O-GlcNAcylation is a post-translational modification that dynamically modifies serine (Ser) and threonine (Thr) residues of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins through their hydroxyl moieties. O-GlcNAcylation is catalyzed by two key enzymes, namely, O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA), which add/remove UDP-GlcNAc to/from Ser and Thr residues, respectively. O-GlcNAc modification is dependent on the intracellular concentration of UDP-GlcNAc from the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, which integrates carbohydrates, amino acids, fatty acids and nucleic acids metabolism in the process of UPD-GlcNAc synthesis. Protein O-GlcNAcylation is widely recognized as an important cellular nutrient sensor and it may represents a key linkage between nutrient sensing, energy metabolism and signal transduction.

- high-fat diet

- brain insulin resistance

- neurodegeneration

- protein O-GlcNAcylation

- mitochondria

1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome is a series of complex metabolic disorders centering on insulin resistance, obesity, hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, which represents a high-risk factor for a number of pathological conditions including Type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, coronary heart disease, stroke, and cognitive decline [1]. T2DM accounts for 90% of all reported diabetes cases [2,3] and it is attributed to the interaction of multiple genetic and environmental factors. One of the environmental risks is the modern lifestyle with the so-called Western diet, rich in refined carbohydrates, animal fats and edible oils, which leads to nutrient excess and promotes the development of insulin resistance [4]. Systemic and brain insulin resistance, as common features of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and T2DM, play prominent roles in the development of cognitive dysfunction and dementia [5,6,7,8]. Epidemiologic studies indicate that long-term hyperinsulinemia and obesity, caused by dietary fat intake, are risk factors for dementia. Moreover, insulin administered to AD patients, by regulating glucose transport, energy metabolism, neuronal growth, and synaptic plasticity, improves memory formation [9,10,11]. Studies on mice fed with a high-fat diet (HFD), which mimicked a hypercaloric Western-style diet [12], thus leading to obesity and T2DM, demonstrated impaired performance in learning and memory tasks, alterations of synaptic integrity, altered CA1-related long-term depression (LTD) and long-term potentiation (LTP), and the development of AD pathological hallmarks [13,14,15,16]. However, the identification of the exact molecular mechanisms associating perturbations in the peripheral environment with brain function is unclear and effective treatments are lacking. Thus, there is an urgent need to further explore the molecular role of insulin resistance in order to find innovative strategies and key targets for the prevention and treatment of metabolic syndrome. In this scenario, as the nutrient-sensing mechanisms are essential for regulation of metabolism, it might be of great significance to explore the biological mechanisms that link insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and neurodegeneration from the perspective of nutrient recognition and regulation.

In this regard, protein O-GlcNAcylation is widely recognized as an important cellular nutrient sensor and it serves as a key linkage between nutrient sensing, energy metabolism and signal transduction [17]. O-GlcNAcylation is a post-translational modification that dynamically modifies serine (Ser) and threonine (Thr) through their hydroxyl moieties on nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins [18]. O-GlcNAcylation is catalyzed by two key enzymes, namely, O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA), which add/remove UDP-GlcNAc to/from Ser and Thr residues, respectively [19]. O-GlcNAc modification is dependent on the intracellular concentration of UDP-GlcNAc from the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP). The HBP integrates the metabolic information of nutrients, including carbohydrates, amino acids, fatty acids, and nucleic acids, in the process of UPD-GlcNAc synthesis [4]. Further, HBP regulates energy homeostasis by controlling the production of both insulin and leptin, which are hormones playing a critical role in regulating energy metabolism [20]. O-GlcNAcylation is tightly coupled to insulin resistance because hyperglycemia or hyperlipidemia-induced insulin resistance is closely related to altered HBP flux, and in turn, the subsequent aberrant O-GlcNAcylation modifies insulin signaling, glucose uptake, gluconeogenesis, glycogen, and fatty acid synthesis [21]. In this scenario, O-GlcNAcylation represents a key mechanism linking nutrient overload and insulin resistance, and their dysregulation might promote the transition from metabolic defects to chronic diseases such as T2DM and AD [22,23,24,25,26]. Indeed, obesity and peripheral hyperglycemia, by promoting insulin resistance and hypoglycemia at brain level, lead to decreased O-GlcNAcylation of APP and Tau and to increased production of toxic Aβ amyloid and Tau aggregates, which are hallmarks of AD [27,28,29,30,31]. Furthermore, the well-known involvement of O-GlcNAcylation in controlling protein localization, function, and interaction has acquired special interest with regards to APP. Indeed, this posttranslational modification (PTM) has been demonstrated to control APP maturation and trafficking, thus affecting the generation Aβ [32,33,34]. Moreover, mitochondrial dysfunction and the associated oxidative stress have been recognized as important biological mechanisms contributing to insulin resistance and diabetic complications [35,36,37,38]. As well, a number of studies demonstrated that impaired mitochondrial function plays a significant role in neurodegenerative diseases, supporting the notion that AD is primarily a metabolic disorder [14,39,40,41,42,43]. O-GlcNAcylation is known to regulate energy metabolism and the production of metabolic intermediates through the dynamic modulation of mitochondrial function, motility, and distribution. Past and present proteomics analysis revealed the presence of O-GlcNAc-modified mitochondrial proteins in different rodents’ organs (e.g., brain) supporting that the overexpression of OGT or OGA proteins alters mitochondrial proteome and severely affects mitochondrial morphology and metabolic processes [44,45,46]. Further, hyperglycemia was associated with the aberrant O-GlcNAcylation of mitochondrial protein and with the modulation of the electron transport chain activity, oxygen consumption rate, ATP production, and calcium uptake in cardiac myocytes [44,47,48]. Thus, aberrant protein O-GlcNAcylation and its regulation of mitochondrial proteins might represent the missing link between metabolic defects and neurodegeneration occurring in T2DM and AD. Therefore, the present study aimed to decipher the role of O-GlcNAcylation and associated mitochondrial abnormalities in mediating the development of AD signatures in HFD mice by exploring how nutrient excess leads to the alteration of both OGT/OGA cycle and of energy consumption/production, thus promoting the development of AD hallmarks.

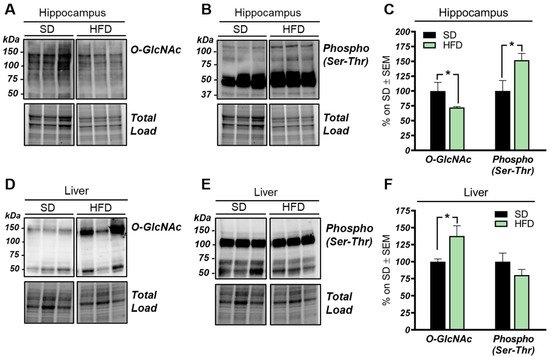

2. HFD Mice Show an Aberrant and Tissue-Specific O-GlcNAcylation Profile

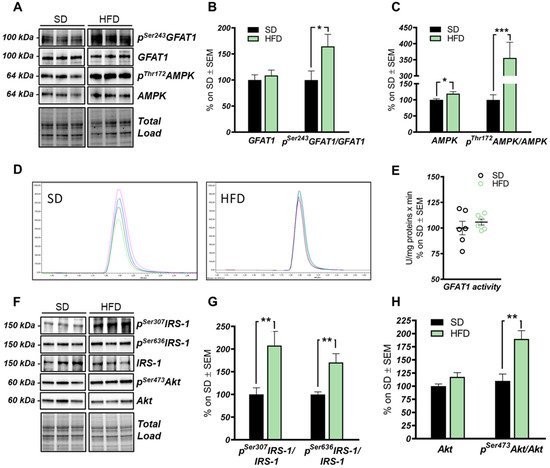

3. The HBP Flux Is Impaired in HFD Mice Compared to SD

The HBP pathway integrates multiple metabolic pathways into the synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc, providing feedback on overall cellular energy levels and nutrient availability [60]. In this scenario, increased flux of metabolites into the HBP have already been highlighted as a key point driving metabolic alterations in the skeletal muscle of a model of fat-induced insulin resistance [61]. GFAT1 is the rate-limiting enzyme that coordinates nutrients’ entrance into the HBP flux, and it is negatively regulated by AMPK upon its activation [62,63]. The analysis of the HFD hippocampus has demonstrated a significant increase of Ser243 inhibitory phosphorylation of GFAT1 compared to a respective control group (Figure 3A,B; * p < 0.05, SD vs. HFD: +65%). No relevant changes were observed in GFAT1 protein expression levels between the two groups (Figure 3A,B). In line with these data, HFD mice showed the increase of AMPK-activating phosphorylation on Thr172 compared to animals that have been fed with a SD (Figure 3A,C; *** p < 0.001, SD vs. HFD: +255%), together with a significant increase in AMPK protein levels in HFD mice (Figure 3A,C; * p < 0.05, SD vs. HFD: +20%). AMPK is known to inhibit GFAT1 activity under nutrient depletion or stress conditions via its phosphorylation on Ser243, in order to reduce the amount of nutrients entering the HBP flux [62,63,64]. Interestingly, by testing GFAT1’s ability to synthetize glucosamine-6-phosphate in vitro by HPLC, we did not observe significant changes between HFD hippocampal extract and respective SD controls (Figure 3D,E). Since the GFAT1 activity assay was carried out in a large excess of substrates [65], the reduced GFAT1 activation (measured as increased pSer243GFAT1/GFAT1 levels) may result from reduced substrate availability in the intracellular environment. These findings suggest that HFD may lead to the reduction of nutrient uptake (i.e., glucose) in the brain, promoting AMPK-mediated inhibition of GFAT1, finally resulting in reduced synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc through the HBP and decreased protein O-GlcNAcylation in the hippocampus of HFD mice. The reduction of brain insulin sensitivity is one of the most well-known causes of HFD-induced cognitive decline. Thus, we tested the hypothesis that insulin resistance could favor nutrient depletion and that AMPK-mediated inhibition of GFAT1 mice might be associated with the development of brain insulin resistance.

In detail, we observed an increase of IRS-1 phosphorylation on its inhibitory sites (Ser307 and 636) [66,67] in the hippocampus of HFD mice in comparison to standard-fed animals (Figure 3F,G; ** p < 0.01, SD vs. HFD: +108% and +70%). Furthermore, a substantial increase in pSer473Akt levels was detected in the hippocampus of the model examined compared to the control group (Figure 3F,H; ** p < 0.01, SD vs. HFD: +73%) without affecting Akt protein expression levels between the two groups (Figure 3F,H). These data show an alteration of the insulin signaling pathway, characterized by the uncoupling between IRS1 and Akt, in agreement with previous studies [6,14,66,67].

4. Discussion

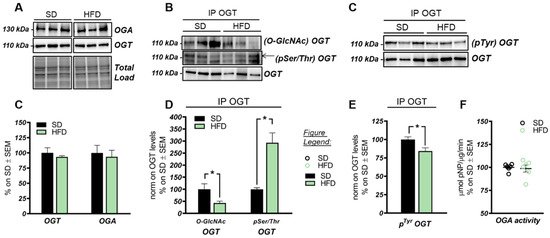

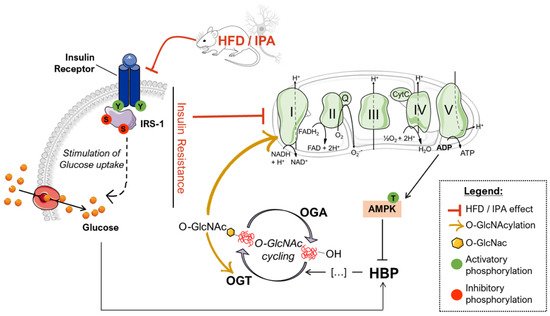

Studies on the high-fat-diet (HFD) model have largely demonstrated a strong correlation between the consumption of an hypercaloric diet and consequent alterations in brain functionality [75,76,77,78]. However, the exact molecular mechanisms that link perturbations of peripheral metabolism with brain alterations driving cognitive decline are still under discussion. Protein O-GlcNAcylation is a post-translational modification of quite recent discovery that is extremely sensitive to nutrient fluctuations, thus it has been widely recognized as a key linkage between nutrient sensing, energy metabolism, and cellular functions [79,80]. Several lines of evidence have emphasized the role of aberrantly increased protein O-GlcNAcylation in driving glucose toxicity and chronic hyperglycemia-induced insulin resistance [56,60], major hallmarks of T2DM and obesity. In this regard, the HFD model closely recapitulates molecular changes occurring in the so-called metabolic syndrome, which manifests as hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance and precedes obesity and T2DM [52,81,82]. Our analysis of liver samples from HFD mice summarized the increase in protein O-GlcNAcylation already observed in the peripheral organs of diabetic individuals, confirming O-GlcNAcylation as a major trigger of glucose toxicity [56,83,84]. A completely different scenario is to be considered for the role of O-GlcNAcylation in the brain. A wide range of evidence has already demonstrated how a hypercaloric diet affects cognitive performances, promoting metabolic dysregulation in the brain in a way similar to diabetes [75,81,85,86]. In agreement, epidemiological and molecular studies have suggested that T2DM, obesity, and general defects in brain glucose metabolism predispose to poorer cognitive performance and rapid cognitive decline during ageing, favoring the onset of dementia [40,87,88]. In this scenario, the alteration of protein O-GlcNAcylation that we observed in the hippocampus from HFD mice, coupled with the aberrant increase in Ser/Thr phosphorylation levels, resemble the alterations observed in the brain of AD individuals [31,36,89,90,91], as well as, of AD and DS mouse models. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated the reduction of total protein O-GlcNAc levels in the brain from AD and DS mice, supporting its involvement in the early molecular mechanisms promoting the development of AD signatures [22,55,92]. In line with these reports, the analysis of rat brains fed a short-term HFD demonstrated the increase of Aβ deposition and p-tau, and decreased synaptic plasticity, suggesting that molecular mechanism underling the onset of cognitive decline in HFD mice may resemble those occurring in AD models [93]. Our current investigation of tau and APP PTMs show that the alteration of their O-GlcNAcylation/phosphorylation ratio may represent one of the molecular mechanisms involved in HFD-related neurodegeneration. In particular, the significant reduction of tau O-GlcNAcylation levels, associated with the pathological increase in Ser404 phosphorylation, suggest a contrition of reduced O-GlcNAc levels in promoting tau toxicity [94,95]. As well, decreased O-GlcNAc levels of APP was shown to favor amyloidogenic processing and Aβ deposition through the increase of APP phosphorylation [96,97], however no altered levels of APP phosphorylation were observed in our study, as well as no accumulation of soluble Aβ 1–42. Although most of the pathological alterations observed in HFD mice are similar to those of other neurodegeneration models, the mechanisms underlying disturbances of O-GlcNAc homeostasis in the brain of HFD mice have different origins. We previously observed in the hippocampus of a mouse model of DS, the hyperactivation of OGA [55], but HFD mice did not show any significant increase in the removal of O-GlcNAc moiety. Rather the attention must be focused on the observed alteration of the hippocampal metabolic status associated with the development of insulin resistance. Previous human and rodent data support diet-induced insulin resistance as one of the main mediators of cognitive deficit associated with high fat consumption [68,82,93]. In agreement, mice fed with a HFD exhibited a significant increase in obesity and lower glucose and insulin tolerance as compared to animals fed with a standard diet. These changes parallel the consistent alterations of the insulin signaling in the brain characterized by increased IRS1 inhibition and the uncoupling with Akt [68,82]. These molecular events are key features of brain insulin resistance [6,66,67,74] (Figure 9). Indeed, as previously reported in HFD-treated mice, hyperactive Akt fails to further respond to insulin administration because of IRS-1 inhibition [14]. Interestingly, inhibitory serine residues of IRS1 can also be O-GlcNAcylated [22,98] leading to the possibility of reduced O-GlcNAcylation as one of the leading causes for IRS-1 hyperphosphorylation on inhibitory sites. Although it seems clear that the disruption of the balance between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation contributes to the unproper functioning of the insulin cascade, it should also be considered that the onset of insulin resistance might affect O-GlcNAc homeostasis by altering the number of metabolites available for the synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc. In line with a metabolic profile characterized by low nutrient availability and increased AMP/ATP ratio, HFD mice showed a significant increase in AMPK activation (increased pThr172AMPK levels). Most interestingly, AMPK-mediated inhibition of GFAT1 activity by its direct phosphorylation on Ser243 appears as one of the best-characterized mechanisms to reduce the amount of metabolites entering the HBP flux under nutrient depletion conditions [62,63,64], matching the changes observed in HFD mice brains (Figure 9). OGT is known to be phosphorylated by AMPK on Thr444, regulating both OGT selectivity and nuclear localization. Furthermore, the regulation of OGT expression and O-GlcNAc levels by AMPK seems to be highly dependent on cell type and pathological status, and glucose-deprivation was proven to favor OGT cytosolic localization upon AMPK activation [58,99,100,101]. Within this context, AMPK subunits have been shown to be dynamically modified by O-GlcNAc, which regulates their activation, showing a complex interplay between these enzymes [99]. Most interestingly, OGT O-GlcNAcylation/phosphorylation ratio was unbalanced in the hippocampus of HFD mice, suggesting the alteration of OGT function. Besides, the observed reduction of OGT phosphorylation on Tyr residues further supports the impairment of its activity, as suggested by Hart et al. [59]. According to this evidence, HFD-driven alterations of protein O-GlcNAcylation seems to be linked to reduced HBP flux and altered OGT PTMs, which contributes to aberrant O-GlcNAc cycling. In parallel to insulin resistance, HFD rodents also show altered mitochondrial functionality, oxidative stress, and reduced brain cortex bioenergetic [71,77,102]. In agreement, among the possible mechanisms by which nutrient overload exerts negative effects within the brain, the alteration of mitochondrial functionalities is among the most impactful. In a recent study, Chen et al. have shown an impaired expression of protein involved in mitochondrial dynamics, reduced Complex I–III activity and decreased mitochondrial respiration in HFD-treated rats [71]. Furthermore, a reduced AMP/ATP ratio in HFD rats demonstrated how diet-induced impairment of mitochondrial activity is reflected by the reduced ability to synthetize ATP as a source of energy [71]. In this scenario, data collected in the hippocampus of HFD mice are in line with recent studies on the topic, supporting that high fat consumption can affect mitochondria functionality, thus resulting in reduced respiratory capacity, decreased oxygen consumption, and reduced ATP production [77,102]. Indeed, we demonstrated in HFD mice, a significant reduction of both the expression levels and the activity of most respiratory chain complexes, especially Complex I, finally resulting in impaired ATP content in comparison to SD mice (Figure 9).

Within this context, sustained alterations in O-GlcNAcylation either by pharmacological or genetic manipulation are known to reprogram mitochondrial function and may underlie reduced cellular respiration and ROS generation [103]. Furthermore, marked reduction of global O-GlcNAcylation strongly correlates with hampered bioenergetic function and disrupted mitochondrial network in AD models, while TMG-mediated restoration of overall O-GlcNAcylation has shown neuroprotective effects [36]. Mitochondria dysfunction is a hallmark of physiological and pathological brain ageing, which may prelude to impairment of synaptic activity and depletion of synapse. However, six-week HFD protocol did not affect the expression of pre- and postsynaptic proteins, suggesting that alteration of nutrient-dependent signaling and metabolic activity in neurons may anticipate the synaptic plasticity and structural plasticity deficits observed in experimental models of metabolic disease [104,105]. Intriguingly, we also highlighted that the impairment of the Complex I could be associated with the reduced O-GlcNAcylated levels of its subunit NDUFB8, as described elsewhere [46,47,72], thus describing a pivotal role for altered protein O-GlcNAcylation in triggering mitochondrial defects mediated by high-fat consumption (Figure 9).

In agreement with data collected in HFD, the administration of IPA for 24 h to SHSY-5Y neuroblastoma cells was able to induce insulin resistance, as previously observed in primary neurons [14], which translated into the lowered activity or readaptation of the glycolytic machinery and into the reduced mitochondrial respiratory potential in response to insulin stimulation. Intriguingly, as observed in HFD mice, IPA-induced insulin resistance and metabolic changes, after IPA treatment, were associated and self-sustained by total and Complex I-specific reduction of protein O-GlcNAcylation in neuronal-like cells, confirming the crucial role of such PTMs as sensor and mediator of energetic fluctuations.

Overall, our data suggest that a diet rich in fat is associated with insulin resistance and altered metabolism of the brain, which translates into reduced protein O-GlcNAcylation and mitochondrial dysfunction. In particular, HFD-related aberrant protein O-GlcNAcylation seems to have a double role in promoting neurodegeneration, by triggering the hyperphosphorylation of tau and by reducing complex I activity.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22073746