Brain Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) consist of feeder arteries that amalgamate and form a nidus, shunting the oxygenated blood directly into the venous system without an interposing capillary network.

- arteriovenous malformation

- de novo

- acquired

- seizure

- hemorrhage

1. Introduction

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) of the brain consist of feeder arteries that amalgamate and form a nidus, shunting the oxygenated blood directly into the venous system without an interposing capillary network [1][2][3][4]. The most common and undeniably the most severe clinical presentation is intracranial hemorrhage, AVMs representing an important source of mortality and morbidity, especially in the younger population. Epilepsy, progressive neurological deficit, and chronic headache are less frequently encountered in patients harboring this pathology. Asymptomatic patients may benefit from simple clinical and imagistic observation, whereas those with minimal symptoms can be managed conservatively. Currently, the most effective and permanent treatment method or ruptured or symptomatic AVMs consists of microsurgical resection of the nidus and rigorous hemostasis, but radiosurgery and endovascular embolization are also viable management options.

AVMs are traditionally considered congenital, an estimated 95% of these lesions being sporadic in nature, whereas the remaining 5% are familial and most often associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) [4]. The congenital aspect derives from the observation that these lesions may occur at any age, from infants and children to adults and elderly alike, even though there is a scarcity of conclusive data to demonstrate this fact [5][6][7].

Our current grasp of cerebral AVMs has dramatically improved over the last few decades, by delving into the genetic and epigenetic intricacies of their pathogenesis [8][9][10]. Data concerning the molecular underlying of AVMs come from AVM syndromes as well as from the analysis of sporadic cases of AVMs. For instance, genetic events involving members of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling, namely Endoglin (ENG) and Activin A receptor type I (ACVR1 or ALK1) are causative in HHT type 1 and type 2, respectively [11][12]. Mutations in SMAD4, which is a downstream effector of TGF-β, cause the combined syndrome of HHT with juvenile polyposis [13]. In agreement with such an interpretation, conditional knock out of either ENG or ALK1 resulted in arteriovenous malformations of the skin in mice only after a secondary injury, for example wounding [14][15]. Moreover, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has the ability to mimic this wounding effect on skin AVM development, at least in animal models [16]. In the case of the more common sporadically occurring AVMs, somatic KRAS mutations were discovered in approximately 55% of brain AVM specimens, also linked to lower patient age, and a larger nidus average size [17][18][19], whereas the non-coding polymorphism in ALK1 (ALK1 IVS3-35A>G) was established as a genetic risk factor in two independent studies [20][21]. Other polymorphisms linked to sporadic AVMs include polymorphisms in ENG [20], interleukin-1β (IL1B) [22], and VEGF [23]. Even so, we are currently unable to effectively validate whether these malformations actually develop during embryogenesis and evolve during one’s lifetime, or if they appear at a later point in time when certain microenvironmental conditions are met.

There is a mounting number of pertinent case reports detailing AVMs that occurred sporadically after credible evidence of their initial absence. Either adequate imaging studies or intraoperative examinations preceded the certain appearance of these vascular malformations, which were then discovered at a variable interval. A diversity of preexisting circumstances or pathologies either influenced or initiated the development of AVMs in already susceptible patients. Ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attacks (TIA) were among the most common ailments preceding de novo AVMs [24], as were seizures [25]. Certain individuals previously harbored another type of intracranial vascular pathology, or even a differently located AVM, highlighting the irrefutable predisposition for such an occurrence [26]. Intracranial tumors with a highly vascular component have also been described as potential triggers for previously absent AVMs [27]. An earlier hemorrhagic episode [28] and even head trauma of variable severity have also been reported as generators for de novo AVMs [29].

Notwithstanding the fact that cerebral AVMs are a rare pathology, they are cited as the most common cause of intracranial hemorrhage in children and young adults, leading to a lifelong threat of death or disability [2][3][4][30][31]. As such, elucidating their true natural history is crucial in order to establish the best possible course of diagnosis and management, and help lessen their socio-economic encumberment.

2. ‘De Novo’ Brain AVMs

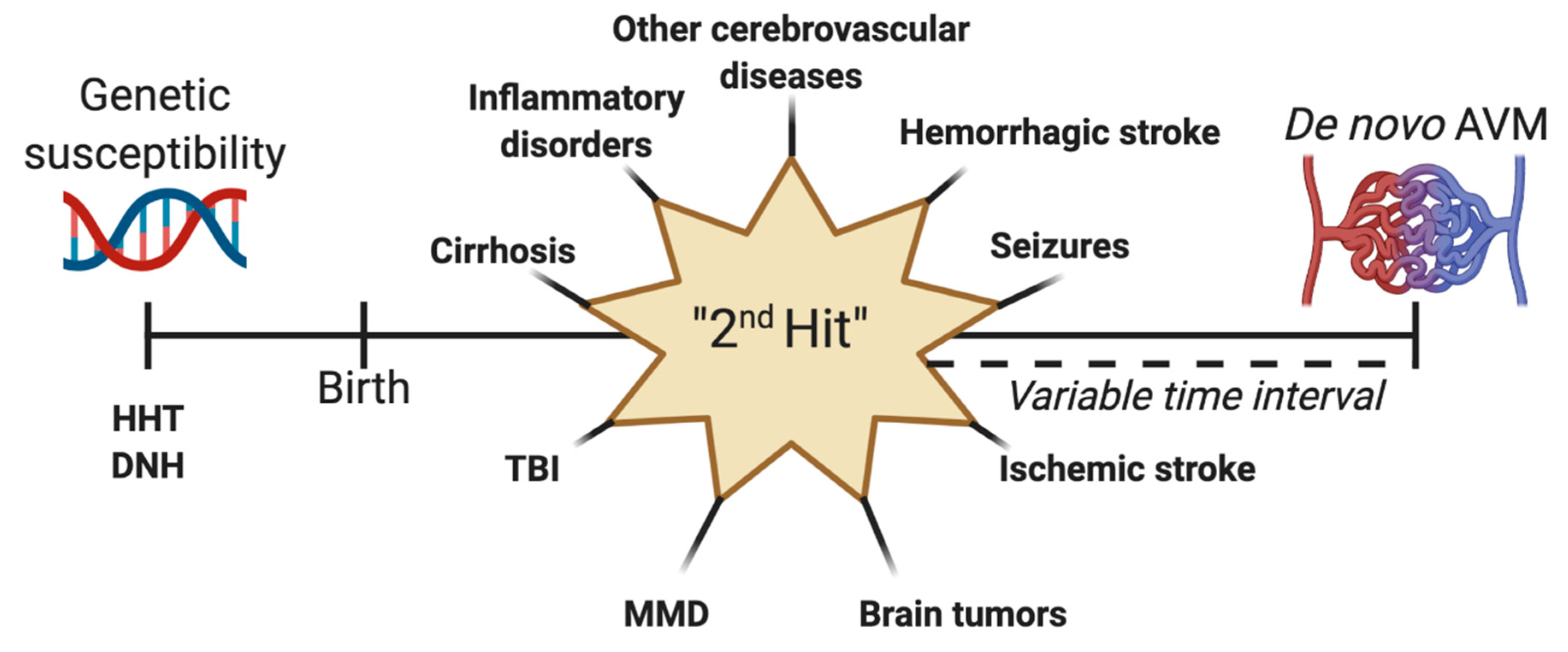

Increasing evidence suggests that at least some of the AVMs discovered develop some time after birth. We are still a long way from finally elucidating their true nature, though there is reason to believe that they can also appear after a proposed ‘second hit’ during a patient’s lifetime (Figure 5). The congenital or acquired characteristic of AVMs may have a tremendous impact on prognosis, risk of hemorrhage, and short and long-term management.

Figure 5. Schematization of the “second hit” theory for the development of de novo arteriovenous malformations (AVM). Genetic susceptibility can be represented by syndromes such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) or diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis (DNT). After birth, a second may occur, leading to the formation of an acquired AVM after a variable point in time. This second hit can be a preexisting vascular lesion or malformation, hemorrhagic stroke, seizures, ischemic stroke, brain tumors, Moyamoya disease (MMD), traumatic brain injury (TBI), cirrhosis, or inflammatory lesions.

Figure 5. Schematization of the “second hit” theory for the development of de novo arteriovenous malformations (AVM). Genetic susceptibility can be represented by syndromes such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) or diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis (DNT). After birth, a second may occur, leading to the formation of an acquired AVM after a variable point in time. This second hit can be a preexisting vascular lesion or malformation, hemorrhagic stroke, seizures, ischemic stroke, brain tumors, Moyamoya disease (MMD), traumatic brain injury (TBI), cirrhosis, or inflammatory lesions.

Despite being a rare pathology, AVMs represent the most frequent cause of intracranial hemorrhage in young patients. Furthermore, it is possible that the real number of ruptured de novo AVMs is underrepresented since such lesions presenting with acute hemorrhage in patients that have never undergone a previous CT or MRI scan are automatically labeled as congenital in nature.

It must be noted that all of the diagnoses of de novo AVMs were made in conjunction with a previous associated pathology or injury. Had this not been the case, imaging studies prior to the symptomatic manifestation of the acquired AVMs would have been unnecessary, and the initial absence of these vascular lesions could not have been documented. Patients who experience seizures with or without apparent underlying causes, hemorrhagic or ischemic strokes, TBI of varying severity, other cerebrovascular malformations, or highly vascular tumors should receive regular imaging screening which includes DSA more often to highlight or exclude the formation of de novo AVMs. Further research should be conducted to more adequately ascertain the congenital or acquired characteristic of brain AVMs.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/medicina57030201

References

- Florian, I.A.; Stan, H.M.; Florian, I.; Cheptea, M.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. Prognostic Factors in the Neurosurgical Treatment of Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformations. In World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies Symposia 2018 Proceeding Book; Kandasamy, R., Ed.; Editografica: Bolognia, Italy, 2019; pp. 232–241.

- Florian, I.S.; Baritchii, A.; Trifoi, S. Arterio-venous Mallformations. In Tratat de Chirurgie, 2nd ed.; Popescu, I., Ciuce, C., Eds.; Editura Academiei Romane: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2014; Volume 6, pp. 402–410.

- Florian, I.S.; Perju-Dumbravă, L. (Eds.) Therapeutic Options in Hemorrhagic Strokes; Editura Medicală Universitară, Iuliu Hațieganu: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2007; pp. 331–346.

- Kalb, S.; Gross, B.A.; Nakaji, P. 20-Vascular Malformations (Arteriovenous Malformations and Dural Arteriovenous Fistulas). In Principles of Neurological Surgery, 4th ed.; Content Repository Only: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018.

- Dalton, A.; Dobson, G.; Prasad, M.; Mukerji, N. De novo intracerebral arteriovenous malformations and a review of the theories of their formation. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 32, 305–311.

- Morales-Valero, S.F.; Bortolotti, C.; Sturiale, C.; Lanzino, G. Are parenchymal AVMs congenital lesions? Neurosurg. Focus 2014, 37, E2.

- Tasiou, A.; Tzerefos, C.; Alleyne, C.H., Jr.; Boccardi, E.; Karlsson, B.; Kitchen, N.; Spetzler, R.F.; Tolias, C.M.; Fountas, K.N. Arteriovenous Malformations: Congenital or Acquired Lesions? World Neurosurg. 2020, 134, e799–e807.

- Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Shi, Y.; Huang, G.; Chen, L.; Tan, H.; Wang, Z.; Yin, C.; Hu, J. Deep Sequencing of Small RNAs in Blood of Patients with Brain Arteriovenous Malformations. World Neurosurg. 2018, 115, e570–e579.

- Huang, J.; Song, J.; Qu, M.; Wang, Y.; An, Q.; Song, Y.; Yan, W.; Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; et al. MicroRNA-137 and microRNA-195* inhibit vasculogenesis in brain arteriovenous malformations. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 82, 371–384.

- Weinsheimer, S.; Bendjilali, N.; Nelson, J.; Guo, D.E.; Zaroff, J.G.; Sidney, S.; Mcculloch, C.E.; Al-Shahi Salman, R.; Berg, J.N.; Koeleman, B.P.; et al. Genome-wide association study of sporadic brain arteriovenous malformations. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2016, 87, 916–923.

- Johnson, D.W.; Berg, J.N.; Baldwin, M.A.; Gallione, C.J.; Marondel, I.; Yoon, S.J.; Stenzel, T.T.; Speer, M.; Pericak-Vance, M.A.; Diamond, A.; et al. Mutations in the activin receptor-like kinase 1 gene in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 2. Nat. Genet. 1996, 13, 189–195.

- Mcallister, K.A.; Grogg, K.M.; Johnson, D.W.; Gallione, C.J.; Baldwin, M.A.; Jackson, C.E.; Helmbold, E.A.; Markel, D.S.; Mckinnon, W.C.; Murrell, J.; et al. Endoglin, a TGF-beta binding protein of endothelial cells, is the gene for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Nat. Genet. 1994, 8, 345–351.

- Gallione, C.J.; Repetto, G.M.; Legius, E.; Rustgi, A.K.; Schelley, S.L.; Tejpar, S.; Mitchell, G.; Drouin, E.; Westermann, C.J.; Marchuk, D.A. A combined syndrome of juvenile polyposis and hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia associated with mutations in MADH4 (SMAD4). Lancet 2004, 363, 852–859.

- Garrido-Martin, E.M.; Nguyen, H.L.; Cunningham, T.A.; Choe, S.W.; Jiang, Z.; Arthur, H.M.; Lee, Y.J.; Oh, S.P. Common and distinctive pathogenetic features of arteriovenous malformations in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia 1 and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia 2 animal models--brief report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 2232–2236.

- Park, S.O.; Wankhede, M.; Lee, Y.J.; Choi, E.J.; Fliess, N.; Choe, S.W.; Oh, S.H.; Walter, G.; Raizada, M.K.; Sorg, B.S.; et al. Real-time imaging of de novo arteriovenous malformation in a mouse model of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 3487–3496.

- Han, C.; Choe, S.; Kim, Y.H.; Acharya, A.P.; Keselowsky, B.G.; Sorg, B.S.; Lee, Y.-J.; Oh, S.P. VEGF neutralization can prevent and normalize arteriovenous malformations in an animal model for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia 2. Angiogenesis 2014, 17, 823–830.

- Bameri, O.; Salarzaei, M.; Parooie, F. KRAS/BRAF mutations in brain arteriovenous malformations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2021.

- Goss, J.A.; Huang, A.Y.; Smith, E.; Konczyk, D.J.; Smits, P.J.; Sudduth, C.L.; Stapleton, C.; Patel, A.; Alexandrescu, S.; Warman, M.L.; et al. Somatic mutations in intracranial arteriovenous malformations. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226852.

- Priemer, D.S.; Vortmeyer, A.O.; Zhang, S.; Chang, H.Y.; Curless, K.L.; Cheng, L. Activating KRAS mutations in arteriovenous malformations of the brain: Frequency and clinicopathologic correlation. Hum. Pathol. 2019, 89, 33–39.

- Pawlikowska, L.; Tran, M.N.; Achrol, A.S.; Ha, C.; Burchard, E.; Choudhry, S.; Zaroff, J.; Lawton, M.T.; Castro, R.; Mcculloch, C.E.; et al. Polymorphisms in transforming growth factor-beta-related genes ALK1 and ENG are associated with sporadic brain arteriovenous malformations. Stroke 2005, 36, 2278–2280.

- Simon, M.; Franke, D.; Ludwig, M.; Aliashkevich, A.F.; Köster, G.; Oldenburg, J.; Boström, A.; Ziegler, A.; Schramm, J. Association of a polymorphism of the ACVRL1 gene with sporadic arteriovenous malformations of the central nervous system. J. Neurosurg. 2006, 104, 945–949.

- Kim, H.; Hysi, P.G.; Pawlikowska, L.; Poon, A.; Burchard, E.G.; Zaroff, J.G.; Sidney, S.; Ko, N.U.; Achrol, A.S.; Lawton, M.T.; et al. Common variants in interleukin-1-Beta gene are associated with intracranial hemorrhage and susceptibility to brain arteriovenous malformation. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2009, 27, 176–182.

- Chen, H.; Gu, Y.; Wu, W.; Chen, D.; Li, P.; Fan, W.; Lu, D.; Zhao, F.; Qiao, N.; Qiu, H.; et al. Polymorphisms of the vascular endothelial growth factor A gene and susceptibility to sporadic brain arteriovenous malformation in a Chinese population. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 18, 549–553.

- Pabaney, A.H.; Rammo, R.A.; Tahir, R.A.; Seyfried, D. Development of De Novo Arteriovenous Malformation Following Ischemic Stroke: Case Report and Review of Current Literature. World Neurosurg. 2016, 96, 608.e5–608.e12.

- Dogan, S.N.; Bagcilar, O.; Mammadov, T.; Kizilkilic, O.; Islak, C.; Kocer, N. De Novo Development of a Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformation: Case Report and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2019, 126, 257–260.

- Torres-Quinones, C.; Koch, M.J.; Raymond, S.B.; Patel, A. Left Thalamus Arteriovenous Malformation Secondary to Radiation Therapy of Original Vermian Arteriovenous Malformation: Case Report. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2019, 28, e53–e59.

- Lo Presti, A.; Rogers, J.M.; Assaad, N.N.A.; Rodriguez, M.L.; Stoodley, M.A.; Morgan, M.K. De novo brain arteriovenous malformation after tumor resection: Case report and literature review. Acta Neurochir. 2018, 160, 2191–2197.

- Rodrigues De Oliveira, L.F.; Castro-Afonso, L.H.; Freitas, R.K.; Colli, B.O.; Abud, D.G. De Novo Intracranial Arteriovenous Malformation-Case Report and Literature Review. World Neurosurg. 2020, 138, 349–351.

- Gonzalez, L.F.; Bristol, R.E.; Porter, R.W.; Spetzler, R.F. De novo presentation of an arteriovenous malformation. Case report and review of the literature. J. Neurosurg. 2005, 102, 726–729.

- Mohr, J.P.; Yaghi, S. Management of unbled brain arteriovenous malformation study. Neurol. Clin. 2015, 33, 347–359.

- Solomon, R.A.; Connolly, E.S., Jr. Arteriovenous Malformations of the Brain. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 498.