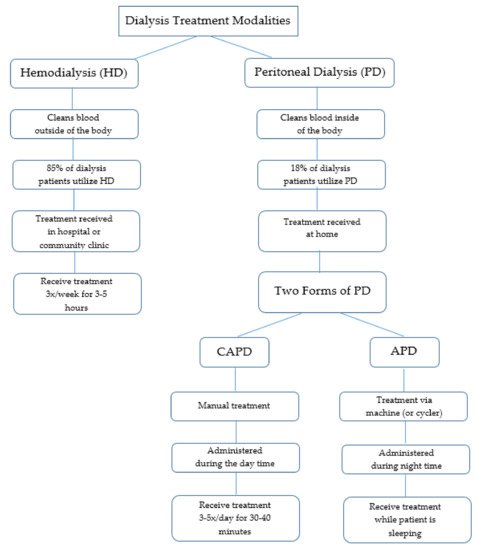

Hemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD) are the two main types of dialysis (Figure 1). According to Murphy and colleagues, these forms of treatment are “very different in terms of technique and physiology” ([21], p. 2557). Each method of dialysis has differing risks and benefits [10] and there is very little evidence that indicates whether either method is clinically superior [22]. Both forms of treatment require close and continuous monitoring by a nephrologist to ensure effective treatment and to address any complications that may arise [23]. Again, the type of dialysis a patient receives is dependent upon discussion between the patient and nephrologist. Additional factors that may influence treatment modality include the patient’s ability to adequately perform treatment, additional medical comorbidities, or geographic location [21]. Evidently, the process of determining the best treatment modality for patients can be complex due to each individual’s unique needs and circumstances.

Figure 1. Overview of dialysis treatment modalities.

2.2.1. Hemodialysis (HD)

HD is a form of treatment that cleans blood outside of the body. In this process, a machine and filter are used to remove waste products and excess water from the blood [16]. Hemodialysis is reportedly the most common treatment for patients with ESRD [4,14]. In fact, approximately 85% of patients with ESRD in Northeastern Ontario use this form of treatment [4]. HD patients typically receive treatment in a hospital or community clinic three times per week (Monday, Wednesday, Friday, or Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday) for approximately four hours at a time, although this can range from three to five hours [14,15,16,17,18,19].

2.2.2. Peritoneal Dialysis (PD)

PD cleans the blood internally utilizing a fluid (dialysate) that is inserted into the abdomen via a catheter to discard waste products and excess fluid from the body [16]. In Canada, approximately 18% of all dialysis patients receive PD as treatment [10]. PD enables patients to be treated in their own homes, which promotes independence. However, PD patients are also periodically seen in an ambulatory clinic setting for review [10]. Two forms of PD are available: Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis (CAPD) and Automated Peritoneal Dialysis (APD) [17].

CAPD requires patients to hook the dialysate to their catheter manually to drain the fluid once the exchange is complete. While this treatment allows patients to complete normal activities, CAPD does require three to five thirty to forty minute exchanges every twenty four hours [17].

In contrast, APD is completed via a machine (or cycler) that delivers and drains the dialysate automatically. Administration occurs during the night while the patient is sleeping. Evidently, the only difference each form of PD treatment is the number of treatments and the process in which the treatment is completed [17].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph18073838