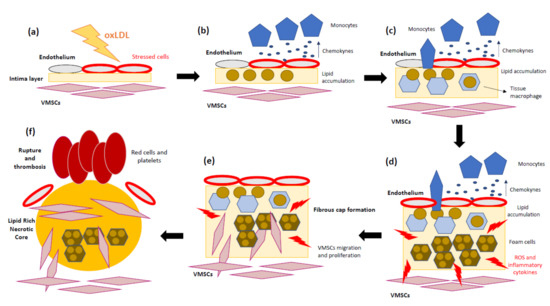

Atherosclerosis is recognized as a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the accumulation of lipids, mainly cholesterol, and other components, such as fatty substances, cellular waste products, calcium, and fibrin within the arterial wall.

- atherosclerosis

- mitochondria

- inflammation

- inflammasome

- reactive oxygen species

- NLRP3

1. Mitochondria and Inflammation

Mitochondria are one of the most multifunctional organelles in the cell [1]. Their major function as cell energy generators has been extensively studied. In addition, mitochondria are involved in many cell processes, such as steroid biosynthesis [2], calcium [3] and iron [4] homeostasis, immune cell activation [5], redox signaling [6], apoptosis [7], and inflammation [8].

The first line of defense of metazoan organisms to deal with infection and/or tissue damage is the innate immunity response [9]. During infection, inflammation is commonly caused by microbial compounds, known as pathogen-associated molecule patterns (PAMPs), for instance, lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from bacteria or viral RNA. On the other hand, during tissue damage, inflammation is activated by intracellular molecules that are not usually exposed to the immune system. However, during cell stress or damage, they are secreted into the cytoplasm or leak into the extracellular environment. These molecules are called damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs).

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), are sensors that recognize both PAMPs and DAMPs. The ligation of PRRs by DAMPs induces intracellular signaling pathways that promote the expression and activation of several pro-inflammatory mechanisms whose regulation and response depend on the PRR and cell type. Curiously, some PRR can ligate with both DAMPs and PAMPs [10]. The stimulation of a PRR through its ligands triggers the activation of the immune system [11]. For instance, DAMPs such as uric acid promote dendritic cell maturation [12] while PAMPs such as chitin, a major component of the fungal cell wall, can be recognized by epidermal cells for chemokine secretion and leukocyte recruitment [13]. Normally, the sensing of PAMPs or DAMPs by PRRs leads to the nuclear translocation of transcription factors, including the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), which upregulate the transcription of genes involved in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, type I interferons (IFNs), chemokines and antimicrobial proteins, proteins involved in the modulation of PRR signaling, and inflammasome proteins [14].

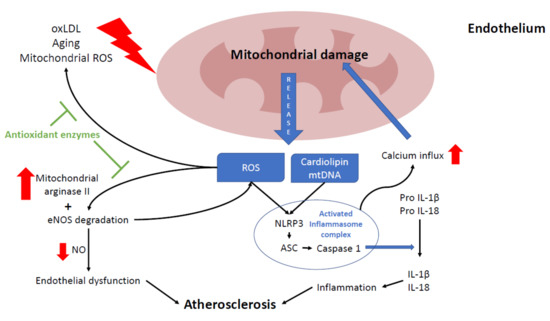

The close similarity between prokaryotic DNA and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is an important factor for understanding the role of mitochondria in inflammation, as well as supporting evidence for the endosymbiosis theory [15]. mtDNA is a double-stranded, circular molecule that contains a high concentration of cytosine-guanine sequences or CpG islands. mtDNA is released by damaged cells and can be sensed by a PRR, the Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9), which is the receptor for CpG motifs in DNA [16]. This interaction leads to the NF-κB activation signaling pathway and, consequently, the induction of multiple pro-inflammatory genes [17,18]. In addition, mtDNA can activate the nod like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome [19], thereafter promoting caspase-1 activation, the processing of interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and interleukin 18 (IL-18), and eventually, cell death. Mitochondrial dysfunction may also amplify the activation of NLRP3 by mitochondrial ROS production. It is well known that these oxygen species bind and activate NLRP3 in a continuous vicious cycle where NLRP3 will also promote ROS generation [20]. The stimulator of interferon genes (STING) inflammatory pathway can also be activated via mtDNA by the protein cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) [21]. In this case, it will result in increased interferon-regulatory factor 3 (IRF3)-dependent gene expression, including induction of type I interferons. In summary, mtDNA is able to activate the innate immune signaling pathways by acting as a danger signal released from mitochondria into the cytoplasm, which warns the cell of serious damage.

Mitochondria are also necessary for the oligomerization of retinoic-acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLR), which are involved in the recognition of the viral double-stranded RNA PAMP. After viral RNA is detected by RIG-I in the cytosol, it interacts with the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS), located in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Then MAVS is activated and recruits the machinery involved in type I interferon production [8,22]. MAVS also participates in other signal pathways related with mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS) and inflammation [23,24]. Mitochondrial activity is also necessary for the Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling cascades: activated TLRs can signal through tumor-necrosis-factor-receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF), which translocates to the mitochondrion and ubiquitinates the mitochondrial protein evolutionarily conserved signaling intermediate in Toll pathway (ECSIT). This causes the mitochondrion to both move to the phagosome and enhance mtROS production, resulting in direct antimicrobial killing [25,26]. For instance, TLR1, TLR2, and TLR4 recognize bacterial tri-acylated lipopeptides and LPS in order to enhance ROS production in the phagosome (oxidative burst of macrophages), which is required for its antimicrobial activity [27].

2. Atherosclerosis as a Representative Inflammatory Disease

3. The Role of Mitochondria in Atherosclerosis

Mitochondria are the major source of energy in the cell through their mitochondrial respiratory chain (MRC). Almost all the energy released during mitochondrial electron transport is used for ATP synthesis, making MRC one of the most refined processes in nature. However, just a small percentage of electrons leak to oxygen, resulting in the generation of superoxide radicals, which are considered mitochondrial ROS [76]. There are alternative sources of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide radical anion (O2−), such as the mitochondrial outer membrane enzymes monoamine oxidase [77] and aldehyde oxidase [78].

ROS are necessary for the cell as secondary signaling agents [79], and they are regulated by numerous antioxidant molecules and proteins. In fact, ROS are gaining relevance in many research fields since it is now known that they can function as signaling molecules and in protein modification processes [80,81]. This mechanism is carried out by the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase enzymes, whose sole function is the formation of ROS. Seven NADPH oxidases are expressed in the human body, namely Nox1–Nox5 and Duox1 and Duox2 [82]. Each one has different functions, for instance, Nox2 is involved in host defense [81], Nox4 plays a role in cellular homeostasis and cancer [83], and Nox5 is related with cardiovascular health [84].

In mitochondria, O2- is rapidly transformed into H2O2 by manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase (SOD2), followed by its conversion into water by glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1) [85]. Under stress or pathological conditions, ROS are released from different sources, such as the activity of xanthine oxidase, lipoxygenase, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase, uncoupling of nitric oxide (NO) synthase, and the leakage of electrons at mitochondrial complexes I and III during oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) [86]. Therefore, damaged mitochondria produce large amounts of ROS, which in turn can affect the function of adjacent mitochondria. This continuous oxidative cycle is named ROS-induced ROS and is a common phenomenon based on the amplification of ROS production that induces further mitochondrial and cell dysfunction [87]. Interestingly, it has been reported that cytochrome c, a heme-containing protein mainly involved in mitochondrial electron transport, is involved in the ROS-induced ROS process [88].

Under normal physiological conditions, ROS damage is controlled by antioxidant molecules, such as glutathione, carotenoids, coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), and antioxidant enzymes. However, in atherosclerosis, when ROS surpass the antioxidant barriers, the increased oxidative stress in the arterial endothelium triggers the appearance of oxLDL [89]. In addition, this process drives an ROS-induced ROS mechanism, increasing mitochondrial ROS and promoting atherosclerosis progression [90]. An interesting study has shown that the accumulation of ROS also promotes DNA fragmentation and increases monocytes’ apoptosis in normocholesterolemic old mice, which is worsened in age-matched atherosclerotic mice, indicating that increased ROS may promote the aggravation of age-related atherosclerosis [91]. In addition, the aggregation of LDL-C in the arterial wall induces ROS production and enhances atherosclerosis progression in hypercholesterolemic mice [92]. Moreover, mice with transplanted bone marrow with mitochondrial dysfunction showed increased ROS levels and apoptotic cells, which contributed to the development of pro-atherosclerotic aortic lesions [93,94].

There are several factors related with ROS production in atherosclerosis, including sex, age, exercise, diet, obesity, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. Although ROS could act as the second messenger in various cellular pathways, their accumulation can cause the activation of inflammatory cytokines [95]. Moreover, severe DNA damage caused by excessive ROS overactivates the poly(Adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) pathway, which leads to the functional impairment or death of VSMCs and vascular endothelial cells (VECs) through ATP and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) depletion and, consequently, increases inflammation. In addition, mitochondrial malfunction results in ROS overproduction, which induces the oxidation of lipids, nucleic acids, and proteins, which eventually leads to severe cellular damage. Enhanced ROS production causes endothelial dysfunction, vascular inflammation, and accumulation of oxLDL in the arterial wall, which are responsible for the formation of the early plaque and its growth [96]. Taken together, these findings indicate that mitochondrial dysfunction, in combination with oxLDL, originates a continuous cycle associated with inflammation that will eventually lead to atheroma formation.

Apart from ROS, mitochondria are also able to release mitochondrial-derived damage-associated molecular patterns (mito-DAMPs), which show immunogenic capacity when misplaced or imbalanced. Mito-DAMPs are known as early inflammatory modulators in response to cellular stress, promoting the chemoattraction of immune cells [97]. Although mito-DAMPs could have a positive effect on tissue injury recovery [98], aberrant and chronical mito-DAMP release could lead to severe mitochondrial dysfunction and continuous inflammatory processes, leading to pathological disorders [97,98,99].

One proposed mitochondrial mechanism to enhance cell survival and reduce atherosclerotic damage is the release of humanin, a prominent member of a newly discovered family of mitochondrial-derived peptides expressed from an open reading frame of mitochondrial 16S rRNA. This mitochondrial-encoded peptide has been shown to play a role in preventing cell death among various tissues [100,101,102], including the endothelium [103]. Zacharias et al. demonstrated that humanin is expressed in the endothelium, smooth muscles, and macrophages during atherosclerosis and that its administration ex vivo results in decreased ROS production and apoptosis after oxLDL exposure of human aortic endothelial cells [104]. They also showed that humanin exerts a protective effect on endothelial function and atherosclerotic progression in ApoE-deficient mice [105]. The specific signal leading to a higher expression of humanin in atherosclerosis is unknown. Since apoptosis is a natural process in late-stage atherosclerosis contributing to the formation of a necrotic core and unstable plaque, the expression of humanin might be a defense mechanism to slow down the progression of the disease. Although unstable plaques present higher humanin levels, this compensatory response may not be sufficient to withstand sustained damage and, consequently, eventual ischemic events might arise [104].

3.1. Focusing on the Endothelial Origin of Atherosclerosis

3.2. Mitochondria and NLRP3 Inflammasome

3.3. Mitochondrial Mutations and Atherogenesis

The appearance of atherosclerosis in mitochondrial diseases may result from a primary pathological mechanism or as a consequence of a secondary mechanism associated with diabetes, arterial hypertension, or hyperlipidemia [152]. Most frequently, patients harboring mutations in mtDNA may develop primary mitochondrial atherosclerosis. Although the precise mechanism is not clear, it is believed that primary mitochondrial atherosclerosis results from increased oxidative stress, mitophagy alterations, energy deficiency, accumulation of toxic metabolites, or NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Thus, atherosclerosis in mitochondrial disorders may occur even in the absence of recognized atherosclerosis risk factors, suggesting that atherosclerosis can be a primary consequence of mitochondrial defect. However, there is still no direct evidence relating mitochondrial dysfunction to atherosclerosis progression [152].

Mitochondria could be directly linked to atherosclerosis in several ways. For this reason, mitochondrial dysfunction or excessive ROS caused by mitochondrial genetic mutations could promote atherogenesis [152]. In fact, it has been demonstrated that some mitochondrial mutations may lead to chronic inflammatory processes associated with NLRP3 activation [153], a key pathogenic factor in atherosclerosis development. This group of genetic alterations and the associated mitochondrial dysfunction may enhance the mitochondrial release of mtDNA and other mitochondrial DAMPs, initiating an inflammatory response through NLRP3 inflammasome activation [154].

Mitochondrial ROS have been suggested to be the origin of an increased mutation rate in mtDNA, one that is up to 15 times higher than that of nuclear DNA [155]. On the other hand, the presence of multiple copies of mtDNA in single cells explains the phenomenon of heteroplasmy, which refers to the variable proportion of wild-type and mutant mtDNA copies within the cell or the tissue [156]. This proportion between different mtDNA varies with aging and is dependent on the cell type and the tissue [157]. The assessment of the mtDNA heteroplasmic mutation load, as well as the mtDNA copy number, is a plausible way to explain the focality of atherosclerotic lesions [158,159]. Thus, cells possessing the level of heteroplasmy exceeding a certain threshold may exhibit mitochondrial dysfunction, whereas in the adjacent cells with a lower mutational load, the respiratory chain remains fully functional [160]. A similar mosaic pattern can be observed in atherosclerosis, where healthy areas of arterial wall coexist with regions bearing different types of atherosclerotic lesions [161,162].

Nowadays, several studies assume a connection between mtDNA mutations and atherosclerosis [163,164,165]. These studies were performed using leukocytes and arterial wall samples from atherosclerotic human patients. Most mutations were related to mitochondrial ribosomes, mitochondrial transfer RNA, and various mitochondrial-encoded respiratory complex subunits. It has been proposed that the presence of these mutations promotes mitochondrial dysfunction and therefore ROS production, which enhances the appearance of atherosclerotic plaques and increases the thickness of the intima and medial layers in carotid arteries [164]. Interestingly, Sazonova et al. discovered the presence of several mtDNA mutations associated with patients presenting with carotid atherosclerosis as well as two single-nucleotide substitutions that negatively correlate with atherosclerotic lesions [164]. It has been proposed that these mutations can be biomarkers for assessing predisposition to this disease.

Despite the available evidence, there is no established consensus on the importance of heteroplasmy in atherosclerosis [166]. The main hypothesis suggests that a primary defect of the respiratory chain or OXPHOS system may be associated with reduced energy production that can ultimately lead to the collapse of cell energy metabolism. Uncoupling of the electron transfer from ATP synthesis results in the excess generation of ROS, leading to widespread cellular injury and vascular damage [167]. In addition, ROS overproduction may enhance the mtDNA mutation rate and, as a consequence, further increase ROS production [168].

One of the mechanisms that enable cells to cope with heteroplasmy and mitochondrial dysfunction is mitophagy. Mitophagy surveils the mitochondrial population, removing unnecessary and/or impaired organelles. [169]. This process requires high energy and regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation [18,170]. Therefore, the defective removal of damaged mitochondria leads to the hyperactivation of inflammatory signaling pathways and, subsequently, to chronic local or systemic inflammation [171,172], which may result in focal or generalized atherosclerosis [173]. In agreement with this assumption, in vitro inhibition of mitophagy in a primary culture of human monocyte-derived macrophages increased pro-inflammatory response in the form of up-regulation of the IL-1β gene [174].

However, it is not clear whether it is the increased mitochondrial ROS caused by atherosclerosis throughout lifetime that increases somatic mtDNA mutations or if it is previous maternally inherited mtDNA mutations that promote atherosclerosis [166]. Overall, the mechanism behind the role of heteroplasmic mtDNA variants in the development of atherosclerosis is still not completely understood.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biomedicines9030258