Natural biophenols are a wide group of molecules (over 8000 described so far) found only in the plant kingdom; their molecules display one or more aromatic rings carrying one or more hydroxyl groups; these molecules display remarkable antioxidant power and are produced as secondary metabolites by the plant for protection against the attack by bacteria, fungi, and insects (phytoalexins). Plant polyphenols include non-flavonoids or flavonoids; the latter are further divided into flavonols, flavononols, flavones, anthocyanins, procyanidins, phenolic acids, stilbenes, and tannins depending on the number of hydroxyls in the molecule and on the nature and the position of other substituents.

- plant polyphenols

- hormesis

- autophagy

- Mediterranean diet

- olive oil

- curcumin

- resveratrol

- oleuropein

- hydroxytyrosol

- epigallocathechin

- epigenetics

1. Polyphenols: Important Players of the Mediterranean/Asian Diets

Natural biophenols are a wide group of molecules (over 8000 described so far) found only in the plant kingdom; their molecules display one or more aromatic rings carrying one or more hydroxyl groups; these molecules display remarkable antioxidant power and are produced as secondary metabolites by the plant for protection against the attack by bacteria, fungi, and insects (phytoalexins) [1]. Plant polyphenols include non-flavonoids or flavonoids; the latter are further divided into flavonols, flavononols, flavones, anthocyanins, procyanidins, phenolic acids, stilbenes, and tannins depending on the number of hydroxyls in the molecule and on the nature and the position of other substituents [2]. The natural phenols most studied for their healthy properties ar curcumin, a phenolic acid found in the rhizome of Curcuma longa Linn (family Zingiberaceae) and a component of the curry; epigallocathechins, notably epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), the flavanol found in green tea; resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene), a stilbene found in grapes and in red wine; quercetin and myricetin, flavonols present in tea, onions, cocoa, red wine, and in Ginkgo biloba extracts. Many other plant phenols or their metabolic derivatives have also been investigated, yet with variable results; these include tannic, ellagic, ferulic, nordihydroguaiaretic and caffeic acid, morin, rutin, apigenin, baicalein, kaempferol, fisetin, luteolin, rottlerin, malvidin, piceatannol, and silibinin.

More recently, particular interest has been dedicated to the polyphenols present abundantly in the leaves and in the ripening fruits of the olive tree (Olea europaea); including flavonols, lignans iridoids, and their glycosides. Iridoids are monoterpenes containing a cyclopentane ring fused to a six-atom heterocycle with an oxygen atom, whereas the molecules where the cyclopentane ring is interrupted are indicated as secoiridoids. The most abundant polyphenols found in the EVOO include the secoiridoids oleuropein and ligstroside, both in the glycated and in the aglycone forms, and their main metabolites: The phenolic alcohols tyrosol (p-hydroxyphenylethanol, p-HPEA) and hydroxytyrosol (3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol, 3,4-DHPEA), oleacein, and oleocanthal. Oleuropein confers the bitter taste to the olive leaves, drupes, and EVOO, whereas oleocanthal produces the burning sensation in the back of the throat when consuming EVOO [3][4]. Phenolic concentration in plants depends on several variables; in the olive tree, and hence in the EVOO, these include (i) olive cultivar and stage of ripening [5]; (ii) environmental cues (altitude, cultivation practices, meteorological factors, and irrigation); (iii) technological aspects such as extraction conditions (temperature and others) and systems to separate oil from olive pastes; and (iv) storage conditions and time, due to spontaneous oxidation, and deposition of suspended water droplets with their content of polyphenols [6]. At the best, polyphenol content in the EVOO can exceed 60 mg/100 g.

Plant polyphenols have been considered for their remarkable antioxidant properties; however, their effects go well beyond this property. In fact, plant polyphenols have been shown to possess beneficial effects against aggregation of peptides/proteins into amyloid assemblies, a process involved in several amyloid diseases, particularly T2DM, AD, and PD, thus reducing the load of intra- or extracellular deposits [1]. T2DM is characterized by aggregates of the peptide amylin in insulin-secreting pancreatic β-cells; AD results from the extracellular amyloid aggregation of the Aβ peptide (mostly Aβ1–42) in senile and neuritic plaques and the intracellular aggregation into neurofibrillary tangles of tau protein; these aggregates are found in specific brain areas, notably the hippocampus and the pre-frontal cortex. PD results mostly from the aggregation of α-synuclein into intracellular Lewy bodies found in the neurons of the mesencephalic substantia nigra. Actually, olive polyphenols, notably OLE and its main metabolite, HT, have been reported to be effective against amyloid aggregation and the ensuing pathologic effects in T2DM [7][8], AD [9][10][11][12][13][14][15] and, possibly, in PD [16][17] and other amyloidoses. Plant polyphenols, including those enriched in EVOO, have also been reported to reduce insulin resistance and to improve impaired glucose homeostasis, two main signs of T2DM. Considering that increasing evidence supports a strong link between diabetes (mainly T2DM) and neurodegeneration associated with AD [18][19], it is conceivable that many plant polyphenols can interfere with both pathologies at similar molecular levels.

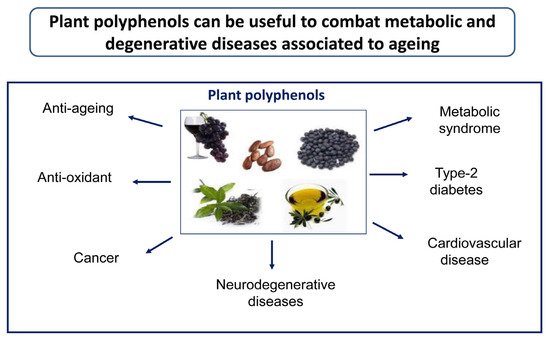

The beneficial effects of plant preparations and derivatives, including, in the case of olive, oil and leaf extracts, have already been known for the last couple of centuries and have been scientifically investigated over the recent several decades; these researches have progressively led to a focus on the multi-target activity and health properties of plant polyphenols, including the anti-amyloid aggregation, antioxidant, antimicrobial, antihypertensive, hypoglycemic, and vasodilator effects. The antioxidant power has been shown to involve modulation of oxidative pathways [20], direct action on enzymes, proteins, receptors, and several types of signaling paths [21][22], as well as the interference with epigenetic modifications of chromatin [23] (see below). The clinical significance of the beneficial properties of plant polyphenols was first reported in 1950 [24], leading to the inclusion in the European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.) of the 80% alcoholic extract of olive leaves, containing oleuropein, HT, caffeic acid, tyrosol, apigenin, and verbascoside [25][26]. Biophenols can also be used to develop new drugs useful to combat chronic inflammatory conditions, the risk of thrombosis, CVD-related states such as atherosclerosis [27], cancer [28], also in combination with anti-cancer drugs [29], as well as to reduce amyloid deposition associated with T2DM and aging-related states such as neurodegeneration [1][30] (Figure 1). Finally, the molecular scaffolds of plant polyphenols are also investigated to develop new molecules potentially exploitable in disease prevention and therapy [31].

Figure 1. Plant polyphenols can be useful to prevent/combat a number of lifestyle-, metabolic-, and aging-associated pathologies.

The beneficial effects of olive and other plant polyphenols can be hindered by the reduced bioavailability of the latter following reduced intestinal absorption and their rapid biotransformation in the organism; in addition, chemical modifications of many polyphenols by gut microbiota further reduces their bioavailability and biological efficacy [32]. Several strategies to overcome reduced bioavailability have been proposed, including encapsulation within nanoparticles [33], self-microemulsifying formulations [34], and others (reviewed in [35]). Yet, several studies have shown that many plant polyphenols, including EVOO polyphenols, are absorbed, although in reduced amount, by humans and distributed, in part, to organs and tissues before completion of their secondary metabolism, degradation, and excretion [36][37][38]. Moreover, some OLE metabolites, notably HT, arising mainly from acid hydrolysis in the stomach, have been found in the brain of TgCRND8 mice and rats after an acute oral administration of either OLE or HT, which supports the ability of OLE and some of its derivatives, including HT, to cross the blood–brain barrier [39][40]. In particular, convincing evidence indicates that HT is dose-dependently bioavailable; it is substantially (40%) absorbed and reaches maximum concentration in plasma after 5–30 min from EVOO ingestion, with a calculated total bioavailability around 10% due to metabolic modifications in the gut and in the organism through phase II conjugation reactions [41]. Thus, in spite of reduced information on many aspects of their pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and metabolic modifications by gut microbiota and in the organism, oral assumption of plant polyphenols results in partial absorption and distribution to the whole organism (reviewed in [42]).

2. Plant Polyphenols Rescue Altered Homeostatic Systems in Cells

2.1. Redox Homeostasis and the Inflammatory Response

Emerging research has recently focused on biological relevance for cell protection in many degenerative diseases and for neuroprotection in several neurodegenerative disorders, particularly AD and PD, of the redox homeostasis elicited by plant polyphenols through the activation of vitagene signaling pathways. The latter involves redox sensitive genes such as the Hsp70, heme-oxygenase-1 (HO-1), thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase, and sirtuins system [43]. All these cytoprotective genes can be transcriptionally modulated by the nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2) as a part of the electrophile counterattack, defined phase 2 response. Nrf2 is a key transcription effector for the activation of wide range of cytoprotective genes (>500). The Nrf2 activity induces a mild stress response, providing a healthy physiological steady state and extending lifespan in different cells and animal models. On the other hand, a chronic long-term Nrf2 stimulation may lead to pathophysiological events, therefore the Nrf2 signaling can be considered as a hormetic-like pathway [44][45]. Increasing evidences show that plant polyphenols activate the phase 2 response leading to the expression of various Nrf2-dependent antioxidant vitagenes. These effects represent a powerful instrument supporting redox homeostasis under stressful conditions [46] and support the assumptions that the helpful properties of polyphenols carry out through adaptive stress response vitagenes. Within this context, both heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and Hsp70 have received considerable attention for their recognized antioxidative function needed to maintain cell homeostasis [47]. Moreover, the well-known principle of hormesis may be applied also to HO-1. In fact, although several studies have shown the crucial role of HO-1 activity against oxidative and nitrosative stress [48][49], excessive upregulation of HO-1 system may be deleterious for cells, because of accumulation of its by-products such as carbon monoxide (CO), iron, and the bilirubin precursor, biliverdin [50]; in light of the concept of hormesis, it is reasonable to look at these by-products of HO1 activity in terms of their positive effects obtained at very low concentrations.

As reported by Naviaux and coworkers [51], the hormetic response is activated when chemical-physical or biological hazards surpass the cellular capacity for homeostasis. The ensuing disruption of homeostasis induces a cascade of deleterious molecular changes in cells involving electron flow, oxygen consumption, and redox potential, that result in alterations of cellular structures and processes, including membrane fluidity, bioenergetics, protein folding, and misfolding. An increasing body of evidence shows that most chronic diseases arise from the biological response to a stress factor, not from the initial injury, or from the agent of the injury itself. The initial components of this cascade elicit the release of ATP, ADP, metabolic intermediates of Krebs cycle, oxygen, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) that is sustained by purinergic signaling pathway [51]. The anti-inflammatory and resilience phenotypes arise from these initial adaptive processes eventually mediate protection from a variety of potential injuries.

Dietary plant polyphenols that act as powerful antioxidants may block/abolish the anti-inflammatory phenotype that results from a redox regulatory signaling pathway [52][53][54][55]. More recent findings suggest that the biphasic dose responses of hormetic type are common effects of plant polyphenols. Interestingly, plant polyphenols are considered as a “preventive treatment of disease” inducing biological effects with important therapeutic applications to in vitro and in vivo models through the activation of adaptive responses [56]. Currently, increasing evidence suggests that plant polyphenols such as curcumin, sulforaphane, resveratrol, HT, and OLE may offer beneficial effects acting in a hormetic-like manner by activating adaptive stress-response pathways and making the hormesis concept fully applicable to the field of nutrition. Moreover, it has been considered that plant polyphenols may be protective through hormetic processes that involve the stress-activated “vitagenes” [52][57].

Chronic neuroinflammation is a prominent feature shared by several neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD and PD. Microglial activation, the hallmark of brain neuroinflammation, results in the production of highly pro-inflammatory cytokines (i.e., TNF-α, IL-β, prostaglandin E2, cyclooxygenases, and iNOS through the modulation of signal transduction pathways), ROS, and NO, leading to cellular modifications including mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired energy metabolism, altered redox homeostasis, lipid peroxidation, DNA fragmentation, neuronal inflammation, and cell death; recently, these alterations have been associated with the pathogenesis of neurological disorders [58][59]. Inflammasomes are multiprotein signaling complexes that regulate cells of the innate immune system, mainly microglial cells in the brain. Notably, a considerable amount of information has provided evidence on the existence of inflammasome-mediated inflammatory pathways in neurological diseases. In particular, the NLR family, pyrin domain-containing-3 (NLRP3) inflammasome has been shown to play a pathogenic role in the development of neuroinflammatory disorders, such as AD [60] and PD [61].

In vivo and in vitro studies have highlighted a direct relationship between inflammasome activation and AD pathogenesis, suggesting that inflammasome inhibition represents a potential therapeutic approach for AD treatment. This concept was confirmed in APP/PS1mice (transgenic mice with chronic deposition of Aβ) where a deficiency of NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1 activity were found [62]. Moreover, in these mice models, the production of microglia with phenotype M2 induced by NLRP3 inflammasome deficiency was observed, resulting in reduced deposition of Aβ [62]. In addition, in humans, enhanced caspase-1 activation was found mainly in the hippocampal area of human brain tissue of patients with AD, [62]. Moreover, in an AD mouse model, administration of cathepsin-B (produced by microglia after Aβ phagocytosis) inhibitors significantly decreased the load of amyloid plaques in the mouse brain tissue and resulted in substantial improvement in memory deficit. In PD patient brains, the inflammasome pathway can potentially be activated by oxidative stress and by insoluble α-synuclein aggregates [63]. The pathophysiological link between inflammasome responses and Aβ-plaque spreading indicates that pharmacological targeting of inflammasomes may represent a novel, potential treatment strategy for AD and PD.

In light of the data reported above, the activities of plant polyphenols against neuroinflammation appear to target activated microglia resulting in low-level production of pro-inflammatory molecules induced by the NRLP3 inflammasome. In particular, many recent data suggest the key role played by phenolic components of EVOO in counteracting protein misfolding and proteotoxicity, with a particular emphasis on the mechanisms leading to the onset and progression of AD and PD, including APP processing, Aβ peptide and tau amyloid aggregation, autophagy impairment, disruption of redox homeostasis, α-synuclein neurotoxicity, and neuroinflammation [64][65]. Additionally, several data indicate that OLE interferes with APP processing [66] and with the amyloid aggregation of Aβ and tau protein, escaping the growth of toxic Aβ oligomers both in vitro [13][15][67][68], in C. elegans [69], and in TgCRND8 mice, a transgenic model of Aβ deposition [39]. In accordance with these data, a recent study has reported that rats fed with OLE display significant improvement of cognitive performance; in fact, OLE diet decreases the apoptosis and oxidative stress levels and prevents the impairment of spatial learning and memory resulting from morphine-induced neurotoxicity to the hippocampus [70].

It is noteworthy that HT, a dopamine metabolite, is present in the brain [71]. Monoamine oxidase (MAO) catalyzes oxidative deamination of dopamine in a toxic metabolite, DOPAL (3,4-dihydroxyphenylaldehyde), that can be oxidized by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) to DOPAC (3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid), the major metabolite of dopamine in the brainor may be reduced to HT by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). At the same time, DOPAC reductase can transform DOPAC in HT [72]. DOPAL is a highly reactive metabolite, suggesting that it might be a neurotoxic dopamine metabolite with a role in the pathogenesis of PD [73][74].

HT removes soluble oligomeric Aβ1–42 plus ibotenic acid-induced neurobehavioral dysfunction following intracerebroventricular injection of Aβ1–42 [67]. In hippocampal neurons, HT treatment rescues, to a significant extent, negatively altered spatial reference and working memory induced by Aβ, an effect associated with reduced activation of death kinases such as JNK and p38-MAPK, while concomitantly increasing the survival-signaling pathways such as ERK-MAPK/RSK2, PI3K/Akt1, and JAK2/STAT3 [67].

In human trials, a higher adherence to the MD was associated with reduced cognitive decline and the risk of AD [75]. In transgenic AD mice, the positive effects of EVOO in preventing and delaying the onset of AD and declining the severity of its symptoms have been reported [76]. However, in spite of the reported biological effects, it has not been clear how efficiently HT acts against AD progression. Six-month HT administration to three-month-old female transgenic APP/PS1 mice at 5 mg/kg/day improved the electroencephalographic activity and cognitive function and reduced mitochondrial oxidative stress and neuroinflammation [77]. Moreover, HT was shown to dose-dependently inhibit toxicity of α-synuclein aggregation in PD [78] and HT and OLE improved spatial working memory and energetic metabolism in the brain of aged mice [79]. Notably, HT efficiently neutralizes free radicals and protects biomolecules from ROS-induced oxidative damage. In this regard, HT activates the Nrf2–antioxidant response element (ARE) pathway, leading to the activation of phase II detoxifying enzymes and the protection of dopaminergic neurons exposed to hydrogen peroxide or to 6-hydroxydopamine [16][80]. In addition, HT improved mitochondrial function and induced phase II antioxidative enzymes, which decreased oxidative stress in the brain of db/db mice [81]. Recently, it has also been shown that OLE improves mitochondrial performance through activation of the Nrf2-mediated signaling pathway protecting the hypothalamus from oxidative stress [82]. In conclusion, HT is being considered with interest for possible use in pharmacological mitigation of neurodegenerative processes as a potent antioxidant and a novel small molecule that can upregulate the Nrf2-ARE pathway.

Interestingly, plant polyphenols upregulate the vitagene signaling pathway that represents a potential therapeutic target in the crosstalk of inflammatory response process and oxidative stress in neurodegeneration. Accordingly, recent in vitro and in vivo studies have indicated that HT attenuates the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway by reducing pro-inflammatory interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 cytokine levels, oxidative stress, neuronal apoptosis, via activation of the Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling pathway and suppression of NF-κB [83][84][85]. Previous research revealed that HT and OLE activate the signaling pathway from Sirt1, an important member of the vitagene family that catalyzes the deacetylation of various substrates, by utilizing nicotinamide (NAD+) as a substrate, to restore adaptive homeostasis under stress conditions [86]. By regulating cellular redox homeostasis, Sirt1 plays a critical role in neuron survival, insulin sensitivity, mitochondrial biogenesis, neurogenesis, and inflammation [49]. Sirt1 has been shown to be essential for synaptic plasticity, cognitive functions [87], modulation of learning, and the preservation of memory processes that deteriorate during aging, in the brain [88]. Recently, in vitro and in vivo studies suggest that HT and OLE inhibit the inflammatory response through different pathways regulated by several members of the sirtuin family (e.g., Sirt1, Sirt2, Sirt6) [77][89][90][91][92][93].

The thioredoxin system (Trx/TrxR) is a meaningful thiol/disulphide redox controller ensuring the cellular redox homeostasis [94][95]. In addition to the regulation of the expression of the encoding genes, TrxR activity is also regulated post-translationally by the thioredoxin inhibitory protein (TxNIP). In this context, a recent study has reported that HT induces neuroprotection and cellular antioxidant defenses via upregulation of the Keap1-Nrf2-TRXR1 pathway [96]. Sulforaphane is an herbal isothiocyanate enriched in cruciferous vegetables obtained in high concentrations from broccoli seeds and sprouts; myrosinase, an enzyme segregated in plant cells and released when the latter are masticated and ingested, produces sulphoraphane by glucoraphanin hydrolysis. This molecule has been shown to be active by fostering cellular defenses against a broad spectrum of cellular stresses. Evidence has shown that sulforaphane in the CNS activates Hsps and related mechanisms central to multiple cellular processes, including synaptic transmission, and improves cortical connectivity [97]. In addition, sulforaphane can also decrease STAT-1 and NLRP3 inflammasome activation by the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway in human microglia-like THP-1 cells [98]. Finally, a recent in vivo study showed that sulforaphane modulates Hsp70 upregulating C-terminus of Hsp70-interacting protein (CHIP) and has the potential to reduce the deposition of Aβ and tau in a mouse models of AD [99].

Several studies have reported the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of resveratrol, presently under clinical trial against neurodegenerative disorders. Recent compelling evidence indicated that resveratrol at micromolar concentrations can effectively scavenge free radicals and is an importantallosteric activator of the vitagene signaling pathway. In addition, resveratrol is involved in the neuroprotective mechanisms by increasing the Nrf2 pathway and reducing NF-κB activity, and therefore exerts a positive effect against a neuroinflammatory state and counteracts the progression of brain aging [100]. Some studies have also shown that resveratrol improves the learning and memory deficit in neurodegenerative disorders and, through its antioxidant activity, protects against memory decline in AD [101]. One of the major mechanisms of resveratrol as neuroprotective molecule is the activation of Sirt1 that is expressed in the adult mammalian brain, predominantly in neurons [102]. Moreover, resveratrol upregulates the Sirt1 pathway, thus preventing Aβ-induced microglial death and contributing to improve cognitive function [103] and induces the SIRT-1 and TRX signaling pathways with reduction of Aβ-stimulated NF-κB signaling, that contributes to its strong neuroprotection in AD [104][105][106][107].

Some preclinical studies have also suggested a positive role of curcumin as an adjuvant therapeutic strategy in free radical-based disorders, particularly neurodegenerative disorders. Some studies have reported the key role played by HO-1 as a target for neuroprotection by curcumin [52][108]. Several studies showed that resveratrol and curcumin increase HO-1 expression in PC12 cells and endothelial cells, among other cell lines [105][107][109]. Moreover, it has been suggested that curcumin inhibits IL-1β secretion and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages, reduces soluble tau oligomers, and improves cognition by increasing HSP70, HSP90, and HSC70, in aged human tau transgenic mice [110][111].

Taken together, all these data indicate that the activation of stress responsive mechanisms following moderate and chronic consumption of low doses of plant polyphenols induces the vitagene signaling pathway, thus activating antioxidant and neuroprotective cascades that could be effective to prevent neuroinflammation in aging-associated cognitive decline, and thereby improves health-life and longevity in animals and humans (Table 2).

Table 2. Polyphenols activity in cellular protective pathways. Activated pathways: ↑; Inactivated pathways: ↓.

| Polyphenols | Anti-Oxidant | Anti-Inflammatory | Anti-Aggregation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oleuropein Aglycone | ↑Sirt1 ↑Nrf2 |

↑Sirt1, Sirt2, Sirt6 | Aβ, Tau, α-Syn |

| Hydroxytyrosol | ↑Sirt1 ↑Nrf-2/HO-1 ↑Nrf-2-ARE ↑Keap1-Nrf2-TRXR1 |

↑Sirt1, Sirt2, Sirt6 ↓NLRP3 inflammasome ↓IL-1β, IL-18 |

α-Syn Aβ |

| Sulforaphane | ↑Hsp70-CHIP | ↓NLRP3 inflammasome ↓STAT1 |

|

| Resveratrol | ↑Nrf-2/HO-1 ↑TRX ↓Nf-κB |

↑Sirt1 | Aβ, Tau |

| Curcumin | ↑HO-1 ↑Hsp70 ↑Hsp90 ↑Hsc70 |

↓IL-1β ↓NLRP3 |

Aβ, Tau |

2.2. Metabolic Homeostasis

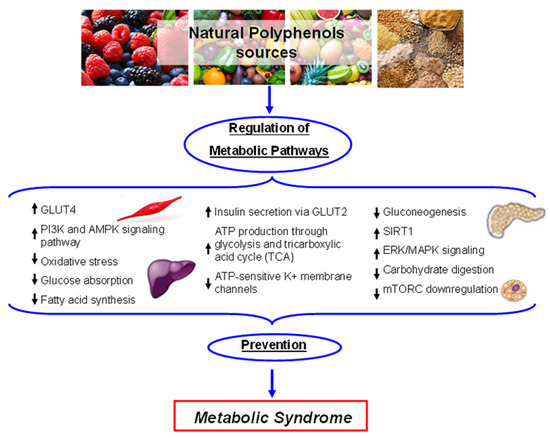

Traditionally, the main aim of nutrition is to provide correct amounts of dietary principles to prevent and, when needed, to treat, nutritional deficiencies. However, when nutrition is inadequate or excessive, the body faces the problem of controlling the amount of nutrients absorbed and stored, with the ensuing emergence of diet-associated pathologies, including MetS. The latter is a complex of symptoms and pathological conditions appearing in people over 65, particularly in females [112], induced by insulin resistance; MetS includes T2DM, cardiovascular diseases, obesity, non-alcoholic liver steatosis, and cancer [113]. Growing evidence indicates a significant reduction of the incidence of T2DM and MetS by the intake of plant polyphenols [114], particularly those found in the EVOO [115][116]. MetS treatment include lifestyle modifications such as physical activity, weight control, and intake of plant food products, such as whole grains, berries, fruits, and vegetables, all known to be sources of many polyphenols [117][118].

The regulation of blood glucose levels is dependent on the liver, in coordination with muscle and adipose tissue. Particularly, in the postprandial state, the liver involves several enzymes such as glucokinase and glycogen synthase to store glucose via the glycogenesis pathway. Moreover, the produced glucose by the liver, via glycogenolysis or gluconeogenesis pathways, depends by pyruvate carboxylase, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, and glucose-6-phosphatase activities [119]. In abnormal conditions, the increased post-prandial Apo-B48 levels correlate with the blood glucose levels and lipid profile [120], promoting and/or worsening the atherosclerotic process [121]. A correlation between oxidative stress and incidence of cardiovascular events was observed in diabetic vs. non-diabetic patients with post-prandial glycaemia [122]. Indeed, a recent study in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) reported a correlation between a high-fat meal and enhanced circulating levels of gut-derived bacteria lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [123]; this modification may represent an important activator step for systemic post-prandial oxidative stress as LPS is responsible for activation of Nox2, a most important ROS producer [124]; overall, data obtained in animal models and in human studies highlight the beneficial effects on postprandial blood glucose levels of natural polyphenols derived from food fractions and beverages. It has been observed that OLE and HT in diabetic rats modulate activities of hepatic antioxidant enzymes, superoxide dismutase, and catalase, attenuating the oxidative stress associated with diabetes [125]. Other data reported that EVOO consumption is associated with down-regulation of Nox-2-derived oxidative stress [126], indicating its ability to mitigate post-prandial oxidative stress via lowering post-prandial LPS also in patients with impaired fasting glucose [127]. Another study highlighted the different pattern of postprandial glycaemia induced by consumption of cranberry juice sweetened with high-fructose corn syrup with respect to comparable amount of a sweetener in water [128]. Finally, a very recent study carried out on stroke-affected mice fed with HT-supplemented diet showed a remarkable recovery of motor and cognitive functions, and of magnetic resonance imaging parameters, together with improvement in neuroinflammation and neurogenesis with respect to controls mice fed with normal diet [129].

Plant polyphenols influence glucose metabolism through several mechanisms such as reduction of intestine carbohydrate digestion and glucose absorption, stimulation of pancreatic β-cells to secret insulin, modulation of liver glucose release, activation of insulin-sensitive tissues in terms of insulin receptors, and glucose uptake. In this context, different polyphenols have been shown to inhibit the enzymes involved in digestion to glucose of dietary carbohydrates, α-amylase and α-glucosidase [118], reducing the rate of glucose release and absorption, thus suppressing post-prandial hyperglycemia [130][131]. The polyphenols for which these inhibitory effects have been reported include quercetin, myricetin, luteolin, EGCG theaflavin, and resveratrol [132][133][134]. Moreover, several flavonoids and phenolic acids, such as tannic acids, quercetin, and myricetin, have been reported to inhibit the sodium-dependent SGLT1 and the sodium-independent GLUT2 glucose transporters in cultured intestinal cells [135][136]. Furthermore, it has been reported that in vitro catechins of green tea [137], procyanidins derived from grape seed [138], bitter melon [139], phenols of EVOO [7], and black soybean [140] act on a GLUT4-mediated process to enhance insulin-mediated glucose uptake. Otherwise, data obtained from T2DM mice model demonstrated that black soybean seeds, rich in anthocyanins and procyanidins, reduced glucose levels and increased insulin sensitivity activating the PI3K and 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathways in the skeletal muscle and liver [141]. Moreover, AMPK activation was also observed in OLE-treated C2C12 cells and in high-fat-diet mice and resulted as being correlated with the up-regulation of GLUT4 in skeletal muscle and with the down-regulation of liver gluconeogenesis [142][143][144]. The increased GLUT4 expression induced by OLE treatment, particularly in association with insulin, reduced oxidative stress and enhanced glucose consumption, improving insulin sensitivity [145]. Differently, in pancreatic β-cells, the glucose-stimulated insulin secretion resulted from glucose entrance via GLUT2, glycolysis, and tricarboxylic acid cycle with increased ATP production and inactivation of ATP-sensitive K+ membrane channels [146]. Treatment with EGCG and buckwheat, the flavonoid rutin, resulted in reduced glucotoxicity to β-cells by activation of insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2) and AMPK signaling, and increased ATP levels [147][148]. Other data obtained with the RINmF5 cell model indicated that polyphenols such as quercetin, apigenin, and luteolin inhibit β-cell damage through suppression of NF-κB activity [149]. Moreover, the glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in β-cells was promoted by OLE treatment, but not its moiety HT, by activating ERK/MAPK signaling [150]. Other studies reported that HT reduces the oxidative stress in adipocytes, increasing the activity of AMPK, acetyl CoA carboxylase, hormone- sensitive lipase, and lipase phosphorylation, thus reducing the risk of obesity, a condition that correlates positively with the MetS [148][149] (Figure 4). Many of the reported metabolic and cellular physiologic effects elicited by plant polyphenols share a common upstream mechanism involving AMPK activation/mTORC inhibition. The serine/threonine kinases AMPK and mTORC are key co-ordinators and controllers of many molecular routines including those regulating cell metabolism (anabolism or catabolism) autophagy and proteostasis, cell proliferation, and the redox condition [149][151]. In turn, AMPK and mTORC activities are under control of several factors. AMPK, a regulator of cellular energy homeostasis [152], is triggered by energy stress signalled by reduced ATP and increased AMP levels [150]. AMPK is also activated by phosphorylation of two regulatory subunits by several kinases, including the energy stress-sensitive LKB [153], PKA [154], and the CAMM-GSK3β axis [155] as well as by other factors, including PPARα, associated with lipid metabolism [156] and hypoxia [157]. AMPK triggers the expression of antioxidant enzymes, notably HO-1, through Nrf2 [158][159], and improves the control of proteostasis [160] through direct activation of FOXO3 [161] and ULK1 [162] and by indirect activation of TFEB [163]; AMPK activation also improves both glucose metabolism by favoring GLUT4 translocation to the membrane [164][165] and lipid metabolism through PPARα. Finally, AMPK activation results in inhibition of mTORC following both direct phosphorylation and phosphorylation of the mTORC controller TSC [166].

Figure 4. Schematic representation of the main metabolic pathways influenced by plant polyphenols. Activated pathways: ↑; Inactivated pathways: ↓.

Some of the mechanisms reported above are also triggered by plant polyphenols. In particular, it has been reported that OLE increases intracellular free Ca2+ levels from the internal stores with ensuing activation of the calcium-CAMMK-GSK3β pathway [155] and reduces oxidative stress through AMPK-dependent activation of HO-1 [158], whereas in aged rats, resveratrol protects against high-fat diet-induced muscle atrophy counteracting PKA/LKB1/AMPK-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress [154]. Finally, plant polyphenols including quercetin, resveratrol, and catechins activate SIRT1, a class-3 histone deacetylase involved in several aging-related pathologies, including neurodegeneration [167]. Recent data with TgCRND1 mice indicate that SIRT1 is activated by OLE, with concomitant inhibition of PARP1 in a crosstalk affecting apoptosis and autophagy [39]. It is remarkable that some of these effects by several plant polyphenols are shared with the well-known antidiabetic drug metformin [168]. These molecules have different ways of accomplishing their functions and work in different cell types; however, taken together, the vast amount of research and preclinical data provide a convincing, yet still incomplete, explanation of the cellular protection by these substances that underlies their hormetic behaviour (see Figure 4).

2.3. Proteostasis

Proteostasis is a key biological process under strict cellular control by maintaining the equilibrium between protein synthesis and protein degradation by different protein degradation machineries (the chaperone–ubiquitin–proteasome and various forms of autophagy), whose homeostasis is needed for a healthy life span. The proteostasis network needs the coordinated action of both chaperones and the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS), and several types of autophagy, notably macro-autophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy. Molecular chaperones, in particular the heat shock proteins (HSPs), are the prime line of defense to counteract protein misfolding and the ensuing protein deposition; they recognize hydrophobic regions of proteins and promote either their refolding or their transfer to the UPS or autophagy systems [169]. The small HSPs are ATP-independent chaperones, a particular class of HSPs that bind misfolded and aggregation-prone proteins, avoiding undesired intermolecular interactions and preventing their aggregation with ensuing loss of function [170][171]. The UPS is localized both in the cytoplasm and in the nuclei; it provides rapid degradation of proteins following their polyubiquitination and subsequent delivery to the proteasome. The misfolded proteins of the secretory pathway are managed by the endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation (ERAD) pathway.

Differently from the UPS and the ERAD pathways, autophagy, a self-digestive process triggered by nutrient deprivation, aging, and other stressful conditions including energy shortage, heath shock, and oxidative stress, is important for long-lived proteins and organelles clearance. It requires the participation of a number of proteins encoded by autophagy-related genes (Atg) that are necessary to the formation of autophagosomes, double membrane vesicles, where the cargo material is engulfed and their subsequent delivery to lysosomes for degradation [172]. In addition to the proteostasis network, the cells can also alleviate intracellular accumulation of misfolded proteins through a selective secretion of damaged proteins and RNAs into vesicles of endosomal origin, called exosomes. Several evidences have stressed a crosstalk between the autophagic pathway and the exososomes [173].

The proteostasis network can decline permanently or transiently following development, aging, and exposure to environmental stress, and this decline may contribute to adult-onset proteotoxic disorders and their progression. In particular, a continuous reduction of the efficiency of the proteostasis network may induce pathological aging with accumulation of abnormal proteins, a common feature of many oncological, neurodegenerative, metabolic, and cardiovascular disorders. Proteostasis deregulation at the level of the ER is one of the major contributors to aging and cancer as well [174]. Indeed, harmful stimuli, such as oxidative stress and disruptions of the secretory process may contribute to deposition of unfolded or misfolded proteins at the ER lumen, thus upregolating the endoplasmic reticuluym (ER) stress response [175]. Finally, cancer cells accumulate genetic changes resulting in the presence of mutated proteins; accordingly, most cancer cells are closely dependent on the proteostasis network for survival.

Scientific evidence shows that natural molecules, such as polyphenols, exhibit healthy and protective effects as consequence of their ability not only to maintain the proper oxidant/antioxidant balance in cells, but also for their anti-inflammatory power together with their ability to control the activity of signaling pathways responsible with cell survival, proliferation, and migration. Moreover, the pleiotropic anti-amyloid properties of the polyphenols indicate that these molecules may be useful for treatment of several amyloidosis, notably T2DM and several neurodegenerative diseases. Indeed, many plant polyphenols can reduce the aggregation of some proteins/peptides involved in metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases and can directly or indirectly enhance the clearance of misfolded proteins by modulating the activity of the proteostasis network. However, recent data indicate that increased efficiency of proteostasis and stress resistance may also favor cancer progression. The stresses accomplished by cancer cells require active chaperone platforms to limit protein misfolding and aggregation; the latter, in these cells, may result from high levels of protein synthesis and metabolic requests, oxidative stress, growth under hypoxic and acidic conditions, and protein expression in altered stoichiometries resulting from aneuploidy [176]. The modulation of the proteostasis network by small regulatory molecules can provide a previously unexploited and potentially powerful approach to improve proteome balance.

Resveratrol, one of the most investigated plant polyphenols, displays eclectic biochemical behavior; in fact, it acts upstream of several signaling cascades, likely upon binding to membrane receptor(s); actually, potential binding sites were detected in the plasma membrane of neuronal cells and, to a lesser extent, in nuclear and cellular fractions of rat brain homogenates [177]. In addition, resveratrol mimics some aspects of the CR by inhibiting cAMP phosphodiesterase with activation of AMPK, with reduced fat accumulation, increased glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, mitochondrial biogenesis, and physical endurance. Besides its antioxidant activity [178], resveratrol reduces both intracellular and secreted Aβ in cell culture by activating chaperones such as Hsp70 and by inducing proteasome-dependent Aβ degradation [179]. In addition, resveratrol activates SIRT-1, increases AMPK activity, thus reducing Aβ-induced death signals, such as NF-κB signaling and p53 activity [179] and triggering the degradation of Aβ aggregates by autophagy [178]. The anti-cancer property of resveratrol occurs by inducing caspase 8- and caspase 3-dependent apoptosis via ROS-induced autophagy in human colon cancer cells [180]. In androgen-independent prostate cancer cells, resveratrol induces autophagy-mediated cell death through regulation of store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) mechanisms, and down-regulation of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) expression. In addition, resveratrol triggers ER stress by depleting the pool of ER calcium [181]. Resveratrol has also been shown to decrease the proliferation of breast cancer stem-like cells by inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [182]. Finally, resveratrol has been shown to act as an inhibitor of global protein synthesis in the H4-II-E rat hepatoma cell line. This effect was reached through modulation of mTOR self-phosphorylation and hence of mTOR-dependent and mTOR-independent signaling by reduced formation of the eIF4F translation initiation complex and increased phosphorylation of eIF2α with inhibition of translation [183]. Other findings in renal tissues of rats fed with resveratrol after unilateral uretral obstruction point to the reduced expression of eIF2α and the ensuing reduced levels of ATF4 [184].

Other plant polyphenols have been investigated for their ability to control the proteostasis system at several levels. Curcumin displays several beneficial effects in different in vivo models of aging, ischemia, trauma, and neurodegeneration. In in vivo models of proteinopathies, curcumin reduces plaque burden and improves cognitive function [185]. In addition, curcumin has been shown to induce the expression of Hsp genes and the nuclear translocation of Hsf1, a master regulator of Hsp expression [186]. Green tea catechins show conformational similarities to chaperones and a chaperone-like activity [187]. Phenolic and flavonoid components present in bee pollen activate the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome in HFL-1 human embryonic fibroblasts [188]. OLE displays neuroprotection by increasing proteasome activity, and extending the life span of human IMR90 and WI-38 embryonic fibroblasts [189]. The administration of OLE to the C. elegans C2006 strain expressing Aβ42 in muscle cells induced a significant reduction of amyloid plaque and toxic oligomer formation, with reduction of the extent of paralysis and increased lifespan [69]. The dietary administration of OLE also improved the cognitive performance of the TgCRND8 mouse model of Aβ deposition resulting from reduced plaque deposits, increased microglia migration to the plaques for phagocytosis, and an intense autophagic reaction followed by modulation of the mTOR/AMPK pathways [10][39]. Recent data with cardiomyocytes indicate that OLE counteracts MAO-A cytotoxicity and that this effect results from restoration of restoration of the defective autophagic flux, as indicated by the increase of autolysosomes, indicative of autophagosome–lysosome fusion. Interestingly, autophagy induction involved nuclear translocation and activation of the master gene for lysosomal biogenesis TFEB, suggesting a role of OLE as a TFEB activator [190].

Quercetin has been shown to have neuroprotective effect in various in vitro and in vivo systems. In malignant mesothelioma, quercetin inhibits cell growth and increases the levels of Nrf2, with the transcriptional activation of genes involved in the control of the cellular redox status [191]. In addition, quercetin may induce the expression of chaperones and of proteasome subunits through the Nrf2 pathway [192]. In primary effusion B cell lymphoma, quercetin induces apoptosis and autophagy by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and STAT3 signaling pathways, with the ensuing down-regulation of the expression of pro-survival cellular proteins such as c-FLIP, cyclin D1, and cMyc [193].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms21041250

References

- Stefani, M.; Rigacci, S. Beneficial properties of natural phenols: Highlight on protection against pathological conditions associated with amyloid aggregation. BioFactors 2014, 40, 482–493.

- Bravo, L. Polyphenols: Chemistry, dietary sources, metabolism and nutritional significance. Nutr. Rev. 1998, 56, 313–333.

- Dinda, B.; Debnath, S.; Banik, R. Naturally Occurring Iridoids and Secoiridoids. An Updated Review, Part 4. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 2011, 59, 803–833.

- Dinda, B.; Dubnath, S.; Harigaya, Y. Naturally Occurring Iridoids. A Review, Part 1. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 2007, 55, 159–222.

- Ranalli, A.; Marchegiani, D.; Contento, S.; Girardi, F.; Nicolosi, M.P.; Brullo, M.D. Variations of the iridoid oleuropein in Italian olive varieties during growth and maturation. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2009, 111, 678–687.

- Servili, M.; Montedoro, G.F. Contribution of phenolic compounds in virgin olive oil quality. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2002, 104, 602–613.

- Fujiwara, Y.; Tsukahara, C.; Ikeda, N.; Sone, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Ichi, I.; Koike, T.; Aoki, Y. Oleuropein improves insulin resistance in skeletal muscle by promoting the translocation of GLUT4. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2017, 61, 196–202.

- Wu, L.; Velander, P.; Liu, D.; Xu, B. Olive Component Oleuropein Promotes β-Cell Insulin Secretion and Protects β-Cells from Amylin Amyloid-Induced Cytotoxicity. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 5035–5039.

- Abuznait, A.H.; Qosa, H.; Busnena, B.A.; El Sayed, K.A.; Kaddoumi, A. Olive-oil-derived oleocanthal enhances β-amyloid clearance as a potential neuroprotective mechanism against Alzheimer’s disease: In vitro and in vivo studies. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013, 4, 973–982.

- Grossi, C.; Rigacci, S.; Ambrosini, S.; Ed Dami, T.; Luccarini, I.; Traini, C.; Failli, P.; Berti, A.; Casamenti, F.; Stefani, M. The polyphenol oleuropein aglycone protects TgCRNDmice against Aβ plaque pathology. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71762.

- Monti, M.C.; Margarucci, L.; Riccio, R.; Casapullo, A. Modulation of tau protein fibrillization by oleocanthal. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 1584–1588.

- Rigacci, S.; Guidotti, V.; Bucciantini, M.; Parri, M.; Nediani, C.; Cerbai, E.; Stefani, M.; Berti, A. Oleuropein aglycon prevents cytotoxic amyloid aggregation of human amylin. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2010, 8, 726–735.

- Daccache, A.; Lion, C.; Sibille, N.; Gerard, M.; Slomianny, C.; Lippens, G.; Cotelle, P. Oleuropein and derivatives from olives as Tau aggregation inhibitors. Neurochem. Int. 2011, 58, 700–707.

- Qosa, H.; Mohamed, L.A.; Batarseh, Y.S.; Alqahtani, S.; Ibrahim, B.; LeVine, H., III; Keller, J.N.; Kaddoumi, A. Extra-virgin olive oil attenuates amyloid-β and tau pathologies in the brains of TgSwDI mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 1479–1490.

- Leri, M.; Natalello, A.; Bruzzone, E.; Stefani, M.; Bucciantini, M. Oleuriopein aglycone and hydroxytyrosol interfere differently with toxic Aβ1-aggregation. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 129, 1–12.

- Yu, G.; Deng, A.; Tang, W.; Ma, J.; Yuan, C.; Ma, J. Hydroxytyrosol induces phase II detoxifying enzyme expression and effectively protects dopaminergic cells against dopamine- and 6-hydroxydopamine induced cytotoxicity. Neurochem. Int. 2016, 96, 113–120.

- Nardiello, P.; Pantano, D.; Lapucci, A.; Stefani, M.; Casamenti, F. Diet supplementation with hydroxytyrosol ameliorates brain pathology and restores cognitive functions in a mouse model of amyloid-β deposition. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 63, 1161–1172.

- Biessels, G.J.; Reagan, L.P. Hippocampal insulin resistance and cognitive dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 16, 660–671.

- Bedse, G.; Di Domenico, F.; Serviddio, G.; Cassano, T. Aberrant insulin signaling in Alzheimer’s disease: Current knowledge. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 204.

- Bach-Faig, A.; Berry, E.M.; Lairon, D.; Reguant, J.; Trichopoulou, A.; Dernini, S.; Medina, F.X.; Battino, M.; Belahsen, R.; Miranda, G.; et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Mediterranean Diet Foundation Expert Group. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2274–2284.

- Williams, R.J.; Spencer, J.P.; Rice-Evans, C. Flavonoids: Antioxidants or signalling molecules? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 36, 838–849.

- Halliwell, B. Role of free radicals in the neurodegenerative diseases: Therapeutic implications for antioxidant treatment. Drugs Aging 2001, 18, 685–716.

- Ayissi, V.B.O.; Ebrahimi, A.; Schluesenner, H. Epigenetic effects of natural polyphenols: A focus on SIRT1-mediated mechanisms. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 22–32.

- Bartolini, G.; Petruccelli, R. Classifications, Origins, Diffusion and History of the Olive; Rome Food and Agricolture Organisation in the United Nations: Roma, Italy, 2002.

- Flemmig, J.; Rusch, D.; Czerwinska, M.E.; Ruwald, H.W.; Arnhold, J. Components of a standardized olive leaf dry extract (Ph. Eur.) promote hypothiocyanate production by lactoperoxidase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 549, 17–25.

- Flemming, J.; Kuchta, K.; Arnhold, J.; Rauwald, H.W. Olea europaea leaf (Ph. Eur.) extract as well as several of its isolated phenolics inhibit the gout-related enzyme xanthine oxidase. Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 561–566.

- Calixto, J.B.; Campos, M.M.; Otuki, M.F.; Santos, A.R. Anti-inflammatory compounds of plant origin. Part II. Modulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules. Planta Med. 2004, 70, 93–103.

- Colomer, R.; Sarrats, A.; Lupu, R.; Puig, T. Natural Polyphenols and their Synthetic Analogs as Emerging Anticancer Agents. Curr. Drug Targets 2017, 18, 147–159.

- Toric, J.; Markovic, A.K.; Brala, C.J.; Barbaric, M. Anticancer effects of olive oil polyphenols and their combinations with anticancer drugs. Acta Pharm. 2019, 69, 461–482.

- Rigacci, S.; Stefani, M. Nutraceuticals and amyloid neurodegenerative diseases: A focus on natural polyphenols. Exp. Rev. Neurother. 2014, 15, 41–52.

- Tomaselli, S.; La Vitola, P.; Pagano, K.; Brandi, E.; Santamaria, G.; Galante, D.; D’Arrigo, C.; Moni, L.; Lambruschini, C.; Banfi, L.; et al. Biophysical and in vivo studies identify a new natural-based polyphenol, counteracting Aβ oligomerization in vitro and Aβ oligomer-mediated memory impairment and neuroinflammation in an acute mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 4452–4465.

- Curti, V.; Zaccaria, V.; Tsetegho Sokeng, A.J.; Dacrema, M.; Masiello, I.; Mascaro, A.; D’Antona, G.; Daglia, M. Bioavailability and In Vivo Antioxidant Activity of a Standardized Polyphenol Mixture Extracted from Brown Propolis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1250.

- Gumireddy, A.; Christman, R.; Kumari, D.; Tiwari, A.; North, E.J.; Chauhan, H. Preparation, Characterization, and In vitro Evaluation of Curcumin- and Resveratrol-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles. AAPS Pharm. Sci. Tech. 2019, 20, 145.

- Jaisamut, P.; Wiwattanawongsa, K.; Wiwattanapatapee, R. A Novel Self-Microemulsifying System for the Simultaneous Delivery and Enhanced Oral Absorption of Curcumin and Resveratrol. Planta Med. 2017, 83, 461–467.

- Chimento, A.; De Amicis, F.; Sirianni, R.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Puoci, F.; Casaburi, I.; Saturnino, C.; Pezzi, V. Progress to Improve Oral Bioavailability and Beneficial Effects of Resveratrol. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1381.

- Vissers, M.N.; Zock, P.L.; Roodenburg, A.J.C.; Leenen, R.; Katan, M.B. Olive oil phenols are absorbed in humans. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 409–417.

- De Bock, M.; Thorstensen, E.B.; Derraik, J.G.B.; Henderson, H.V.; Hofman, P.L.; Cutfield, W.S. Human absorption and metabolism of oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol ingested as olive (Olea europaea L.) leaf extract. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 2079–2085.

- Garcia-Villalba, R.; Larrosa, M.; Possemiers, S.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Espín, J.C. Bioavailability of phenolics from an oleuropein-rich olive (Olea europaea) leaf extract and its acute effect on plasma antioxidant status: Comparison between pre- and postmenopausal women. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 1015–1027.

- Luccarini, I.; Grossi, C.; Rigacci, S.; Coppi, E.; Pugliese, A.M.; Pantano, D.; la Marca, G.; ed Dami, T.; Berti, A.; Stefani, M.; et al. Oleuropein aglycone protects against pyroglutamylated-amyloid-β toxicity: Biochemical, epigenetic and functional correlates. Neurobiol. Aging 2015, 36, 648–663.

- Lòpez de las Hazas, M.-C.; Godinho-Pereira, J.; Macià, A.; Filipa Almeida, A.; Ventura, M.R.; Motilva, M.-J.; Santos, C.N. Brain uptake of hydroxytyrosol and its main circulating metabolites: Protective potential in neuronal cells. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 46, 110–117.

- De Pablos, R.M.; Espinosa-Oliva, A.M.; Hornado-Ortega, R.; Cano, M.; Arguelles, S. Hydroxytyrosol protects from aging process via AMPK and autophagy; a review of ots effects on cancer, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, immune-mediated and neurodegenerative diseases. Pharm. Res. 2019, 143, 58–72.

- Casamenti, F.; Stefani, M. Olive polyphenols: New promising agents to combat aging-associated neurodegeneration. Exp. Rev. Neurother. 2017, 17, 345–358.

- Trovato Salinaro, A.; Cornelius, C.; Koverech, G.; Koverech, A.; Scuto, M.; Lodato, F.; Fronte, V.; Muccilli, V.; Reibaldi, M.; Longo, A.; et al. Cellular stress response, redox status, and vitagenes in glaucoma: A systemic oxidant disorderlinked to Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 129.

- Wakabayashi, N.; Itoh, K.; Wakabayashi, J.; Motohashi, H.; Noda, S.; Takahashi, S.; Imakado, S.; Kotsuji, T.; Otsuka, F.; Roop, D.R.; et al. Keap1-null mutation leads to post-natal lethality due to constitutive Nrfactivation. Nat. Genet. 2003, 35, 238–245.

- Calabrese, V.; Cornelius, C.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Calabrese, E.J.; Mattson, M.P. Cellular stress responses, the hormesis paradigm, and vitagenes: Novel targets for therapeutic intervention in neurodegenerative disorders. Antioxid. RedoxSignal. 2010, 13, 1763–1811.

- Trovato Salinaro, A.; Pennisi, M.; Di Paola, R.; Scuto, M.; Crupi, R.; Cambria, M.T.; Ontario, M.L.; Tomasello, M.; Uva, M.; Maiolino, L.; et al. Neuroinflammation and neurohormesis in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer-linked pathologies: Modulation by nutritional mushrooms. Immun. Ageing 2018, 15, 8.

- Scuto, M.; Di Mauro, P.; Ontario, M.L.; Amato, C.; Modafferi, S.; Ciavardelli, D.; Trovato Salinaro, A.; Maiolino, L.; Calabrese, V. Nutritional Mushroom Treatment in Meniere’s Disease with Coriolus versicolor: A Rationale for Therapeutic Intervention inNeuroinflammation and Antineurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 21, E284.

- Mattson, M.P. Hormesis and disease resistance: Activation of cellular stressresponse pathways. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2008, 27, 155–162.

- Cornelius, C.; Trovato Salinaro, A.; Scuto, M.; Fronte, V.; Cambria, M.T.; Pennisi, M.; Bella, R.; Milone, P.; Graziano, A.; Crupi, R.; et al. Cellular stress response, sirtuins and UCP proteins in Alzheimer disease: Role of vitagenes. Immun. Ageing 2013, 10, 41.

- Mancuso, C.; Santangelo, R.; Calabrese, V. The hemeoxygenase/biliverdin reductase system: A potential drug target in Alzheimers disease. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2013, 27 (Suppl. 2), 75–87.

- Naviaux, R.K. Metabolic features and regulation of the healing cycle-A new modelfor chronic disease pathogenesis and treatment. Mitochondrion 2019, 46, 278–297.

- Scuto, M.C.; Mancuso, C.; Tomasello, B.; Laura Ontario, M.; Cavallaro, A.; Frasca, F.; Maiolino, L.; Trovato Salinaro, A.; Calabrese, E.J.; Calabrese, V. Curcumin, Hormesis and the Nervous System. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2417.

- Frey, B.; Hehlgans, S.; Rodel, F.; Gaipl, U.S. Modulation of inflamma- tion by low and high doses of ionizing radiation: Implications for benign and malign diseases. Cancer Lett. 2015, 368, 230–237.

- Large, M.; Hehlgans, S.; Reichert, S.; Gaipl, U.S.; Fournier, C.; Rodel, C.; Weiss, C.; Rodel, F. Study of the anti- inflammatory effect of low-dose radiation. The contribution of biphasic regulation of the antioxidative system in endothelial cells. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2015, 191, 742–749.

- Wunderlich, R.; Ernst, A.; Roedel, F.; Fietkau, R.; Ott, O.; Lauber, K.; Frey, B.; Gaipl, U.S. Low and moderate doses of ionizing radiation up to Gy modulate transmigration and chemotaxis of activated macrophages, provoke an anti-inflammatory cytokine milieu, but do not impact upon viability and phagocytic function. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2015, 179, 50–61.

- Trovato, A.; Siracusa, R.; Di Paola, R.; Scuto, M.; Ontario, M.L.; Bua, O.; Di Mauro, P.; Toscano, M.A.; Petralia, C.C.T.; Maiolino, L.; et al. Redox modulation of cellular stress response and lipoxin Aexpression by Hericium Erinaceus in rat brain: Relevance to Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Immun. Ageing 2016, 13, 23.

- Trovato, A.; Siracusa, R.; Di Paola, R.; Scuto, M.; Fronte, V.; Koverech, G.; Luca, M.; Serra, A.; Toscano, M.A.; Petralia, A.; et al. Redox modulation of cellular stress response and lipoxin Aexpression by Coriolus versicolor in rat brain: Relevance to Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Neurotoxicology 2016, 53, 350–358.

- Calabrese, V.; Santoro, A.; Monti, D.; Crupi, R.; Di Paola, R.; Latteri, S.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Zappia, M.; Giordano, J.; Calabrese, E.J.; et al. Aging and Parkinson’s Disease: Inflammaging, neuroinflammation and biological remodeling as key factors in pathogenesis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 115, 80–91.

- Liu, B.; Hong, J.S. Role of microglia in inflammation-mediated neurodegenerative diseases: Mechanisms and strategies for therapeutic intervention. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 304, 1–7.

- Tan, M.S.; Yu, J.T.; Jiang, T.; Zhu, X.C.; Tan, L. The NLRPinflammasome in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2013, 48, 875–882.

- Freeman, D.; Cedillos, R.; Choyke, S.; Lukic, Z.; McGuire, K.; Marvin, S.; Burrage, A.M.; Sudholt, S.; Rana, A.; O’Connor, C.; et al. Alpha-synuclein induces lysosomal rupture and cathepsin dependent reactive oxy-gen species following endocytosis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62143.

- Heneka, M.T.; Kummer, M.P.; Stutz, A.; Delekate, A.; Schwartz, S.; Vieira-Saecker, A.; Griep, A.; Axt, D.; Remus, A.; Tzeng, T.C.; et al. NLRPis activated in Alzheimer’s disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PSmice. Nature 2013, 493, 674–678.

- Codolo, G.; Plotegher, N.; Pozzobon, T.; Brucale, M.; Tessari, I.; Bubacco, L.; de Bernard, M. Triggering of inflammasome by aggregated alpha-synuclein, an inflammatory response in synucleinopathies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55375.

- Berr, C.; Portet, F.; Carriere, I.; Akbaraly, T.N.; Feart, C.; Gourlet, V.; Combe, N.; Barberger-Gateau, P.; Ritchie, K. Olive oil and cognition: Results from the three-city study. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2009, 28, 357–364.

- Féart, C.; Samieri, C.; Allès, B.; Barberger-Gateau, P. Potential benefits of adherence to the Mediterranean diet on cognitive health. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013, 72, 140–152.

- Kostomoiri, M.; Fragkouli, A.; Sagnou, M.; Skaltsounis, L.A.; Pelecanou, M.; Tsilibary, E.C.; Tzinia, A.K. Oleuropein, an anti-oxidant polyphenol constituent of olivepromotes α-secretase cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (AβPP). Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2013, 33, 147–154.

- Ladiwala, A.R.; Mora-Pale, M.; Lin, J.C.; Bale, S.S.; Fishman, Z.S.; Dordick, J.S.; Tessier, P.M. Polyphenolic glycosides and aglycones utilize opposing pathways to selectively remodel and inactivate toxic oligomers of amyloid β. Chembiochem 2011, 12, 1749–1758.

- Kim, M.H.; Min, J.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Chae, U.; Yang, E.J.; Song, K.S.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, S.R.; Lee, D.S. Oleuropein isolated from Fraxinus rhynchophylla inhibits glutamate-induced neuronal cell death by attenuating mitochondrial dysfunction. Nutr. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 520–528.

- Diomede, L.; Rigacci, S.; Romeo, M.; Stefani, M.; Salmona, M. Oleuropein Aglycone Protects Transgenic, C. elegans Strains Expressing Aβby Reducing Plaque Load and Motor Deficit. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58893.

- Shibani, F.; Sahamsizadeh, A.; Fatemi, I.; Allahtavakoli, M.; Hasanshahi, J.; Rahmani, M.; Azin, M.; Hassanipour, M.; Mozafari, N.; Kaeidi, A. Effect of oleuropein on morphine-induced hippocampus neurotoxicity and memory impairments in rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2019, 392, 1383–1391.

- De la Torre, R.; Covas, M.I.; Pujadas, M.A.; Fito, M.; Farre, M. Is dopamine behind the health benefits of red wine? Eur. J. Nutr. 2006, 45, 307–310.

- Xu, C.L.; Sim, M.K. Reduction of dihydroxyphenylacetic acid by a novel enzyme in the rat brain. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995, 50, 1333–1337.

- Goldstein, D.S.; Jinsmaa, Y.; Sullivan, P.; Holmes, C.; Kopin, I.J.; Sharabi, Y. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylethanol (Hydroxytyrosol) Mitigates the Increase in Spontaneous Oxidation of Dopamine During Monoamine Oxidase Inhibition in PCCells. Neurochem. Res. 2016, 41, 2173–2178.

- Jinsmaa, Y.; Isonaka, R.; Sharabi, Y.; Goldstein, D. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde is more efficient than dopamine in oligomerizing and quinonizing alpha-synuclein. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2019.

- Safouris, A.; Tsivgoulis, G.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Psaltopoulou, T. Mediterranean Diet and Risk of Dementia. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2015, 12, 736–744.

- Psaltopoulou, T.; Sergentanis, T.N. Mediterranean diet may reduce Alzheimer’s risk. Evid. Based. Med. 2015, 20, 202.

- Peng, Y.; Hou, C.; Yang, Z.; Li, C.; Jia, L.; Liu, J.; Tang, Y.; Shi, L.; Li, Y.; Long, J.; et al. Hydroxytyrosol mildly improve cognitive function independent of APP processing inAPP/PSmice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 2331–2342.

- Palazzi, L.; Leri, M.; Cesaro, S.; Stefani, M.; Bucciantini, M.; Polverino de Laureto, P. Insight into the molecular mechanism underlying the inhibition of α-synuclein aggregation by hydroxytyrosol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, in press.

- Reutzel, M.; Grewal, R.; Silaidos, C.; Zotzel, J.; Marx, S.; Tretzel, J.; Eckert, G.P. Effects of Long-Term Treatment with a Blend of Highly Purified Olive Secoiridoids on Cognition and Brain ATP Levels in Aged NMRI Mice. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 4070935.

- Funakohi-Tago, M.; Sakata, T.; Fujiwara, S.; Sakakura, A.; Sugai, T.; Tago, K.; Tamura, H. Hydroxytyrosol butyrate inhibits 6-OHDA-induced apoptosis through activation of the Nrf2/HO-axis in SH-SY5Y cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 834, 246–256.

- Zheng, A.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Cao, K.; Li, H.; Pu, W.; Yang, Z.; Peng, Y.; Long, J.; Liu, J.; et al. Hydroxytyrosol improves mitochondrial function and reduces oxidative stress in the brain of db/db mice: Role of AMP-activated protein kinase activation. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1667–1676.

- Sun, W.; Wang, X.; Hou, C.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Guo, J.; Huo, C.; Wang, M.; Miao, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Oleuropein improves mitochondrial function to attenuate oxidative stress by activating the Nrfpathway in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Neuropharmacology 2017, 113, 556–566.

- Zrelli, H.; Kusunoki, M.; Miyazaki, H. Role of Hydroxytyrosol-dependent Regulation of HO-Expression in Promoting Wound Healing of Vascular Endothelial Cells via NrfDe Novo Synthesis and Stabilization. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 1011–1018.

- Wei, Y.; Jia, J.; Jin, X.; Tong, W.; Tian, H. Resveratrol ameliorates inflammatory damage and protects against osteoarthritis in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 1493–1498.

- Montoya, T.; Aparicio-Soto, M.; Castejón, M.L.; Rosillo, M.Á.; Sánchez-Hidalgo, M.; Begines, P.; Fernández-Bolaños, J.G.; Alarcón-de-la-Lastra, C. Peracetylated hydroxytyrosol, a new hydroxytyrosol derivate, attenuates LPS-induced inflammatory response in murine peritoneal macrophages via regulation of non-canonical inflammasome, Nrf2/HOand JAK/STAT signaling pathways. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 57, 110–120.

- Kumar, R.; Nigam, L.; Singh, A.P.; Singh, K.; Subbarao, N.; Dey, S. Design, synthesis of allosteric peptide activator for human SIRTand its biological evaluation in cellular model of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 127, 909–916.

- Herskovits, A.Z.; Guarente, L. SIRTin neurodevelopment and brain senescence. Neuron 2014, 81, 471–483.

- Gao, J.; Wang, W.Y.; Mao, Y.W.; Gräff, J.; Guan, J.S.; Pan, L.; Mak, G.; Kim, D.; Su, S.C.; Tsai, L.H. A novel pathway regulates memory and plasticity via SIRTand miR-134. Nature 2010, 466, 1105–1109.

- Zhi, L.Q.; Yao, S.X.; Liu, H.L.; Li, M.; Duan, N.; Ma, J.B. Hydroxytyrosol inhibits the inflammatory response of osteoarthritis chondrocytes via SIRT6-mediated autophagy. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 4035–4042.

- Sun, T.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, S.Y.; Wu, Q.; Liao, C.R.; Wang, Z.; Wu, X.H.; Wu, H.T.; Chen, J.T. Hydroxytyrosol promotes autophagy by regulating SIRTagainst advanced oxidation protein product-induced NADPH oxidase and inflammatory response. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 1531–1540.

- Gallardo-Fernández, M.; Hornedo-Ortega, R.; Cerezo, A.B.; Troncoso, A.M.; García-Parrilla, M.C. Melatonin, protocatechuic acid and hydroxytyrosol effects on vitagenes system against alpha-synuclein toxicity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 134, 110817.

- Wang, W.; Jing, T.; Yang, X.; He, Y.; Wang, B.; Xiao, Y.; Shang, C.; Zhang, J.; Lin, R. Hydroxytyrosol regulates the autophagy of vascular adventitial fibroblasts through the SIRT1-mediated signaling pathway. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 96, 88–96.

- Yang, X.; Jing, T.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, B.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Wei, J.; et al. Hydroxytyrosol Attenuates LPS-Induced Acute Lung Injury in Mice by Regulating Autophagy and Sirtuin Expression. Curr. Mol. Med. 2017, 17, 149–159.

- Calabrese, V.; Scapagnini, G.; Davinelli, S.; Koverech, G.; Koverech, A.; De Pasquale, C.; Salinaro, A.T.; Scuto, M.; Calabrese, E.J.; Genazzani, A.R. Sex hormonal regulation and hormesis in aging and longevity: Role of vitagenes. J. Cell. Commun. Signal. 2014, 8, 369–384.

- Amara, I.; Timoumi, R.; Annabi, E.; Di Rosa, G.; Scuto, M.; Najjar, M.F.; Calabrese, V.; Abid-Essefi, S. Di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate targets the thioredoxin system and the oxidative branch of the pentose phosphate pathway in liver of Balb/c mice. Environ Toxicol. 2020, 35, 78–86.

- Peng, S.; Zhang, B.; Yao, J.; Duan, D.; Fang, J. Dual protection of hydroxytyrosol, an olive oil polyphenol, against oxidative damage in PCcells. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 2091–2100.

- Zhang, Y.; Ahn, Y.H.; Benjamin, I.J.; Honda, T.; Hicks, R.J.; Calabrese, V.; Cole, P.A.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. HSF1-dependent upregulation of Hspby sulfhydryl-reactive inducers of the KEAP1/NRF2/ARE pathway. Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 1355–1361.

- An, Y.W.; Jhang, K.A.; Woo, S.Y.; Kang, J.L.; Chong, Y.H. Sulforaphane exerts its anti-inflammatory effect against amyloid-β peptide via STAT-dephosphorylation and activation of Nrf2/HO-cascade in human THP-macrophages. Neurobiol. Aging 2016, 38, 1–10.

- Lee, S.; Choi, B.R.; Kim, J.; La Ferla, F.M.; Park, J.H.Y.; Han, J.S.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, J. Sulforaphane Upregulates the Heat Shock Protein Co-Chaperone CHIP and Clears Amyloid-β and Tau in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, e1800240.

- Moussa, C.; Hebron, M.; Huang, X.; Ahn, J.; Rissman, R.A.; Aisen, P.S.; Turner, R.S. Resveratrol regulates neuro-inflammation and induces adaptive immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2017, 14, 1.

- Zhao, Y.N.; Li, W.F.; Li, F.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, Y.D.; Xu, A.L.; Qi, C.; Gao, J.M.; Gao, J. Resveratrol improves learning and memory in normally aged mice through microRNA-CREB pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 435, 597–602.

- Laudati, G.; Mascolo, L.; Guida, N.; Sirabella, R.; Pizzorusso, V.; Bruzzaniti, S.; Serani, A.; Di Renzo, G.; Canzoniero, L.M.T.; Formisano, L. Resveratrol treatment reduces the vulnerability of SH-SY5Y cells and cortical neurons overexpressing SOD1-G93A to Thimerosal toxicity through SIRT1/DREAM/PDYN pathway. Neurotoxicology 2019, 71, 6–15.

- Zhang, S.; Gao, L.; Liu, X.; Lu, T.; Xie, C.; Jia, J. Resveratrol Attenuates Microglial Activation via SIRT1-SOCSPathway. Evid. Based. Complement Alternat. Med. 2017, 2017, 8791832.

- Ma, S.; Feng, J.; Zhang, R.; Chen, J.; Han, D.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Li, X.; Fan, M.; Li, C.; et al. SIRTActivation by Resveratrol Alleviates Cardiac Dysfunction via Mitochondrial Regulation in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy Mice. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 4602715.

- Hui, Y.; Chengyong, T.; Cheng, L.; Haixia, H.; Yuanda, Z.; Weihua, Y. Resveratrol attenuates the cytotoxicity induced by amyloid-β 1–in PCcells by upregulating heme oxygenase-via the PI3K/Akt/Nrfpathway. Neurochem. Res. 2018, 43, 297–305.

- Zhou, Y.; Jin, Y.; Yu, H.; Shan, A.; Shen, J.; Zhou, C.; Zhao, Y.; Fang, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Resveratrol inhibits aflatoxin B1-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in bovine mammary epithelial cells and is involved the Nrfsignaling pathway. Toxicon 2019, 164, 10–15.

- Feng, L.; Zhang, L. Resveratrol Suppresses Aβ-Induced Microglial Activation Through the TXNIP/TRX/NLRPSignaling Pathway. DNA Cell Biol. 2019, 38, 874–879.

- Mhillaj, E.; Cuomo, V.; Trabace, L.; Mancuso, C. The HemeOxygenase/Biliverdin Reductase System as Effector of the Neuroprotective Outcomes of Herb-BasedNutritionalSupplements. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1298.

- Xu, J.; Zhou, L.; Weng, Q.; Xiao, L.; Li, Q. Curcumin analogues attenuate Aβ 25—Induced oxidative stress in PCcells via Keap1/Nrf2/HO-signaling pathways. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2019, 305, 171–179.

- Yin, H.; Guo, Q.; Li, X.; Tang, T.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y.; Feng, Q.; Ma, C.; Gao, C.; et al. Curcumin Suppresses IL-1β Secretion and Prevents Inflammation through Inhibition of the NLRPInflammasome. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 2835–2846.

- Ma, Q.L.; Zuo, X.; Yang, F.; Ubeda, O.J.; Gant, D.J.; Alaverdyan, M.; Teng, E.; Hu, S.; Chen, P.P.; Maiti, P.; et al. Curcumin suppresses soluble tau dimers and corrects molecular chaperone, synaptic, and behavioral deficits in aged human tau transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 4056–4065.

- Maggi, S.; Noale, M.; Gallina, P.; Bianchi, D.; Marzari, C.; Limongi, F.; Crepaldi, G. ILSA Working Group. Metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in an elderly Caucasian cohort: The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006, 61, 505–510.

- Schnack, L.L.; Romani, A.M.P. The Metabolic Syndrome and the Relevance of Nutrients for its Onset. Recent Pat. Biotechnol. 2017, 11, 101–119.

- Trichopoulou, A.; Naska, A.; DAFNE III Group. European food availability databank based on household budget surveys: The Data Food Networking initiative. Eur. J. Public Health 2003, 13 (Suppl. 3), 24–28.

- Soriguer, F.; Rojo-Martinez, G.; Goday, A.; Bosch-Comas, A.; Bordiu, E.; Caballero-Diaz, F.; Calle-Pascual, A.; Carmena, R.; Casamitjana, R.; Castaño, L.; et al. Olive oil has a beneficial effect on impaired glucose regulation and other cardiometabolic risk factors. study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 911–916.

- Tuomilehto, J.; Lindström, J.; Eriksson, J.G.; Valle, T.T.; Hämäläinen, H.; Ilanne-Parikka, P.; Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S.; Laakso, M.; Louheranta, A.; Rastas, M.; et al. Prevention of type diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 1343–1350.

- Lindström, J.; Peltonen, M.; Eriksson, J.G.; Louheranta, A.; Fogelholm, M.; Uusitupa, M.; Tuomilehto, J. High-fibre, low-fat diet predicts long-term weight loss and decreased type diabetes risk: The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 912–920.

- Hanhineva, K.; Torronen, R.; Bondia-Pons, I.; Pekkinen, J.; Kolehmainen, M.; Mykkanen, H.; Poutanen, K. Impact of dietary polyphenols on carbohydrate metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 1365–1402.

- Valdivielso, P.; Puerta, S.; Rioja, J.; Alonso, I.; Ariza, M.J.; Sánchez-Chaparro, M.A.; Palacios, R.; González-Santos, P. Postprandial apolipoprotein Bis associated with asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease: A study in patients with type diabetes and controls. Clin. Chim. Acta 2010, 411, 433–437.

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Hruby, A.; Salas-Salvadò, J.; Martinez-Gonzàlez, M.A.; Sun, Q.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Olive oil consumption and risk of type diabetes in US women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 479–486.

- O’Keefe, J.H.; Bell, D.S.H. Postprandial hyperglycemia/hyperlipidemia (postprandial dysmetabolism) is a cardiovascular risk factor. Am. J. Cardiol. 2007, 100, 899–904.

- Meigs, J.B.; Nathan, D.M.; D’Agostino, R.B., Sr.; Wilson, P.W.; Framingham Offspring Study. Fasting and postchallenge glycemia and cardiovascular disease risk: The Framingham offspring study. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 1845–1850.

- Harte, A.L.; Varma, M.C.; Tripathi, G.; McGee, K.C.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Al-Attas, O.S.; Sabico, S.; O’Hare, J.P.; Ceriello, A.; Saravanan, P.; et al. High fat intake leads to acute postprandial exposure to circulating endotoxin in type diabetic subjects. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 375–382.

- Nocella, C.; Carnevale, R.; Bartimoccia, S.; Novo, M.; Cangemi, R.; Pastori, D.; Calvieri, C.; Pignatelli, P.; Violi, F. Lipopolysaccharide as trigger of platelet aggregation via eicosanoid over-production. Thromb. Haemost. 2017, 117, 1558–1570.

- El-Amin, M.; Virk, P.; Elobeid, M.A.; Almarhoon, Z.M.; Hassan, Z.K.; Omer, S.A.; Merghani, N.M.; Daghestani, M.H.; Al-Olayan, E.M. Anti-diabetic effect of Murraya koenigii (L) and Olea europaea (L) leaf extracts on streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 26, 359–365.

- Carnevale, R.; Pignatelli, P.; Nocella, C.; Loffredo, L.; Pastori, D.; Vicario, T.; Petruccioli, A.; Bartimoccia, S.; Violi, F. Extra virgin olive oil blunt postprandial oxidative stress via NOXdown-regulation. Atherosclerosis 2014, 35, 649–658.

- Carnevale, R.; Pastori, D.; Nocella, C.; Cammisotto, V.; Bartimoccia, S.; Novo, M.; Del Ben, M.; Farcomeni, A.; Angelico, F.; Violi, F. Gut-derived lipopolysaccharides increase post-prandial oxidative stress via Noxactivation in patients with impaired fasting glucose tolerance: Effect of extra-virgin olive oil. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 843–851.

- Wilson, T.; Singh, A.P.; Vorsa, N.; Goettl, C.D.; Kittleson, K.M.; Roe, C.M.; Kastello, G.M.; Ragsdale, F.R. Human glycemic response and phenolic content of unsweetened cranberry juice. J. Med. Food 2008, 11, 46–54.

- Calahorra, J.; Shenk, J.; Wielanga, V.H.; Verweij, V.; Geenen, B.; Dederen, P.J.; Peinado, M.A.; Siles, E.; Wiesmann, M.; Kiliaan, A.J. Hydroxytyroaol, the major phenolic compound of olive oil, as as acute therapeutic strategy after ischemic stroke. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2430.

- Thilagam, E.; Parimaladevi, B.; Kumarappan, C.; Mandal, S.C. α-Glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitory activity of Senna surattensis. J. Acupunct. Meridian Stud. 2013, 6, 24–30.

- Hiyoshi, T.; Fujiwara, M.; Yao, Z. Postprandial hyperglycemia and postprandial hypertriglyceridemia in type diabetes. J. Biomed. Res. 2019, 33, 1–16.

- Tadera, K.; Minami, Y.; Takamatsu, K.; Matsuoka, T. Inhibition of alpha-glucosidase and alpha-amylase by flavonoids. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. (Tokyo) 2006, 52, 149–153.

- Matsui, T.; Tanaka, T.; Tamura, S.; Toshima, A.; Tamaya, K.; Miyata, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Matsumoto, K. alpha-Glucosidase inhibitory profile of catechins and theaflavins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 99–105.

- Park, C.E.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, J.H.; Min, B.I.; Bae, H.; Choe, W.; Kim, S.S.; Ha, J. Resveratrol stimulates glucose transport in C2Cmyotubes by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Exp. Mol. Med. 2007, 39, 222–229.

- Song, J.; Kwon, O.; Chen, S.; Daruwala, R.; Eck, P.; Park, J.B.; Levine, M. Flavonoid inhibition of sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter (SVCT1) and glucose transporter isoform (GLUT2), intestinal transporters for vitamin C and Glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 15252–15260.

- Johnston, K.; Sharp, P.; Clifford, M.; Morgan, L. Dietary polyphenols decrease glucose uptake by human intestinal Caco-cells. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579, 1653–1657.

- Calabrese, V.; Santoro, A.; Trovato Salinaro, A.; Modafferi, S.; Scuto, M.; Albouchi, F.; Monti, D.; Giordano, J.; Zappia, M.; Franceschi, C.; et al. Hormetic approaches to the treatment of Parkinson’s disease: Perspectives and possibilities. J. Neurosci. Res. 2018, 96, 1641–1662.

- Montagut, G.; Onnockx, S.; Vaqué, M.; Bladé, C.; Blay, M.; Fernández-Larrea, J.; Pujadas, G.; Salvadó, M.J.; Arola, L.; Pirson, I. Oligomers of grape-seed procyanidin extract activate the insulin receptor and key targets of the insulin signaling pathway differently from insulin. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2010, 21, 476–481.

- Cummings, E.; Hundal, H.S.; Wackerhage, H.; Hope, M.; Belle, M.; Adeghate, E.; Singh, J. Momordica charantia fruit juice stimulates glucose and amino acid uptakes in Lmyotubes. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 261, 99–104.

- Kurimoto, Y.; Shibayama, Y.; Inoue, S.; Soga, M.; Takikawa, M.; Ito, C.; Nanba, F.; Yoshida, T.; Yamashita, Y.; Ashida, H.; et al. Black soybean seed coat extract ameliorates hyperglycemia and insulin sensitivity via the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in diabetic mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 5558–5564.

- Babu, P.V.; Liu, D.; Gilbert, E.R. Recent advances in understanding the anti-diabetic actions of dietary flavonoids. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 1777–1789.