Melioidosis is a severe disease caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei (B. pseudomallei), a Gram-negative environmental bacterium. It is endemic in Southeast Asia and Northern Australia, but it is underreported in many other countries. The laboratory diagnosis of melioidosis is challenging due to its non-specific clinical manifestations, which mimic other severe infections. The culture method is considered an imperfect gold standard for the diagnosis of melioidosis due to its low sensitivity. Both antibody and antigen detection assays have been tested for the diagnosis of melioidosis; however it presents certain limitations in terms of sensitivity and specificity.

- melioidosis

- B. pseudomallei

- BipD

1. Introduction

B. pseudomallei is a motile, Gram-negative environmental bacterium. It is the etiological agent of melioidosis, also known as Whitmore’s disease, which affects humans and a wide range of animals such as hamsters, sheep, monkeys, and dolphins [1]. Melioidosis is highly endemic in Northern Australia and Southeast Asia, particularly in Northeast Thailand [2]. Cases are usually imported from these areas into developed countries such as those in Europe and the United States [3][4]. The case reports of melioidosis and predictive modeling studies indicate that it is present in many countries but is underreported [5]. In Malaysia, most melioidosis case reports are from hospitals and medical centers in Pahang and Sabah [6]. Globally, B. pseudomallei causes an estimated 165,000 cases of human melioidosis and 89,000 deaths each year [5]. Furthermore, it is responsible for 20% of all community-acquired septicemias and 40% of the mortality due to sepsis in northern Thailand [7].

The laboratory identification of B. pseudomallei is challenging due to its non-specific clinical signs and symptoms that commonly resemble tuberculosis. The culture of B. pseudomallei is an imperfect gold standard for melioidosis diagnosis due to its low sensitivity (70.3%) [8]. B. pseudomallei is frequently misidentified as a Pseudomonas species because of similar colony morphology in blood agar, Gram staining (Gram-negative and safety-pin appearance), and biochemical tests such as the oxidase test (oxidase positive) [9]. The detection of B. pseudomallei is difficult in routine culture media because it mimics contaminants, and the overgrowth of normal flora is observed [8]. Furthermore, the culture method is time-consuming, as it takes five to seven days and requires selective or enriched media for non-sterile samples. It also requires a class III biosafety cabinet, and experts are often unavailable in endemic areas [10][11].

The indirect hemagglutination assay (IHA) has been widely used to determine antibody titers and can be used as an indicator of B. pseudomallei exposure [12]. However, the presence of high background antibodies due to previous exposure to B. pseudomallei and closely related environmental species, especially B. thailandensis, leads to low specificity and sensitivity as well as the inability to monitor treatment responses [13]. Other potential problems with IHA are the various and unstandardized strains used for antigen preparation in different laboratories and a short shelf-life [14]. The immunofluorescent assay (IFA) and latex agglutination (LA) provide rapid confirmation of a melioidosis diagnosis, in which a monoclonal antibody (mAb 4B11) recognizes the capsular polysaccharide (CPS) of B. pseudomallei in positive blood cultures [15][16]. However, the marked disadvantages of IFA are a tendency to misidentify fluorescent debris as bacteria, and the labor- and resource-intensive methodology [11]. Furthermore, LA reagents are not commercially available and require cold-chain storage [16].

With regards to molecular methods, many types of polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) conducted by targeting various genes to detect B. pseudomallei have resulted in different limits of detection (LODs) [17][18][19]. PCR can produce false-negative results when tested on direct blood specimens due to low bacterial loads (<10 CFU/mL), which are usually below the detection limits of any PCR assay, and the presence of inhibitory substances in the blood [8]. Another diagnostic test is the InBiOS Active Melioidosis Detect (AMD), a lateral flow immunoassay (LFI) where a nitrocellulose membrane strip is coated with monoclonal antibodies (mAb 3C5) for the detection of the CPS of B. pseudomallei in clinical specimens [20]. It is a promising tool for the detection of B. pseudomallei globally and meets the criteria of being affordable, sensitive, specific, user friendly, rapid and robust, equipment-free, and delivered (ASSURED). However, it provides poor sensitivity for non-blood samples; thus, it is not yet a true point-of-care (POC) test for the diagnosis of melioidosis [11].

Various antigenic proteins have been used to develop detection methods for B. pseudomallei. One is the O-polysaccharide (OPS) component of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an appealing candidate for rapid POC tests. However, variations in the OPS antigen (type A, B, B2, or rough) among B. pseudomallei from different geographic regions result in false negatives [21]. Another protein is hemolysin-coregulated protein 1 (Hcp1), a component of the virulence-associated type VI secretion system. The Hcp1 produced by B. pseudomallei is structurally different from that of B. thailandensis; thus, seropositivity to this antigen is less prevalent than that to OPS among healthy individuals in endemic areas [12], making the use of Hcp1 preferable to that of OPS for detecting B. pseudomallei antibodies. The chaperonin GroEL is a heat-shock protein considered as a promising serodiagnosis antigen for discriminating melioidosis cases from healthy individuals [14][22]. However, Pseudomonas spp. and other Gram-negative non-fermentatives (GNFs) frequently lead to false-positive results, suggesting that the protein shares cross-reactive epitopes among these bacteria [23]. Other alternative antigens that might be useful for the serodiagnosis of melioidosis are culture filtrate (CF) and whole-cell (WC) antigens. However, these antigens have the drawbacks of unstandardized preparation methods and are therefore not reproducible across laboratories [21].

2. Type III Secretion Systems (T3SSs) of B. pseudomallei

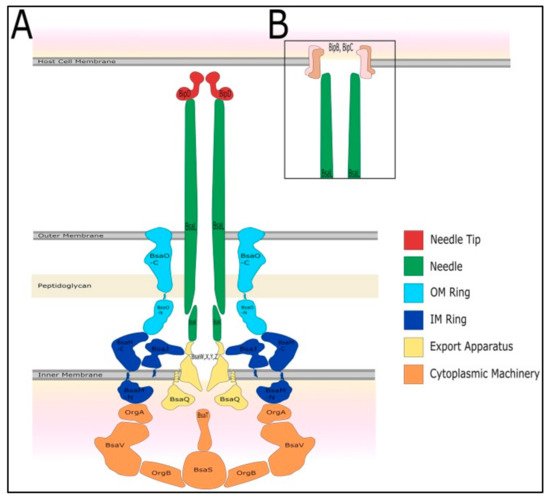

Many pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria use T3SSs to deliver effector proteins into host cells to facilitate their own survival and colonization [24]. Three T3SSs (T3SS-1, T3SS-2, and T3SS-3) are encoded in the B. pseudomallei genome on chromosome 2 [25]. T3SS-3 is the best-characterized T3SS of B. pseudomallei, and it is also known as Burkholderia secretion apparatus (Bsa). Bsa is a member of the Inv/Mxi-Spa family of T3SSs from Shigella flexneri and Salmonella spp. (SPI-1) [26]. It is often referred to as an injectisome and is composed of approximately 20 different proteins that assemble a nanosyringe [27]. Bsa comprises the structural components of the apparatus (the basal body spans both bacterial membranes, and an extracellular needle protrudes from the bacterial surface) as shown in Figure 1, secreted proteins (translocators and effectors), chaperones, and cytoplasmic regulators [28]. Similarly to its Salmonella and Shigella homologs, Bsa follows the inside-out model for its assembly [29].

Figure 1. The predicted structure of the type III secretion system 3 (T3SS-3) of B. pseudomallei. Adapted with permission from [28]. Copyright © 2017 Vander Broek and Stevens. (A) The T3SS-3 comprises of cytoplasmic machinery, export apparatus, inner and outer membrane rings, needle, needle tip (Burkholderia invasion protein D, BipD), and (B) translocon proteins (Burkholderia invasion protein B, BipB and Burkholderia invasion protein C, BipC).

3. BipD of Bsa

BipD is a dumbbell-shaped protein at the Bsa needle tip and is homologous to SipD (Salmonella) (26% identity; 36% similarity), IpaD (Shigella) (27% identity; 39% similarity), and LcrV (Yersinia) [28]. BipD is different from IpaD and SipD because it does not contain any cysteine residues; both IpaD and SipD possess one cysteine at different positions [30]. BipD serves as a platform for the assembly of the translocon pore with Burkholderia invasion protein B (BipB) (a major translocon protein) and Burkholderia invasion protein C (BipC) (a minor translocon protein). It allows for the direct passage of effector proteins into the target host cell from the cytoplasm of B. pseudomallei. The effector proteins suppress host cell processes to benefit the bacteria [28].

4. The Three-Dimensional (3D) Structure of BipD

BipD is encoded by the bipD gene, and it consists of 310 amino acids with a molecular mass of approximately 34 kDa. The precise structure of BipD was identified from a selenomethionyl-BipD (SeMet-BipD) crystal, obtained using the hanging-drop method, followed by diffraction at a resolution of 2.1 Å [31]. The Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB) Protein Data Bank (PDB) allocated accession number is 2izp for the deposited coordinates and structure factors. Another structural analysis of BipD was performed in the lipid head-group phosphocholine. This BipD crystal diffracted to 1.5 Å, followed by structural refinement at a near-atomic resolution [32]. The coordinates and structure factors were deposited in the PDB with the accession number 3nft.

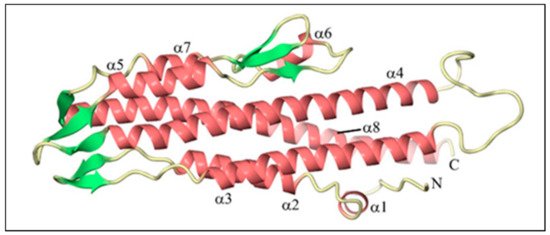

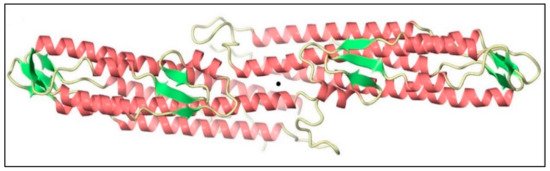

BipD is mainly composed of a bundle of α-helical segments in an anti-parallel configuration with two three-stranded β-sheet regions (Table 1): one of them at one end of the bundle, and the others on the opposite side, as shown in Figure 2. The crystal structure is consistent with far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectra, confirming the marked dominance of α-helices over β-sheets in the tertiary structure [30]. Helix 8 is a remarkably conserved part of the BipD structure, and it plays a crucial role in the formation of the dimer. Figure 3 shows two BipD molecules in the crystallographic asymmetric unit that are connected by creating extensive contacts from both subunits involving the C-terminal end of helix 8 and the N-terminal end of helix 4 in an anti-parallel manner [30]. Notably, another study also showed the dimer interface, but the only difference was that the two monomers were slightly reoriented [32].

Figure 2. The tertiary structure of Burkholderia invasion protein (BipD) generated using CueMol at 2.1 Å resolution. The pink color indicates helices, whereas the green color represents strands. Adapted with permission from [30]. Copyright © 2006 Elsevier Ltd.

Table 1. Residues of Burkholderia invasion protein D (BipD) that represent structural domains. Adapted from [30].

|

Residues of BipD |

Structural Domains |

|

36–43 |

α-helix (helix 1) |

|

47–63 |

α-helix (helix 2) |

|

64–81 |

β-hairpin (β1 and β2) |

|

82–111 |

α-helix (helix 3) runs anti-parallel to helix 2 |

|

128–170 |

α-helix (helix 4) runs anti-parallel to helix 3 |

|

171–183 |

β-hairpin (β3 and β4) |

|

184–196 |

α-helix (helix 5) runs anti-parallel to helix 4 |

|

197–203 |

β-hairpin (β5), last three residues are part of a three-stranded β-sheet with β6 and β7 |

|

209–216 |

α-helix (helix 6) |

|

220–230 |

β-hairpin (β6 and β7) |

|

233–241 |

α-helix (helix 7) runs anti-parallel to helix 5 |

|

246–250 |

β-hairpin (β8) forms a three-stranded β-sheet with β3 and β4 |

|

251–301 |

α-helix (helix 8) |

Figure 3. Two monomers of Burkholderia invasion protein D (BipD) within the crystallographic asymmetric unit generated using CueMol. The central black sphere shows that both monomers are connected by helices 4 and 8 with an approximately two-fold symmetry. Adapted with permission from [30]. Copyright © 2006 Elsevier Ltd.

5. Functions of BipD in the Pathogenesis of B. pseudomallei

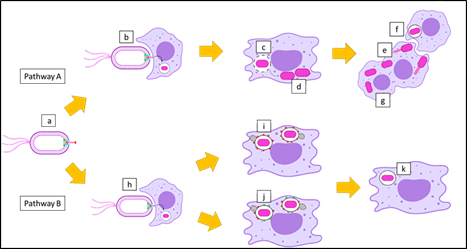

B. pseudomallei invades phagocytic cells such as polymorphonuclear leukocytes and macrophages via phagocytosis. With the help of functional Bsa, it also enters non-phagocytic cells by inducing its own uptake. B. pseudomallei escapes from the phagosome by lysing the phagosome membrane as early as 15 min after internalization, and replicates in the host cytoplasm [33]. B. pseudomallei exploits the host cell cytoskeleton by inducing actin polymerization at one pole of the bacterium to produce actin tails that propel it throughout the host cytoplasm. It also forms membrane protrusions into adjacent cells to promote cell-to-cell spread. On contact with neighboring cells, it causes cell fusion and the development of multinucleated giant cells (MNGCs) that contain hundreds of nuclei (pathway A), as shown in Figure 4 [34][35].

Figure 4. Postulation of the intracellular survival of B. pseudomallei. (a) A motile Gram-negative B. pseudomallei with Burkholderia secretion apparatus (Bsa) can use two pathways after infection of host cells. (b) Invasion of B. pseudomallei into a macrophage, where they are internalized into the phagosome. (c) B. pseudomallei escapes from the phagosome by rupturing the phagosome membrane, and (d) replicates in the cytoplasm of the macrophage. (e) B. pseudomallei forms actin tails, which leads to membrane protrusion that allows (f) cell-to-cell spread, and ultimately results in (g) the formation of multinucleated giant cells (MNGCs) (pathway A). On the other hand, (h) B. pseudomallei can be phagocytosed by a macrophage and trapped in the phagosome. (i) Bacterium-containing phagosomes undergo phagosome maturation with lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP-1). (j) In some cases, bacterium-containing phagosomes undergo LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP) processes, where phagosome maturation occurs with both LAMP-1 and microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3). (k) Finally, the macrophage destroys B. pseudomallei with the assistance of the phagolysosome (pathway B).

Figure 4. Postulation of the intracellular survival of B. pseudomallei. (a) A motile Gram-negative B. pseudomallei with Burkholderia secretion apparatus (Bsa) can use two pathways after infection of host cells. (b) Invasion of B. pseudomallei into a macrophage, where they are internalized into the phagosome. (c) B. pseudomallei escapes from the phagosome by rupturing the phagosome membrane, and (d) replicates in the cytoplasm of the macrophage. (e) B. pseudomallei forms actin tails, which leads to membrane protrusion that allows (f) cell-to-cell spread, and ultimately results in (g) the formation of multinucleated giant cells (MNGCs) (pathway A). On the other hand, (h) B. pseudomallei can be phagocytosed by a macrophage and trapped in the phagosome. (i) Bacterium-containing phagosomes undergo phagosome maturation with lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP-1). (j) In some cases, bacterium-containing phagosomes undergo LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP) processes, where phagosome maturation occurs with both LAMP-1 and microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3). (k) Finally, the macrophage destroys B. pseudomallei with the assistance of the phagolysosome (pathway B).

Some B. pseudomallei cannot escape from the phagosome due to defects in the Bsa, including the mutation of BipD. Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3), is recruited to bacterium-containing phagosomes to stimulate LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP). LC3 promotes phagosomal maturation through the recruitment of other proteins, including lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP-1). Both proteins induce the fusion of the phagosome with the lysosome, which leads to bacterial killing. The phagosome also matures into a phagolysosome with the recruitment of LAMP-1 only (Figure 4, pathway B) [36]. Several studies have been performed to assess the role of BipD in the development of melioidosis. A bipD mutant was constructed to reveal its contribution to pathogenesis, as summarized in Table 2. We conclude that BipD is a protein that can be categorized as a virulence factor because of its ability to enable the bacterium to invade non-phagocytic cells, escape from the phagosome, and induce intracellular replication. It also forms actin tails, causing cell-to-cell spread, thus allowing the bacterium to survive the extracellular environment and evade both host defenses and antibiotic treatment [37].

Table 2. Characterization of bipD mutants in the pathogenesis of melioidosis.

|

Wild-Type Strain of bipD |

In Vitro Growth Rate in LB at 37 °C |

Escape from the Phagosomes of Macrophage Cells |

Intracellular Replication |

Invasion of Cultured HeLa Cells |

Induced Membrane Protrusions and |

Association of |

Refs. |

|

10276 |

No effect |

ND |

Marked reduction in intracellular replication |

The invasion occurred at a low frequency |

No protrusions or actin rearrangements |

Increased association with LAMP-1-containing vacuoles |

[26] |

|

10276 |

ND a |

ND |

ND |

Highly significant reduction in invasion |

ND |

ND |

[38] |

|

576 |

No effect |

ND |

Low replication of the bacteria in the liver and spleen |

ND |

ND |

ND |

[39] |

|

K96243 |

ND |

Unable to escape from phagosomes and showed a high level of co-localization with LC3 |

ND |

ND |

No formation of actin tails |

Increased levels of co-localization with LAMP-1 |

[36] |

a ND: not determined; LB, lysogeny broth; LAMP-1, lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1.

6. Serological Tests

A rapid, cost-effective, and sensitive serological assay is required to diagnose melioidosis. Two studies were performed using indirect ELISA to detect specific antibodies against recombinant BipD (rBipD). The first study identified BipD-specific antibodies in the sera of culture-confirmed melioidosis patients from Malaysia, Thailand, and Australia. The BipD ELISA demonstrated moderate sensitivity (42%) but high specificity (100%). This study also showed that no detectable antibody responses were found in healthy individuals from the endemic region (Thailand) when recombinant BipD was used compared to crude antigens in IHA [40]. The other study was conducted to determine BipD-specific antibodies in patient sera from Thailand and Australia [41]. A statistical evaluation showed that ELISA had worse diagnostic accuracy than the existing IHA for the Thai serum samples: the sensitivity and specificity were 63% and 61% for the BipD ELISA, whereas they were 72% and 62% for the IHA, respectively. Similar results were shown in a statistical examination of Australian serum samples. The BipD ELISA had lower diagnostic sensitivity (75% vs. 76%) and specificity (64% vs. 99%) than the IHA that was previously conducted at Townsville Hospital [42].

The immunoblotting technique was also used to analyze BipD-specific antibodies in serum samples from Thailand [64]. An elevation in BipD sensitivity (from 78% to 100%) was obtained after the removal of the glutathione S-transferases (GST), because the presence of GST prevents the binding of BipD to antibodies. However, the specificity of BipD (91.1%) was not statistically different from that of fusion GST–BipD (90%) due to the cross-reactivity of BipD and high background during melioidosis infection. Stevens et al. found that BipD-specific antibodies could be detected using the immunoblotting method, as the serum from a convalescent melioidosis patient reacted with GST–BipD. No reactivity was observed with normal human serum [26]. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensors have become an extremely potent tool due to their high sensitivity and real-time monitoring capacity [43]. BipD antibodies were detected by SPR using serum samples from Thailand, which resulted in 100% sensitivity and specificity [44].

BipD-specific antibodies were detected with varying sensitivities and specificities based on the method performed, as shown in Table 3. The disadvantages of the serodiagnosis of BipD are the cross-reaction of BipD with other antibodies, the high seropositivity among the healthy population, and the fact that not all patients infected with B. pseudomallei produce sufficient levels of antibodies against BipD [45][44]. The main drawback of all the serological assays is that the antibodies can only be detected 7–14 days post-infection [19]. Thus, antibody-detection methods cause delays in both the diagnosis and treatment of melioidosis. Therefore, BipD can be used in antigen-detection methods for the rapid diagnosis of melioidosis.

Table 3. Serodiagnostic assays using Burkholderia invasion protein (BipD) as the target.

|

Methods |

BipD |

Population |

Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

Refs. |

|

ELISA |

Histidine-BipD (His–BipD) |

Malaysia, Thailand, and Australia |

42 |

100 |

[40] |

|

ELISA |

His–BipD |

Thailand and Australia |

63–75 |

61–64 |

[41] |

|

Immunoblot |

Glutathione S-transferases-BipD (GST–BipD) BipD |

Thailand |

78

100 |

90

91.1 |

[45] |

|

Immunoblot |

GST–BipD |

ND a |

ND |

ND |

[26] |

|

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) |

BipD |

Thailand |

100 |

100 |

[44] |

a ND: not determined.

7. Conclusions

Melioidosis is a severe bacterial infection caused by B. pseudomallei. Rapid antimicrobial therapy is needed to improve patient outcomes, which highlights the need for antigen detection for the rapid determination of B. pseudomallei in clinical samples. Hence, we reviewed information about BipD, a needle tip protein secreted by Bsa. As outlined in this review, BipD consists of abundant α-helices and some β-strands, and it exists as a dimer under biological conditions. It has principal roles in pathogenesis, such as facilitating the invasion of non-phagocytic cells, escape from the phagosome, the induction of intracellular replication, and the formation of actin tails. Several attempts have been made to detect BipD-specific antibodies from human sera using ELISA, immunoblotting, and SPR; however, none have been accepted for detecting B. pseudomallei in clinical samples. Therefore, we suggest that BipD be used in antigen-detection assays to directly indicate the presence of B. pseudomallei.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms9040711

References

- Sprague, L.; Neubauer, H. Melioidosis in animals: A review on epizootiology, diagnosis and clinical presentation. J. Vet. Med. Ser. B 2004, 51, 305–320.

- Limmathurotsakul, D.; Wongratanacheewin, S.; Teerawattanasook, N.; Wongsuvan, G.; Chaisuksant, S.; Chetchotisakd, P.; Chaowagul, W.; Day, N.P.; Peacock, S.J. Increasing incidence of human melioidosis in Northeast Thailand. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 82, 1113–1117.

- Stewart, T.; Engelthaler, D.M.; Blaney, D.D.; Tuanyok, A.; Wangsness, E.; Smith, T.L.; Pearson, T.; Komatsu, K.K.; Keim, P.; Currie, B.J. Epidemiology and investigation of melioidosis, Southern Arizona. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1286.

- Le Tohic, S.; Montana, M.; Koch, L.; Curti, C.; Vanelle, P. A review of melioidosis cases imported into Europe. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 1395–1408.

- Limmathurotsakul, D.; Golding, N.; Dance, D.A.; Messina, J.P.; Pigott, D.M.; Moyes, C.L.; Rolim, D.B.; Bertherat, E.; Day, N.P.; Peacock, S.J. Predicted global distribution of Burkholderia pseudomallei and burden of melioidosis. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 15008.

- Nathan, S.; Chieng, S.; Kingsley, P.V.; Mohan, A.; Podin, Y.; Ooi, M.-H.; Mariappan, V.; Vellasamy, K.M.; Vadivelu, J.; Daim, S. Melioidosis in Malaysia: Incidence, clinical challenges, and advances in understanding pathogenesis. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2018, 3, 25.

- Wiersinga, W.J.; Van der Poll, T.; White, N.J.; Day, N.P.; Peacock, S.J. Melioidosis: Insights into the pathogenicity of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 272–282.

- Tellapragada, C.; Shaw, T.; D’Souza, A.; Eshwara, V.K.; Mukhopadhyay, C. Improved detection of Burkholderia pseudomallei from non-blood clinical specimens using enrichment culture and PCR: Narrowing diagnostic gap in resource-constrained settings. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2017, 22, 866–870.

- Premaratne, K.; Karunaratne, G.; Dias, R.; Lamahewage, A.; Samarasinghe, M.; Corea, E.; Gunawardena, R. Melioidosis presenting as parotid abscess in children: Two consecutive cases. Sri Lankan J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 7, 116–122.

- Chen, P.; Gates-Hollingsworth, M.; Pandit, S.; Park, A.; Montgomery, D.; AuCoin, D.; Gu, J.; Zenhausern, F. based Vertical Flow Immunoassay (VFI) for detection of bio-threat pathogens. Talanta 2019, 191, 81–88.

- Woods, K.L.; Boutthasavong, L.; NicFhogartaigh, C.; Lee, S.J.; Davong, V.; AuCoin, D.P.; Dance, D.A. Evaluation of a rapid diagnostic test for detection of Burkholderia pseudomallei in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56.

- Pumpuang, A.; Dunachie, S.J.; Phokrai, P.; Jenjaroen, K.; Sintiprungrat, K.; Boonsilp, S.; Brett, P.J.; Burtnick, M.N.; Chantratita, N. Comparison of O-polysaccharide and hemolysin co-regulated protein as target antigens for serodiagnosis of melioidosis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005499.

- Chaichana, P.; Jenjaroen, K.; Amornchai, P.; Chumseng, S.; Langla, S.; Rongkard, P.; Sumonwiriya, M.; Jeeyapant, A.; Chantratita, N.; Teparrukkul, P. Antibodies in melioidosis: The role of the indirect hemagglutination assay in evaluating patients and exposed populations. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 99, 1378–1385.

- Kohler, C.; Dunachie, S.J.; Müller, E.; Kohler, A.; Jenjaroen, K.; Teparrukkul, P.; Baier, V.; Ehricht, R.; Steinmetz, I. Rapid and sensitive multiplex detection of Burkholderia pseudomallei-specific antibodies in melioidosis patients based on a protein microarray approach. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004847.

- Dulsuk, A.; Paksanont, S.; Sangchankoom, A.; Ekchariyawat, P.; Phunpang, R.; Jutrakul, Y.; Chantratita, N.; West, T.E. Validation of a monoclonal antibody-based immunofluorescent assay to detect Burkholderia pseudomallei in blood cultures. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 110, 670–672.

- Peeters, M.; Chung, P.; Lin, H.; Mortelmans, K.; Phe, C.; San, C.; Kuijpers, L.M.F.; Teav, S.; Phe, T.; Jacobs, J. Diagnostic accuracy of the InBiOS AMD rapid diagnostic test for the detection of Burkholderia pseudomallei antigen in grown blood culture broth. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 37, 1169–1177.

- Barua, A.; Sathyaseelan, K. Identification of New PCR Targets and its Validation for Development. Def. Life. Sci. J. 2016, 1, 18.

- Lowe, C.-W.; Satterfield, B.A.; Nelson, D.B.; Thiriot, J.D.; Heder, M.J.; March, J.K.; Drake, D.S.; Lew, C.S.; Bunnell, A.J.; Moore, E.S. A Quadruplex Real-Time PCR Assay for the Rapid Detection and Differentiation of the Most Relevant Members of the B. pseudomallei Complex: B. mallei, B. pseudomallei, and B. thailandensis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164006.

- Sangwichian, O.; Whistler, T.; Nithichanon, A.; Kewcharoenwong, C.; Sein, M.M.; Arayanuphum, C.; Chantratita, N.; Lertmemongkolchai, G. Adapting microarray gene expression signatures for early melioidosis diagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020.

- Rizzi, M.C.; Rattanavong, S.; Bouthasavong, L.; Seubsanith, A.; Vongsouvath, M.; Davong, V.; De Silvestri, A.; Manciulli, T.; Newton, P.N.; Dance, D.A. Evaluation of the Active Melioidosis Detect™ test as a point-of-care tool for the early diagnosis of melioidosis: A comparison with culture in Laos. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 113, 757–763.

- Suttisunhakul, V.; Wuthiekanun, V.; Brett, P.J.; Khusmith, S.; Day, N.P.; Burtnick, M.N.; Limmathurotsakul, D.; Chantratita, N. Development of rapid enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for detection of antibodies to Burkholderia pseudomallei. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 1259–1268.

- Felgner, P.L.; Kayala, M.A.; Vigil, A.; Burk, C.; Nakajima-Sasaki, R.; Pablo, J.; Molina, D.M.; Hirst, S.; Chew, J.S.; Wang, D. A Burkholderia pseudomallei protein microarray reveals serodiagnostic and cross-reactive antigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 13499–13504.

- Kritsiriwuthinan, K.; Wajanarogana, S.; Choosang, K.; Homsian, J.; Rerkthanom, S. Production and evaluation of recombinant Burkholderia pseudomallei GroEL and OmpA proteins for serodiagnosis of melioidosis. Acta Trop. 2018, 178, 333–339.

- Abby, S.S.; Rocha, E.P. The non-flagellar type III secretion system evolved from the bacterial flagellum and diversified into host-cell adapted systems. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002983.

- Holden, M.T.; Titball, R.W.; Peacock, S.J.; Cerdeño-Tárraga, A.M.; Atkins, T.; Crossman, L.C.; Pitt, T.; Churcher, C.; Mungall, K.; Bentley, S.D. Genomic plasticity of the causative agent of melioidosis, Burkholderia pseudomallei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 14240–14245.

- Stevens, M.P.; Wood, M.W.; Taylor, L.A.; Monaghan, P.; Hawes, P.; Jones, P.W.; Wallis, T.S.; Galyov, E.E. An Inv/Mxi-Spa-like type III protein secretion system in Burkholderia pseudomallei modulates intracellular behaviour of the pathogen. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 46, 649–659.

- Zilkenat, S.; Franz-Wachtel, M.; Stierhof, Y.-D.; Galán, J.E.; Macek, B.; Wagner, S. Determination of the stoichiometry of the complete bacterial type III secretion needle complex using a combined quantitative proteomic approach. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2016, 15, 1598–1609.

- Vander Broek, C.W.; Stevens, J.M. Type III secretion in the melioidosis pathogen Burkholderia pseudomallei. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 255.

- Bajunaid, W.; Haidar-Ahmad, N.; Kottarampatel, A.H.; Ourida Manigat, F.; Silué, N.F.; Tchagang, C.; Tomaro, K.; Campbell-Valois, F.-X. The T3SS of Shigella: Expression, Structure, Function, and Role in Vacuole Escape. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1933.

- Erskine, P.; Knight, M.; Ruaux, A.; Mikolajek, H.; Sang, N.W.F.; Withers, J.; Gill, R.; Wood, S.; Wood, M.; Fox, G. High resolution structure of BipD: An invasion protein associated with the type III secretion system of Burkholderia pseudomallei. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 363, 125–136.

- Knight, M.; Ruaux, A.; Mikolajek, H.; Erskine, P.; Gill, R.; Wood, S.; Wood, M.; Cooper, J. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of BipD, a virulence factor from Burkholderia pseudomallei. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F. Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2006, 62, 761–764.

- Pal, M.; Erskine, P.; Gill, R.; Wood, S.; Cooper, J. Near-atomic resolution analysis of BipD, a component of the type III secretion system of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F. Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2010, 66, 990–993.

- Moule, M.G.; Spink, N.; Willcocks, S.; Lim, J.; Guerra-Assunção, J.A.; Cia, F.; Champion, O.L.; Senior, N.J.; Atkins, H.S.; Clark, T. Characterization of new virulence factors involved in the intracellular growth and survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 701–710.

- Kespichayawattana, W.; Rattanachetkul, S.; Wanun, T.; Utaisincharoen, P.; Sirisinha, S. Burkholderia pseudomallei induces cell fusion and actin-associated membrane protrusion: A possible mechanism for cell-to-cell spreading. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 5377–5384.

- Stockton, J.L.; Torres, A.G. Multinucleated Giant Cell Formation as a Portal to Chronic Bacterial Infections. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1637.

- Gong, L.; Cullinane, M.; Treerat, P.; Ramm, G.; Prescott, M.; Adler, B.; Boyce, J.D.; Devenish, R.J. The Burkholderia pseudomallei type III secretion system and BopA are required for evasion of LC3-associated phagocytosis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17852.

- Burtnick, M.N.; Brett, P.J.; Nair, V.; Warawa, J.M.; Woods, D.E.; Gherardini, F.C. Burkholderia pseudomallei type III secretion system mutants exhibit delayed vacuolar escape phenotypes in RAW 264.7 murine macrophages. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 2991–3000.

- Stevens, M.P.; Friebel, A.; Taylor, L.A.; Wood, M.W.; Brown, P.J.; Hardt, W.-D.; Galyov, E.E. A Burkholderia pseudomallei type III secreted protein, BopE, facilitates bacterial invasion of epithelial cells and exhibits guanine nucleotide exchange factor activity. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 4992–4996.

- Stevens, M.P.; Haque, A.; Atkins, T.; Hill, J.; Wood, M.W.; Easton, A.; Nelson, M.; Underwood-Fowler, C.; Titball, R.W.; Bancroft, G.J. Attenuated virulence and protective efficacy of a Burkholderia pseudomallei bsa type III secretion mutant in murine models of melioidosis. Microbiology 2004, 150, 2669–2676.

- Allwood, E.M.; Logue, C.-A.; Hafner, G.J.; Ketheesan, N.; Norton, R.E.; Peak, I.R.; Beacham, I.R. Evaluation of recombinant antigens for diagnosis of melioidosis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2008, 54, 144–153.

- Druar, C.; Yu, F.; Barnes, J.L.; Okinaka, R.T.; Chantratita, N.; Beg, S.; Stratilo, C.W.; Olive, A.J.; Soltes, G.; Russell, M.L. Evaluating Burkholderia pseudomallei Bip proteins as vaccines and Bip antibodies as detection agents. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2008, 52, 78–87.

- Chuah, S.C.; Gilmore, G.; Norton, R.E. Rapid serological diagnosis of melioidosis: An evaluation of a prototype immunochromatographic test. Pathology 2005, 37, 169–171.

- Castillo, J.; Gáspár, S.; Leth, S.; Niculescu, M.; Mortari, A.; Bontidean, I.; Soukharev, V.; Dorneanu, S.; Ryabov, A.; Csöregi, E. Biosensors for life quality: Design, development and applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2004, 102, 179–194.

- Dawan, S.; Kanatharana, P.; Chotigeat, W.; Jitsurong, S.; Thavarungkul, P. Surface plasmon resonance immunosensor for rapid and specific diagnosis of melioidosis antibody. Southeast. Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2011, 42, 1168.

- Visutthi, M.; Jitsurong, S.; Chotigeat, W. Production and purification of Burkholderia pseudomallei BipD protein. Southeast. Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2008, 39, 109.