The gut microbiota is the set of microorganisms that colonize the gastrointestinal tract of living creatures, establishing a bidirectional symbiotic relationship that is essential for maintaining homeostasis, for their growth and digestive processes.

- gut microbiota

- bipolar disorder

- mood

- anxiety

- mania

- depression

1. Introduction

1.1. Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar Disorder (BD) is a severe and chronic mood disorder defined by alternating episodes of mania, hypomania, and depression. It is widely diffused with a prevalence of more than 1% [1].

Manic or hypomanic episodes are characterized by elevated mood and increased activity; they differ in severity and length, with manic episodes being more severe than hypomanic ones. At the onset of the disorder, most patients with BD present a depressive episode, subtly differing from unipolar depressive ones [2].

As to pathogenesis, BD is a highly heritable disorder and a multifactorial model of gene and environment interaction has been proposed [3]. An imbalance in monoaminergic systems, as the serotonergic, dopaminergic, and noradrenergic neurotransmitter systems, plays a key role in the disorder [4]. Neural plasticity seems also to be important in the circuitry regulating affective functions, with neurotrophic molecules, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), having a vital role in dendritic sprouting and synaptic plasticity [5].

Apart from this evidence, several studies conducted over the last few years have evaluated the possible implications of the gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of BD [6,7].

1.2. Composition and Development of the Gut Microbiota

The microbiota represents the set of microorganisms present in an environment [8,9], with the intestinal one including at least 1000 different species. These microorganisms express more than 3 million genes that take the name of the microbiome and which, according to some researchers, represent our second genome [10,11,12].

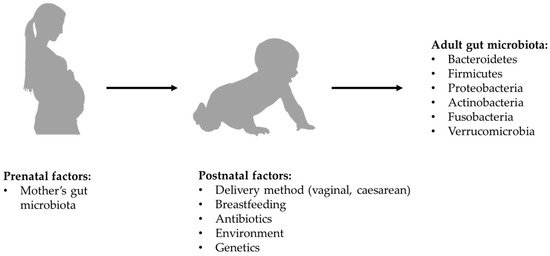

Bacteria (especially the obligate anaerobes), as well as viruses, protozoa, archaea and fungi, participate in the constitution of the microbiota [10,13]. The bacteria mainly belong to two phyla, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes [14] and, even if to a lesser extent, the Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria and Verrucomicrobia phyla are also present [15].

According to most of the current evidence, microbial colonization of the gastrointestinal tract begins at birth, so the way in which delivery is carried out might affect the composition of the microbiota. Specifically, in the case of vaginal birth, the new-born is exposed to the mother’s vaginal microbiota, while in the case of a caesarean section it is exposed to the mother’s skin microbiota [16,17]. However, there is more recent evidence that new-borns begin to acquire their microbiota in utero through the microbes which, crossing the maternal digestive tract, are thought to colonize the digestive tract of the embryo. Regardless of what the exact timing of colonization may be, the composition of the newborn’s microbiota is influenced by maternal diet and lifestyle [18], as well as by the duration of postpartum hospitalization, by the possible use of antibiotics and by the type of breastfeeding. In full-term babies born from vaginal birth and exclusively breastfed, the microbiota has a composition in which beneficial species prevail and Clostrioides difficile and Escherichia coli are marginally present. After the first 2 weeks of life, the intestinal microbiota seems to acquire relative stability all through the weaning period, with further changes which, although less significant, continue to occur until the 5th year of age [19,20] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Formation of bacterial component of gut microbiota.

At this point, the composition of the child’s microbiota is essentially comparable to that of an adult, in which its configuration’s main determinant seems to be the diet [21]. The role of dietary-nutritional factors continues to be influential even in the elderly where, among other things, the composition of the microbiota is strongly correlated to the individual’s health state and levels of frailty [22]. It is believed that the quality of human relationships can also modulate the composition of the microbiota. In this regard, a recent study found that married couples who live in a very close relationship have a very similar composition of the microbiota [23].

1.3. Function of Gut Microbiota

The microbiota establishes a symbiotic relationship with the host organism, essential for maintaining homeostasis, as well as growth and digestive processes [24,25]. In detail, the microbiota plays a crucial role in preserving the barrier of the gastrointestinal epithelium, regulating its permeability (through the different expression of proinflammatory cytokines and NF-kB), the luminal absorption of water, the electrolytes and nutrients, and exerting a mechanical defense action against the entry of toxins and pathogens. The bacteria that constitute it modulate the integrity of the narrow intestinal junctions, inhibit the adherence of pathogens to the intestinal barrier, and increase the production of mucin from the goblet cells, the secretory IgA and the secretion of β-defensin in the mucus luminal [26].

The microbiota also appears to be involved in the regulation of various functions of the gastrointestinal lymphoid tissues (GALT) [24]. In support of this last consideration, a study conducted on a large sample of 1,937,488 subjects, 44,259 of which underwent an appendectomy in paediatric age, showed that the latter, compared to controls who have had previous appendicitis, or in healthy conditions or undergoing surgery for hernia abdominal, manifested an increased risk for developing psychological symptoms. Hence, the caecal appendix can act as a reservoir that guarantees the balance of the microbiota in case of dysbiosis [27].

1.4. Dysfunctions of Gut Microbiota

The alteration of the symbiotic relationship existing between the microbiota and the host organism takes the name of intestinal dysbiosis and, on the basis of the evidence currently available, it is presumably involved in the development of various gastrointestinal and extra-gastrointestinal disorders; these may include neuropsychiatric disorders. [28,29].

In the specific case of psychiatric disorders, the pathogenetic role of the microbiota could be traced back to its ability to influence the development and the function of the CNS, as well as other relevant behavioral aspects. This ability can be traced back to the modulatory action that the microbiota exerts at the level of the bidirectional communication system that exists between the intestine and the brain, which is called the gut–brain–microbiota axis [30,31].

The mechanisms through which the microbiota performs its function at the level of the aforementioned axis include those of immunological, endocrine, neuronal and vagal autonomic stimulation nature [32].

1.5. Aims

Considering the possible implication of microbiota in the development of neuropsychiatric disorders, we focused our attention, reviewing in a narrative way the relevant literature, on the possible correlations between the gut microbiota and BD. Our first aim was to explore pathogenetic links between microbiota and BD and which alterations in the composition of the microbiota itself are associated with the disorder and its different phases. We also reviewed the evidence about the alterations of microbiota linked to the use of psychotropic drugs currently available to treat BD. Finally, the therapeutic potentials of microbiota manipulation for the treatment of BD were reviewed.

2. Microbiota and Bipolar Disorder

2.1. The Pathogenetic Role of the Gut Microbiota in Bipolar Disorder

Considering the feasible implications of the microbiota in the pathogenesis of BD, it could be regarded as a possible modulator for the inheritance of such disorder. With respect to this, it may be interesting to analyze the study by Vinberg et al. which compared the gut microbiota’s composition in pairs of monozygotic twins, that were discordant and concordant for affective disorders, with that of pairs of monozygotic twins with no history of affective disorders. The results of the aforementioned study showed that sick twins, compared to healthy ones, had less microbial diversity and absence of Christensenellaceae family and that these alterations could constitute a vulnerability marker for the development of BD in genetically predisposed subjects [33].

Considering that BD is characterized by the presence of a low-grade inflammatory state [34,35], the microbiota could be involved in the development of such disorder through the modulation of the immune response. In detail, the intestinal microbiota, through the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) is involved in the modulation of the innate component of the immune response. TLRs, expressed on innate response cells and on neurons and glial cells at the CNS level, are involved in the recognition of specific constituents of Gram-positive bacteria and Gram-negative lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The activation of the aforementioned receptors induces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6) which, by exploiting the areas of greater permeability at the level of the Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB), can exercise their action at the level of the CNS [25,36,37]. In relation to this, the presumed role of antibiotic therapy in inducing acute manic episodes in patients with BD should be taken into consideration [38]. Specifically, in a study conducted on 234 patients hospitalized for acute mania, the prescription rate of recent antibiotic therapy was significant and it was associated with greater severity of manic symptoms [39]. The correlation that exists between BD and gastrointestinal inflammatory diseases must also be acknowledged to reinforce the existence of a relationship between microbiota, BD and the immune response. Inflammation is often measured on the basis of the biomarkers of the microbial translocation process. The panel of markers used to diagnose Chron’s disease, for example, includes the detection of antibodies against the Saccharomyces cerevisiae, an organism that is part of the normal gut microbiota.

The presence of antibodies against this yeast is probably a response to its presence in the mucous–blood interface, which is compromised in the inflammatory state. More often, BD patients have elevated levels of antibodies against the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, especially at a time that is close to the disease onset [40,41]. A further mechanism through which the intestinal microbiota could correlate with the pathogenesis of BD is the alteration of the synaptic pruning process [40]. In humans gut microbiota interferes with microglial cells in the synaptic pruning process during critical periods of development, having a direct effect on neural circuits. Of consequence, some alterations in microbiota composition can change the function of these circuits. Interestingly the aforementioned process occurs simultaneously with the maturation of gut microbiota [42,43]. It has been shown that patients affected by BD present a developmental defect in the synaptic pruning process with consequent anomalies in the modulation of neuronal connectivity at the level of the ventral prefrontal cortex and the limbic cortex [44,45,46,47].

2.2. Composition of Gut Microbiota and Bipolar Disorder

While evaluating the composition of the microbiota in patients with BD, the study by Evans et al. (2017), in which the microbiota of patients affected by BD was analysed and compared with that of healthy control (HC) subjects, is of particular interest. Such study showed that the microbiota of the former is characterized by a reduction in Faecalibacterium, a Gram-positive microorganism with anti-inflammatory properties, and in an unclassified microorganism belonging to the Ruminococcaceae family. The reduction in Faecalibacterium appears to be related to the severity of the disorder, the presence of psychotic symptoms and presumably to alterations in sleep quality [48]. In a similar study, subsequently conducted by Painold et al., in which the reduction of Faecalibacterium in the microbiota of patients with BD was confirmed, a significant increase in organisms classified as belonging to the Actinobacteria phylum and in particular, in the Coriobacteriia class of this phylum. Actinobacteria phylum, such as the Coriobacteriia class are involved in lipid metabolism [49] and therefore are related to cholesterol levels [50]; since BD is frequently associated with metabolic alterations, this could be the reason for their greater representation in patients with BD.

On the other hand, considering the relationship BD-increased risk of obesity [51], it was found that the microbiota of patients with higher BD and Body Mass Index (BMI) harboured a significantly greater quantity of lactobacilli than the group with lower BMI; moreover, the Lactobacillaceae family and the genus Lactobacillus were more abundant in the microbiota of BD patients with metabolic syndrome. Therefore, lactobacilli could be a contributing factor to obesity in BD. The increase in members of the Lactobacillaceae family, together with those of Streptococcaceae and Bacillaceae, was also associated with an increase in IL-6 levels, supporting the correlation between microbiota and inflammatory response. Furthermore, the study found a negative correlation between the alpha diversity of the gut microbiota and the disease duration [49]. However, in the 2019 study by Coello et al., which compared the microbiota of newly diagnosed BD patients with that of first degree relatives without BD and with that of HC subjects, a reduction of Faecalibacterium in the microbiota of patients with BD, highlighted by previous studies, and in those of patients affected by Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) [52], was not found.

Instead, an association has been reported between Flavonifractor, a bacterial genus responsible for the breakdown of quercetin (a flavonoid with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties) [53,54] and BD, especially in female smokers. Therefore, the presence of Flavonifractor could influence oxidative stress and inflammation through the breakdown of quercetin. This may reinforce the results of previous studies showing an increase in oxidative stress [55] and the presence of low-grade inflammatory status [56] in patients with BD. Based on the results of the study in question, it was not possible to conclude that Flavonifractor contributes to the increase in oxidative stress and inflammation; hence, in order to clarify a possible role, further investigations on the link between intestinal microbiota and oxidative stress are necessary. The microbiota of the affected patients’ first-degree relatives was comparable to that of healthy subjects [57]. Consistent with the above study, the one by QiaoQiao Lu et al. (2019) did not find any reduction of Faecalibacterium in the microbiota of patients with BD when compared to healthy control (HC) subjects, identifying in the former, among other things, a significant increase in Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (producer of butyrate), as well as in Bacteroides-Group Prevotella, Atopobium Cluster, Enterobacter spp. and Clostridium Cluster IV (manufacturer of butyrate) [11].

In the study conducted by McIntyre et al. in the same year, the Clostridiaceae family was quantitatively more present in patients with BD than in HC subjects. Clostridiaceae is a relatively large family of bacteria, containing more than thirty genera ranging from well-known organisms, such as Clostridium, to lesser-known genera, such as Sarcina. The diversity of organisms within this family, however, makes it difficult to identify specific markers that can link the increase in members of the Clostridiaceae family to different disease states. In the same study, Collinsella was more abundant in patients with BD type II (BD-II) than in individuals with BD type I (BD-I) [58].

2.3. Composition of Gut Microbiota and Mania

Through our review, it was not possible to identify studies that analyzed possible compositional alterations of the microbiota in bipolar patients during a manic episode. However, there is some evidence showing that bipolar patients in the manic phase have a gastrointestinal barrier with altered permeability, offering the possibility to assume that the aforementioned impairment of integrity could be traced back to compositional alterations of the intestinal microbiota. In this sense, an interesting study is the one conducted by Faruk et al. (2020) [59], on 41 patients with BD (21 in remission and 20 in manic phase) and 41 HC subjects evaluated by the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) to determine the severity of mania and depression symptoms, respectively. Mean patients’ serum levels of zonulin and claudin-5 were significantly higher than in the HC, with no difference between zonulin and claudin-5 levels between patients with manic episodes and patients in remission. Zonulin and claudin-5 are increased in patients with BD and this finding may highlight the role of intestinal permeability in the pathogenesis of BD.

Similar results were reported in the 2018 study by Rudzki et al. [60], in which patients with BD had higher serum concentrations of IgG directed towards gliadin and deamidated gliadin, when compared to controls. However, there was no difference between patients and the control group in IgA directed towards gliadin and tTG [61]. In a follow-up study, patients with manic symptoms had an IgG rise towards gliadin at baseline, which normalized after 6 months of treatment [62]. In the same study, patients hospitalized during a 6-month follow-up period were more likely to have an IgG increase against gliadin at follow-up.

2.4. Composition of Gut Microbiota and Bipolar Depression

Focusing on the depressive phase of the disorder, Hu et al. in 2019 attempted to define the microbiota composition of depressed BD patients before and after quetiapine treatment and to evaluate the association between microbiota and depressive symptoms, also considering the possibility of using the composition of microbiota as a diagnostic marker of disease and prognostic response to treatment. Bacteroidetes were prevalent in untreated depressed BD patients, while Firmicutes were prevalent in HC. In particular, compared to HC, untreated BD patients had a decrease in various butyrate-producing bacteria, including the genera Roseburia, Faecalibacterium and Coprococcus. Butyrate, at the CNS level, can modulate hippocampal function and promote the expression of BDNF, therefore, the reduction of bacteria that produce butyrate in patients with BD could contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease. In regard to treatment with quetiapine, the treated patients were found to be particularly rich in Gammaproteobacteria when compared to those not treated. In evaluating the associations between the composition of the microbiota and depressive symptoms, it was found that the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) scores were negatively correlated with the levels of Acetanaerobacterium, Anaerotruncus (belonging to the Ruminococcaceae family) Stenotrophomonas and Raoultella, yet positively with those of Acinetobacter and Cronobacter [63].

Another study by Aizawa et al. [64] examined the association between Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus counts and affective symptoms in 39 BD patients with bipolar depression (BPD) (13 BD-I; 16 BD-II according to DSM-IV) and 58 HC. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 17-item version of the HAM-D including the sleep subscale, while the YMRS was used to assess manic symptoms. Of the patients, 33 were receiving drug treatment. Comparisons of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus counts between patients and controls revealed no significant differences between the two groups. In the patient group, there was no significant correlation between bacterial count and HAM-D total score or between bacterial count and YMRS total score. The depressive symptoms subscales (i.e., sleep, activity, psychological anxiety and somatic anxiety) were examined separately and a significantly negative correlation was found between Lactobacillus count and sleep (ρ = −0.45, P = 0.01). In this study, no significant differences were found between patients with BD and HC. However, a noteworthy correlation was found between Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus counts and depressive symptoms, including disturbed sleep. Furthermore, there was a negative correlation between the Lactobacillus count and the severity of insomnia. Therefore, an increase in Lactobacilli may be useful for sleep disorders in BD.

Depressive symptoms of MDD and BPD are very much alike and, for this reason, Rong et al. [65] hypothesized that patients with MDD and BPD could have a similar gut microbiota structure, still significantly different from that of HC. Furthermore, they hypothesized nuanced differences in the gut microbiota between MDD and BPD due to the indistinguishable clinical characteristics of the depressive component. The study was conducted on patients with MMD (# 30), patients BPD (# 31) and HC (# 30) through the analysis of faecal samples. The Gini coefficient was used to assess the inequality in the different microbiota populations: a higher Gini coefficient meant higher inequality. A Gini coefficient value of zero meant absolute equality; conversely, a Gini coefficient of one represented maximum inequality. In this study, the Gini coefficient of the microbiota (Gm coefficient) was calculated from each participant’s cumulative species curve. That is, the Gm coefficient could have been an indicator of the predominance of several dominant bacteria. Gm coefficients were significantly decreased in both MDD and BPD groups. The increase in Firmicutes and Actinobacteria phyla and the decrease in Bacteroides were significant in the MDD and BPD groups. At the genus level, four of the first five enriched genera (Bacteroides, Clostridium, Bifidobacterium, Oscillibacter and Streptococcus) were found to have increased significantly in the MDD and BPD groups compared to HC. The genera Escherichia and Klebsiella showed significant changes only between the BPD and HC groups. At the species level, compared to patients with BPD, patients with MDD had a greater abundance of Prevotellaceae, including Prevotella denticola F0289, Prevotella intermedia 17, Prevotella ruminicola and Prevotella intermedia. In addition, the abundance of Fusobacteriaceae, Escherichia blattae DSM 4481 and Klebsiella oxytoca was significantly increased, while Bifidobacterium longum subsp. Infantis ATCC 15,697 = JCM 1222 was significantly reduced in the BPD group compared to the MDD group. As a result, we found that the dominance levels of the predominant bacteria in the MDD and BPD groups were significantly decreased. Furthermore, eight species or subspecies of bacteria showed biomarker potential to distinguish MDD and BPD patients.

MDD is accompanied by higher serum IgM/IgA responses directed towards the LPS of Gram-negative bacteria, suggesting greater bacterial translocation and intestinal dysbiosis; the latter can occur in bipolar BD. There are differences between MDD and BD-I and BD-II in the biomarkers of nitro-oxidative stress associated with intestinal permeability. Comparing the serum IgM/IgA responses directed to the LPS of six Gram-negative bacteria and the IgG responses to oxidized LDL (oxLDL) in 29 BP1 patients, 37 BP2, 44 MDD and 30 healthy individuals it was found that MDD, BP1 and BP2 are accompanied by an immune response due to increased LPS load, while these aberrations in the gut–brain axis are more pronounced in BP1 and melancholia. In fact, the increase in IgM/IgA responses to Pseudomonas aeruginosa significantly discriminated patients with affective disorders (MDD and BD) from controls. Patients with BP1 showed higher IgM responses to Morganella morganii than patients with MDD and BP2. Patients with melancholy showed higher IgA responses to Citrobacter koseri than controls and non-melancholic depression. The total score on the HAM-D was significantly associated with IgA responses to Citrobacter koseri. IgG to oxLDL were significantly associated with increased bacterial translocation. Therefore, drugs that protect the integrity of the intestinal barrier can offer new therapeutic opportunities for BP1 and MDD. A study by Zheng et al. [66] performed gene sequencing on stool samples using faecal 16S ribosomal RNA and found a different microbial population in the gut microbiota of healthy subjects when compared to subjects with MDD and to subjects with BPD. In comparison to healthy subjects, individuals with MDD showed altered covarying operational taxonomic units (OTUs) belonging to the Bacteroidaceae family, while for the BPD group they belonged to the Lachnospiraceae, Prevotellaceae and Ruminococcaceae families. Additionally, 26 OTUs, that can distinguish patients with MDD from those with BPD and HC, have been identified. Finally, 4 of those 26 microbial markers are correlated with disease severity in MDD and BPD [67].

Relevant for the analysis of the microbiota in BD patients is the 2019 Bengesser’s [68] study, in which an interesting comparison was made between depressed and euthymic BD patients: the study has found a reduced diversity and variance in the microbiota of subjects depressed with respect to the euthymic ones.

(References would be added automatically after the entry is online)

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22073723