This scoping review aimed to explore the characteristics, strengths, and gaps in research conducted in Brazilian long-term care facilities (LTCFs) for older adults. Electronic searches investigating the residents (≥60 years old), their families, and the LTCF workforce in Brazil were conducted in Medline, EMBASE, LILACS, and Google Scholar, within the timescale of 1999 to 2018, limited to English, Portuguese, or Spanish. The reference lists were hand searched for additional papers. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used for critical appraisal of evidence. Data were reported descriptively considering the study design, using content analysis: 327 studies were included (n = 159 quantitative non-randomized, n = 82 quantitative descriptive, n = 67 qualitative, n = 11 mixed methods, n = 6 randomized controlled trials, and n = 2 translation of assessment tools). Regardless of the study design, most were conducted in a single LTCF (45.8%), in urban locations (84.3%), and in non-profit settings (38.7%). The randomized trials and descriptive studies presented the lowest methodological quality based on the MMAT. This is the first review to provide an overview of research on LTCFs for older people in Brazil. It illustrates an excess of small-scale, predominantly qualitative papers, many of which are reported in ways that do not allow the quality of the work to be assured.

- older adults

- care homes

- nursing homes

- long-term care

- older people

- scoping review

1. Introduction

The fast growth of the older population in low- and middle-income countries [1] has allowed little time for social and health care systems to adapt. Long-term care facilities (LTCFs) are an integral part of how such systems care for older people with frailty, particularly as health conditions become more complex over time and they are no longer able to be cared for at home.

The sustainability of the LTCF sector depends upon policy and economic decisions [2]. In Brazil, where aggregate levels of wealth are lower and welfare systems are underdeveloped, the financial burden of aging is predominantly borne by families or older individuals themselves, leading to precarity of funding and lack of investment to enable development of the sector [3][4][5][6].

In 2010, there were around 3500 registered LTCFs in Brazil, and around 100,000 older people (aged 60 years and older) were living in such facilities, making the sector much smaller than in many middle- and higher-income countries [6][7]. However, estimations of the size of the sector are impaired by a lack of systems for collecting and sharing national data on LTCFs [8]. This lack of information is, in turn, a hindrance to the development of the Brazilian LTCF sector.

Research on LTCFs is an emerging field in low- and middle-income countries [9][10]. In Brazil, it has not been supported or funded in a strategic way [7][11]. This lack of co-ordination means that we are, as yet, unclear about the extent, quality, and impact of research in the sector or how it impacts on older adults’ care [7][11]. Taking stock of research carried out to date in Brazilian LTCFs will provide an understanding of the current state of the art of research in this area and highlight where work is needed.

This scoping review (SR) set out to provide an overview of the nature and extent of the scientific research conducted in Brazilian LTCFs in order to provide a summary for care providers and policymakers to inform the future endeavors in the field. The purpose of this is to give researchers, policymakers, and those commissioning research in Brazil a “big picture” overview of long-term care research conducted in Brazil over the past two decades. This overview can be used to design a coordinated plan of action for future research as well as linking to international expertise where appropriate.

We asked the following question: “What are the general features of, and gaps in, empirical research conducted across Brazilian LTCFs for those aged over 60 years?”

Our objectives were to:

-

Describe the type and quality of empirical research conducted in Brazilian LTCFs for those aged over 60 years;

-

Identify the topic areas of published research;

-

Map the regions in Brazil where this research was conducted;

-

Identify current knowledge gaps.

2. Study Inclusion

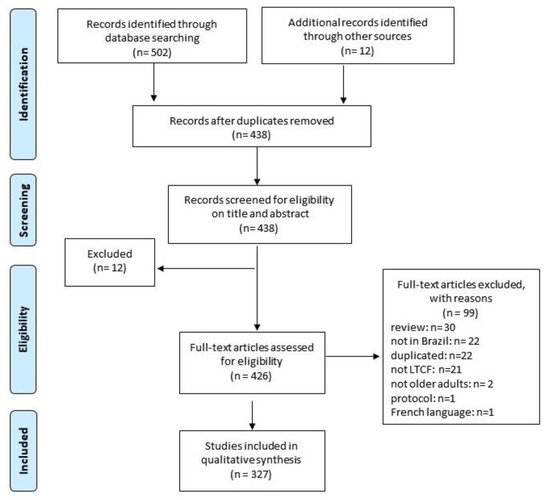

A total of 512 publications were retrieved. A further 12 articles were identified during the secondary screening of the references. After deleting duplicates, 438 studies were assessed for eligibility. Ninety-nine papers were excluded, yielding 327 studies that were included. Figure 1 shows a PRISMA diagram summarizing the study selection process.

Figure 1. Flow chart with scoping review selection process.

3. Features of Included Studies

Table 1 presents an overview of the included studies. Two studies are not included in the tables as they did not fit any of the designs listed on the MMAT (translation/cultural adaptation of assessment tools). Quantitative non-randomized research (QNR) (for example, non-randomized controlled trials, cohort and case–control studies, and cross-sectional analytic studies) comprised almost half of the included papers (n = 159; 48.9%), followed by quantitative descriptive (QD) (n = 82; 25.2%), qualitative (n = 67; 20.6%), mixed methods (n = 11; 3.4%), and randomized controlled trials (RCT) (n = 6; 1.9%).

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies regarding primary research conducted in Brazilian long-term care facilities (LTCFs) published in scientific journals by methodology.

| Qualitative (n = 67) | Descriptive (n = 82) | Non-Randomized (n = 159) | RCT (n = 6) | Mixed Methods (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication Date | |||||

| 1999–2009 | 11 (16.4%) | 19 (23.1%) | 24 (15.1%) | 1 (16.6%) | 5 (45.5%) |

| 2010–2015 | 42 (62.6%) | 45 (54.9%) | 83 (52.2%) | 1 (16.6%) | 5 (45.5%) |

| ≥2016 | 14 (20.9%) | 18 (21.9%) | 52 (32.7%) | 4 (66.8%) | 1 (9.0%) |

| Language | |||||

| English | 6 (8.9%) | 15 (18.3%) | 47 (29.5%) | 1 (16.6%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| Portuguese | 46 (68.7%) | 51 (62.2%) | 73 (45.9%) | 3 (50.0%) | 7 (63.6%) |

| At least Portuguese/English | 15 (22.4%) | 16 (19.5%) | 39 (24.6%) | 2 (33.4%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| Geographic area * | |||||

| North | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 4 (2.5%) | 0 | 0 |

| Northeast | 13 (19.4%) | 21 (25.6%) | 32 (20.1%) | 1 (16.6%) | 0 |

| South | 29 (43.2%) | 17 (20.7%) | 35 (22.0%) | 3 (50.0%) | 7 (63.6%) |

| Southeast | 14 (20.9%) | 34 (41.5%) | 65 (40.9%) | 0 | 4 (36.4%) |

| Midwest | 4 (5.9%) | 6 (7.3%) | 16 (10.0%) | 1 (16.6%) | 0 |

| ≥2 geographic area | 3 (4.5%) | 2 (2.4%) | 3 (1.9%) | 0 | 0 |

| NR | 3 (4.5%) | 2 (2.4%) | 4 (2.5%) | 1 (16.6%) | 0 |

| 1st Author Institution | |||||

| Public University | 44 (65.7%) | 59 (71.9%) | 106 (66.7%) | 4 (66.8%) | 6 (54.5%) |

| Private University | 19 (28.3%) | 17 (20.7%) | 33 (20.7%) | 2 (33.2%) | 5 (45.5%) |

| Health Service | 2 (3.0%) | 2 (2.4%) | 6 (3.8%) | 0 | 0 |

| Governmental Agency | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0 | 0 |

| Others | 2 (3.0%) | 2 (2.4%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0 | 0 |

| NR | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0 | 0 |

| Ethical approval † | |||||

| Yes | 59 (88.0%) | 64 (78.0%) | 132 (83.0%) | 5 (83.4%) | 8 (72.7%) |

| NR | 8 (12.0%) | 18 (22.0%) | 27 (17.0%) | 1 (16.6%) | 3 (27.3%) |

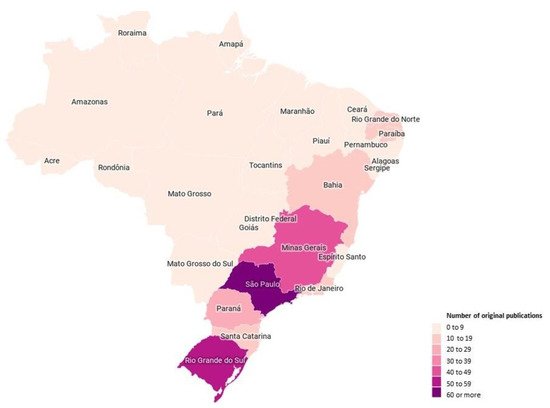

Most papers (n = 265; 81.5%) were published in the last ten years. The full text was available only in Portuguese in 180 publications (55.4%). Most articles had acceptable statements about ethical review; however, we could not locate any information on ethics procedures for 57 papers (17.5%). Figure 2 maps the Brazilian regions in which the studies were undertaken (according to first author institutional affiliation), illustrating the concentration of scientific research in the South and Southeast regions of Brazil.

Figure 2. Characterization of the number of original publications included according to the Brazilian state of the institutional affiliation of the first author.

4. Characteristics of Included LTCFs

Regardless of the study design, most were conducted in a single LTCF (n = 149; 45.8%), in urban locations (n = 274; 84.3%), and in non-profit settings (n = 126; 38.7%) (Table 2). A high proportion of studies failed to sufficiently report the type of setting and its location (37.0% and 38.5%, respectively). The main sample composition involved LTCF residents (n = 241; 74.1%) with an average of 13 older adults (2 to 59) in qualitative studies and 178 older adults (1 to 2184) in descriptive quantitative papers.

Table 2. Characteristics of the long-term care facilities (LTCFs) studied in the included papers from primary research conducted in Brazilian LTCFs published in scientific journals by the type of methodology.

| Qualitative (n = 67) | Descriptive (n = 82) | Non-Randomized (n = 159) | RCT (n = 6) | Mixed Methods (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of setting | |||||

| Profit | 2 (3.0%) | 0 | 1 (0.6%) | 0 | 0 |

| Non-profit | 32 (47.7%) | 31 (37.8%) | 59 (37.1%) | 3 (50.0%) | 1 (9.0%) |

| Both | 12 (17.9%) | 17 (20.7%) | 36 (22.6%) | 0 | 5 (45.5%) |

| NR | 21 (31.4%) | 34 (41.5%) | 63 (39.6%) | 3 (50.0%) | 5 (45.5%) |

| Setting Location | |||||

| Rural | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 (0.6%) | 0 | 0 |

| Urban | 43 (64.2%) | 42 (51.2%) | 94 (59.1%) | 2 (33.2%) | 8 (72.7%) |

| Both | 0 | 5 (6.1%) | 8 (5.0%) | 0 | 0 |

| NR | 23 (34.3%) | 35 (42.7%) | 56 (35.3%) | 4 (66.8%) | 3 (27.2%) |

| Number of LTCF | |||||

| 1 | 46 (68.7%) | 35 (42.1%) | 60 (37.7%) | 3 (50.0%) | 5 (45.5%) |

| 2–5 | 9 (13.4%) | 19 (22.9%) | 37 (23.2%) | 3 (50.0%) | 1 (9.0%) |

| 6–10 | 8 (11.9%) | 12 (15.6%) | 25 (15.7%) | 0 | 0 |

| ≥11 | 3 (4.5%) | 08 (9.7%) | 22 (13.8%) | 0 | 4 (36.5%) |

| NR/NA | 1 (1.5%) | 08 (9.7%) | 15 (9.4%) | 0 | 1 (9.0%) |

| (Min–Max, mean, median) | (0–52, 3.7, 1) | (1–156, 10.1, 2) | (1–125,6.4, 2) | (1–5, 2.0, 1.5) | (1–52, 14.4, 1) |

| Sample composition | |||||

| Older adults | 33 (49.2%) | 64 (78.0%) | 133 (83.6%) | 6 (100%) | 5 (45.5%) |

| Total (Min–Max, mean, median) | Total = 428 (2–59, 12.9, 10) |

Total = 11,358 (1–2184, 177.4, 76) |

Total = 22.747 (4–3903, 171.0, 81.0) |

Total = 164 (13–37, 27.3, 30) |

Total = 204 (8–55, 40.8, 43) |

| Family | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total (Min–Max, mean, median) | Total = 6 | ||||

| Staff | 19 (28.3%) | 7 (8.5%) | 7 (4.4%) | 0 | 3 (27.2%) |

| Total (Min–Max, mean, median) | Total = 337 (7–40, 17.7, 16) | Total = 411 (12–181, 58.7, 38.5) | Total = 459 (22–181, 65.5, 45) | Total = 281 (38–181, 93.6, 62) | |

| LTCF characteristics | 3 (4.4%) | 7 (8.5%) | 2 (1.3%) | 0 | 0 |

| Total (Min–Max, mean, median) | Total = 59 (1–52, 19.6, 6) | 199 (4–156, 28.4, 7.5) | Total = 80 (29–51, 40.0, 40) | ||

| Managers and stakeholders | 3 (4.4%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Total (Min–Max, mean, median) | Total = 18 (5–7, 6.0, 6) | Total = 67 | |||

| Older adults × Non-institutionalized older adults | 0 | 2 (2.4%) | 15 (9.4%) | 0 | 1 (9.0%) |

| Total (Min–Max, mean, median) | Total = 192 (15–177, 96.0, 96) × Total = 273 (30–243, 136.5, 136.5) | Total = 1180 (14–393, 78.7, 42) × Total = 16,839 (14–598, 112.6, 76) | Total = 30 × Total = 30 | ||

| Older adults × Staff | 2 (3.0%) | 1 (1.2%) | 2 (1.3%) | 0 | 2 (18.3%) |

| Total (Min–Max, mean, median) | Total = 13 (3–10, 6.5, 6.5) × Total = 25 (9–16, 12.5, 12.5) | Total = 62 × Total = 33 | Total = 57 (11–46, 28.5,28.5) × Total = 40 (15–25, 20.0, 20) | Total = 314 (6–308,157.0, 157) × Total = 50 (7–43, 25.0, 25.0) | |

| Older adults × Family | 1 (1.5%) | ||||

| Total (Min–Max, mean, median) | Total = 3 × Total = 3 | ||||

| Older adults × Managers | 3 (4.4%) | ||||

| Total (Min–Max, mean, median) | Total = 27 (8–11, 13.5, 8) × Total = 17 (3–7, 8.5, 7) | ||||

| Family × Staff | 1 (1.5%) | ||||

| Total (Min–Max, mean, median) | Total = 13 × Total = 19 | ||||

| Managers × Staff | 1 (1.5%) | ||||

| Total (Min–Max, mean, median) | Total = 20 × Total = 36 |

5. Research Topic Areas

The main research topics were grouped into three categories: resident outcomes (n = 266; 81.8%), staff and family support (n = 41; 12.6%), and LTCF characteristics (n = 18; 5.6%). Within the resident outcomes topic, the most frequent subtopics were functional capacity (n = 36; 13.5%), mental health (n = 30; 11.3%), and nutrition (n = 26; 9.8%). Within “staff and family support”, the main subtopics were experiences of care (n = 18; 43.9%) and work conditions (n = 4; 9.7%). Within “LTCF”, organizational context (n = 12; 66.6%) and policies (n = 6; 33.4%) were the only two subtopics. A table covering the main topic areas of research conducted in Brazilian long-term care facilities is available in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1).

6. Methodological Appraisal

Table 3 summarizes the methodological appraisal of the included articles using the MMAT. RCT and descriptive studies had a higher proportion of MMAT classified as “no” or “cannot determine” than the other designs. Therefore, the quality of the evidence based on the MMAT was lower for these designs. Studies with a qualitative design scored higher.

Table 3. Critical appraisal of included sources of evidence through the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), n = 325.

| Screening Questions (for All Types) | Qualitative (n = 67) | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Are there clear research questions? | Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? | ||||||||||||||

| Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C |

| 62 | 5 | - | 53 | 9 | 5 | 56 | 6 | 5 | 38 | 7 | 22 | 40 | 3 | 24 | 37 | 6 | 24 | 37 | 11 | 19 |

| Quantitative randomized controlled trials (n = 6) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Is randomization appropriately performed? | Are the groups comparable at baseline? | Are there complete outcome data? | Are outcome assessors blinded to the intervention provided? | Did the participants adhere to the assigned intervention? | ||||||||||||||||

| Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C |

| 6 | - | - | 5 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | - | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Quantitative non- randomized (n = 159) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Are the participants representative of the target population? | Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? | Are there complete outcome data? | Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? | During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? | ||||||||||||||||

| Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C |

| 156 | 3 | - | 140 | 6 | 13 | 57 | 47 | 55 | 120 | 19 | 20 | 126 | 7 | 26 | 56 | 58 | 45 | 120 | 15 | 24 |

| Quantitative descriptive (n = 82) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | Is the sample representative of the target population? | Are the measurements appropriate? | Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? | Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | ||||||||||||||||

| Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C |

| 78 | 3 | 1 | 64 | 11 | 7 | 37 | 21 | 24 | 32 | 31 | 19 | 61 | 9 | 12 | 29 | 12 | 41 | 58 | 8 | 16 |

| Mixed methods (n = 11) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed methods design to address the research question? | Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? | ||||||||||||||||

| Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C | Y | N | C |

| 11 | - | - | 7 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 1 |

| Category with most of the studies with YES | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Category with most of the studies with NO | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Category with most of the studies with CANNOT DETERMINE | ||||||||||||||||||||

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph18041522

References

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. Ageing and Health. 2019. Available online: (accessed on 5 February 2018).

- Pot, A.M.; Briggs, A.M.; Beard, J.R. The Sustainable Development Agenda Needs to Include Long-Term Care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 725–727.

- Beard, J.R.; Officer, A.M.; Cassels, A.K. The World Report on Ageing and Health. GERONT 2016, 56, S163–S166.

- Committee on Population; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. Future Directions for the Demography of Aging: Proceedings of a Workshop; Hayward, M.D., Majmundar, M.K., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. 25064. ISBN 978-0-309-47410-8.

- Roquete, F.F.; Batista, C.C.R.F.; Arantes, R.C.; Roquete, F.F.; Batista, C.C.R.F.; Arantes, R.C. Care and Management Demands of Long-Term Care Facilities for the Elderly in Brazil: An Integrative Review (2004–2014). Rev. Bras. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2017, 20, 286–299.

- Camarano, A.A.; Kanso, S. As instituições de longa permanência para idosos no Brasil. Rev. Bras. Estud. Popul. 2010, 27, 232–235.

- Jacinto, A.F.; Achterberg, W.; Wachholz, P.A.; Dening, T.; Harrison Dening, K.; Devi, R.; Oliveira, D.; Everink, I.; Gaiolla, P.A.; Villas Bôas, P.J.F.; et al. Using international collaborations to shape research and innovation into care homes in brazil: A white paper. J. Nurs. Home Res. Sci. 2020, 6, 109–113.

- Wachholz, P.A.; Moreira, V.G.; Oliveira, D.; Watanabe, H.A.W.; Boas, P.J.F.V. Occurrence of infection and mortality by covid-19 in care homes for older people in brazil. In Occurrence of Infection and Mortality by Covid-19 in Care Homes for Older People in Brazil; Botucatu Medical School-São Paulo State University: Botucatu, Brazil, 2020.

- Tolson, D.; Rolland, Y.; Andrieu, S.; Aquino, J.P.; Beard, J.; Benetos, A.; Berrut, G.; Coll-Planas, L.; Dong, B.; Forette, F.; et al. International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics: A Global Agenda for Clinical Research and Quality of Care in Nursing Homes. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2011, 12, 184–189.

- Shepherd, V.; Wood, F.; Hood, K. Establishing a Set of Research Priorities in Care Homes for Older People in the UK: A Modified Delphi Consensus Study with Care Home Staff. Age Ageing 2016, 46, 284–290.

- Wachholz, P.A.; Ricci, N.A.; Hinsliff-Smith, K.; Devi, R.; Shepherd, V.; VillasBoas, P.J.F.; Jacinto, A.F.; Watanabe, H.A.W.; Oliveira, D.; Gordon, A.L. Research on Long-Term Care Homes for Older People in Brazil: Protocol for a Scoping Review. East Midl. Res. Ageing Netw. 2019, 32, 1–16.

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473.

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Soares, C.; Khalil, H.; Parker, D. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015 Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews; The Joanna Briggs Institute, Ed.; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2015.

- Trapé, T.L.; Campos, R.O. The Mental Health Care Model in Brazil: Analyses of the Funding, Governance Processes, and Mechanisms of Assessment. Rev. Saude Publica 2017, 51, 19.

- Pluye, P.; Robert, E.; Cargo, M.; Bartlett, G. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018. Regist. Copyr. 2018, 1148552, 10.

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Improving the Content Validity of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool: A Modified e-Delphi Study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 111, 49–59.

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 for Information Professionals and Researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291.

- Erlingsson, C.; Brysiewicz, P. A Hands-on Guide to Doing Content Analysis. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 7, 93–99.

- Fu, L.; Sun, Z.; He, L.; Liu, F.; Jing, X. Global Long-Term Care Research: A Scientometric Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2077.

- Bressan, V.; Cadorin, L.; Bianchi, M.; Barisone, M.; Rossi, S.; Bagnasco, A.; Carnevale, F.; Sasso, L. Research in Italian nursing practice: An extensive review of literature. Prof. Inferm. 2019, 72, 77–88.

- Medeiros, M.; Souza, P.H. The State and Income Inequality in Brazil; Discussion Paper; IPEA-Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2015. Available online: (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Goodman, C.; Davies, S. ENRICH: A New Innovation to Facilitate Dementia Research in Care Homes. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2012, 17, 277.

- Giacomin, K.C. Frente Nacional de Fortalecimento ás Instituições de Longa Permanência Para Idosos. Available online: (accessed on 25 October 2020).