Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is a debilitating condition that severely reduces the quality of life of a considerable proportion of cancer patients. There is no cure for CIPN to date. Here, we explore the potential of flavonoids as pharmacological agents in combating CIPN. Flavonoids alleviate CIPN by reducing oxidative stress, inflammation, and neuronal damage, among other mechanisms.

- flavonoids

- CIPN

- chemotherapy

- peripheral neuropathy

1. The Burden of CIPN and the Hope of Flavonoids

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is a common side effect of cancer treatment with antineoplastic agents. The neurotoxic effects of anticancer drugs lead to neuropathy in about 70% (up to 90% for oxaliplatin) of cancer patients [1]. Anticancer drugs that commonly induce peripheral neuropathy include plant alkaloids (e.g., vincristine, vinorelbine, and vinblastine), taxanes (e.g., docetaxel, paclitaxel, and cabazitaxel), platinum drugs (e.g., cisplatin and carboplatin), immunomodulatory drugs (e.g. thalidomide and pomalidomide), and proteasome inhibitors (e.g., bortezomib) [2]. These drugs damage sensory, motor, and autonomic nerves through various mechanisms, resulting in neuronal degradation [1]. Existing evidence shows that these mechanisms include proinflammatory cytokine release, oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, ion channel activation, ectopic discharge, microglial enhancement, and astrocyte activation. Besides these, other neuroinflammatory mechanisms are involved in the pathogenicity of CIPN [3,4,5,6,7]. Furthermore, there is evidence of a unique pattern of central pain processing in patients with CIPN; for example, the precuneus, a region implicated in conscious pain perception, is significantly more active in people with CIPN than in normal individuals during painful stimulation. Patients with CIPN also exhibit reduced activation of the right superior frontal gyrus, an area associated with subjectively unpleasant experiences such as pain [8].

CIPN can be acute, starting days or hours after chemotherapy, or chronic, starting several months after chemotherapy [7,9]. CIPN symptoms tend to worsen over time; this phenomenon is known as the “coasting effect” [10]. Symptoms include tingling, burning, freezing, electroshock-like sensations, numbness, weakness, and pain [2,10]. These symptoms have symmetrical effects and often follow a stocking and glove distribution, affecting the extremities [1]. CIPN is a debilitating condition that interferes with daily activities, causing emotional distress and reducing the quality of life [11,12]. Since its symptoms are dose-dependent, CIPN is also the leading cause of premature chemotherapy cessation, leading to reduced life span [1,10]. Moreover, peripheral neuropathy itself is associated with all-cause mortality in adults and can therefore be used as a marker for death risk [13].

Some treatments employed to manage CIPN include steroids, antidepressants such as duloxetine, numbing medications such as lidocaine and capsaicin, and antiseizure medications such as gabapentin and pregabalin [14,15]. While opioids are prescribed for those with extraordinarily severe or chronic CIPN, this practice is discouraged by the Centers for Disease Control due to the opioid epidemic [15]. Current treatments are based on other neuropathic pain models (diabetic, herpetic, and others) and have limited efficacy in CIPN.

Furthermore, there is no evidence for the pharmacological efficacy of antiseizure and antidepressant medications in treating CIPN [15]. Duloxetine is the only nonopioid pharmacological medication with consistent efficacy [15]. Unfortunately, recent in vivo and in vitro studies on CIPN states have yielded no major pharmacological advancements. Moreover, the majority of patients with CIPN receive no medical treatment for their symptoms [16]. These factors underscore the need for standardized, reliable treatments to improve cancer patients’ quality of life. Prior studies of CIPN mechanisms need to be thoroughly re-examined in light of contemporary studies investigating treatments. One class of compounds with the potential to relieve CIPN is flavonoids.

Flavonoids are secondary plant metabolites ubiquitous in fruits, vegetables, flowers, and barks [17]. They are phenolic compounds with variously substituted three-ring structures [18]. Flavonoids exert anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anxiolytic, neuroprotective, and anti-nociceptive properties [17], which grant alleviative effects in neuropathic pain models such as CIPN, diabetic neuropathy, and sciatic nerve chronic constriction injury [18,19]. Flavonoids’ anticancer properties depend on the previously mentioned activities and their apoptotic, anti-angiogenic effects; they also target the Warburg effect [20,21,22]. The neuroprotective effects of flavonoids may stem from their interference with the serotonin, dopamine, GABA, and glycine neurotransmitter (NT) pathways [18].

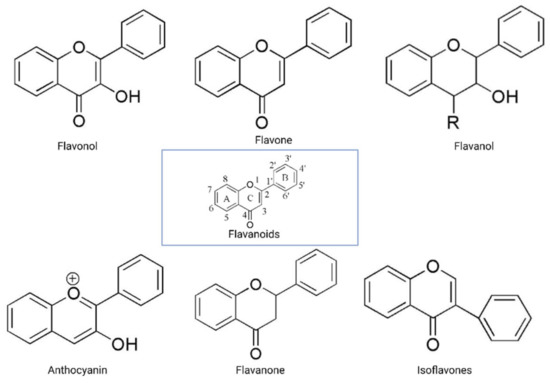

The flavonoid backbone consists of 15 carbon atoms arranged in the form of C6-C3-C6. Thus, it includes two benzene rings (A and B) connected by three carbon atoms, which may form a third (C) ring [17,23]. Structurally effective flavonoids consist of a catechol substructure on the A or B ring, a C3-OH group on the C ring, and an oxo group on C4. Above mentioned flavonoids’ beneficial effects are enhanced by a double bond between C2 and C3 due to planar molecule formation and increased double bond conjugation Figure 1 [23]. According to the carbon of the C ring, which is connected to the B ring and the oxidation and degrees of unsaturation of the C ring, flavonoids are classified into the following sub-groups: anthocyanins, flavanones, flavones, flavonols, flavanols, and isoflavones [17,23].

Structurally, flavones have two benzene rings linked by a heterocyclic pyrone ring (2-phenyl-chromones) [25]; essential members of this class include luteolin, apigenin, isoorientin, and icariin. Flavanones are dihydroflavones; therefore, the C ring and the bond between positions 2 and 3 are saturated [26]. Examples of flavanones are hesperetin, naringenin, silibinin, and eriodictyol. Flavanols–which include catechins and epicatechin–are the 3-hydroxy derivatives of flavanones [26]. Isoflavones have estrogenic properties and structures that include 3-phenyl-benzopyrone [27]; the main isoflavones are genistein, daidzein, biochanin A, and glycitein. Anthocyanins’ basic structural unit is the flavylium cation (2-phenylbenzopyrilium); this confers a positive charge on the oxygen skeleton. Most anthocyanins are acylated by organic acids through ester bonds. Important group members include cyanidin, delphinidin, malvidin, and peonidin. Finally, flavonols, such as quercetin, morin, and kaempferol, have a 2-phenyl-3-hydroxy- chromone backbone; rutin is a flavonol glycoside composed of quercetin and disaccharide rutinose [28,29]. The chemical structures of flavonoid classes can be seen in Figure 1.

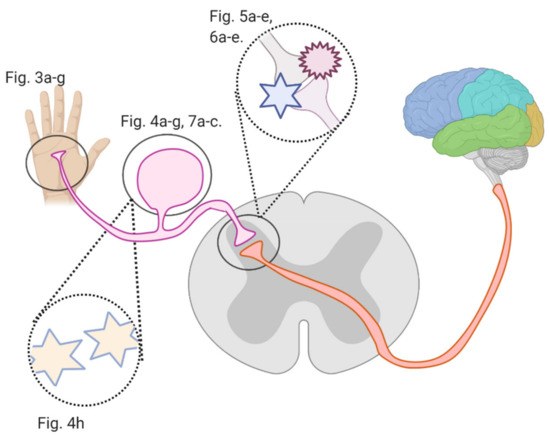

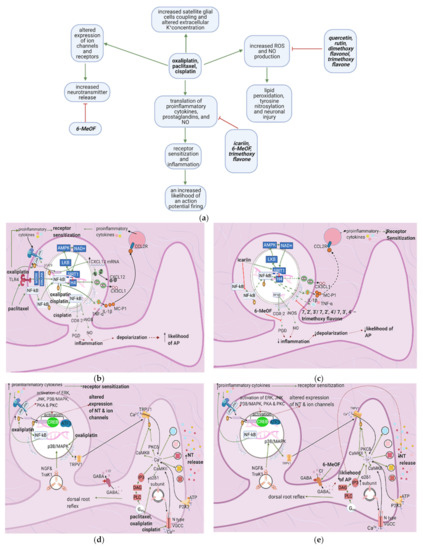

Several studies investigated flavonoids’ role in counteracting CIPN and reversing related oxidative stress and neuronal damage. The growing burden of CIPN and the emerging potential of flavonoids necessitate an analysis of the mechanisms by which flavonoids counter CIPN. Here, we review these mechanisms (see Figure 2) in the periphery, dorsal root ganglion, and spinal cord dorsal horn synapse, as well as in astrocytes and microglial cells.

2. Materials and Methods

PubMed and Google Scholar were searched using the following keywords: “flavonoids”, “CIPN”, “neuropathic pain”, and “peripheral neuropathy”. One hundred thirty-four results were obtained for the combination “flavonoids” AND “CIPN”, 6620 for “flavonoids” AND “neuropathic pain”, and 4909 for “flavonoids” AND “peripheral neuropathy”. We included studies that investigated the effects of flavonoids on models of CIPN, sciatic nerve chronic constriction injury (CCI), partial sciatic nerve ligation (PNL), spared nerve injury (SNI), and spinal nerve ligation (SNL); the latter four share mechanisms with CIPN. We included studies with nerve injury models only if their findings were likely to be generalizable to CIPN (i.e., they investigated a mechanism in common with CIPN). Studies on diabetic, herpetic, or other clinically manifesting peripheral neuropathies apart from CIPN were excluded. We only included studies discussing peripheral nervous system mechanisms. These inclusion criteria encompassed 8 studies on CIPN and flavonoids; we selected seven. Similarly, we found 18 studies investigating flavonoids with CCI, SNL, PNL, and SNI, and included four.

3. Flavonoids Counter the Effects of Anticancer Drugs at the Peripheral Nociceptor

3.1. General Effects of Anticancer Drugs and Flavonoids

3.2. Effects of Anticancer Drugs

3.2.1. Ion Channel Activation

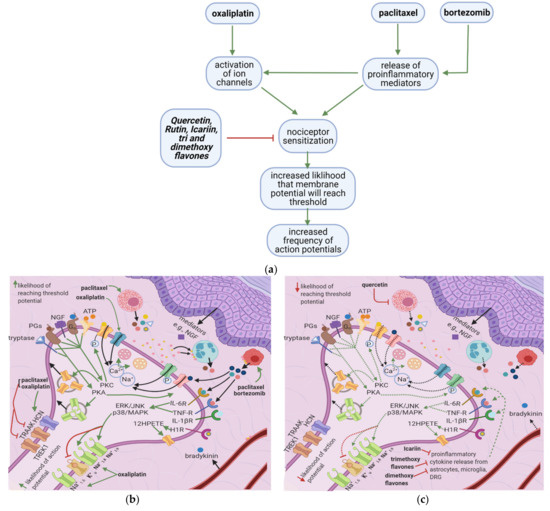

Oxaliplatin upregulates the expression of transient receptor potential melastatin 8 (TRPM8) [10,16], causing cold allodynia. It also activates TTX-R Na+1.8 (involved in action potential initiation), TTX-R Na+1.6, and HCN (hyperpolarization-activated channels involved in action potential propagation) while inhibiting TREK1 and TRAAK (potassium channels which restore the membrane potential to the resting state) [11]. Furthermore, nerve growth factor (NGF) and ATP activate protein kinase C (PKC) through their actions on TrkA1 and P2X3, respectively; PKC, in turn, increases the membrane fusion of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) vesicles [17,18]. These increases in ion channel activity and density destabilize the nociceptor membrane and cause the neuron to exhibit oscillatory behavior.

3.2.2. Release of Proinflammatory Mediators

Paclitaxel induces mast cell degranulation [19], causing the release of the inflammatory mediators TNF-∝, IL-1β, IL-6, histamine, prostaglandins, and tryptase [20]. Paclitaxel and bortezomib activate macrophages [1,2], which release ROS, TNF-∝, and IL-1β [21]. These mediators act on their respective receptors, inducing a series of events that raise the membrane potential [22] (Figure 3b).

ROS directly acts on and sensitizes transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) [23] (Table 1), while TNF-∝ and IL-1β act on TNF-R and IL-1R, respectively, leading to extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation and p38/MAPK signaling [17] (Figure 3d). IL-1β also acts directly on TRPV1, increasing ionic inflow through this channel [17]. IL-6 stimulates IL-6R, causing the activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK), ERK, and p38/MAPK [17]. The IL-6/IL6-R complex subsequently activates PKCδ, which sensitizes TRPV1 [24]. Activation of p38/MAPK leads to phosphorylation of Na+1.8 and Na+1.9 and inhibition of K+v activity [8,17,25]. The recruitment of ERK, JNK, and p38/MAPK pathways result in increased phosphorylation and activation of transcription factors in the DRG; thus, more ion channels are synthesized (long-term changes) [17] (Figure 3f). Changes in ion channel density on the nociceptor membrane raise the resting membrane potential toward the threshold, increasing the likelihood that an action potential will result from stimuli too weak to cause one under normal conditions.

Table 1. Mechanisms of CIPN at the peripheral nociceptor induced by anticancer therapy.

|

Mechanism of CIPNP |

Neuropathic Pain Model |

Mode of Administration/Concentration |

Animal Model |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Increased macrophage infiltration |

Paclitaxel and bortezomib induced |

(in vitro) IV bortezomib 0.2 mg/kg, 3 times a week for 8 weeks (in vitro) 2 doses of 18 mg/kg paclitaxel given 3 days apart |

Female Wistar rats Adult Male Sprague Dawley Rats |

|

|

Sensitization of TRPA1 via increased production of ROS, RNS, and RCS. |

Oxaliplatin induced Cisplatin induced Paclitaxel induced |

Intraperitoneal/3 mg/kg Intravenous/ 2 mg/kg Intraperitoneal/3 times per week for 5 weeks (2 mg/kg) Intraperitoneal/6 mg/kg |

Male Dunkin-Hartley guinea pigs, male Sprague-Dawley rats, male C57BL/6 mice, wild-type (Trpa1+/+) or TRPA1-deficient mice (Trpa1–/–) Male C57BL/6 mice, wild-type (Trpa1 +/+), or TRPA1-deficient mice (Trpa1 –/–) |

|

|

Increased expression of FKN, which binds to CX3CR1, increasing ROS production and enhancing trafficking of macrophages to the sciatic nerve. ROS activated TRPA1, evoking pain. |

Vincristine induced |

Intraperitoneal/0.5 mg/kg for two 5 day cycles |

Adult male and female C57BL/6 J mice |

[34] |

|

Increased production of tryptase, which cleaves PAR2, causing increases in PKC∈ and PKA. PKA sensitizes TRPV1, TRPV4 and TRPA1, whereas PKC ∈ sensitizes TRPV1 and TRPV4. |

Paclitaxel induced |

Intraperitoneal/ Four doses of 1 mg/kg every two days |

Male ICR mice |

[35] |

|

IL-1β increases TTXR Na+ currents via the p38/MAPK pathway. |

Isolated DRG cells |

IL-1β (10 ng/mL) applied using multibarrel fast drug delivery system |

Male Sprague-Dawley Rats |

[36] |

|

TNF- α increases TTXR Na+ currents via the p38/MAPK pathway |

Isolated DRG cells |

(in vitro) recombinant murine TNF-α (50 µg/mL) solution (in vivo) 1ng of TNFα- in 10 µL injected into rat hind paw plantar surface |

ICR adult male mice |

[37] |

|

Application of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 on peripheral nociceptors dose-dependently led to cGRP release |

Incubated skin flaps |

(in vitro) murine TNF-α (0.05–500 ng), murine IL-1β (0.02–200 ng), human IL-8 (0.1 ng to 1 μg), mIL-6 (0.02–200 ng) |

Male Wistar rats |

[38] |

|

Increased expression of TRPA1 and TRPV1 in small sized DRG neurons and TRPM8 in medium sized DRG neurons. |

Oxaliplatin induced |

(in vitro) Intraperitoneal One dose of 6 mg/kg |

Male Wistar rats |

[39] |

|

Increased expression of HCN and decreased expression of TREK1 and TRAAK channels. |

Oxaliplatin induced |

(in vitro) Intraperitoneal 3 injections (1,3,6 mg/kg) |

Male C57BL6J mice |

[40] |

3.3. Flavonoids Counteract the Effects of Anticancer Drugs

3.3.1. Icariin, Trimethoxy- and Dimethoxyflavones

In paclitaxel-induced models of CIPN, the flavonoid icariin inhibited the release of IL-1β, TNF-∝, and IL-6 from the DRG, astrocytes, and microglia [13], while trimethoxy and dimethoxy flavones inhibited the release of IL-1β, TNF-∝, and free radicals [14,15] (Table 2). Decreased action of proinflammatory cytokines on the nociceptor would render p38/MAPK, ERK, and JNK less active, decreasing the activation and synthesis of TTX-Resistant Na+v channels (Figure 3g). Thus, the membrane potential would be less likely to reach the threshold potential (Figure 3c). These factors may account for the reduction of tactile allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia by trimethoxy and dimethoxy flavones and of mechanical allodynia by icariin [13,14,15].

Table 2. Role of flavonoids in countering CIPN mechanisms at the peripheral nociceptor.

|

Flavonoid |

Neuropathic Pain Model |

Animal Model |

Flavonoid Concentration |

Mechanism-based Intervention |

Effect on Neuropathy |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Quercetin |

Paclitaxel induced |

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats and Institute of Cancer Research mice |

3, 10 and 30 μmol/L (in vitro) Intragastric administration of 20 mg/kg or 60 mg/kg once per day for 40 days for rats and 12 days for mice (in vivo) |

Inhibited degranulation of mast cells, PKC epsilon translocation from the cytoplasm to the cell membrane |

Dose-dependent increase of thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia thresholds |

[41] |

|

Icariin |

Paclitaxel induced |

3 to 4 month old male Sprague Dawley Rats |

(in vitro and in vivo) 25, 50,100 mg/kg |

Reduction of IL-1 β, TNF-α and IL-6 release from the DRG, astrocytes, and microglia |

Decreased mechanical allodynia and spinal neuroinflammation |

[42] |

|

Trimethoxy flavones |

Paclitaxel induced |

Adult swiss Albino mice of either sex |

(in vitro and in vivo) 25, 50, 100 or 200 mg/kg |

Concentration-dependent decrease of IL-1β, TNF-α, and free radicals |

Dose-dependent decrease of tactile allodynia, thermal hyperalgesia, and cold allodynia |

[43] |

|

Dimethoxy flavones |

Paclitaxel induced |

Male Swiss Albino Mice |

(in vitro and in vivo) 25, 50, 100 or 200 mg/kg |

Concentration-dependent decrease of IL-1β, TNF-α, and free radicals |

Dose-dependent decrease of tactile allodynia, thermal hyperalgesia and cold allodynia |

[44] |

3.3.2. Quercetin

4. Flavonoids Counter the Effects of Anticancer Drugs at the Dorsal Root Ganglion

4.1. General Effects of Anticancer Drugs and Flavonoids

4.2. Effects of Anticancer Drugs

4.2.1. Upregulation of the NF-κB Pathway

4.2.2. Increase in Intracellular Ca2+

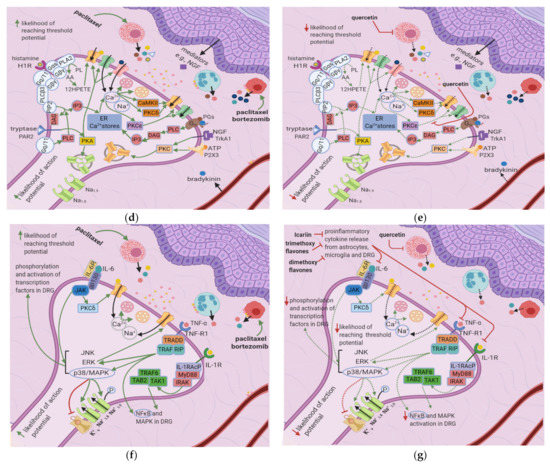

Cisplatin increases N-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (VGCC) density in small DRG neurons [49] by activating CaMKII [50]. Paclitaxel and oxaliplatin upregulate the α2δ1 subunit [51,52] (Table 3), which increases VGCC currents, prolongs the neuronal response to mechanical and thermal stimuli, and increases pain [50]. Elevated VGCC mRNA and protein expression [50] increase VGCC density at the presynaptic membrane; therefore, more Ca2+ enters the presynaptic terminal. Prostaglandins and bradykinin act on G, upregulating IP3 and increasing intracellular Ca2+ release [53]. ATP acts on P2X purinoceptor 3 (P2X3), leading to an increase in intracellular Ca2+ [53]. Ca2+ activates CaMKII and PKC epsilon, which phosphorylate and activate TRPV1 [53]. Ca2+ also increases the fusion of vesicles containing substance P, cGRP, and glutamate with the presynaptic membrane [53] (Figure 4e). The result is an increased probability of postsynaptic action potential generation and a consequent increase in neuropathic pain severity.

Table 3. Previous studies investigating the mechanisms by which anticancer drugs exert their effects on the DRG.

|

Mechanism of CIPNP |

Neuropathic Pain Model |

Mode of Administration/ Concentration |

Animal |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Increased VGCC current density in DRG neurons via CaMKII; Increased VGCC protein levels |

Cisplatin induced |

5 mg/kg (in vivo), 0.5 μM and 5 μM (in vitro) |

Male and female Wistar rats for in vitro procedures. Male Sprague-Dawley rats for in vivo procedures |

[49] |

|

Upregulation of VGCC α2δ1 subunit in DRG |

Paclitaxel induced |

IP/4 mg/kg single injection; 4 mg/kg administered 4 times on alternate days Intravenous/ 4 mg/kg single injection |

Male ddY mice |

[57] |

|

Increased phosphorylation of STAT3; increased levels of CXCL12 mRNA and protein |

Oxaliplatin induced |

IP/5 injections of 4 mg/kg each, administered on consecutive days |

Male Sprague–Dawley rats |

[58] |

|

Upregulation of p65 mediated CX3CL1 expression in DRG |

Oxaliplatin induced |

Intraperitoneal/ 5 injections of 4 mg/kg each, administered on consecutive days |

Male Sprague-Dawley rats |

[59] |

|

Downregulation of SIRT1 expression and an increase in histone acetylation; induction of NF-κB(p65) activation and nuclear translocation; upregulation of proinflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1b, IL-6 ); Activation of astrocytes |

Paclitaxel induced |

IP/8 mg/kg per day for 3 consecutive days |

Male Sprague Dawley rats |

|

|

increased lipid peroxidation and protein nitrosylation; increased inducible nitric oxide synthase. |

Oxaliplatin induced |

IV/1 mg/kg dose twice a week (total of nine injections). |

Male Swiss mice |

[56] |

|

Increased TNF-α, IL-1β, DPPH, and NO. |

Paclitaxel induced |

IP/A single dose (10 mg/kg) |

Male Swiss albino mice |

[44] |

|

Stimulates COX-2 expression |

Cisplatin induced |

IP/3 mg/kg once a week for four consecutive weeks. |

Male Sprague-Dawley rats |

[48] |

|

TLR4 signaling in the spinal cord dorsal horn and DRG induces and maintains CIPN |

Paclitaxel induced |

IP/4 injections of 2 mg/kg administered every other day |

Male Sprague-Dawley rats |

[60] |

|

Upregulation of CX3CL1 via NF-κB–dependent H4 acetylation |

Paclitaxel induced |

IP/3 injections of 8 mg/kg, on 3 alternate days |

Male Sprague-Dawley rats |

[46] |

|

Increased expression of CCL2/CCR2 leading to innate immune response |

Oxaliplatin induced |

IP/1 injection of 3mg/kg |

Male Sprague-Dawley rats |

[47] |

|

Increased the expression of TRPV1 |

Oxaliplatin induced |

IP/I injection of 6 mg/kg |

Male Wistar rats |

[39] |

|

Increased VGCC expression mediated by CaMKII |

Oxaliplatin induced. |

In vitro and in vivo w/ variant conc |

Wistar rats |

[61] |

|

Increased gap-junctional coupling among SGCs; increased GFAP production |

Taxol and Oxaliplatin induced |

Oxaliplatin–IP/ 2 injections of 4 mg/kg–3 days apart. Taxol- IP/ 2 injections of 18 mg/kg–3 days apart |

Balb/c mice |

[62] |

|

increased ROS, GFAP, and Cx-43 decreased Kir4.1 channels |

Oxaliplatin induced |

in vitro/ 1 and 10 μM for 2,4 and 24 h. |

[63] |

|

|

Peripheral neuropathic pain associated with increase in ∝2δ1 subunit in spinal cord |

Paclitaxel induced Oxaliplatin induced |

In vitro/Intraperitoneal 2 mg/kg paclitaxel on 4 alternate days In vitro/ 6 mg/kg oxaliplatin intraperitoneal |

Adult male Sprague Dawley Rats Male Wistar rats |

|

|

Increased N-type VGCC density in small DRG neurons |

Cisplatin induced |

In vitro/0.5 μM and 5 μM incubated for 24 or 48 h. |

Male and female Wistar rats |

[49] |

4.2.3. Increased GABA Release

4.2.4. Enhanced Activation of Satellite Glial Cells

4.2.5. Increased Oxidative Stress

4.3. Flavonoids Counteract the Effects of Anticancer Drugs

4.3.1. Icariin

4.3.2. Quercetin, Rutin, and Trimethoxy and Dimethoxy Flavones

Flavonoids alleviate anticancer drug effects by decreasing oxidative stress in the DRG. Quercetin and rutin counteract oxaliplatin’s effects by directly increasing GSH levels and scavenging ROS [56]. Quercetin also decreases the levels of catalase and superoxide dismutase (SOD) and consequently decreases lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation. 7,2′,3′/7,2′,4′/–,7,3′,4′/7,5,4′–trimethoxyflavones and 3′,4′/6,3′/7,2′/7,3′- dimethoxyflavanol also counteract paclitaxel-induced neurotoxicity by scavenging DPPH and nitric oxide [43] (Figure 4g) (Table 4). These flavonoids also inhibit the production of TNF–α and IL-1β [34].

Table 4. Previous studies investigating the effects of flavonoids on CIPN models at the DRG.

|

Flavonoid |

Neuropathic Pain Model |

Animal |

Mode of Administration/ Concentration of Flavonoid |

Mechanism-Based Intervention |

Effect on Neuropathy |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Icariin |

Paclitaxel induced |

Male Sprague Dawley rats |

IG/25, 50, 100 mg/kg. |

Activated SIRT1 via histone acetylation; Prevented NF-κB(p65) phosphorylation and nuclear translocation; prevented the production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β; Suppressed astrocyte activation. |

Alleviated mechanical allodynia. (100 mg/kg in the long term) and spinal neuroinflammation. |

[42] |

|

Rutin and quercetin |

Oxaliplatin |

Male Swiss mice |

IP/ rutin or quercetin (25, 50, and 100 mg/kg) 30 min before every oxaliplatin injection (1 mg/kg). |

Decreased Fos expression; Decreased nitrotyrosine and iNos expression, and lipid peroxidation. |

Inhibited the decrease in mechanical (a.d) and cold nociceptive threshold. Prevented the shrinkage of dorsal horn neurons |

[56] |

|

7, 2′, 3′/7,2′, 4′/–,7,3′,4′/7, 5,4′–trimethoxy flavone |

Paclitaxel |

Male and female adult Swiss albino mice |

SC injection/ 25, 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg. |

Inhibition of TNF–α, IL–1β (d.d). Scavenging DPPH; Preventing NO generation (d.d) |

Alleviated tactile allodynia, cold allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in mice |

[43] |

|

3′,4′/6,3′/7,2′/7,3′-dimethoxy flavonol |

Palcitaxel |

Male Swiss albino mice |

SC/25, 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg |

Decreased TNF-α, IL-1β (d.d); Scavenged DPPH and NO (d.d) |

Improved tactile allodynia, cold allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia(d.d) |

[44] |

|

6-Methoxyflavone |

Cisplatin |

Male Sprague-Dawley rats |

Intraperitoneal/25, 50 and 75 mg/kg Also conducted in silico and in vitro studies |

Inhibits COX-2; Stimulates GABAA channels |

Improved static and dynamic allodynia |

[48] |

5. Flavonoids Counter the Effects of Anticancer Drugs at the Spinal Cord Dorsal Horn

5.1. General Effects of Anticancer Drugs and Flavonoids

5.2. Effects of Anticancer Drugs

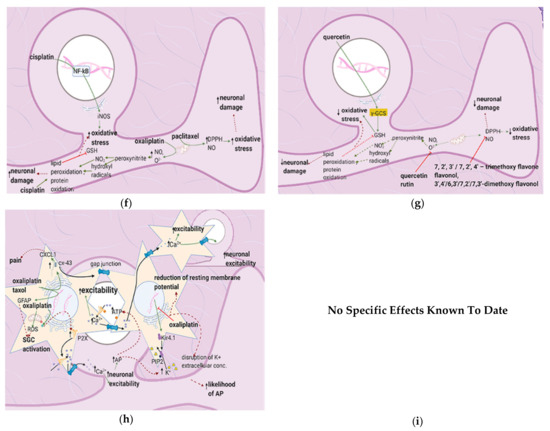

Cisplatin and carboplatin are ligands for TLR4 [7,64], and cisplatin upregulates the TREM-2 ligand [68] (Table 5). Subsequent activation of the TLR4 and TREM-2 pathways eventually results in NF-κB activation, culminating in proinflammatory cytokine release by astrocytes and microglial cells [69]. Chemokines released by DRG neurons, such as CX3CL1, also cause NF-κB activation and proinflammatory cytokine release [7,70] (Figure 5b). Proinflammatory cytokines cause peripheral sensitization via the processes mentioned in Section 2; IL-1β acts on IL-1R on astrocytes, stimulating NF-κB activation and hence the release of more proinflammatory cytokines [71]. These cytokines also stimulate the fusion of presynaptic glutamate vesicles with the DRG neuron membrane [67].

Table 5. Studies investigating the mechanisms by which anticancer drugs exert their effects.

|

Mechanism of CIPN |

Neuropathic Pain Model |

Mode of Administration/Concentration |

Animal |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Strong TREM2/DAP12 signaling continuously activated microglial cells, which resulted in neuropathic pain. |

Cisplatin induced |

Intraperitoneal/Accumulated dose of 23 mg/kg delivered in 2 rounds daily for 5 days with a 5 day break between rounds. (in vitro and in vivo) |

Adult male mice, 9–10 weeks old |

[68] |

|

Oxaliplatin upregulates spinal CX3CLI, causing central sensitization and acute CIPN |

Oxaliplatin induced |

Intraperitoneal/single dose of 4 mg/kg (in vitro and in vivo) |

Male Sprague Dawley rats |

[70] |

|

Increased S1P, S1PR1, and dihydro-S1P due to dysregulated sphingolipid metabolism |

Bortezomib induced |

(in vitro and in vivo) |

Male Sprague Dawley rats, S1pr1 knockout and knockdown mice |

[67] |

|

Downregulation of GLAST and GLT-1 on astrocyte membranes |

Paclitaxel induced |

Intraperitoneal/4 injections of 2 mg/kg every other day (in vitro) |

Adult Male Sprague Dawley Rats, 8–10 weeks old |

[66] |

|

Upregulation of CX43 gap junctional proteins in astrocytes in the spinal cord dorsal horn |

Oxaliplatin induced |

Intraperitoneal/4 injections of 2mg/kg each given every other day. (in vitro and in vivo) |

Male Sprague Dawley rats |

[65] |

5.3. Flavonoids Counter the Effects of Anticancer Drugs

Quercetin and Icariin

The flavonoid quercetin inhibits mast cell degranulation and PKC epsilon movement to the membrane, thus decreasing the activation of TRPV1 (Figure 5e) [41]. This reduces Ca2+ entry and thus the fusion of vesicles with the membrane, decreasing the likelihood of a postsynaptic action potential. Icariin inhibits NF-κB in the spinal cord dorsal horn (Figure 5e) (Table 6); thus, fewer proinflammatory cytokines are released, reducing the fusion of vesicles with the membrane. Overall, the frequency of action potentials in the postsynaptic neuron decreases, decreasing neuropathy intensity [42] (Figure 5c).

Table 6. Studies investigating the effects of flavonoids on CIPN models.

|

Flavonoid |

Neuropathic Pain Model |

Animal |

Mode of Administration/ Concentration of Flavonoid |

Mechanism-based Intervention |

Effect on Neuropathy |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Quercetin |

Paclitaxel induced |

adult male Sprague-Dawley rats and mice |

3, 10 and 30 μmol/L (in vitro) Intragsteral administration of 20 mg/kg or 60 mg/kg once per day for 40 days for rats and 12 days for mice (in vivo) |

Inhibited degranulation of mast cells and membrane translocation of PKC epsilon |

Dose dependent increase of thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia thresholds |

[41] |

|

Icariin |

Paclitaxel induced |

Male Sprague Dawley rats |

IG/25, 50, 100 mg/kg. |

Suppressed GFAP and astrocyte production of TNF-α, IL-1b, and IL-6. |

Alleviated mechanical allodynia (100 mg/kg in the long term) and spinal neuroinflammation. |

[42] |

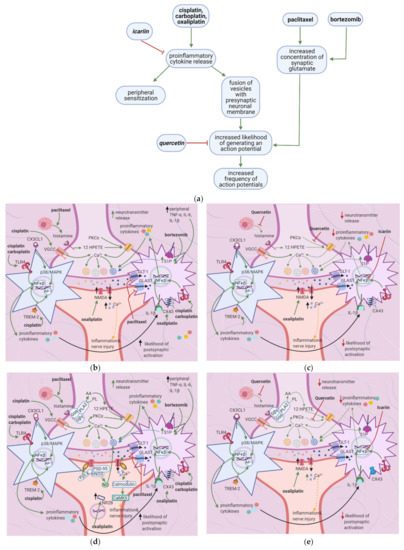

6. Flavonoids Counter the Effects of Anticancer Drugs on Astrocytes and Microglial Cells at the Spinal Cord Dorsal Horn

6.1. General Effects of Anticancer Drugs and Flavonoids

6.2. Effects of Anticancer Drugs

6.2.1. Upregulation of the S1P Pathway

Bioactive sphingolipid metabolites are potent signaling molecules involved in bortezomib-induced CIPN. Bortezomib affects the S1P signaling pathway by increasing ceramide and its biosynthetic precursors such as S1P (Figure 6b). As astrocytes express S1PR1 (at higher levels than glial cells), they mediate bortezomib-induced CIPN; S1P triggers them to become reactive (Table 7). This form of astrocyte activation is associated with increases in GFAP, TNF, and IL-1β. S1PR1-induced inflammation establishes a feed-forward mechanism that dysregulates sphingolipid production, as TNF and IL-1β cause the activation of enzymes in the ceramide and S1P pathways. S1PR1 also increases glutamate release, which sustains neuropathic pain [67].

Table 7. Previous studies investigating the mechanisms by which anticancer drugs exert their effects.

|

Mechanism of CIPNP |

Neuropathic Pain Model |

Mode of Administration/ Concentration |

Animal |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Increased sphingosine metabolism and consequently increased ceramide, DH-S1P, and SIP. Increased TNF-α and IL-1β in blood plasma |

Bortezomib induced |

Intraperitoneal/total 1 mg/kg over 5 consecutive days (0.2 mg/kg per day) and Intraperitoneal/0.4 mg/kg every other day 3 times a week for 4 weeks |

Male Sprague Dawley rats and GFAP-Cre breeder mice |

[67] |

|

Upregulated TREM 2 ligand and thus increased TREM2/DAP12 complex signaling, leading to the activation of microglial cells |

Cisplatin induced |

Intraperitoneal/ 23mg/kg spread over 2 rounds of 5 consecutive days with a 5day break |

Adult male mice |

[68] |

|

Increase in the astrocyte-specific gap junctional protein CX43 in the spinal cord, leading to enhanced astrocyte activation. |

Oxaliplatin induced |

Intraperitoneal/4 injections of 2 mg/kg each, every other day |

male Sprague-Dawley rats |

[65] |

|

Downregulation of GLAST and GLT-1 in the spinal cord dorsal horn led to excessive activation of postsynaptic AMPA and NMDA receptors |

Paclitaxel induced |

Intraperitoneal/1 mg/kg per day for 4 consecutive days Intraperitoneal/1.0 mg/kg on 4 alternate days, total 4 mg/kgIntraperitoneal/2 mg/kg every other day for total 4 injections |

male Sprague–Dawley ratsadult male Sprague–Dawley rats Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats |

|

|

TLR4, through MYD 88 and TRIF, plays an integral role in nociceptive signaling. |

Cisplatin induced |

Intraperitoneal/ Six injections of 2.3 mg/kg given every other day |

Wild type C57BL/6 mice; Tlr3–/–, Tlr4–/–, and Myd88–/– mice |

[64] |

|

TLR4 signaling in the spinal cord dorsal horn and DRG induces and maintains CIPN |

Paclitaxel induced |

Intraperitoneal/4 injections of 2 mg/kg administered every other day |

Male Sprague-Dawley rats |

[60] |

6.2.2. Upregulation of the TLR4 Pathway

6.2.3. Increased Expression of Cx-43

6.2.4. Downregulation of Glutamate Uptake Receptors and Increased GFAP

6.2.5. Enhanced TREM2/DAP12 Signalling

6.2.6. Increased CX3CL1 Expression

6.3. The Flavonoids Icariin and Astragli Radix Counter the Effects of Anticancer Drugs

Icariin counteracts paclitaxel-induced GFAP expression and thus represses astrocyte activation. Icariin also inhibits the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in the spinal cord [42] (Table 8) (Figure 6c). In addition to isolated flavonoids, Astragali radix is an adaptogenic herbal product that improves chemotherapy patients’ quality of life. Astragai radix is rich in various phytochemicals, including isoflavonoids, while isoflavones are more concentrated in hydroalcoholic extracts of Astragali radix when compared with aqueous. Besides, 50% hydroalcoholic extracts of Astragali radix reduced ATF-3 nuclear immunoreactivity in L4-L5 DRG, oxaliplatin-induced molecular and morphometric alterations in peripheral nerve and dorsal root ganglia, and the activation of microglia and astrocytes in a Sprague-Dawley rat model of oxaliplatin-induced neurotoxicity [73].

Table 8. Previous studies investigating the effects of flavonoids on CIPN models.

|

Flavonoid |

Neuropathic Pain Model |

Animal |

Mode of Administration/Concentration of Flavonoid |

Mechanism-based Intervention |

Effect on Neuropathy |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Icariin |

Paclitaxel induced |

Male Sprague Dawley rats |

IG/25, 50, 100 mg/kg |

Suppressed GFAP and astrocyte production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. |

Alleviated mechanical allodynia (100 mg/kg in the long term) and spinal neuroinflammation. |

[42] |

|

Astragali radix |

Oxaliplatin-induced neurotoxicity |

Male Sprague Dawley rats |

50% hydroalcoholic extracts of Astragali radix |

Numerical reduction of astrocytes within the dorsal horns (demonstrated by GFAP immunohistochemistry) |

Reduction of Oxaliplatin-induced molecular and morphometric alterations in peripheral nerve and dorsal-root ganglia. Decrease in the activation of microglia and astrocytes |

[73] |

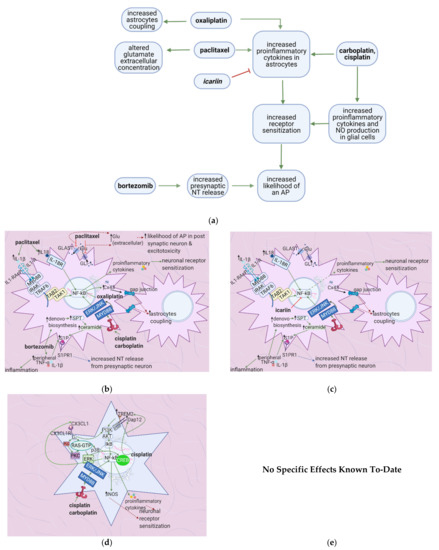

7. Flavonoids Counter Neuronal Injury Induced by Anticancer Drugs

7.1. General Effects of Anticancer Drugs and Flavonoids

7.2. Effects of Anticancer Drugs

7.2.1. Mitochondrial Damage

Paclitaxel increases the activity of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) channel [76] (Table 9). Consequently, more Ca2+, caspases, and calpains leave the mitochondria; caspases and calpains trigger neuronal apoptosis [77]. Furthermore, paclitaxel, vincristine, and bortezomib disrupt microtubules (Figure 7b) [82,83]. Paclitaxel causes microtubules to polymerize and inhibits their depolymerization [84]. Platinum compounds cause DNA adducts to form within mitochondria and the neuronal nuclei [85]. Nuclear DNA adducts activate PARP, decreasing mitochondrial NAD+ and ATP and causing further mitochondrial damage [86]. Under these low ATP conditions, intraepidermal nerve fibers are lost [87].

Table 9. Previous studies investigating the mechanisms by which anticancer drugs exert their effects.

|

Mechanism of CIPNP |

Neuropathic Pain Model |

Mode of Administration/Concentration |

Animal |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Downregulation of MnSOD through post translational nitration by peroxynitrite. |

Paclitaxel, oxaliplatin, bortezomib |

Intraperitoneal; Paclitaxel: 4 doses delivered on alternate days, cumulative dose of 8 mg/kg Oxaliplatin: 10 mg/kg delivered over 5 consecutive days Bortezomib: 1 mg/kg delivered over 5 consecutive days |

Male Sprague Dawley rats |

[91] |

|

Formation of DNA adducts |

Cisplatin |

2 microgram/ml for 48 h (in vitro) |

Harlan–Sprague–Dawley rats and wild type background mice (C57BL/6J) |

[85] |

|

Increased permeability of mPTP |

Paclitaxel |

Intraperitoneal/ 1 ml/kg on 4 alternate days (in vitro and in vivo) |

Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats |

[92] |

|

Increased LPS-induced iNOS expression |

Oxaliplatin |

i.v./nine injections of 1 mg/kg each given twice a week (in vitro and in vivo) |

male Swiss mice |

[56] |

7.2.2. Neuronal Damage

7.2.3. Enhanced iNOS Expression

7.3. Flavonoids Counter the Effects of Anticancer Drugs

The flavonoids morin and GSPE restore GSH levels, and morin restores ATP levels (Figure 7c) [78,79]. Increased ATP levels restore the activity of the Na+/K+ exchanger, decreasing ectopic activity and thus neuropathic pain, while elevated GSH levels reduce H2O2 and ROS production. These effects reduce the chance of apoptosis and also decrease ectopic activity. Thus, spontaneous pain, ongoing pain, and mechanical hypersensitivity will all decrease. Genistein restores mitochondrial GPX levels while isoorientin ameliorates axonal swelling and prevents demyelination [80,81]. Quercetin, rutin, and genistein reduce LPS-induced iNOS expression [56,81] and thereby reduce ONO2- production and DNA adduct formation. Besides, the natural flavonoid silibinin prevents oxidative damage and exerts antineuropathic effects in a rat model of painful oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy [90] (Table 10).

Table 10. Previous studies investigating the effects of flavonoids on CIPN models.

|

Flavonoid |

Neuropathic Pain Model |

Animal |

Mode of Administration/Concentration of Flavonoid |

Mechanism Based Intervention |

Effect on Neuropathy |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Genistein |

Chronic constriction sciatic nerve injury |

C57BL/6J male mice |

Subcutaneously/once a day for 11 days at doses of 1,3,7.5,15,30 mg/kg (in vitro and in vivo) |

Restoration of mitochondrial GPX levels, and reduction of LPS-induced iNOS production |

Reversal of mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in a time and dose-dependent manner |

[81] |

|

Morin |

Chronic constriction injury |

Male Sprague-Dawley rats |

Oral/30 mg/kg for 14 days (in vitro and in vivo) |

Reduced PARP overactivation and nitrite levels. Restored ATP and glutathione levels; repaired DNA damage |

Reversed mechanical, chemical, and thermal hyperalgesia |

[78] |

|

Isoorientin |

Chronic constriction injury |

Adult, male specific pathogen free mice from ICR |

Intragastric/7.5, 15 or 30 mg/kg per day |

Ameliorated axonal swelling; prevented demyelination |

Reduced hyperalgesia and allodynia |

[80] |

|

Quercetin and rutin |

Oxaliplatin induced |

male Swiss mice |

i.v./nine injections of rutin (25, 50, and 100 mg/kg) or quercetin (25, 50, and 100 mg/kg) given twice a week (in vitro and in vivo) |

Decreased LPS-induced iNOS expression |

Inhibition of thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia |

[56] |

|

GSPE |

Chronic constriction injury |

Wistar rats of either sex |

Oral/100 and 200 mg/kg for 14 days (in vitro and in vivo) |

Increased SOD and GSH |

Attenuation of thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia |

[79] |

|

Silibinin |

Oxaliplatin |

Rat model of painful oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy |

Silibinin (100 mg/kg), administered once a day, starting from the first day of oxaliplatin injection until the 20th |

Prevention of oxidative damage |

Antineuropathic effects |

[90] |

8. Flavonoids: Promise, Applications, and Side Effects

CIPN is a multifactorial disease with various pharmacological mechanisms. Effective treatments should influence the mechanisms that contribute most to the symptoms. Damage to DRG neuronal cell bodies or axons contributes most strongly to CIPN symptom development. Likewise, flavonoids with the most success in animal models affect these areas by reducing peripheral sensitization of DRG neurons, modulating synaptic transmission at the spinal dorsal horn, and reducing mitochondrial damage in DRG neurons, among other mechanisms. However, how these mechanisms interact with and influence each other to cause symptoms still requires extensive investigation.

Moreover, pain results from interactions between central and peripheral mechanisms [93,94]. More information about central-peripheral interaction and central nervous system mechanisms of pain transmission (neuromodulators, neuroplasticity, central sensitization, and NTs) is needed to understand the pathophysiology of CIPN [50] entirely. Also, there are many clinical phenotypes of CIPN, and each requires a specific standardized treatment approach. For example, oxaliplatin and paclitaxel induce neuropathy through different mechanisms [93]. Adding a different complexity level, combinations of different anticancer drugs are used in treatment regimens [4,95].

Moreover, a specific flavonoid will alleviate some, but not all, symptoms. For example, 6-methoxyflavone [18] alleviates static and dynamic allodynia, whereas dimethoxyflavonol inhibits tactile allodynia [44], and quercetin decreases the thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia thresholds [41]. Therefore, since CIPN involves many symptoms, and specific flavonoids counteract specific anticancer drugs, combination therapies warrant further investigation [3].

It is essential to consider the concentrations of flavonoids that are useful in the treatment of CIPN. Flavonoids are present in relatively low concentrations in fruits and vegetables; these sources also contain a mixture of secondary plant metabolites such as vitamin C, folate, potassium, and fiber [96]. These secondary metabolites have known health benefits that cannot be replaced by a single compound (e.g., flavonoids) given as a dietary supplement [96]. Suppliers of flavonoid supplements recommend daily doses many times higher than those found in a flavonoid-rich diet. For example, quercetin is offered as a supplement with daily doses of 1 g or more [96], while its daily dietary intake is estimated to be between 10–100 mg [96].

Other issues to be considered in evaluating flavonoids as dietary supplements include drug interactions, trace element chelation, and thyroid status [97]. In vitro experiments indicate that purified flavonoids and flavonoid-rich extracts chelate iron, posing a risk for iron deficiency individuals. Flavonoids also interact with copper, manganese, and vitamin C [97,98]. They may exhibit antithyroid and goitrogenic activity. For example, quercetin and isoflavones inhibit iodothyronine deiodinase activity. High-dose isoflavones inhibit thyroid hormone biosynthesis, have estrogenic effects, and are goitrogenic [99,100]. Flavonoids may interfere with the absorption, tissue distribution, metabolism, and excretion of classical xenobiotics due to similar metabolic pathways. Notably, flavonoids interfere with all phase II enzymes, affecting the organism’s ability to detoxify endogenous and exogenous xenobiotics. For example, quercetin and kaempferol increase either the transcription or activity of the enzyme UDP-glucosyltransferase A1 [101].

Another vital factor to consider while reviewing in vitro studies is the effect of flavonoid distribution on local concentrations and drug interactions. For instance, quercetin and kaempferol inhibit CYP3A4 and, consequently, the metabolism of the Ca2+ channel blockers nifedipine and felodipine in human liver microsomes at concentrations >10 μmol/L [102]. On the other hand, quercetin did not inhibit CYP3A4 metabolism of the statin simvastatin in pigs. A possible explanation for this is a lower hepatic concentration than observed in vitro [103]. Flavonoids (with C5 hydroxy and methoxy groups [104,105]) inhibit ABC transposers. The inhibition has positive consequences for poorly absorbed drugs but may result in drug toxicities for low therapeutic index drugs [106].

Given these side effects, it has been concluded by some that whole fruits and vegetables are more beneficial to health than any single plant constituent [107]. On the flip side, overexpression of ABC transporters is one of the major mechanisms of multidrug resistance encountered during chemotherapy treatments. Cancer cells overexpress the ABC transporter, which pumps out anticancer drugs before they can have a significant effect. Thus, flavonoids can reduce drug resistance and thereby enhance the efficacy of chemotherapy. Moreover, several studies suggest that flavonoids sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapy [108,109]. Quercetin especially has promise, combined with vincristine, to increase breast cancer treatment efficacy [110]. Therefore, the potential of flavonoids as adjuncts in chemotherapy creates an additional incentive to investigate further their potential in counteracting CIPN, especially in studies involving humans.

Flavonoids have potential as therapeutic agents for preventing CIPN; however, many questions remain unanswered due to the lack of flavonoid studies with human subjects; e.g., what serum concentration must be achieved to get a significant therapeutic effect? Can this concentration be achieved by supplementing the diet with flavonoid-rich foods, or are intravenous injections a must? According to Mongiovi et al., increasing citrus fruit intake poses its own problems in patients undergoing chemotherapy—their results showed a positive association between citrus fruit intake (rich in flavonoids) and neuropathic pain symptoms [111], which may indicate potential detrimental interactions between flavonoids and other substances in citrus fruits. However, other studies evaluating the effects of diet on CIPN did not show this association [112], and thus more studies are required to further elucidate the effects of citrus fruits on CIPN symptoms. Furthermore, due to flavonoids’ potential side effects, an extensive cost-benefit analysis in humans is needed to determine whether a flavonoid-based treatment should be explored further.

Translating results obtained from mouse models to humans presents challenges of its own. Sex, differences in social structure, and variations in genotype and neuroanatomy all influence pain pathways and pain perception [3,113]. Due to the differences in symptoms experienced by humans and mice [113], the effects of flavonoids on humans are expected to be highly variable. Another complicating factor is that, unlike patients with CIPN, most mice in these studies do not have cancer. Furthermore, murine chemotherapy delivery methods may not match clinical ones; additionally, the sex of the animals does not match clinical demographics–studies with animals use mostly male mice, but there are many female cancer patients as well [3]. Also, in animal models, only acute (experienced within the first six months after treatment), not chronic (occurring about two years following treatment), neuropathic pain is studied [3]. Thus, the elucidated mechanisms are related to the acute phase only, and treatment with flavonoids may not have the same effect on chronic neuropathic pain [3]. The mechanisms of chronic neuropathic pain warrant more research in animal models, especially in the context of flavonoids. The symptoms of chronic neuropathic pain vary from those of the acute phase. While the acute phase is marked by dysesthesia, paraesthesia, and hyperesthesia, chronic neuropathy is mainly associated with sensory ataxia, insomnia, anxiety, depression, cognitive and functional deficits, and fall risk [10,11,114]. So far, only one study has assessed the effects of flavonoids on symptoms specific to chronic neuropathy: Chtourou et al. investigated cisplatin exposure to acetylcholinesterase, ATPase, and oxidative stress biomarkers and the potential association this may have on behavioral performance in aged rats. The protective mechanisms of the flavonoid naringin were also studied. While cisplatin decreased enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant activity in the hippocampus and raised levels of ROS, NO, MDA, and PCO, naringin reversed these effects and alleviated cisplatin-induced cognitive deficits (as seen by improved performance on the behavioral test administered) [115]. Flavonoids thus reverse anticancer drug-induced cognitive decline in chronic CIPN; in this light, their effects on the central nervous system merit further investigation. Also, flavonoids may hold promise in treating depression linked to chronic CIPN, since they are effective as antidepressants due to their antioxidant activity [116]. Furthermore, recent clinical results indicate that pediatric patients receiving azole antifungal treatment along with one-hour infusions of vincristine develop less severe peripheral neuropathy than patients receiving only vincristine. Similar studies should be conducted with flavonoids, in which isolated or mixed flavonoids are delivered during chemotherapy treatment to decrease the onset and severity of symptoms [117].

In short, increasing evidence indicates that flavonoids may alleviate the symptoms of both acute and chronic CIPN, increase the efficacy of chemotherapy, and reduce the cognitive dysfunction that results from it; thus, their side effects, effects in humans, and mechanisms of action are priorities for further investigation.

9. Conclusions

Flavonoids hold great promise in the management of CIPN. Investigating the mechanisms through which flavonoids act furthers the understanding of peripheral neuropathy and offers new methods to overcome it. The burden of CIPN and the promise of flavonoids encourages future research into their actions in humans, as well as their therapeutic index and side effects.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers13071576