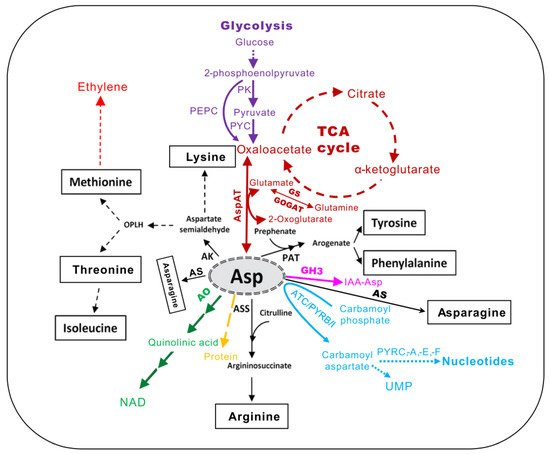

L-aspartate (Asp) serves as a central building block, in addition to being a constituent of proteins, for many metabolic processes in most organisms, such as biosynthesis of other amino acids, nucleotides, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and glycolysis pathway intermediates, and hormones, which are vital for growth and defense.

- aspartate

- stress

- aspartate aminotransferase

- aspartate transporter/carrier

- compartmentation

- hormone

1. Introduction

l-aspartate (Asp), in addition to constituting proteins and being an active residue in many enzymes, is a precursor leading to the biosynthesis of multiple biomolecules required for plant growth and defense, such as nucleotides, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), organic acids, amino acids, and their derived metabolites. Though it cannot be simply quantified, given that in Escherichia coli, approximately 27% of nitrogen flows through Asp (https://MetaCyc.org, accessed on 30 January 2021) [1], the contribution of Asp to plants is highly conspicuous. It has been well documented that methionine (Met), threonine (Thr), lysine (Lys), and isoleucine (Ile), of the eight essential amino acids, are derived from Asp, through a pathway commonly known as the Asp family amino acids [2]. Further metamorphosis of Asp can yield glutamate (Glu) to glutamine (Gln) through the action of glutamine synthetase (GS). Asp and Glu, along with asparagine (Asn) and Gln, are the common nitrogen carriers [3], which have been noted for their primary role in the recycling, storage, and transport of nitrogen in germinating seeds, vegetative organs, and senescence organs [4]. Asp is also involved in the biosynthesis of some other amino acids such as arginine (Arg) and the aromatic amino acids (tyrosine (Tyr) and phenylalanine (Phe)), through the aspartate–argininosuccinate synthase and the aspartate–prephenate aminotransferase pathways, respectively [5]. Moreover, Asp is the building block for de novo pyrimidine manufacturing and is required to convert ionosine-5′-monophosphate to adenine-5′-monophosphate in purine biosynthesis [6]. In addition, Asp serves as a critical precursor of the aspartate oxidase pathway in the synthesis of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), an essential component of plant abiotic process, senescence, chlorophyll formation, and pollen development [7,8,9]. In addition, Asp deamination to oxaloacetate by aspartate aminotransferase (AspAT) in the cytosol is essential for the production of malate needed in mitochondria for the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle [10], whereas Asp released from the mitochondrion is involved in the biosynthesis of nucleotides in the cytosol. Intriguingly, some recent studies have found that cytosolic Asp is an endogenous metabolic limiter of cell proliferation [6,11,12,13,14,15], moreover, Asp derived from glucose is indispensable to drive biomass synthesis during cellular hypertrophy [16]. Altogether, apparently, Asp represents a critical metabolite hub interconnecting with diverse metabolic pathways that are of significant importance for plant nutrition, energy, and stress responses.

Exchange and competition for Asp and derived intermediates profoundly affect plant metabolism, which requires great attention. The detailed study and research into anabolism and catabolism of Asp and its related pathways (i.e., the Asp family amino acids, nucleotides, NAD, TCA, and glycolysis) are thus necessary to increase our knowledge on cell growth and repair [17], so as to further our understanding of plant growth, development and defense [13,15,18]. Herein, the various pathways derived from Asp are summarized in this review (Figure 1), and a general overview of Asp metabolism and regulation is described. In addition, the dynamism of Asp and AspAT in plants and their role in the plant in response to various stress conditions are discussed. Furthermore, some recent progress in the interconnection between Asp and phytohormones, such as ethylene and auxin, is highlighted.

Figure 1. The central metabolic intermediates derived from l-aspartate (Asp) in plants (adapted from [5]). AK, aspartate kinase; AO, aspartate oxidase; ASS, argininosuccinate synthase; AS, asparagine synthase; PAT, prephenate aminotransferase; AspAT, aspartate aminotransferase; GS, glutamine synthetase; GOGAT, glutamine oxoglutarate aminotransferase; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; PK, pyruvate kinase; PYC, pyruvate carboxylase; PEPC, phosphoenolpyruvate carbosylase; ATC/PYRB/I, aspartate transcarbamoylase or aspartate carbamoyl transferase; PYRC, dihydro-orotase; PYDA, dihydro-orotate dehydrogenase; PYRE, phosphoribosyl transferase; PYRF, orotate decarboxylase. GH3, group II of GRETCHEN HAGEN3 family of acyl amido synthetases.

2. Role of Asp in Growth and Stresses

2.1. Asp is an Endogenous Metabolic Limitation for Cell Proliferation

Cytosolic Asp has profound importance to the proliferating cells, as it determines the cell’s survival, especially when Gln is limited [13]. The drop in cytosolic Asp resulting from the knockdown of aspartate–glutamate carrier 1 (AGC1, known as ARALAR) leads to the reduction of the proliferation of several cell lines [15]. On the contrary, the supply of exogenous Asp or overexpression of an Asp transporter can bypass the need for an electron transport chain to support cell proliferation [6], demonstrating that Asp biosynthesis is a golden requirement for cell proliferation [13]. This has been further confirmed by the finding that TCA can only fully restore cell growth if it partners with Asp biosynthesis, thus, when AspAT is activated [15]. Further DNA content analysis by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry reveals that the requirement of Asp for cell growth is at least partially because it sustains nucleotide biosynthesis [11,13].

2.2. Asp in Plants Coordinates Nitrogen Assimilation into Amino Acids

Asp and Glu and their amides make up more than one-third of the free amino acids in Arabidopsis [3]. They link the in vivo metabolism of amino acids to the relevant organic acids in the TCA cycle and the carbon metabolism in the glycolysis pathway [67,68]. When carbon skeletons are limited, Asp is amidated to form Asn, which serves as an efficient nitrogen transport and storage compound due to its relatively high N:C ratio (2:4) [69,70]. Under nitrogen stress, Asp appears to be one of the most importantamino acids [71,72,73,74,75]. It has been found that when N is sufficient, as a predominant amino acid translocated in plant phloem, Asp supplied by the phloem is converted in the root to Asn to export N to the shoot via xylem as part of the process of nitrogen assimilation, whereas, when N is absent, Asp supplied by the phloem is diverted to the formation of malate to support the metabolism cycle back to the shoot [74]. In a very recent study, higher Asp and Asn contents were observed to be positively coordinated with the nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) trait in potatoes with low N supply [75]. The above results suggest that Asp is imperative for amino acid and organic acid biosynthesis, especially under fluctuating N conditions. Asp coordinates nitrogen assimilation into amino acids such that the available carbon skeleton is mobilized [27,76]. Further targeted regulation of Asp metabolism might be a useful strategy to improve the NUE traits in plants.

2.3. Asp is a Drought Stress-Specific Responsive Metabolite

One of the most critical processes that affects plants under drought conditions is the accumulation of solutes, including amino acids in the leaf tissues and the roots. Asp concentration was recorded to increase by more than twofold in drought treatment in Brassica napus [77], Astragalus membranaceus [78], and Triticeae [79]. Similarly, Asp has shown the second-highest concentration (the second most activated compound) after ABA in root exudates of the holm oak (Quercus ilex) upon drought treatment [80]. Additionally, in chickpea plants treated with a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium (PGPR) and plant growth regulator (PGRs) consortium and grown under drought stress conditions, a higher accumulation of Asp in the leaf of the tolerant variety was recorded as compared to the sensitive variety [81]. In addition, a significant change of Asp has been recorded in kale [82] and Caragana korshinskii [83], though its content declined upon drought stress. Regardless, the great range of variation of Asp content upon drought exposure suggests that Asp can serve as a drought-responsive biomarker.

2.4. The Variation of Asp Level Is Closely Linked to Stress Acclimation

When exposed to stress, plants accumulate a multitude of metabolites, particularly amino acids. A line of studies suggest a close correlation between the variation of Asp content and plant stress [84]. For example, under alkaline salt stress, a significant increase (3.97-fold) in Asp and other metabolites, such as proline (Pro), Glu, serine (Ser), and alanine (Ala), in wild soybean seedlings compared to semi-wild and cultivated soybean has been observed [85]. In response to 250 mM NaCl salt stress, the level of Asp increased by 11-fold in the root and about 6.2-fold in the shoot of Aeluropus lagopoides [86]. Under the same conditions, Asn, Lys, glycine (Gly), and Pro increased by 1.46- to 9.98-fold in the shoot, while in the root, Gly, Pro, Phe, and ethanolamine increased by approximately 2.5- to 15.6-fold. NaCl-treated wheat seedlings showed a 15.75-fold increase in Asp, and a 1.6-fold increase in total free amino acids compared to the control. Likewise, there was a significant enhancement (2.7-fold) of Asp after plants were inoculated with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens RWL-1 under salinity stress conditions [87]. The high accumulation of Asp and other amino acids, such as Pro under salt stress, has played an essential role in plants in highly saline conditions by maintaining the intracellular osmotic potential and stabilizing membrane proteins [88]. Furthermore, the change of Asp content has been reported to be coupled with the alteration of protein metabolism in salt-stressed plants [89].

In the same manner, the response of Asp to cold stress has been observed. For instance, the level of Asp together with Pro and putrescine increased rapidly in leaves of strawberry during cold (2 °C) acclimation processes [90]. In fig fruits during cold storage, the contents of Asp, as well as Glu, were upregulated, while the level of most other free amino acids decreased [91]. A heatmap matrix of a Pearson’s correlation coefficient test reveals that the enhancement of Asp and Glu is positively correlated to water loss, glucose, and fructose variables [91]. Likewise, the Asp content in rye substantially responded to cold hardening. A larger amount of Asp was found in the variety with higher frost tolerant ability, especially in the early phases of cold acclimation. The contents of Asp, Pro, Tyr, and glycine betaine were observed to linearly increase in response to overwintering (cold stress) [92]. In addition, a greater accumulation of Asp, Glu, and β-alanine in leaves, concomitant with an enhancement of raffinose and 1-kestose in roots of wheat, has been demonstrated to be associated with the improvement of phosphorus use efficiency (PUE) in P-efficient wheat cultivars under low P supply [93]. These results clearly show the active response and co-regulation activity of Asp and coupled amino acids, sugars, and organic acids to stresses, suggesting that modulation of metabolite flux from Asp is likely beneficial for plant stress adaption, as it provides the plant with essential metabolism substances and energy.

Oxidative stress is a common consequence for plants exposed to non-optimal environmental conditions. To cope with oxidative stress, plants employ the redox buffer system, scavenging enzymes, and metabolic mechanisms to detoxify reactive oxygen species (ROS) [94,95]. It has been found that the amounts of Asp, as with malate, 2-OG, Glu, and hexose phosphates, were decreased in Arabidopsis roots treated with menadione to elicit oxidative stress. On the contrary, these compounds increased and returned back to the control levels following the removal of menadione [96]. The reactive and recovery responses of Asp and derived compounds to oxidative stress are thought to be pivotal for reconfiguring the metabolic network to help plants recover and survive [97].

2.5. Asp Acts as a Biomarker of Biotic Stress and Environment-Induced Exposure

As biochemically active compounds, free amino acids strongly respond to increased amounts of toxic substances in the environment [84]. In agreement with this, the free amino acid content increased in tomato plants grown in soil contaminated with arsenate (As(V)). Among these free amino acids, Asp and Glu were intensively accumulated [98]. The content of Asp was significantly reduced in aluminum (Al)-treated citrus roots, although most of the amino acids, as well as some sugars (i.e., raffinose and trehalose), were increased [99]. Asp, together with other amino acids relating to nitrogen metabolism, showed high accumulation in response to the arbuscular colonization of Medicago truncatula Gaertn. cv. Jemalong (A17) [100]. The level of Asp concentration was reported to be elevated in the root, stem, and leaf tissue of Fusarium wilt-symptomatic watermelon compared to the asymptomatic plants. As a consequence, it promotes the growth and development of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum. [101]. In addition, a higher concentration of Asp was detected in tomato seedlings grown from seeds primed with 100 nM jasmonic acid (JA) treatments under nematode infection, displaying the vital role of Asp in the fight against nematodes during JA treatment in tomatoes [102]. However, disease suppression of Fusarium crown rot showed a positive change of Asp in mycorrhizal asparagus, indicating the possible implication of Asp in Fusarium infection [103].

Taken together, notable stress-related responses of Asp to variable environmental exposures in plants have been observed, indicating an essential role of Asp in response to stress (Table 1). Since Asp is a key precursor for the biosynthesis of many fundamental metabolites, it can be reasonably inferred that the change of concentration of Asp fine-tunes the availability of downstream metabolites that are indispensable for plants to grow and to counteract various stresses. For instance, it fine-tunes central metabolism with glycolysis (sucrose, hexose, pyruvate, etc.), the citric acid cycle (2-OG, succinate, etc.), NAD, and nucleotides to support cell survival [9,11,78,79,83,90,91,96]; the essential amino acids Met, Lys, Thr, Ile, and other amino acids to adjust the total amino acid pool and protein metabolism [89,104]; and the organic N carriers Glu, Asn, and Gln to regulate N mobilization, storage, and recycling [71,72,105,106,107]. In addition, alteration of Asp levels can also be linked with malate activity as a consequence of stomatal opening, Ca2+ uptake inhibition, and amino acid transformation [74,86]. In addition, increasing Asp concentration in plants during anaerobic stress decreases the cytoplasmic pH, which affects the production of other intracellular metabolites, such as alanine and GABA [108].

| Stress | Species | Tissues (Stress Period) | Asp Fold Change | Change of Asp-Associated Metabolites | Physiological Role | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drought | Astragalus membranaceus | Roots (10 days) | 2.3 | ↑Asp family metabolism, ↑glutamate, ↑GABA,↑TCA cycle, ↑sucrose | Sensing water status | [78] |

| Cicer arietinum L. (chickpea) | Leaves | −2.5~−6.1 | ↑Thr, ↑Met, ↓Asn, ↑citrulline | Osmoregulation | [81] | |

| Caragana korshinskii | Leaves and roots | −0.32~−0.63 | ↑Asn, ↑sugars/glycosides, ↓Glu,↓isocitric acid | Drought-responsive metabolites | [83] | |

| Triticeae | Roots and leaves | >2 | ↑Succinate, ↑Trehalose, ↑Glu, ↑Asn, ↑Met, ↑Phe | Drought stress-specific responsive metabolites | [79] | |

| Brassica oleracea L. var. acephala (kale) | Leaves | −1.3 | ↓Glu, ↓Thr, ↓Ala, ↑Pro | Biomarker for drought tolerance | [82] | |

| Salinity | Aeluropus lagopoides | Shoots and roots | 6.2~11 | ↑Asn, ↑Lys, ↓malate | Stomatal opening, inhibited Ca2+ uptake | [86] |

| Wheat | Seedlings (17 days) | 15.75 | ↑Ile, ↑Lys, ↑Phe, ↑Pro, ↓Glu, ↓Arg, ↓Met | Protein metabolism, osmoprotection | [89] | |

| N starvation or low N | Non- nodulated soybean | Phloem sap (4 days) | −3.7 | ↓Asn, ↓Glu, ↑malate, ↑GABA | Transform to malate to deliver the amino acids | [74] |

| Maize | Leaves | ≈2 | ↓Asn, ↓Glu | Regulation of N mobilization | [72] | |

| Solanum tuberosum L. (potato) | Shoots and tubers of potato cv. Kufri Jyoti | >5 | ↑Thr, ↑Asn, ↑Glu, | NUE efficiency | [75] | |

| Tobacco | Leaves | >−2 | ↑Glu, ↑Lys, ↑Ile, ↓Gln, ↓Arg, ↓Phe | Represents a significant proportion of the total amino acid pool | [104] | |

| Soybean | Xylem sap | ≈8 | ↓Asn, ↓Gln, ↑Glu, ↑Ala, ↑GABA | N recycling, source of N in alanine formation | [71] | |

| Supplementation of nitrate | Soybean | Roots | ≈3 | ↑Asn, ↑Glu, ↑Gln | Provide C skeleton for the synthesis of Asn | [105] |

| Low C | Tobacco | Leaves | >−2 | ↑Glu, ↑Asn, ↓Phe | Represents a significant proportion of the total amino acid pool | [104] |

| Light | Sunflower | Leaf discus | ≈2 | ↑Glu, ↑Gln | Convert to Asn for N storage and transport in the dark | [106] |

| Tobacco | Leaves | 2.6 | ↑Phe | Light-responsive marker metabolites | [104] | |

| Cold | Fragaria × ananassa (strawberry) | Leaves and roots of Duch. “Korona” | 3–5 | ↑Ile, ↑hexoses, ↑pentoses | Protective metabolites | [90] |

| Secale cereale (rye) | Plant crown | 3 | ↑Glu, ↑Pro | Frost tolerance improvement | [92] | |

| Ficus carica L. (fig) | Fruits | >2 | ↑Glu, ↑Glucose, ↑fructose, ↓Arg, ↓GABA, ↓Phe, ↓Ile, ↓Pro | Cold-responsive marker metabolites | [91] | |

| Low P | Triticum aestivum L. (Wheat) | Leaves | 1.2 | ↑Gln, ↑β-alanine, ↑raffinose, ↑1-kestose | Enhanced PUE | [93] |

| Fusarium wilt | Citrullus vulgaris (watermelon) | Leaves, stems, and roots | 33–43 | ↑Lys, ↑Arg, ↑citrulline | Biomarker of Fusarium wilt disease | [101] |

| Fusarium crown rot | Asparagus officinalis L., cv. “Welcome” | Mycorrhizal asparagus shoots | ≈1.7 | ↑Glu, ↑Arg, ↑citrulline, ↑GABA | Disease tolerance | [103] |

| Parasitic weed | Faba bean | Tubercles of tolerant line | ≈−0.4 | ↓Asn, ↓Glu, ↓Gln, ↓GABA,↓sucrose | N metabolism of the parasite | [107] |

| Arbuscule | Medicago truncatula | Mycorrhizal roots | >10 | ↑Glu, ↑Asn, ↑Gln, ↑sucrose, ↑trehalose | Associated with higher N availability | [100] |

| JA (100 nM) | Tomato | Seedlings | 1.6 | ↑Asn, ↑Glu, ↓Gln,↓Lys, ↓Met,↓Arg | Osmoregulation | [102] |

| Oxidative stress | Arabidopsis thaliana | Roots (6 h) | ≈2 | ↓Glu, ↓malate, ↓succinate, ↓fumarate, ↓hexose phosphates, ↑2-OG, ↑pyruvate, ↑citrate | Oxidative stress-responsive metabolites | [96] |

| Hypoxia | Muskmelon | Roots (6 days) | 1.23 | ↑Thr, ↑Glu, ↑Lys, ↑GABA | Hypoxia-responsive metabolites | [109] |

| Anoxia | Rice | Excised roots | ≈−2 | ↑GABA, ↑Pro, ↑pyruvate,↓Glu,↓Gln, ↓Asn, ↓2-OG | Corresponds to a weak fall in cytoplasmic pH | [108] |

| Arsenate (As(V)) | Tomato | Aboveground tissues and roots | 2.4–3.1 | ↑Asn, ↑Gln, ↑Glu, ↑Arg, ↑Lys, ↑Ile | Marker for As(V) stress | [98] |

| Aluminum (Al) | Trifoliate orange | Roots | −2 | ↓Ile, ↓Glu, ↓malate,↓sugars, ↑Asn, ↑Lys, ↑Gln | Marker for Al stress | [99] |

↑, upregulation; ↓, downregulation; Asp, aspartate; Glu, glutamate; Gln, glutamine; Arg, arginine; Ile, isoleucine; Pro, proline; 2-OG, 2-oxoglutarate; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; JA, jasmonic acid.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules26071887