Vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) are primary regulators of blood and lymphatic vessels. Hemangiogenic VEGFs (VEGF-A, PlGF, and VEGF-B) target mostly blood vessels, while the lymphangiogenic VEGFs (VEGF-C and VEGF-D) target mostly lymphatic vessels. Blocking VEGF-A is used today to treat several types of cancer (“antiangiogenic therapy”). However, in other diseases, it would be beneficial to do the opposite, namely to increase the activity of VEGFs. For example, VEGF-A could generate new blood vessels to protect from heart disease, and VEGF-C could generate new lymphatics to counteract lymphedema. Clinical trials that tried to stimulate blood vessel growth in ischemic diseases have been disappointing so far, and the first clinical trials targeting the lymphatic vasculature have progressed to phase II. Antiangiogenic drugs targeting VEGF-A such as bevacizumab or aflibercept neutralize the growth factor directly. However, since VEGF-C and VEGF-D are produced as inactive precursors, novel drugs against the lymphangiogenic VEGFs could also target the enzymatic activation of VEGF-C and VEGF-D. Because of the delicate balance between too much and too little vascular growth, a detailed understanding of the activation of the VEGF-C and VEGF-D is needed before such concepts can be converted into safe and efficacious therapies.

- vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs)

- VEGF-C

- VEGF-D

- VEGF-A

- vascular biology

- angiogenesis

- lymphangiogenesis

- antiangiogenic therapy

- proangiogenic therapy

- blood vessels

- lymphatic vessels

1. Introduction

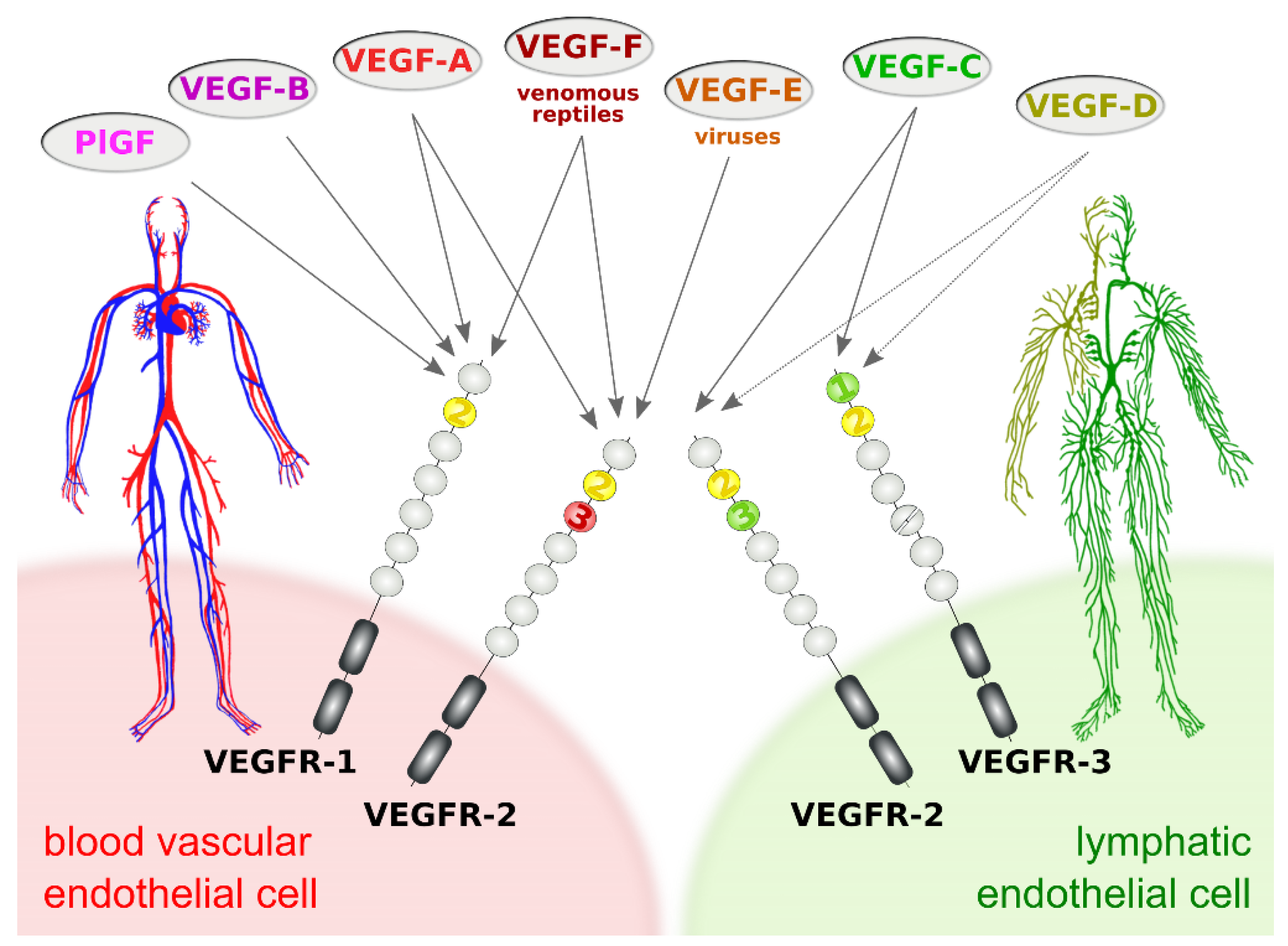

In vertebrates, the family of vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) typically comprises five genes: VEGF-A (in older literature often referred to simply as “VEGF”), placenta growth factor (PlGF), VEGF-B, VEGF-C, and VEGF-D. In addition to these orthodox VEGFs, several genes coding for VEGF-like molecules have been discovered in some members of the poxvirus and iridovirus families (collectively named VEGF-E) [1][2][3][4] and in venomous reptiles (collectively named VEGF-F) [5]. In vertebrates, the VEGF growth factors are central to the development and maintenance of the cardiovascular system and the lymphatic system. Non-vertebrates also feature VEGF-like molecules [6][7], but their functions are less well defined.

The subdivision of the vertebrate vascular system into the cardiovascular and the lymphatic system is reflected at the molecular level by a subdivision of the VEGF family into VEGFs acting primarily on blood vessels (VEGF-A, PlGF, and VEGF-B) and VEGFs acting mostly on lymphatic vessels (VEGF-C and VEGF-D). This specificity results from the expression pattern of the three VEGF receptors (VEGFRs). VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 are expressed on blood vascular endothelial cells (BECs), while lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) express VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) act on blood vessels and/or lymphatic vessels depending on their affinities towards VEGF receptors 1, -2, and -3. VEGFR-2 is expressed on both blood and lymphatic endothelium. In principle, growth factors that do activate VEGFR-2 can promote both the growth of blood vessels (angiogenesis) and lymphatic vessels (lymphangiogenesis). VEGF-E and VEGF-F are not of human origin: VEGF-E genes are found in viral genomes, and VEGF-F is a snake venom component. All receptor-growth factor interactions require the extracellular domain 2 of the VEGF receptors (shown in yellow) [8][9][10][11]. Domain 3 of VEGFR-2 is important for the interaction of VEGFR-2 with both VEGF-A [9] and VEGF-C [10], and domain 1 of VEGFR-3 is important for the interaction of VEGF-C with VEGFR-3 [11].

The biology of the VEGFs and their signaling pathways has been extensively discussed elsewhere [12][13]. From all VEGF family members, only VEGF-A and VEGF-C are essential in the sense that constitutive ablation of their genes in mice results in embryonic lethality [14][15]. VEGF-A levels are so crucial that even heterozygous mice are not viable. In fact, VEGFA was the first gene where the deletion of a single allele was shown to be embryonically lethal [14][15]. While the primary function and importance of the cardiovascular system — oxygen and nutrient distribution — are also obvious to the layperson, the tasks of the lymphatic system escape even some life science professionals. Its major three tasks are:

-

Tissue drainage for fluid balance and waste disposal

-

Immune surveillance, including hosting and trafficking of immune cells

-

Uptake of dietary long-chain fatty acids and other highly lipophilic compounds in the intestine

Considerable effort has been devoted to the mechanisms and effects of ligand-receptor interaction and downstream signaling of the VEGFs [13] because these events are primary targets for pharmacological intervention. Less is known about the processes upstream of receptor binding such as proteolytic processing and secretion. However, such events create functional variety and regulate VEGF function, and e.g. proteases that release or activate VEGFs can therefore be regarded as signaling molecules [16].

2. VEGF-A, PlGF and VEGF-B

VEGF-A was the first member of the VEGF growth factor family to be discovered, and therefore it is often referred to in older publications simply as VEGF. The existence of a factor that can stimulate blood vessel growth had been postulated already in the middle of the last century by Michaelson based on the physiological and pathological vascularization of the eye [17]. In 1971, Judah Folkman predicted that the inhibition of this hypothetical angiogenesis factor could be used to prevent the growth of all solid tumors [18]. Fifteen years later, the team of Harold Dvorak isolated this factor [19]. They named it vascular permeability factor (VPF) based on its ability to increase the leakage of high molecular weight substances from the blood into the interstitial space. VPF appeared to be identical to VEGF, which had been isolated and cloned by the Ferrara group at Genentech [20]. Ferrara’s group was also persistent enough to continue to develop a mouse monoclonal antibody against VEGF-A into what is known nowadays as bevacizumab (Avastin®). In 2004, bevacizumab became the first antiangiogenic cancer drug approved by the FDA [21]. However, the possibilities of bevacizumab remained far beyond the originally anticipated role as a universal drug against solid tumors. It nevertheless established itself as the primary antiangiogenic target and standard of care in several diseases, including specific cancer types [22] and diabetic retinopathy [23].

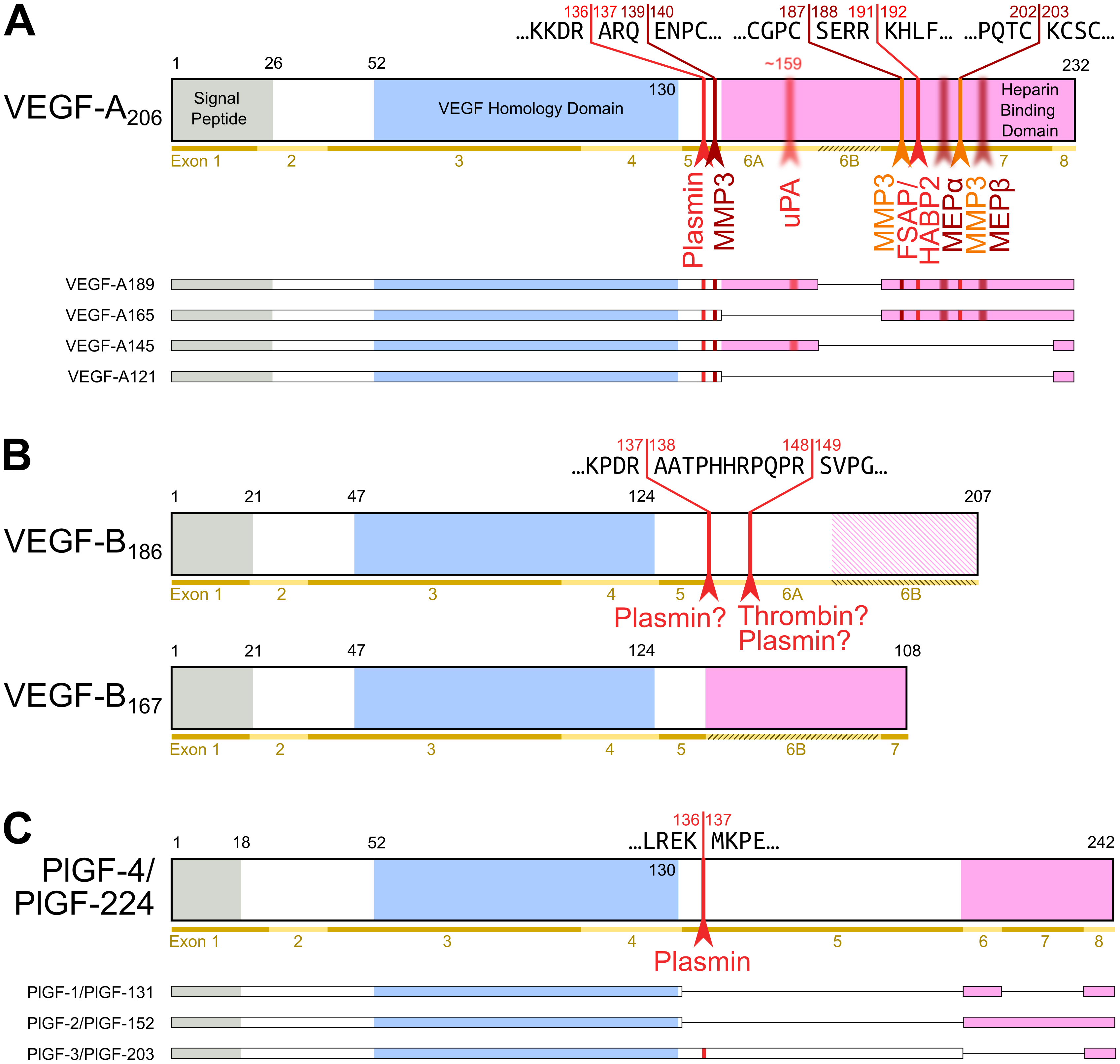

Figure 2. Most diversity among the hemangiogenic VEGFs is achieved by alternative splicing. Nevertheless, proteolytic processing of VEGF-A (A) [24] and placenta growth factor (PlGF) [25] (C) can convert the longer, heparin-binding isoforms into more soluble shorter species. (B) VEGF-B is a special case. Alternative splicing results in two isoforms that translate the same nucleotide sequence in two different frames resulting in a heparin-binding and a soluble isoform [26][27]. Due to the near-perfect cleavage context, thrombin has been suspected to be the responsible protease for VEGF-B186 cleavage [28]. Prothrombin is indeed expressed by 293T cells, in which the cleavage has been demonstrated [26]. Plasmin cleaves VEGF-B186 at at least four different sites, of which the two most likely predicted sites are indicated. Importantly, the predicted plasmin cleavage between Arg137 and Ala138 removes the interaction epitope for neuropilin-1 binding [26]. Semi-transparent, blurry arrows indicate cleavages, for which only the approximate position is known. The figure shows only the most sensitive site from the plasmin cleavages of VEGF-A since prolonged incubation results in progressing degradation [29]. VEGF-B186 appears to be progressively degraded by plasmin as well [26]. For VEGF-A and PlGF, the numbering is according to the longest shown isoform. VEGF-A is cleaved not only by MMP3 but also in a similar fashion by MMP7, MMP9, MMP19, and - less efficiently - by MMP1 and MMP16 [29].

Apart from VEGF-A, the hemangiogenic VEGF subgroup comprises PlGF (Placenta Growth Factor), which was named after the tissue from which its cDNA was isolated [30]. Similar to VEGF-B, it binds only to VEGF receptor-1. In-line with the observation that VEGFR-1 exerts a negative effect on angiogenesis, these growth factors have only a limited direct proliferative effect on vascular endothelial cells, and at least PlGF seems also not to be a major driver of tumor neovascularization [31]. Pinpointing the exact functions of PlGF and VEGF-B has been challenging but compared to VEGF-A, they likely play more restricted, specialized roles, e.g., in the angiogenesis of the cardiac muscle [32][33]. A uniting feature of VEGF-A, PlGF, and VEGF-B is the complex mRNA splicing, which increases protein diversity [24]. The major difference between the splice isoforms is their differential affinity to heparin (see Figure 2). This affinity allows for the interaction with extracellular matrix (ECM) and heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs). This interaction establishes growth factor gradients, which play important roles in vascular growth and network expansion [34]. VEGFB is additionally one of the few mammalian genes that features overlapping reading frames, which results in two different amino acid sequences being generated from the same nucleotide sequence [27].

3. The Lymphangiogenic Growth Factors VEGF-C and VEGF-D

VEGF-C is essential for the establishment of the lymphatic system during embryogenesis [35], while — at least in mammals — VEGF-D appears largely dispensible [36]. Consequently, mutations in the genes of the VEGF-C/VEGFR-3 signalling axis can give rise to hereditary lymphedema, and several such genes have been identified [37].

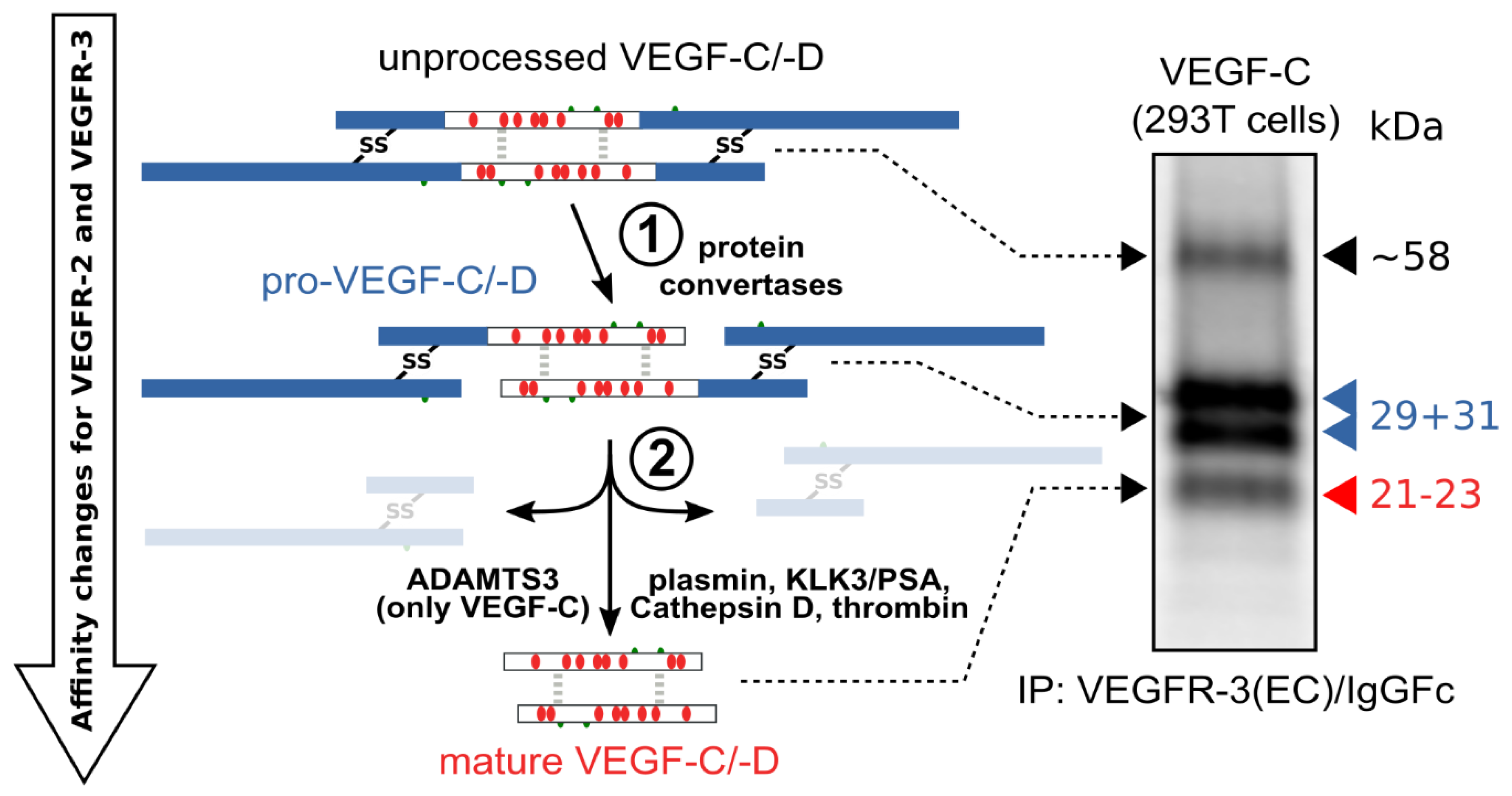

The hemangiogenic VEGFs are rendered inactive either through ECM-association or—as in the case for VEGF-A189—by their C-terminal auxiliary domain. Preventing receptor activation using inhibitory domains is also characteristic of the lymphangiogenic VEGFs. Upon secretion, VEGF-C and VEGF-D are kept inactive by their N- and C-terminal propeptides. Hence, the secreted forms are referred to as pro-VEGF-C and pro-VEGF-D. The removal of the propeptides requires two concerted proteolytic cleavages and happens in a very similar fashion for both VEGF-C and VEGF-D (see Figure 3):

Figure 3. Two proteolytic cleavages are needed to activate VEGF-C and VEGF-D. The first cleavage, by protein convertases, is constitutive and intracellular. The second is highly regulated and happens after secretion of the pro-forms. Many different enzymes have been shown to catalyze the second cleavage, but the primary activating protease of VEGF-C in mammalian developmental lymphangiogenesis is A Disintegrin and Metalloprotease With Thrombospondin Motifs-3 (ADAMTS3). The immunoprecipitation (IP) of transfected 293T cells with a VEGFR-3(EC)/IgGFc fusion protein pulls down the 58 kDa full-length VEGF-C, the pro-VEGF-C peptides of 31 kDa and 29 kDa, and the mature VEGF-C. Proteins were resolved under reducing conditions by SDS-PAGE.

-

Protein convertases constitutively cleave VEGF-C before secretion. This intracellular cleavage occurs between the central VEGF homology domain (VHD) and the C-terminal propeptide. However, it does not remove the C-terminal propeptide because it remains covalently attached to the rest of the molecule by disulfide bonds [38][39][40].

-

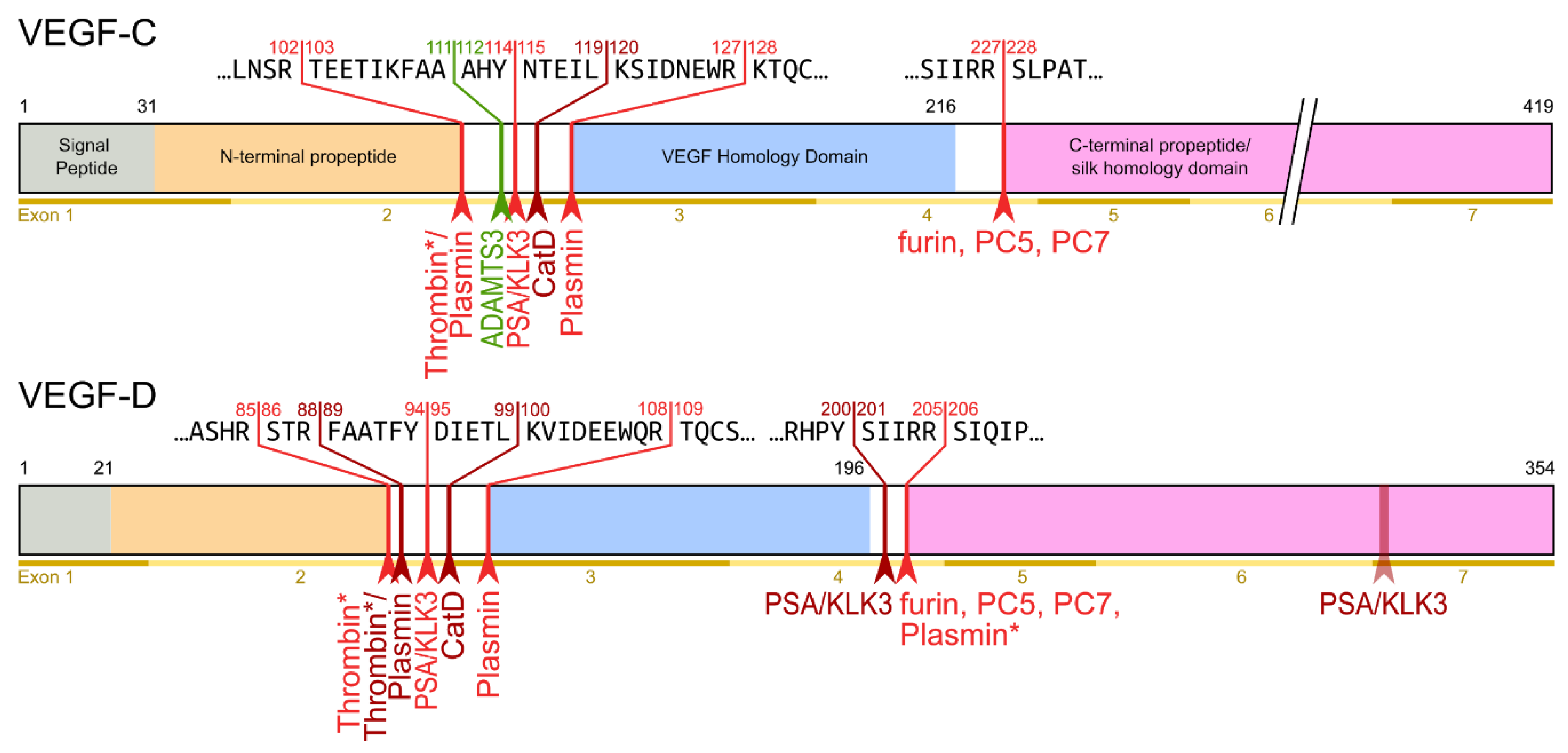

The second, extracellular cleavage activates the protein. This cleavage occurs between the N-terminal propeptide and the VHD [38] and can be mediated by different proteases. ADAMTS3 mediates VEGF-C activation in the embryonic development of the mammalian lymphatic system [41][42][43]. ADAMTS3 is specific for VEGF-C and does not activate VEGF-D. All other activating proteases target both VEGF-C and VEGF-D: plasmin [43][44], prostate-specific antigen (KLK3/PSA), cathepsin D (CatD) [45], and thrombin [46]. The resulting forms of VEGF-C and VEGF-D are referred to as active, mature, or short forms. However, they differ from each other at their N-termini because different proteases cleave at different positions within the linker between the N-terminal propeptide and the VHD (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Human VEGF-C and -D are processed in a very similar fashion. The major difference between VEGF-C and -D is that ADAMTS3 activates VEGF-C, but not VEGF-D. This is one of the reasons why ADAMTS3 and VEGF-C are essential for lymphatic development and embryonic survival [42], whereas VEGF-D deletion in mice is well tolerated [47]. While the figure shows the exon structure of VEGF-C and -D, mRNA splice isoforms have only been reported for murine Vegfc [48]. The detected splice variants do not contain the full VEGF homology domain and are therefore not shown here. *Cleavage site is only predicted based on the amino acid context.

Interestingly, pro-VEGF-C can competitively block the receptor activation of active, mature VEGF-C. Its propeptides allow VEGF receptor binding but interfere with receptor activation. Apart from VEGFR-3, pro-VEGF-C also binds the co-receptor neuropilin-2. C-terminal propeptide processing exposes two terminal arginines (R226,227), which contribute to the conserved binding site for neuropilins [49]. Because it is not entirely clear whether pro-VEGF-C is completely incapable of receptor activation or whether it has some residual activity, pro-VEGF-C is either a partial agonist or an antagonist of mature VEGF-C [43].

4. Outlook: Molecular Nudging

With the first successes in Crispr-Cas clinical trials, manipulating the VEGF/VEGFR signaling pathway at the genetic level appears theoretically possible. However, even cutting-edge trials limit themselves at the moment to cells that can be easily modified ex vivo (blood diseases such as sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia) [50] or to very localized targets [51]. We are still far from a systemic repair of solid tissues, which would be needed since blood and lymphatic vessels penetrate almost all our bodies’ organs. Several clinical trials to stimulate local blood vessel growth to ameliorate cardiovascular diseases did not yield any clinically useful results yet, but due to the large beneficial impact of even moderate improvements, research is still ongoing [52]. Since at least a fraction of the VEGF-C appears to originate from blood vascular endothelial cells, a vascular-targeted repair of lymphedema appears possible [53]. If sufficiently specific, the systemic delivery of regulatory factors such as CCBE1 or ADAMTS3 might alternatively result in a widespread low-level activation (“molecular nudging”) of endogenous VEGFR-3 signaling and a therapeutic effect. While such interventions do not reverse developmental routes already taken, they still might significantly improve life quality.

However, some forms of "molecular nudging" that affect the entire cardiovascular system have been described more than 40 years ago: High-altitude hypoxia appears to be cardioprotective in both men and animal models [54][55]. However, the mechanisms underlying the protection are still unclear due to a multitude of concurrent physiological changes associated with high altitude exposure, which result in uncertainty about which changes being actually causative [56]. In addition, similar benefits might be achieved by different adaptive strategies based on genetic variation [57][58]. Absent high altitude hypoxia, aerobic exercise is perhaps the easiest way to achieve a similar effect [59].

For cancer, being the prototype of a moving drug target, molecular nudging is not likely to have any impact. While a multitargeted anti-VEGF-A/-C/-D therapy might result in improved survival, any progress in this area will likely be incremental since using alternative tumor angiogenesis factors is only one of many escape mechanisms that tumors can deploy [60].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biology10020167

References

- de Groof, A.; Guelen, L.; Deijs, M.; van der Wal, Y.; Miyata, M.; Ng, K.S.; van Grinsven, L.; Simmelink, B.; Biermann, Y.; Grisez, L.; et al. A Novel Virus Causes Scale Drop Disease in Lates Calcarifer. PLOS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005074, doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005074.

- Lyttle, D.J.; Fraser, K.M.; Fleming, S.B.; Mercer, A.A.; Robinson, A.J. Homologs of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Are Encoded by the Poxvirus Orf Virus. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 84–92, doi:10.1128/JVI.68.1.84-92.1994.

- Meyer, M.; Clauss, M.; Lepple-Wienhues, A.; Waltenberger, J.; Augustin, H.G.; Ziche, M.; Lanz, C.; Büttner, M.; Rziha, H.-J.; Dehio, C. A Novel Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Encoded by Orf Virus, VEGF-E, Mediates Angiogenesis via Signalling through VEGFR-2 (KDR) but Not VEGFR-1 (Flt-1) Receptor Tyrosine Kinases. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 363–374, doi:10.1093/emboj/18.2.363.

- Ogawa, S.; Oku, A.; Sawano, A.; Yamaguchi, S.; Yazaki, Y.; Shibuya, M. A Novel Type of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, VEGF-E (NZ-7 VEGF), Preferentially Utilizes KDR/Flk-1 Receptor and Carries a Potent Mitotic Activity without Heparin-Binding Domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 31273–31282, doi:10.1074/jbc.273.47.31273.

- Yamazaki, Y.; Matsunaga, Y.; Tokunaga, Y.; Obayashi, S.; Saito, M.; Morita, T. Snake Venom Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors (VEGF-Fs) Exclusively Vary Their Structures and Functions among Species. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 9885–9891, doi:10.1074/jbc.M809071200.

- Tapio I. Heino; Terhi Kärpänen; Gudrun Wahlström; Marianne Pulkkinen; Ulf Eriksson; Kari Alitalo; Christophe Roos; The Drosophila VEGF receptor homolog is expressed in hemocytes. Mechanisms of Development 2001, 109, 69-77, 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00510-x.

- Marina Tarsitano; Sandro De Falco; Vincenza Colonna; James D. McGhee; M. Graziella Persico; The C. elegans pvf‐1 gene encodes a PDGF/VEGF‐like factor able to bind mammalian VEGF receptors and to induce angiogenesis. The FASEB Journal 2005, 20, 227-233, 10.1096/fj.05-4147com.

- Wiesmann, C.; Fuh, G.; Christinger, H.W.; Eigenbrot, C.; Wells, J.A.; de Vos, A.M. Crystal Structure at 1.7 Å Resolution of VEGF in Complex with Domain 2 of the Flt-1 Receptor. Cell 1997, 91, 695–704, doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80456-0.

- Fuh, G.; Li, B.; Crowley, C.; Cunningham, B.; Wells, J.A. Requirements for Binding and Signaling of the Kinase Domain Receptor for Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 11197–11204, doi:10.1074/jbc.273.18.11197.

- Leppänen, V.-M.; Prota, A.E.; Jeltsch, M.; Anisimov, A.; Kalkkinen, N.; Strandin, T.; Lankinen, H.; Goldman, A.; Ballmer-Hofer, K.; Alitalo, K. Structural Determinants of Growth Factor Binding and Specificity by VEGF Receptor 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 2425–2430, doi:10.1073/pnas.0914318107.

- Leppänen, V.-M.; Tvorogov, D.; Kisko, K.; Prota, A.E.; Jeltsch, M.; Anisimov, A.; Markovic-Mueller, S.; Stuttfeld, E.; Goldie, K.N.; Ballmer-Hofer, K.; et al. Structural and Mechanistic Insights into VEGF Receptor 3 Ligand Binding and Activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 12960–12965, doi:10.1073/pnas.1301415110.

- Apte, R.S.; Chen, D.S.; Ferrara, N. VEGF in Signaling and Disease: Beyond Discovery and Development. Cell 2019, 176, 1248–1264, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.021.

- Simons, M.; Gordon, E.; Claesson-Welsh, L. Mechanisms and Regulation of Endothelial VEGF Receptor Signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 611–625, doi:10.1038/nrm.2016.87.

- Carmeliet, P.; Ferreira, V.; Breier, G.; Pollefeyt, S.; Kieckens, L.; Gertsenstein, M.; Fahrig, M.; Vandenhoeck, A.; Harpal, K.; Eberhardt, C.; et al. Abnormal Blood Vessel Development and Lethality in Embryos Lacking a Single VEGF Allele. Nature 1996, 380, 435–439, doi:10.1038/380435a0.

- Ferrara, N.; Carver-Moore, K.; Chen, H.; Dowd, M.; Lu, L.; O’Shea, K.S.; Powell-Braxton, L.; Hillan, K.J.; Moore, M.W. Heterozygous Embryonic Lethality Induced by Targeted Inactivation of the VEGF Gene. Nature 1996, 380, 439–442, doi:10.1038/380439a0.

- Turk, B.; Turk, D.; Turk, V. Protease Signalling: The Cutting Edge. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 1630–1643, doi:10.1038/emboj.2012.42.

- Michaelson, I.C. The Mode of Development of the Vascular System of the Retina with Some Observations on Its Significance for Certain Retinal Disorders. Trans. Ophthalmol. Soc. UK 1948, 68, 137–180.

- Folkman, J. Tumor Angiogenesis: Therapeutic Implications. N. Engl. J. Med. 1971, 285, 1182–1186, doi:10.1056/NEJM197111182852108.

- Senger, D.R.; Galli, S.J.; Dvorak, A.M.; Perruzzi, C.A.; Harvey, V.S.; Dvorak, H.F. Tumor Cells Secrete a Vascular Permeability Factor That Promotes Accumulation of Ascites Fluid. Science 1983, 219, 983–985, doi:10.1126/science.6823562.

- Ferrara, N.; Leung, D.W.; Cachianes, G.; Winer, J.; Henzel, W.J. Purification and cloning of vascular endothelial growth factor secreted by pituitary folliculostellate cells. In Methods in Enzymology; David Barnes, J.P.M., Gordon H. Sato, Ed.; Peptide Growth Factors Part C; Academic Press, 1991; Vol. Volume 198, pp. 391–405, doi:10.1016/0076-6879(91)98040-d.

- Ferrara, N.; Hillan, K.J.; Novotny, W. Bevacizumab (Avastin), a Humanized Anti-VEGF Monoclonal Antibody for Cancer Therapy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 333, 328–335, doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.132.

- Garcia, J.; Hurwitz, H.I.; Sandler, A.B.; Miles, D.; Coleman, R.L.; Deurloo, R.; Chinot, O.L. Bevacizumab (Avastin®) in Cancer Treatment: A Review of 15 Years of Clinical Experience and Future Outlook. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2020, 86, 102017, doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102017.

- Guicciardo, E.; Lehti, T.A.; Korhonen, A.; Salvén, P.; Lehti, K.; Jeltsch, M.; Loukovaara, S. Lymphatics and the eye. [Finnish]. Duodecim 2020, 136, 1777–88, doi:10.5281/zenodo.4005517.

- Vempati, P.; Popel, A.S.; Mac Gabhann, F. Extracellular Regulation of VEGF: Isoforms, Proteolysis, and Vascular Patterning. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014, 25, 1–19, doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.11.002.

- Hoffmann, D.C.; Willenborg, S.; Koch, M.; Zwolanek, D.; Müller, S.; Becker, A.-K.A.; Metzger, S.; Ehrbar, M.; Kurschat, P.; Hellmich, M.; et al. Proteolytic Processing Regulates Placental Growth Factor Activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 17976-17989, jbc.M113.451831.

- Makinen, T.; Olofsson, B.; Karpanen, T.; Hellman, U.; Soker, S.; Klagsbrun, M.; Eriksson, U.; Alitalo, K.; Differential Binding of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor B Splice and Proteolytic Isoforms to Neuropilin-1. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 21217-21222, 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21217.

- Olofsson, B.; Pajusola, K.; von Euler, G.; Chilov, D.; Alitalo, K.; Eriksson, U. Genomic Organization of the Mouse and Human Genes for Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor B (VEGF-B) and Characterization of a Second Splice Isoform. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 19310–19317, doi:10.1074/jbc.271.32.19310.

- Yamazaki, Y.; Morita, T.; Molecular and Functional Diversity of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors. Mol. Divers. 2006, 10, 515-527, 10.1007/s11030-006-9027-3.

- Lee, S.; Jilani, S.M.; Nikolova, G.V.; Carpizo, D.; Iruela-Arispe, M.L.; Processing of VEGF-A by Matrix Metalloproteinases Regulates Bioavailability and Vascular Patterning in Tumors. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 169, 681-691, 10.1083/jcb.200409115.

- Maglione, D.; Guerriero, V.; Viglietto, G.; Delli-Bovi, P.; Persico, M.G. Isolation of a Human Placenta CDNA Coding for a Protein Related to the Vascular Permeability Factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 9267–9271, doi:10.1073/pnas.88.20.9267.

- Bais, C.; Wu, X.; Yao, J.; Yang, S.; Crawford, Y.; McCutcheon, K.; Tan, C.; Kolumam, G.; Vernes, J.-M.; Eastham-Anderson, J.; et al. PlGF Blockade Does Not Inhibit Angiogenesis during Primary Tumor Growth. Cell 2010, 141, 166–177, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.033.

- Luttun, A.; Tjwa, M.; Moons, L.; Wu, Y.; Angelillo-Scherrer, A.; Liao, F.; Nagy, J.A.; Hooper, A.; Priller, J.; De Klerck, B.; et al. Revascularization of Ischemic Tissues by PlGF Treatment, and Inhibition of Tumor Angiogenesis, Arthritis and Atherosclerosis by Anti-Flt1. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 831–840, doi:10.1038/nm731.

- Li, X.; Tjwa, M.; Van Hove, I.; Enholm, B.; Neven, E.; Paavonen, K.; Jeltsch, M.; Juan, T.D.; Sievers, R.E.; Chorianopoulos, E.; et al. Reevaluation of the Role of VEGF-B Suggests a Restricted Role in the Revascularization of the Ischemic Myocardium. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 1614–1620, doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.158725.

- Gerhardt, H.; Golding, M.; Fruttiger, M.; Ruhrberg, C.; Lundkvist, A.; Abramsson, A.; Jeltsch, M.; Mitchell, C.; Alitalo, K.; Shima, D.; et al. VEGF Guides Angiogenic Sprouting Utilizing Endothelial Tip Cell Filopodia. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 161, 1163–1177, doi:10.1083/jcb.200302047.

- Kärkkäinen, M.J.; Haiko P.; Sainio, K.; Partanen, J.; Taipale, J.; Petrova, T.V.; Jeltsch, M.; Jackson, D.G.; Talikka, M.; Rauvala, H.; et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor C is required for sprouting of the first lymphatic vessels from embryonic veins. Nat. Immunol. 2004, 5, 74-80, 10.1038/ni1013.

- Baldwin, M.; Halford, M.M.; Roufail, S.; Williams, R.A.; Hibbs, M.L.; Grail, D.; Kubo, H.; Stacker, S.A.; Achen, M.G.; Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor D Is Dispensable for Development of the Lymphatic System. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 2441-2449, 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2441-2449.2005.

- Brouillard, P.; Boon, L.; Vikkula, M.; Genetics of lymphatic anomalies. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 124, 898-904, 10.1172/JCI71614.

- Joukov, V.; Sorsa, T.; Kumar, V.; Jeltsch, M.; Claesson-Welsh, L.; Cao, Y.; Saksela, O.; Kalkkinen, N.; Alitalo, K. Proteolytic Processing Regulates Receptor Specificity and Activity of VEGF-C. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 3898–3911, doi:10.1093/emboj/16.13.3898.

- McColl, B.K.; Paavonen, K.; Karnezis, T.; Harris, N.C.; Davydova, N.; Rothacker, J.; Nice, E.C.; Harder, K.W.; Roufail, S.; Hibbs, M.L.; et al. Proprotein Convertases Promote Processing of VEGF-D, a Critical Step for Binding the Angiogenic Receptor VEGFR-2. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 1088–1098, doi:10.1096/fj.06-7060com.

- Siegfried, G.; Basak, A.; Cromlish, J.A.; Benjannet, S.; Marcinkiewicz, J.; Chrétien, M.; Seidah, N.G.; Khatib, A.-M. The Secretory Proprotein Convertases Furin, PC5, and PC7 Activate VEGF-C to Induce Tumorigenesis. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1723–1732, doi:10.1172/JCI17220.

- Bui, H.M.; Enis, D.; Robciuc, M.R.; Nurmi, H.J.; Cohen, J.; Chen, M.; Yang, Y.; Dhillon, V.; Johnson, K.; Zhang, H.; et al. Proteolytic Activation Defines Distinct Lymphangiogenic Mechanisms for VEGFC and VEGFD. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 2167–2180, 10.1172/JCI83967.

- Janssen, L.; Dupont, L.; Bekhouche, M.; Noel, A.; Leduc, C.; Voz, M.; Peers, B.; Cataldo, D.; Apte, S.S.; Dubail, J.; et al. ADAMTS3 Activity Is Mandatory for Embryonic Lymphangiogenesis and Regulates Placental Angiogenesis. Angiogenesis 2015, 1–13, doi:10.1007/s10456-015-9488-z.

- Jeltsch, M.; Jha, S.K.; Tvorogov, D.; Anisimov, A.; Leppänen, V.-M.; Holopainen, T.; Kivelä, R.; Ortega, S.; Kärpanen, T.; Alitalo, K. CCBE1 Enhances Lymphangiogenesis via A Disintegrin and Metalloprotease With Thrombospondin Motifs-3–Mediated Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-C Activation. Circulation 2014, 129, 1962–1971, doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002779.

- McColl, B.K.; Baldwin, M.E.; Roufail, S.; Freeman, C.; Moritz, R.L.; Simpson, R.J.; Alitalo, K.; Stacker, S.A.; Achen, M.G. Plasmin Activates the Lymphangiogenic Growth Factors VEGF-C and VEGF-D. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 863–868, doi:10.1084/jem.20030361.

- Jha, S.K.; Rauniyar, K.; Chronowska, E.; Mattonet, K.; Maina, E.W.; Koistinen, H.; Stenman, U.-H.; Alitalo, K.; Jeltsch, M. KLK3/PSA and Cathepsin D Activate VEGF-C and VEGF-D. eLife 2019, 8, e44478, doi:10.7554/eLife.44478.

- Lim, L.; Bui, H.; Farrelly, O.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Enis, D.; Ma, W.; Chen, M.; Oliver, G.; Welsh, J.D.; et al. Hemostasis Stimulates Lymphangiogenesis through Release and Activation of VEGFC. Blood 2019, 134, 1764–1775, doi:10.1182/blood.2019001736.

- Baldwin, M.E.; Halford, M.M.; Roufail, S.; Williams, R.A.; Hibbs, M.L.; Grail, D.; Kubo, H.; Stacker, S.A.; Achen, M.G. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor D Is Dispensable for Development of the Lymphatic System. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 2441–2449, doi:10.1128/MCB.25.6.2441-2449.2005.

- Lee, J.; Gray, A.; Yuan, J.; Luoh, S.M.; Avraham, H.; Wood, W.I. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-Related Protein: A Ligand and Specific Activator of the Tyrosine Kinase Receptor Flt4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 1988–1992, doi:10.1073/pnas.93.5.1988.

- Kärpänen, T.; Heckman, C.A.; Keskitalo, S.; Jeltsch, M.; Ollila, H.; Neufeld, G.; Tamagnone, L.; Alitalo, K. Functional Interaction of VEGF-C and VEGF-D with Neuropilin Receptors. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 1462–1472, doi:10.1096/fj.05-5646com.

- Frangoul, H.; Altshuler, D.; Cappellini, M.D.; Chen, Y.-S.; Domm, J.; Eustace, B.K.; Foell, J.; de la Fuente, J.; Grupp, S.; Handgretinger, R.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing for Sickle Cell Disease and β-Thalassemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2031054.

- Ledford, H. CRISPR Treatment Inserted Directly into the Body for First Time. Nature 2020, 579, 185, doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00655-8.

- Ylä-Herttuala, S.; Bridges, C.; Katz, M.G.; Korpisalo, P.; Angiogenic gene therapy in cardiovascular diseases: dream or vision?. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 1365-1371, 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw547.

- Kiseleva, R.Y.; Glassman, P.M.; Greineder, C.F.; Hood, E.D.; Shuvaev, V.V.; Muzykantov, V.R. Targeting Therapeutics to Endothelium: Are We There Yet? Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2018, 8, 883–902, doi:10.1007/s13346-017-0464-6.

- Mortimer, E.A.Jr.; Monson, R.R.; MacMahon, B.; Reduction in Mortality from Coronary Heart Disease in Men Residing at High Altitude. N. Engl. J. Med. 1977, 296, 581-585, 10.1056/NEJM197703172961101.

- Neckár, J; Szárszoi, O.; Koten, L.; Ost'ádal, B.; Grover, G.J.; Kolár, F.; Effects of mitochondrial K(ATP) modulators on cardioprotection induced by chronic high altitude hypoxia in rats. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002, 55, 567-575, 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00456-x.

- Ke, J.; Wang, L.; Xiao, D.. Cardiovascular Adaptation to High-Altitude Hypoxia (in: Hypoxia and Human Diseases); IntechOpen: London, 2017; pp. 117-134, doi:10.5772/65354.

- Stembridge, M.; Williams, A.M.; Gasho, C.; Dawkins, T.G.; Drane, A.; Villafuerte, F.C.; Levine, B.D.; Shave, R.; Ainslie, P.N.; The overlooked significance of plasma volume for successful adaptation to high altitude in Sherpa and Andean natives. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 16177-16179, 10.1073/pnas.1909002116.

- Lorenzo, F.R.; Huff, C.; Myllymäki, M.; Olenchock, B.; Swierczek, S.; Tashi, T.; Gordeuk, V.; Wuren, T.; Ri-Li, G.; McClain, D.A.; et al. A genetic mechanism for Tibetan high-altitude adaptation. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 951-956, 10.1038/ng.3067.

- Pinckard, K.; Baskin, K.K.; Stanford, K.I.; Effects of Exercise to Improve Cardiovascular Health. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 6, 69, 10.3389/fcvm.2019.00069.

- Bergers, G.; Hanahan, D. Modes of Resistance to Anti-Angiogenic Therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 592–603, doi:10.1038/nrc2442.