Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a neurogenetic multifactorial disorder caused by the deletion or inactivation of paternally imprinted genes on human chromosome 15q11-q13. The affected homologous locus is on mouse chromosome 7C. The positional conservation and organization of genes including the imprinting pattern between mice and men implies similar physiological functions of this locus. Therefore, considerable efforts to recreate the pathogenesis of PWS have been accomplished in mouse models. We provide a summary of different mouse models that were generated for the analysis of PWS and discuss their impact on our current understanding of corresponding genes, their putative functions and the pathogenesis of PWS. Murine models of PWS unveiled the contribution of each affected gene to this multi-facetted disease, and also enabled the establishment of the minimal critical genomic region (PWScr) responsible for core symptoms, highlighting the importance of non-protein coding genes in the PWS locus. Although the underlying disease-causing mechanisms of PWS remain widely unresolved and existing mouse models do not fully capture the entire spectrum of the human PWS disorder, continuous improvements of genetically engineered mouse models have proven to be very powerful and valuable tools in PWS research.

- Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS)

- Snord116

- U-Ube3a-AS

- IPW-A

- 116HG

- mouse models

- Magel2

- PWS imprinting center (IC)

- non-coding RNAs

- Snord115

- 5-Ht2c serotonin receptor

- Necdin

- Mkrn3

1. Prader-Willi Syndrome

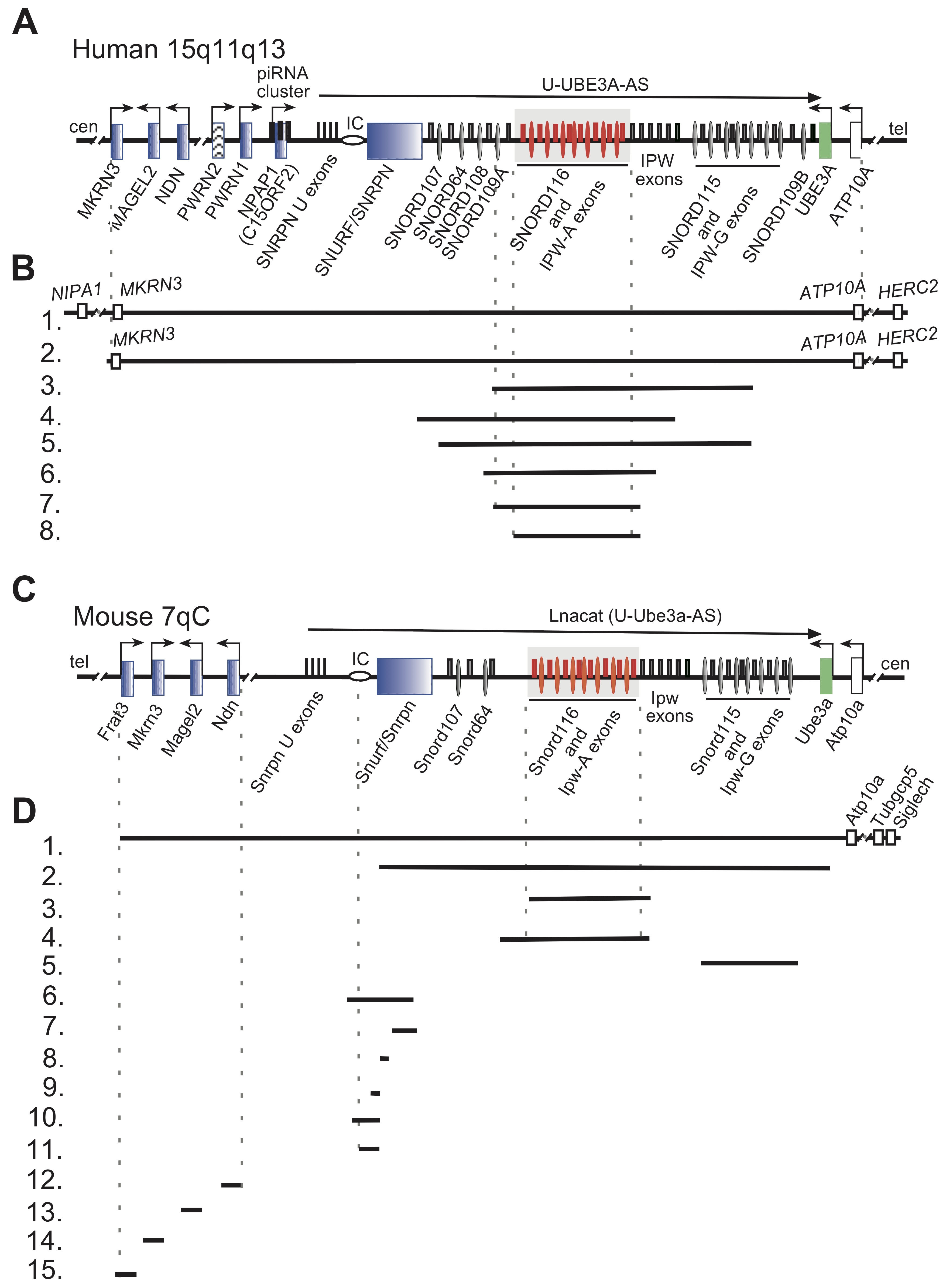

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS; MIM#176270, https://www.omim.org/entry/176270, accessed on 20 March 2021) is a rare, neurodevelopmental, multifactorial genetic disorder resulting from the deletion or silencing of imprinted genes on paternally inherited chromosome 15q11–q13 [1][2][3]. PWS is chiefly caused by a large de novo deletion on chromosome 15q11–q13 (~60–70% of cases) (Figure 1A,B(1.,2.)). Approximately 25–35% of cases are caused by maternal uniparental disomy (i.e., two copies of maternal chromosomes UPD15) [4][5]. Less than 5% of PWS patients display defects of the genomic imprinting center (IC) and cases with sporadic chromosomal rearrangements or translocations were rarely identified [5][6][7].

The complex symptomology of PWS is divided into two main and phenotypically opposing stages. The onset of the first stage takes place during the last trimester of pregnancy and proceeds into infancy until around the ninth month. It is characterized by decreased movement and reduced fetal growth in utero, neonatal hypotonia, feeding difficulties and postnatal failure to thrive. This is followed by a transitional phase lasting about five to eight years with comparatively normal weight gain. The second and final stage begins around age eight and extends into adulthood [4][8]. This stage is dominated by hyperphagia and a general lack of satiety; if uncontrolled, significant weight gain ensues transitioning into morbid obesity accompanied by all associated comorbidity risks. PWS patients suffer from general and continued developmental delay, short statue, small extremities and decreased muscle mass. They are frequently affected by respiratory malfunction symptoms, sleep disorders, hypogonadism, mild mental deficiency, and disruptions of their endocrine axis. Individuals display behavioral abnormalities including temper tantrums, obsessive compulsion and skin picking [4][9][10][11]. PWS is a complex disease, and symptoms vary considerably between patients, depending on the size of the chromosomal deletion [2][12][13]. Its prevalence ranges from 1 in 15,000—30,000 births with no observed difference between sexes or ethnicities [1][14][15][16][17]. PWS has a severe impact on the health and life expectancy of affected individuals, leading to a mortality of about 3% per year (approximately three times higher than that of the normal population). Main causes of death are related to respiratory failure, cardiovascular arrest, gastrointestinal blockage as well as infections, pulmonary embolisms and choking [18][19][20]. Therapeutic interventions focus mainly on infant feeding assistance, growth hormone replacement and endocrine dysfunction compensation as well as the treatment of various comorbidities arising from obesity [21][22][23][24]. After more than six decades of research since PWS was first described in 1956, a causative therapy does not exist (MIM#176270, https://www.omim.org/entry/176270, accessed on 20 March 2021).

2. The Prader-Willi Syndrome Locus in Mice and Men

Genomic imprinting is an epigenetic process, which via DNA and histone methylation restricts the expression of affected genes in a parent-of-origin specific manner. From the perspective of genome encoded function, the corresponding genes represent a haploid genotype. Loss of the remaining active allele results in expression defects. Historically, PWS was the first identified and characterized disease caused by an imprinting defect and/or uniparental maternal disomy [25][26]. The PWS genomic region harbors protein coding and non-protein coding genes as well as several regulatory elements that modulate imprinting and gene expression (Figure 1). The genomic structure of the PWS locus is highly conserved in mammals, with the murine PWS region on chromosome 7C being almost identical to that of human on chromosome 15. With the exception of the protein-coding gene Frat3, which is present only in mice, and reversely for rodents, no homolog to human NPAP1 (C15ORF2) and non-protein coding SNORD108 or SNORD109A-B genes could be identified (Figure 1) [27][28][29][30][31][32]. The conservation of gene organization and imprinting pattern between mice and humans implies similar physiological functions. Therefore, genetically modified mice can represent appropriate models and tools for the investigation of this disease [33].

Figure 1. Organization of human and mouse PWS loci, deletions in human and PWS mouse models are indicated. (A) Schematic representation of the human PWS locus on chromosome 15q11-q13. Blue rectangles denote paternally imprinted protein coding genes. Thin ovals show snoRNA gene locations; the imprinting center (IC) is denoted by a horizontal oval. Thin rectangles above the midline depict non-protein coding exons. SNORD116 and IPW-A exons are displayed in red and further highlighted by a grey rectangle. Arrows indicate promoters and the direction of transcription. The long arrow on top shows the putative U-UBE3A antisense transcript harboring the SNORD116 and SNORD115 clusters. Centromere and telomere regions are indicated as cen and tel. (B) Schematic representation of PWS chromosomal deletions. Lines 1 and 2 indicate the common 5–6 Mb PWS deletion [2]. Lines 3–8 represent the characterized PWS cases with microdeletion in the Snord116 array. Line 3.—[34], 4.—[35], 5.—[36], 6.—[37], 7.—[38], 8.—[39] (C) Schematic representation of the mouse PWS-locus on chromosome 7qC (symbols as above). (D) Schematic representation of available mouse models in PWS research. (1.) The largest chromosomal deletion that eliminates the PWS/AS region and a large portion of non-imprinted genes [40]. (2.) Deletion of the mouse PWS-locus span from the Snurf/Snrpn to Ube3a genes [41]. (3.) Deletion of the PWS critical region (~300 kb) (PWScr) comprising of Snord116 and IPW-A gene arrays [42]. (4.) The Snord116del mouse model eliminating a larger ~350 kb PWScr genomic region [43]. Note, that the genomic assembly of PWScr is not completed, a gap of ~50 kb inside the Snord116 cluster might increase the snoRNA gene copy number and overall size of deletion (UCSC, GRCm39/mm39 chr7:59457067- 59507068). (5.) Deletion of the Snord115 gene cluster [44] (6.–11.) Deletions within the Snurf/Snrpn and PWS IC center (Details in Figure 2). (6.) 35 kb deletion of IC center and Snurf/Snrpn exons 1–6 [45]. (7.) Deletion of Snurf/Snrpn exon 6 including parts of exons 5 and 7 [45]. (8.) Deletion of Snurf/Snprn exon 2 [41]. (9.–11.) Elimination of Snurf/Snrpn exon 1 and upstream genomic region: 0.9 kb (8), 4.8 kb (9) and 6 kb (10) deletions, respectively [46][47]. (12.–15.) Deletion of protein coding genes within the PWS-locus: (12.) Ndn [48][49][50][51]; (13.) Magel2 [52][53]; (14.) Mkrn3 [54]; (15.) Frat3 [30].

3. PWS Uniparental Disomy (UPD) Murine Models

Maternal uniparental disomy (UPD) of chromosome 15 is the second most common genetic abnormality associated with PWS and is responsible for approximately 35% of cases [5]. Mice with maternal uniparental disomy of the central region on chromosome 7 constituted the first PWS genetic model [55]. It was generated by crossbreeding animals with X-autosomal translocations of the respective region [55]. Newborn pups exhibited weak suckling activity, failure to thrive and ultimately died within two to eight days following birth. No expression of Snrpn/Snurf gene was detectable in the brain of mutant pups, suggesting an imprinting defect [55].

This very first model underlined the importance of the paternal allele in the pathogenesis of PWS in mice and defined future efforts to identify the PWS critical genomic region (Table 1).

Table 1. PWS mouse models and involved genes.

| Gene(s) of Interest. | Name, Aliases | Phenotype | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| all (UPD Chr 7) | T(7;18)50H/+ (JAX001816, https://www.jax.org/strain/001816, accessed on 20 March 2021) |

postnatal lethality (100%) growth retardation |

[55] * |

| all (6.8 Mb deletion) | PWS∆LMP2A TgPWS/AS(del) Del(7Herc2-Mkrn3)13FRdni/+ |

fetal growth retardation postnatal growth retardation neonatal lethality (100%) reduced movement irregular respiratory rate hypoglycemia pancreatic apoptosis insulin ↓, glucagon ↓ corticosterone ↑, ghrelin ↑ |

[40]* [56][57][58] |

| Frat3 | Frat3lacZ Peg12tm1Brn |

none | [30] * |

| Mkrn3 | Mkrn3m+/p− | lower weight from P45 earlier onset of puberty GnRH1 ↑ |

[54] * |

| Magel2 | Magel2m+/p− Magel2 KO C57BL/6-Magel2tm1Stw/J (JAX009062, https://www.jax.org/strain/009062, accessed on 20 March 2021) |

116HG expression ↓ postnatal lethality (~10%) reduced weight until P28 body fat ↑ lean mass ↓ bone mineral density ↓ impaired glucose homeostasis impaired cholesterol homeostasis insulin resistance leptin resistance dopamine ↓, serotonin ↓ adiponectin ↑ corticosterones ↑ oxytocin ↓ different feeding behavior less active anxiety impaired social behavior delayed onset of puberty progressive infertility |

[53] * [59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72] |

| Magel2 | Magel2m+/p− Magel2tm1.1Mus |

postnatal lethality (~50%) weak suckling oxytocin ↓, orexin-A ↓ abnormal social behavior impaired learning ability |

[52] * [73] |

| Magel2 (overexpression of truncated protein) | CAG-trMagel2 | neonatal lethality (100%) small body size, poor suckling |

[74] * |

| Necdin | Ndnm+/p− Ndntm1Alb |

none | [51] * |

| Necdin | Ndntm2Stw B6.129S1(Cg)-Ndntm2Stw/J (JAX009089, https://www.jax.org/strain/009089, accessed on 20 March 2021) |

postnatal lethality (80–95% C57BL/6 and 25% FVB) respiratory distress |

[48]* [75][76] |

| Necdin | Ndnm+/p− B6.129S2-Ndntm1.1Mus |

postnatal lethality (21–31%) respiratory distress oxytocin ↓ serotonin ↓ |

[50] * [77][78] |

| Necdin | Ndnm+/p− Ndntm1Ky |

respiratory abnormalities DRG neuron apoptosis ↑ pain sensitivity ↓ noradrenergic excitability ↓ |

[49] * [79] |

| Necdin | Ndnm+/p− Necdin KO necdin m+/p− |

unstable circadian rhythm | [80] * |

| Snurf/Snrpn Snord116 IPW Snord115 Ube3a |

Snrpn-Ube3a deletion Del(7Ube3a-Snrpn)1Alb |

neonatal lethality (80%) growth retardation hypotonia |

[41] * |

| all (IC deletion) | PWS-IC∆35kb Snrpntm2Cbr ∆PWS-IC PWS-ICdel PWS-ICdel35kb B6.129-Snrpntm2Cbr/J (JAX012443, https://www.jax.org/strain/012443, accessed on 20 March 2021) |

neonatal lethality (40–90% depending on background) growth retardation hypotonia decreased locomotive ability abnormal behavior ghrelin ↑ increased food consumption food-seeking behavior ↑ |

[45] * [81][82][83][84][85][86] |

| all (IC deletion) | PWS-ICm+/p del4.8kb PWS-IC∆4.8 Snrpntm2Alb |

neonatal lethality (40%) growth retardation |

[46] * |

| all, except Snrpn, Snord64, 116, 115 (IC deletion) | PWS-ICHs Snrpntm1Kaj |

neonatal lethality (47% C57BL/6J and 16% 129S1/Sv) growth retardation feeding difficulties |

[87] * |

| all (IC deletion) | PWS-ICm+/p∆6kb PWS-IC∆6kb B6.129S1-Snrpntm2.1Kaj/J (JAX018395, https://www.jax.org/strain/018395, accessed on 20 March 2021) |

neonatal lethality (100%) growth retardation feeding difficulties |

[47] * |

| Snord116/IPW | PWScrm+/p− Del(7Ipw-Snord116)1Jbro (distributed by TRAM Münster) |

neonatal lethality (15%) growth retardation pOx ↑, Peg3 ↑ decreased gray-matter volume altered sleep profile altered body temperature |

[42] * [88][89] |

| Snord116/IPW | Snord116del Snord116tm1Uta Snord116+/−P B6(Cg)-Snord116tm1.1Uta/J (JAX008149, https://www.jax.org/strain/008149, accessed on 20 March 2021) |

growth retardation Igf1 ↓ ghrelin ↓ impaired pancreatic development altered diurnal methylation increased anxiety altered respiratory exchange rate resistant to obesity |

[43] * [90][91][92][93][94] |

| Snord116/IPW (homozygous) | Snord116m−/p− Snord116−/− |

growth retardation fat mass ↓ increased food consumption altered diurnal activity profile resistant to obesity altered hypothalamic signaling |

[95] * |

| Snord116/IPW (only Npy+ Neurons) | Snord116lox/lox/NPYcre/+ (JAX008118, https://www.jax.org/strain/008118, accessed on 20 March 2021) |

growth retardation fat mass ↓ increased food consumption altered diurnal activity profile altered hypothalamic signaling |

[95] * |

| Snord116/IPW (adult-onset) |

Snord116 deletion | reduced food consumption insulin resistance |

[96]* |

| Snord116/IPW (adult-onset) |

AAV-Snord116delm+/p− Snord116flAAV-Cre |

increased food consumption bodyweight ↑ bodyfat percentage ↑ |

[91] * |

| Snord115 | Snord115-deficient | brown adipose tissue ↑ modest alterations in 5-Htr2cr mRNA A-to-I editing |

[44] * |

| Snord116 (single copy transgene) | no effect on phenotype | [43]* | |

| Snord116 (transgene 2 mouse, 1 rat copies) |

PWScrm+/p−TgSnord116 | no effect on phenotype | [97] * |

| Snord116 (transgene 27 copies) | no effect on phenotype | [98] * | |

| all (biallelic IC deletion) | PWS-ICm∆4.8kB/p∆4.8kB PWS-ICm∆4.8kB/p∆S-U |

rescue of postnatal lethality rescue of growth retardation |

[99] |

| Snord116/IPW (maternal IC deletion) | PWScrm5′LoxP/p− (distributed by TRAM Münster) |

Rescue of growth retardation in adult mice alterations in 5-Htr2cr mRNA A-to-I editing in the choroid plexus. |

[97]* |

| Snord116 (AAV-mediated) | Snord116delm−/p−AAV-Snord116 | energy expenditure ↑ rate of weight gain ↓ |

[100] * |

Original publications are marked by *, up- and downregulation of physiological parameters is represented by arrows (↑ and ↓).

4. PWS Large Chromosomal Deletion Models

In humans, large deletions on paternal chromosome 15q11.2-q13 were detected in more than 60% of diagnosed PWS cases—indicating that this is the most common underlying cause of the disease [5].

A mouse model with a deletion of the entire PWS region was generated more than two decades ago by microinjecting a fragment of an Epstein-Barr Virus Latent Membrane Protein 2A (LMP2A) vector into mouse zygotes (B6×SJL) F1 [40]. The resulting transgene contained a 6.8 Mb long array of ~80 repeated LMP2A copies that replaced all imprinted genes in the PWS region (Figure 1C,D; Table 1) [56]. For over four generations, the resulting transgenic PWS∆LMP2A (TgPWS) mice were bred with C57Bl/6 and subsequently with CD1 wild-type mice for the same number of generations. Finally, one stable viable transgenic mouse line derived from a single founder was established.

For TgPWS mice with a maternally inherited modified chromosome, no phenotypic abnormalities were observed. This is in stark contrast to paternal inheritance of the modified locus, which led to failure to thrive with fetal and neonatal growth retardation, reduced movement and irregular respiratory rates. Expression of all imprinted genes from the PWS locus was abolished and mice eventually died within one week of birth due to severe hypoglycaemia [57]. Deregulation of the hepatic Igf (Insulin growth factor) axis and increased concentrations of corticosterone and ghrelin were reported for mutant mice. TgPWS mice also displayed elevated levels of pancreatic apoptosis; this, in turn led to reduced α- and β-cell masses and lowered levels of pancreatic islet hormones (i.e., insulin and glucagon) [58]. The comprehensive analysis of this mouse model with a large chromosomal deletion in the PWS-locus convincingly demonstrated that the elimination of imprinted genes causes a large spectrum of PWS-related abnormalities associated within the early postnatal period.

In contrast to human, the elimination of all genes within the PWS-locus resulted in early postnatal lethality in mice, which makes it almost impossible to use this model in the detailed investigations of the complete spectrum of PWS pathogenesis. Undoubtably, however, this mouse model confirmed that these human and mouse loci are functionally similar, which justified the utilization of genetically engineered mouse models to examine PWS-related genes in order to advance our understanding of the human syndrome.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22073613

References

- Stefan, M.; Claiborn, K.C.; Stasiek, E.; Chai, J.H.; Ohta, T.; Longnecker, R.; Greally, J.M.; Nicholls, R.D. Genetic mapping of putative Chrna7 and Luzp2 neuronal transcriptional enhancers due to impact of a transgene-insertion and 6.8 Mb deletion in a mouse model of Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes. BMC Genom. 2005, 6, 157.