BK polyomavirus nephropathy (BKVN) and allograft rejection are two closely-associated diseases on opposite ends of the immune scale in kidney transplant recipients. The principle of balancing the immune system remains the mainstay of therapeutic strategy.

- BK polyomavirus nephropathy

- kidney transplant

- acute rejection

- immunosuppressants

- tacrolimus

1. Introduction

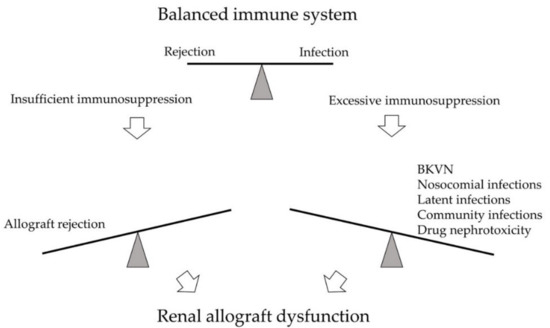

BK polyomavirus nephropathy (BKVN) and allograft rejection are two significant post-transplant complications on opposite ends of the immune spectrum (Figure 1). Parajuli et al. studied 3-year outcomes between these two diseases retrospectively. While BKVN and rejection are both prominent causes of kidney damage, renal function 3 years after diagnosis was worse for BKVN than for rejection [1]. The leading cause of BKVN is over-immunosuppression that reactivated the latent BK polyomavirus (BKPyV) within the recipient or reinforced BKPyV infection inside the allograft. No effective direct antiviral therapy is currently available; thus, since the first case was identified in 1971, immunosuppressant (IS) reduction remains the primary strategy for BKVN [2]. On the other hand, insufficient IS usage predisposes acute or chronic rejection, leading to graft function decline or graft loss as well.

Figure 1. The immune system of kidney transplant recipients is balanced between rejection and infection. Excessive immunosuppression may lead to infections, such as BK polyomavirus nephropathy (BKVN), nosocomial infections, latent infections, and community infections. Drug nephrotoxicity may also develop. On the opposite side, insufficient immunosuppression may result in allograft rejection. Both arms may cause significant kidney damage and renal allograft dysfunction.

Early diagnosis based on onset time and clinical manifestation is difficult due to similar clinical presentation of graft rejection and BKVN. Therefore, the highest principle in clinical practice is keeping a balance between rejection and infection [3].

2. About the BKPyV

BKPyV is a highly prevalent polyomavirus specific to the human host [4]. As a double-stranded DNA virus, its genome consists of the early coding region, late coding region, and a non-coding control region (NCCR) in between [5]. The early region usually codes for the replication proteins, including the small tumor antigens, the large tumor antigens (TAgs), and agnoprotein. The late region codes for structural proteins VP1, VP2, and VP3 [6]. The microRNAs expression was transcribed from the 3′ end of the TAgs and act as a regulator in BKPyV infection [7]. The NCCR contains the genome of promoters of the early and late regions, transcriptional start sites, and the origin of replication. It also provides binding sites for host cellular regulatory factors. NCCR variation exists between BKPyV isolates, and the rearranged forms of NCCR are associated with disease [8]. The high heterogeneity of NCCR allows for environmental adaptation and higher pathogenicity for disease progression [6].

Cellular immunity is critical for the immune response during BKPyV viremia and BKVN. Innate immune response serves as the first line of defense against the primary infection [9]. Dendritic cells are critical in the induction of adaptive immune response [10]. Womer et al. reported that the number of peripheral blood dendritic cells is lower in KTRs developed BKVN. They also revealed that KTRs with fewer dendritic cells before transplantation are more likely to be associated with BKVN [11]. Furthermore, BKPyV can decrease the natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity by inhibiting the identification of natural killer cells [12]. Other innate immune mediators are associated with renal inflammation [13]. Adaptive immune response develops after exposure to viral antigens. Humoral response works via neutralizing antibodies to defend the further viral infectious process. Studies showed seronegative recipients have higher risks in viremia and subsequent BKVN than seropositive recipients as humoral immunity may help limit BKPyV infection [14][15][16][17][18][19]. Meanwhile, recipients paired with seropositive donors have a higher post-transplant BK-specific-antibody titer than the seronegative donor group [20]. It means that BKPyV infection from the donor can induce the humoral immune response [21]. However, the virus can hide away from neutralization with a mutation in viral antibody receptors [22][23]. In this situation, latent viral reactivation can be well-controlled by antiviral memory T cells [4]. Cellular immunity offers more effective infection control because of pathogen detection and cytotoxicity [21]. Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are important, especially the polyfunctional BKPyV-specific T cells [24][25]. After kidney transplant, KTRs with viruria but no viremia have positive BKPyV-specific T cell response [26]. Conversely, there is no BKPyV-specific T cell response in KTRs with BKPyV viremia or BKVN [26][27][28][29][30]. Also, quick BK-specific T cell response was noted in the viremia-resolved group, while the response was only noted after reduced IS in the developed BKVN group [28][31]. These studies concluded that it is crucial for KTRs to reconstitute the BKPyV-specific T cells to fight against BKPyV infection.

During the first decade of childhood, the primary exposure to BKPyV, often with subclinical symptoms, resulted in 80–90% of adults developed antibodies against BKPyV [32][33]. The natural transmission route is still unknown [34]. After the primary infection, the virus remains latent in the kidney, peripheral-blood leukocytes, and possibly the brain [35]. The viral reactivation occurs while the host immunity is over-suppressed, resulting in viral replication with consequent tubular cell lysis and viruria. BKPyV replication ensues in the renal interstitium, leading to the destruction of the tubular capillary wall subsequently cross into the blood, causing viremia. Viral invasion of tissue progressively cause cell necrosis and tissue inflammation [36]. BKPyV reactivation presented as viremia usually happens in the first month post-transplant in KTRs. The incidence peaks around 28–31% at month 3 and month 12 after kidney transplantation, with cases rarely seen at month 18 [37][38]. In the KTR population, the incidence of BKPyV viruria is 30–40%, BKPyV viremia is 13%, and BKVN is 8% [39]. High-level BKPyV viruria progress to viremia after a median of 4 weeks, and approximately a median of 8 weeks later, viremia may lead to BKVN [40][41]. The clinical presentation of BKPyV infection may range from asymptomatic to progressive renal function decline, and others are incidental findings at protocol allograft biopsy [42]. The laboratory clues may be ranged from normal results to elevated serum creatinine, mild proteinuria (48%), or hematuria (19%) [43]. Without screening and treatment, the natural course of BKVN leads to 50% graft loss [44][45].

3. Screening and Diagnosis

Early diagnosis of BKVN usually results in better allograft survival than the advanced disease [43][46]. Due to limited treatment options, screening for BKPyV replication is recommended to avoid further kidney histologic involvement. Intensive screening by measuring blood BKPyV DNA can help patients at risk of BKVN preserve allograft function [47][48]. Monitoring of disease progression can be done through urine or blood polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The threshold value of urine viral load is 1 × 107 copies/mL. Viruria has a negative predictive value of 100% for BKVN, a positive predictive value of 31–67%, a sensitivity of 100%, and a specificity of 92–96% [48]. The threshold value of blood PCR is 1 × 104 copies/mL. Viremia has a negative predictive value of 100% for BKVN, a positive predictive value of 50–82%, a sensitivity of 100%, and a specificity of 88–96% [44][49]. The higher positive predictive value of viremia over viruria explains the 2019 Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice (AST-IDCOP), which suggested all KTRs should be screened for blood BKPyV DNA monthly until month 9 and then every 3 months until 2 years post-transplant [50]. Decoy cells, infected tubular epithelial cells identified by the urine cytology examination, are also standard screening methods but wholly depend on pathologists’ experience [49]. A Japanese study showed an increasing trend of decoy cells in the BK viremia group and suggested decoy cells can predict early BKPyV infection with continuous and careful monitoring [51]. Additionally, the 2009 KDIGO guideline indicated that in the case of unexplained allograft dysfunction or recent IS dosage increases, one should be cautious of BKPyV [52].

The diagnosis of BKVN relies on clinical judgment and pathological morphologic diagnosis [43]. Presumptive nephropathy, meaning a primary diagnosis without histologic confirmation, is defined as plasma BK viral DNA PCR load >10,000 copies/mL with urinary viral shedding for more than 2 weeks with or without renal function decline [53]. However, once suspected of renal function decline or possible acute rejection, renal biopsy should still be performed before reducing IS dosage [50]. Morphological diagnosis by light microscopy is limited due to similarities between early BKVN and other diagnoses such as acute rejection or calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) toxicity. Definite diagnosis of BKVN can be achieved through a cytopathic change of tubular epithelial cells combined with in situ hybridization against SV40 or Tag [54]. A unified diagnostic criterion is crucial for the comparability of different studies. However, previous morphology diagnosis classification is yet to provide statistical discriminative power for the clinical correlation sufficient enough to revise the classification [55]. AST-IDCOP revised the histological classification with a more detailed description of the degree of interstitial inflammation and the area of the biopsy tissue in 2013 [56]. Banff 2017 working group enrolled multicenter retrospective study analyzed confirmed BKVN systematically to develop a morphologic classification. Intrarenal BKPyV viral load and the Banff interstitial cortical fibrosis score are two independent factors with a significant correlation with clinical presentation and graft outcome [43]. AST-IDCOP 2019 recommended that histological findings of proven BKVN be reported based on AST-IDCOP 2013 and the Banff 2017 classification [50]. As for cases with coexisting BKVN and acute rejection, tubulitis and peritubular inflammation examination by immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy should be performed. The presence of endarteritis, fibrinoid vascular necrosis, glomerulitis, or C4d deposits along peritubular capillaries should be documented for the diagnosis of coexisting BKVN and acute rejection [57][58][59].

4. Novel Treatment for BKVN

4.1. Immune Therapy

4.1.1. Intravenous Immunoglobulin

The therapeutic mechanisms of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) for BKVN are not fully understood. Both donated and commercial IVIG contains IgG against various infectious diseases, including BKPyV neutralizing antibodies [60][61]. Meanwhile, IVIG has powerful indirect immunomodulatory effects [62][63]. Successful case series of viremia-lowering adjunctive therapy with IVIG had been reported after the failure of IS dose reduction and leflunomide administration [64][65][66]. An additional IVIG group presented cleared viremia and BKPyV immunohistochemistry evident from repeated tissue sampling [67]. A recent study showed significant increasing BKPyV genotype-specific neutralizing antibody titers in KTRs [68]. A retrospective study showed prophylactic IVIG in the early post-transplant phase was associated with a significantly lower incidence of both BKPyV viremia and BKVN in high-risk recipients [69]. Further randomized control trials are in expectancy in this field for more substantial evidence of IVIG efficacy.

On the other hand, IVIG is also the most common therapy for antibody-mediated rejection in adjunct with plasmapheresis and/or rituximab. The plasmapheresis removes the donor-specific antibodies, and IVIG exerts immunomodulatory effects on the antibodies. A meta-analysis included 21 articles of antibody-mediated rejection since 1950, showing insufficient evidence of all kinds of treatments due to each article’s small sample size [70]. Lefaucheur et al. conducted a randomized trial that compared IVIG only or IVIG combined plasmapheresis and rituximab. The high graft loss rate in IVIG alone group indicated IVIG by itself is not enough to prevent antibody-mediated rejection. Due to limited data and sample size of studies in this field, current management for antibody-mediated rejection remains plasmapheresis and IVIG combination therapy [71].

4.1.2. Cellular Therapy

The importance of cellular immunity toward BKPyV infection in transplant recipients has been recognized [72]. The BKPyV-specific T cell has drawn much attention, and its amount has a positive association with clearing BKPyV viremia in KTRs [30][73]. Failure of BKPyV-specific T cell to control viral replication due to IS overdose results in reactivation of BKPyV infection [74]. Thus, cellular therapy to regain immunity in recipients is a developing field in BKPyV immunotherapy. Owing to the advances in immunological techniques, adoptive T cell therapy was assisted by synthetic viral peptides to identify BKPyV and MHC antigens. Also, T cell expansion was performed by overlapping peptide pools. The enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay and tetramer staining can measure T cell responses. Many studies aimed to recognize adoptive T cell therapy’s safety and toxicity in vitro and in vivo. Papadopoulou et al. used overlapping peptide pools to generate virus-specific T cells for the commonly detected virus, including EBV, CMV, human herpesvirus 6 in vitro.

Meanwhile, these virus-specific T cells had successfully treated different viral infections, with a 94% response rate in 8 hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients without toxicity [75]. A phase II clinical trial showed that administration of BKPyV-specific T cells manufactured from a patient’s stem cell donor or unrelated donors could reduce symptomatic infection and BK viral load effectively in HSCT and solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients. A study enrolled 38 HSCT recipients and 3 SOT recipients who developed BKPyV viremia and/or hemorrhagic cystitis or nephropathy after transplant. The results showed clinical benefits; the overall response rate was 86% in the BK viremia group and 100% in the hemorrhagic cystitis group; 87% of patients in both groups were free of adverse effects, notably without a reduction in IS dose. This study supports further investigation in T cell therapy or even prophylaxis for BKVN [76].

4.2. Vaccine

There is no BKPyV vaccine currently, with most in the concept and design phase. Augmenting the humoral or cellular immune response to BKPyV is the central concept [77]. Due to cross-reaction did not exist between BKPyV serotypes, viral capsid protein aggregates instead of viral genetic components are the current approach in vaccine development [78][79]. Immunodominant peptides-modified BKPyV has been investigated [80]. Recent research found the multi-epitope vaccine with potential effectiveness may solve problems mention above for wide population use. Although the results are still in the experiment phase, it still displays impressive advances in this field [81].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/v13030487

References

- Parajuli, S.; Astor, B.C.; Kaufman, D.; Muth, B.; Mohamed, M.; Garg, N.; Djamali, A.; Mandelbrot, D.A. Which is more nephrotoxic for kidney transplants: BK nephropathy or rejection? Clin. Transplant. 2018, 32, e13216.

- Gardner, S.D.; Field, A.M.; Coleman, D.V.; Hulme, B. New human papovavirus (B.K.) isolated from urine after renal transplantation. Lancet 1971, 1, 1253–1257.

- Fishman, J.A. BK virus nephropathy--polyomavirus adding insult to injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 527–530.

- Ambalathingal, G.R.; Francis, R.S.; Smyth, M.J.; Smith, C.; Khanna, R. BK Polyomavirus: Clinical Aspects, Immune Regulation, and Emerging Therapies. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 503–528.

- Moens, U.; Van Ghelue, M.; Johannessen, M. Oncogenic potentials of the human polyomavirus regulatory proteins. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 1656–1678.

- Helle, F.; Brochot, E.; Handala, L.; Martin, E.; Castelain, S.; Francois, C.; Duverlie, G. Biology of the BKPyV: An Update. Viruses 2017, 9, 327.

- Broekema, N.M.; Imperiale, M.J. miRNA regulation of BK polyomavirus replication during early infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8200–8205.

- Cubitt, C.L. Molecular genetics of the BK virus. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2006, 577, 85–95.

- Comoli, P.; Binggeli, S.; Ginevri, F.; Hirsch, H.H. Polyomavirus-associated nephropathy: Update on BK virus-specific immunity. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2006, 8, 86–94.

- Drake, D.R., 3rd; Moser, J.M.; Hadley, A.; Altman, J.D.; Maliszewski, C.; Butz, E.; Lukacher, A.E. Polyomavirus-infected dendritic cells induce antiviral CD8(+) T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 4093–4101.

- Womer, K.L.; Huang, Y.; Herren, H.; Dibadj, K.; Peng, R.; Murawski, M.; Shraybman, R.; Patton, P.; Clare-Salzler, M.J.; Kaplan, B. Dendritic cell deficiency associated with development of BK viremia and nephropathy in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 2010, 89, 115–123.

- Bauman, Y.; Nachmani, D.; Vitenshtein, A.; Tsukerman, P.; Drayman, N.; Stern-Ginossar, N.; Lankry, D.; Gruda, R.; Mandelboim, O. An identical miRNA of the human JC and BK polyoma viruses targets the stress-induced ligand ULBP3 to escape immune elimination. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 9, 93–102.

- Ribeiro, A.; Wornle, M.; Motamedi, N.; Anders, H.J.; Grone, E.F.; Nitschko, H.; Kurktschiev, P.; Debiec, H.; Kretzler, M.; Cohen, C.D.; et al. Activation of innate immune defense mechanisms contributes to polyomavirus BK-associated nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2012, 81, 100–111.

- Ginevri, F.; De Santis, R.; Comoli, P.; Pastorino, N.; Rossi, C.; Botti, G.; Fontana, I.; Nocera, A.; Cardillo, M.; Ciardi, M.R.; et al. Polyomavirus BK infection in pediatric kidney-allograft recipients: A single-center analysis of incidence, risk factors, and novel therapeutic approaches. Transplantation 2003, 75, 1266–1270.

- Smith, J.M.; McDonald, R.A.; Finn, L.S.; Healey, P.J.; Davis, C.L.; Limaye, A.P. Polyomavirus nephropathy in pediatric kidney transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2004, 4, 2109–2117.

- Wunderink, H.F.; van der Meijden, E.; van der Blij-de Brouwer, C.S.; Mallat, M.J.; Haasnoot, G.W.; van Zwet, E.W.; Claas, E.C.; de Fijter, J.W.; Kroes, A.C.; Arnold, F.; et al. Pretransplantation Donor-Recipient Pair Seroreactivity Against BK Polyomavirus Predicts Viremia and Nephropathy After Kidney Transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2017, 17, 161–172.

- Bohl, D.L.; Storch, G.A.; Ryschkewitsch, C.; Gaudreault-Keener, M.; Schnitzler, M.A.; Major, E.O.; Brennan, D.C. Donor origin of BK virus in renal transplantation and role of HLA C7 in susceptibility to sustained BK viremia. Am. J. Transplant. 2005, 5, 2213–2221.

- Sood, P.; Senanayake, S.; Sujeet, K.; Medipalli, R.; Van-Why, S.K.; Cronin, D.C.; Johnson, C.P.; Hariharan, S. Donor and recipient BKV-specific IgG antibody and posttransplantation BKV infection: A prospective single-center study. Transplantation 2013, 95, 896–902.

- Abend, J.R.; Changala, M.; Sathe, A.; Casey, F.; Kistler, A.; Chandran, S.; Howard, A.; Wojciechowski, D. Correlation of BK Virus Neutralizing Serostatus With the Incidence of BK Viremia in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 2017, 101, 1495–1505.

- Andrews, C.A.; Shah, K.V.; Daniel, R.W.; Hirsch, M.S.; Rubin, R.H. A serological investigation of BK virus and JC virus infections in recipients of renal allografts. J. Infect. Dis. 1988, 158, 176–181.

- Lamarche, C.; Orio, J.; Collette, S.; Senecal, L.; Hebert, M.J.; Renoult, E.; Tibbles, L.A.; Delisle, J.S. BK Polyomavirus and the Transplanted Kidney: Immunopathology and Therapeutic Approaches. Transplantation 2016, 100, 2276–2287.

- Li, C.; Diprimio, N.; Bowles, D.E.; Hirsch, M.L.; Monahan, P.E.; Asokan, A.; Rabinowitz, J.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; Samulski, R.J. Single amino acid modification of adeno-associated virus capsid changes transduction and humoral immune profiles. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 7752–7759.

- Ciarlet, M.; Hoshino, Y.; Liprandi, F. Single point mutations may affect the serotype reactivity of serotype G11 porcine rotavirus strains: A widening spectrum? J. Virol. 1997, 71, 8213–8220.

- Renner, F.C.; Dietrich, H.; Bulut, N.; Celik, D.; Freitag, E.; Gaertner, N.; Karoui, S.; Mark, J.; Raatz, C.; Weimer, R.; et al. The risk of polyomavirus-associated graft nephropathy is increased by a combined suppression of CD8 and CD4 cell-dependent immune effects. Transplant. Proc. 2013, 45, 1608–1610.

- Schaenman, J.M.; Korin, Y.; Sidwell, T.; Kandarian, F.; Harre, N.; Gjertson, D.; Lum, E.L.; Reddy, U.; Huang, E.; Pham, P.T.; et al. Increased Frequency of BK Virus-Specific Polyfunctional CD8+ T Cells Predict Successful Control of BK Viremia After Kidney Transplantation. Transplantation 2017, 101, 1479–1487.

- Comoli, P.; Azzi, A.; Maccario, R.; Basso, S.; Botti, G.; Basile, G.; Fontana, I.; Labirio, M.; Cometa, A.; Poli, F.; et al. Polyomavirus BK-specific immunity after kidney transplantation. Transplantation 2004, 78, 1229–1232.

- Schachtner, T.; Stein, M.; Sefrin, A.; Babel, N.; Reinke, P. Inflammatory activation and recovering BKV-specific immunity correlate with self-limited BKV replication after renal transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2014, 27, 290–301.

- Schachtner, T.; Muller, K.; Stein, M.; Diezemann, C.; Sefrin, A.; Babel, N.; Reinke, P. BK virus-specific immunity kinetics: A predictor of recovery from polyomavirus BK-associated nephropathy. Am. J. Transplant. 2011, 11, 2443–2452.

- Comoli, P.; Hirsch, H.H.; Ginevri, F. Cellular immune responses to BK virus. Curr. Opin. Organ. Transplant. 2008, 13, 569–574.

- Schachtner, T.; Stein, M.; Babel, N.; Reinke, P. The Loss of BKV-specific Immunity From Pretransplantation to Posttransplantation Identifies Kidney Transplant Recipients at Increased Risk of BKV Replication. Am. J. Transplant. 2015, 15, 2159–2169.

- Ozsancak, C.; Auzou, P.; Dujardin, K.; Quinn, N.; Destee, A. Orofacial apraxia in corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy and Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol 2004, 251, 1317–1323.

- Stolt, A.; Sasnauskas, K.; Koskela, P.; Lehtinen, M.; Dillner, J. Seroepidemiology of the human polyomaviruses. J. Gen. Virol 2003, 84 Pt 6, 1499–1504.

- Egli, A.; Infanti, L.; Dumoulin, A.; Buser, A.; Samaridis, J.; Stebler, C.; Gosert, R.; Hirsch, H.H. Prevalence of polyomavirus BK and JC infection and replication in 400 healthy blood donors. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 199, 837–846.

- Virgin, H.W.; Wherry, E.J.; Ahmed, R. Redefining chronic viral infection. Cell 2009, 138, 30–50.

- Peinemann, F.; de Villiers, E.M.; Dorries, K.; Adams, O.; Vogeli, T.A.; Burdach, S. Clinical course and treatment of haemorrhagic cystitis associated with BK type of human polyomavirus in nine paediatric recipients of allogeneic bone marrow transplants. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2000, 159, 182–188.

- Low, J.; Humes, H.D.; Szczypka, M.; Imperiale, M. BKV and SV40 infection of human kidney tubular epithelial cells in vitro. Virology 2004, 323, 182–188.

- Koukoulaki, M.; Grispou, E.; Pistolas, D.; Balaska, K.; Apostolou, T.; Anagnostopoulou, M.; Tseleni-Kotsovili, A.; Hadjiconstantinou, V.; Paniara, O.; Saroglou, G.; et al. Prospective monitoring of BK virus replication in renal transplant recipients. Transpl Infect. Dis. 2009, 11, 1–10.

- Thakur, R.; Arora, S.; Nada, R.; Minz, M.; Joshi, K. Prospective monitoring of BK virus reactivation in renal transplant recipients in North India. Transpl Infect. Dis. 2011, 13, 575–583.

- Hirsch, H.H.; Knowles, W.; Dickenmann, M.; Passweg, J.; Klimkait, T.; Mihatsch, M.J.; Steiger, J. Prospective study of polyomavirus type BK replication and nephropathy in renal-transplant recipients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 488–496.

- Brennan, D.C.; Agha, I.; Bohl, D.L.; Schnitzler, M.A.; Hardinger, K.L.; Lockwood, M.; Torrence, S.; Schuessler, R.; Roby, T.; Gaudreault-Keener, M.; et al. Incidence of BK with tacrolimus versus cyclosporine and impact of preemptive immunosuppression reduction. Am. J. Transplant. 2005, 5, 582–594.

- Schwarz, A.; Linnenweber-Held, S.; Heim, A.; Framke, T.; Haller, H.; Schmitt, C. Viral Origin, Clinical Course, and Renal Outcomes in Patients With BK Virus Infection After Living-Donor Renal Transplantation. Transplantation 2016, 100, 844–853.

- Kahan, A.V.; Coleman, D.V.; Koss, L.G. Activation of human polyomavirus infection-detection by cytologic technics. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1980, 74, 326–332.

- Nickeleit, V.; Singh, H.K.; Randhawa, P.; Drachenberg, C.B.; Bhatnagar, R.; Bracamonte, E.; Chang, A.; Chon, W.J.; Dadhania, D.; Davis, V.G.; et al. The Banff Working Group Classification of Definitive Polyomavirus Nephropathy: Morphologic Definitions and Clinical Correlations. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 680–693.

- Hirsch, H.H. Polyomavirus BK nephropathy: A (re-)emerging complication in renal transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2002, 2, 25–30.

- Randhawa, P.S.; Demetris, A.J. Nephropathy due to polyomavirus type BK. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 1361–1363.

- Costa, J.S.; Ferreira, E.; Leal, R.; Bota, N.; Romaozinho, C.; Sousa, V.; Marinho, C.; Santos, L.; Macario, F.; Alves, R.; et al. Polyomavirus Nephropathy: Ten-Year Experience. Transplant. Proc. 2017, 49, 803–808.

- Hirsch, H.H.; Vincenti, F.; Friman, S.; Tuncer, M.; Citterio, F.; Wiecek, A.; Scheuermann, E.H.; Klinger, M.; Russ, G.; Pescovitz, M.D.; et al. Polyomavirus BK replication in de novo kidney transplant patients receiving tacrolimus or cyclosporine: A prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Am. J. Transplant. 2013, 13, 136–145.

- Schaub, S.; Hirsch, H.H.; Dickenmann, M.; Steiger, J.; Mihatsch, M.J.; Hopfer, H.; Mayr, M. Reducing immunosuppression preserves allograft function in presumptive and definitive polyomavirus-associated nephropathy. Am. J. Transplant. 2010, 10, 2615–2623.

- Viscount, H.B.; Eid, A.J.; Espy, M.J.; Griffin, M.D.; Thomsen, K.M.; Harmsen, W.S.; Razonable, R.R.; Smith, T.F. Polyomavirus polymerase chain reaction as a surrogate marker of polyomavirus-associated nephropathy. Transplantation 2007, 84, 340–345.

- Hirsch, H.H.; Randhawa, P.S.; on behalf of AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. BK polyomavirus in solid organ transplantation-Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin. Transplant. 2019, 33, e13528.

- Yamada, Y.; Tsuchiya, T.; Inagaki, I.; Seishima, M.; Deguchi, T. Prediction of Early BK Virus Infection in Kidney Transplant Recipients by the Number of Cells With Intranuclear Inclusion Bodies (Decoy Cells). Transplant. Direct. 2018, 4, e340.

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Transplant Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2009, 9 (Suppl. 3), S1–S155.

- Sawinski, D.; Goral, S. BK virus infection: An update on diagnosis and treatment. Nephrol Dial. Transplant. 2015, 30, 209–217.

- Drachenberg, C.B.; Beskow, C.O.; Cangro, C.B.; Bourquin, P.M.; Simsir, A.; Fink, J.; Weir, M.R.; Klassen, D.K.; Bartlett, S.T.; Papadimitriou, J.C. Human polyoma virus in renal allograft biopsies: Morphological findings and correlation with urine cytology. Hum. Pathol. 1999, 30, 970–977.

- Nankivell, B.J.; Renthawa, J.; Sharma, R.N.; Kable, K.; O’Connell, P.J.; Chapman, J.R. BK Virus Nephropathy: Histological Evolution by Sequential Pathology. Am. J. Transplant. 2017, 17, 2065–2077.

- Hirsch, H.H.; Randhawa, P.; the AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. BK polyomavirus in solid organ transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2013, 13 (Suppl. 4), 179–188.

- Bracamonte, E.; Leca, N.; Smith, K.D.; Nicosia, R.F.; Nickeleit, V.; Kendrick, E.; Furmanczyk, P.S.; Davis, C.L.; Alpers, C.E.; Kowalewska, J. Tubular basement membrane immune deposits in association with BK polyomavirus nephropathy. Am. J. Transplant. 2007, 7, 1552–1560.

- Hever, A.; Nast, C.C. Polyoma virus nephropathy with simian virus 40 antigen-containing tubular basement membrane immune complex deposition. Hum. Pathol. 2008, 39, 73–79.

- McGregor, S.M.; Chon, W.J.; Kim, L.; Chang, A.; Meehan, S.M. Clinical and pathological features of kidney transplant patients with concurrent polyomavirus nephropathy and rejection-associated endarteritis. World J. Transplant. 2015, 5, 292–299.

- Randhawa, P.S.; Schonder, K.; Shapiro, R.; Farasati, N.; Huang, Y. Polyomavirus BK neutralizing activity in human immunoglobulin preparations. Transplantation 2010, 89, 1462–1465.

- Randhawa, P.; Pastrana, D.V.; Zeng, G.; Huang, Y.; Shapiro, R.; Sood, P.; Puttarajappa, C.; Berger, M.; Hariharan, S.; Buck, C.B. Commercially available immunoglobulins contain virus neutralizing antibodies against all major genotypes of polyomavirus BK. Am. J. Transplant. 2015, 15, 1014–1020.

- Sener, A.; House, A.A.; Jevnikar, A.M.; Boudville, N.; McAlister, V.C.; Muirhead, N.; Rehman, F.; Luke, P.P. Intravenous immunoglobulin as a treatment for BK virus associated nephropathy: One-year follow-up of renal allograft recipients. Transplantation 2006, 81, 117–120.

- Gelfand, E.W. Intravenous immune globulin in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 2015–2025.

- Vu, D.; Shah, T.; Ansari, J.; Naraghi, R.; Min, D. Efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of persistent BK viremia and BK virus nephropathy in renal transplant recipients. Transplant. Proc. 2015, 47, 394–398.

- Shah, T.; Vu, D.; Naraghi, R.; Campbell, A.; Min, D. Efficacy of Intravenous Immunoglobulin in the Treatment of Persistent BK Viremia and BK Virus Nephropathy in Renal Transplant Recipients. Clin. Transpl. 2014, 47, 109–116.

- Matsumura, S.; Kato, T.; Taniguchi, A.; Kawamura, M.; Nakazawa, S.; Namba-Hamano, T.; Abe, T.; Nonomura, N.; Imamura, R. Clinical Efficacy of Intravenous Immunoglobulin for BK Polyomavirus-Associated Nephropathy After Living Kidney Transplantation. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2020, 16, 947–952.

- Kable, K.; Davies, C.D.; O’Connell, P.J.; Chapman, J.R.; Nankivell, B.J. Clearance of BK Virus Nephropathy by Combination Antiviral Therapy With Intravenous Immunoglobulin. Transplant. Direct. 2017, 3, e142.

- Velay, A.; Solis, M.; Benotmane, I.; Gantner, P.; Soulier, E.; Moulin, B.; Caillard, S.; Fafi-Kremer, S. Intravenous Immunoglobulin Administration Significantly Increases BKPyV Genotype-Specific Neutralizing Antibody Titers in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63.

- Miller, R.J.H.; Kwiecinski, J.; Shah, K.S.; Eisenberg, E.; Patel, J.; Kobashigawa, J.A.; Azarbal, B.; Tamarappoo, B.; Berman, D.S.; Slomka, P.J.; et al. Coronary computed tomography-angiography quantitative plaque analysis improves detection of early cardiac allograft vasculopathy: A pilot study. Am. J. Transplant. 2020, 20, 1375–1383.

- Wan, S.S.; Ying, T.D.; Wyburn, K.; Roberts, D.M.; Wyld, M.; Chadban, S.J. The Treatment of Antibody-Mediated Rejection in Kidney Transplantation: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transplantation 2018, 102, 557–568.

- Lefaucheur, C.; Nochy, D.; Andrade, J.; Verine, J.; Gautreau, C.; Charron, D.; Hill, G.S.; Glotz, D.; Suberbielle-Boissel, C. Comparison of combination Plasmapheresis/IVIg/anti-CD20 versus high-dose IVIg in the treatment of antibody-mediated rejection. Am. J. Transplant. 2009, 9, 1099–1107.

- Rovescalli, A.C.; Brunello, N.; Franzetti, C.; Racagni, G. Interaction of putative endogenous tryptolines with the hypothalamic serotonergic system and prolactin secretion in adult male rats. Neuroendocrinology 1986, 43, 603–610.

- Rao, Z.; Huang, Z.; Song, T.; Lin, T. A lesson from kidney transplantation among identical twins: Case report and literature review. Transpl. Immunol. 2015, 33, 27–29.

- Iturriza-Gomara, M.; O’Brien, S.J. Foodborne viral infections. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 29, 495–501.

- Papadopoulou, A.; Gerdemann, U.; Katari, U.L.; Tzannou, I.; Liu, H.; Martinez, C.; Leung, K.; Carrum, G.; Gee, A.P.; Vera, J.F.; et al. Activity of broad-spectrum T cells as treatment for AdV, EBV, CMV, BKV, and HHV6 infections after HSCT. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 242ra83.

- Nelson, A.S.; Heyenbruch, D.; Rubinstein, J.D.; Sabulski, A.; Jodele, S.; Thomas, S.; Lutzko, C.; Zhu, X.; Leemhuis, T.; Cancelas, J.A.; et al. Virus-specific T-cell therapy to treat BK polyomavirus infection in bone marrow and solid organ transplant recipients. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 5745–5754.

- Kaur, A.; Wilhelm, M.; Wilk, S.; Hirsch, H.H. BK polyomavirus-specific antibody and T-cell responses in kidney transplantation: Update. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 32, 575–583.

- Teunissen, E.A.; de Raad, M.; Mastrobattista, E. Production and biomedical applications of virus-like particles derived from polyomaviruses. J. Control. Release 2013, 172, 305–321.

- Pastrana, D.V.; Ray, U.; Magaldi, T.G.; Schowalter, R.M.; Cuburu, N.; Buck, C.B. BK polyomavirus genotypes represent distinct serotypes with distinct entry tropism. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 10105–10113.

- Husseiny, M.I.; Lacey, S.F. Development of infectious recombinant BK virus. Virus Res. 2011, 161, 150–161.

- Kesherwani, V.; Tarang, S. An immunoinformatic approach to universal therapeutic vaccine design against BK virus. Vaccine 2019, 37, 3457–3463.