Radionuclide imaging of HER2 expression in tumours may enable stratification of patients with breast, ovarian, and gastroesophageal cancers for HER2-targeting therapies. A first-generation HER2-binding affibody molecule [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2 demonstrated favorable imaging properties in preclinical studies. Thereafter, the affibody scaffold has been extensively modified, which increased its melting point, improved storage stability, and increased hydrophilicity of the surface. In this study, a second-generation affibody molecule (designated ZHER2:41071) with a new improved scaffold has been prepared and characterized. HER2-binding, biodistribution, and tumour-targeting properties of [99mTc]Tc-labelled ZHER2:41071 were investigated. These properties were compared with properties of the first-generation affibody molecules, [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2 and [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:2395. [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071 bound specifically to HER2 expressing cells with an affinity of 58 ± 2 pM. The renal uptake for [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071 and [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2 was 25–30 fold lower when compared with [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:2395. The uptake in tumour and kidney for [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071 and [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2 in SKOV-3 xenografts was similar. In conclusion, an extensive re-engineering of the scaffold did not compromise imaging properties of the affibody molecule labelled with 99mTc using a GGGC chelator. The new probe, [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071 provided the best tumour-to-blood ratio compared to HER2-imaging probes for single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) described in the literature so far. [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071 is a promising candidate for further clinical translation studies.

- HER2

- radionuclide molecular imaging

- affibody molecule

- technetium-99m

- second-generation scaffold

1. Introduction

Human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2) is a transmembrane receptor belonging to the receptor tyrosine kinase superfamily. HER2 is overexpressed in a substantial fraction of breast, gastroesophageal, and ovarian cancers, and its elevated expression is associated with a poor prognosis [1][2][3]. HER2-overexpressing breast and gastroesophageal malignant tumors respond to treatment with HER2-targeting monoclonal antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors [3][4]. However, only tumors with high HER2 expression respond to specific targeting therapeutics. Therefore, the information concerning the HER2 expression level is critical for patients’ management [5]. The issue of current methodology for HER2 determination, analysis of biopsy material, and its invasiveness complicates multiple samplings. Thus, the problems of heterogeneous expression of HER2 [6] or an expression change in response to therapy [7] are difficult to solve within this methodology.

Radionuclide molecular imaging enables non-invasive detection of HER2 in both primary tumors and metastases without false-negative results originating from sampling errors. The first clinical studies proving this approach were performed with the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab labelled with a single photon emitter indium-111 [8][9]. Further progress in the use of antibody-based probes was achieved by the use of a long-lived positron emitter zirconium-89 and application of positron emission tomography (PET), which improved sensitivity and resolution [10]. Still, imaging probes based on therapeutic antibodies clear slowly from blood. This causes a low imaging contrast (even 4–5 days after injection) and an elevated dose burden [11]. The use of small imaging probes, which are based on the VHH domain or engineered scaffold proteins, enables to reduce the optimal imaging time to a few hours after injection and to increase the contrast of imaging, which enhances sensitivity [12]. One of the promising scaffold proteins for radionuclide imaging is the affibody molecule [12][13][14]. Affibody molecules are based on the 58-amino acid cysteine-free scaffold. They can be synthesized chemically or produced in bacteria by the use of recombinant DNA technology [13][14]. A small size, high thermal stability, site-specific radio-labelling, and high affinity are the features rendering affibody molecules excellent targeting agents [13][14]. The first generation affibody molecules have demonstrated an impressive capability to image HER2-expressing tumours in preclinical [15][16][17] and clinical [18] studies. Thereafter, the affibody scaffold was extensively re-engineered and 11 of 45 amino acids in the non-binding part were substituted [19] (Figure 1). The substitutions have improved the yield of peptide synthesis of affibody molecules and their stability. The residual binding to IgG and IgM was essentially eliminated to facilitate the blood clearance. The hydrophilicity of the water-exposed surface was appreciably enhanced by substitution of alanines by serines.

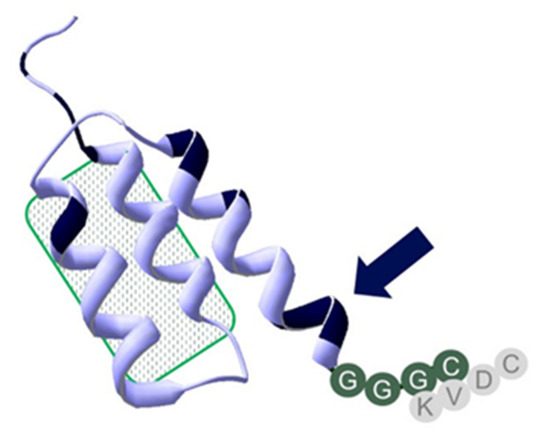

Figure 1. Overview of structural differences, features, and chelator positioning of ZHER2:41071, ZHER2:V2, and ZHER2:2395. All three constructs share the amino acid structure in the binding site, highlighted by the patch with a green pattern. Shared sequences are in a light blue structure, positions with scaffold variation are highlighted in black. The one close to the C-terminal chelator sequence GGGC (marked with an arrow) is consistent of an –SES- amino acids sequence, which replaced an -NDA-sequence to further improve peptide stability and increase hydrophilicity of the affibody molecule. The -SES- motif could have challenged efficient labeling by competing with the GGGC-chelator. Placement of a KVDC chelating sequence within ZHER2:2395 as compared to HER2:V2 and HER2:41071 is shown in gray.

PET studies using the DOTA-conjugated 68Ga-labelled second-generation affibody molecule ABY-025 have demonstrated excellent sensitivity and specificity in detecting HER2 expressing metastases in patients with breast cancer [20]. Importantly, a typical clinical investigation using this tracer would give an effective dose in the range of 5–6 mSv [21], which is appreciably lower compared with doses typical for immunoPET (14–22 mSv) [11]. Still, PET imaging is relatively available in Northern America and Western Europe. In South America, Asia, Africa, and even in some European countries, PET imaging is less accessible, while the use of SPECT is more common. SPECT imaging is possible using 111In-labelled ABY-025 [22], but this nuclide is expensive and requires medium energy collimators, which decrease resolution and sensitivity.

The use of technetium-99m (T1/2 = 6 h) would be much more attractive from a clinical point of view [23]. This nuclide is cheap and readily available because of its generator production. The decay scheme of 99mTc make this radionuclide almost ideal for radiopharmaceutical labelling because of its optimal half-life, benign dosimetry, and possibility to use low-energy high-resolution collimators, which increases the sensitivity of imaging. The labelling of first generation affibody molecules with 99mTc was well investigated. Particularly interesting was the labelling using peptide-based chelators. It was shown that composition of such chelators and their position in affibody molecules might substantially modify biodistribution of 99mTc-labeled affibody molecules and the excretion pathway [24]. A selection of an optimal amino acid sequence of mercaptoacetyl-containing chelators in N-terminus may reduce hepatobiliary excretion [25][26] and uptake in liver and kidneys [27]. More interesting was an application of cysteine-containing peptide-based chelators. It was shown that placement of a cysteine at the C-terminus of affibody molecules forms the N3S chelator (-KVDC), which provides stable coupling of 99mTc [16]. The 99mTc-labelled HER2-binding ZHER2:2395 (having a KVDC chelating sequence at the C-terminus) demonstrated an excellent targeting specificity and high imaging contrast of HER2 expression (tumor-to-blood ratio 121 ± 24, 4 h after injection) in a murine model [16]. In this case, the affibody molecule could be produced using both recombinant production and peptide synthesis [28]. An advantage of this approach is that an additional conjugation of a chelator is not required, which simplifies a manufacturing process and reduces production costs. The labelling procedure permits a formulation of freeze-dried kits [29], which facilitates a clinical translation. However, ZHER2:2395 had a high renal uptake (140–190 %ID/g, 4 h after injection) [16]. A strong influence of amino acids’ composition and their order on biodistribution and targeting properties has also been found for this type of chelator [17][30]. The best imaging contrast has been demonstrated by [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2 Affibody molecule containing a –GGGC chelating sequence. It has been shown that the [99mTc](Tc=O)–GGGC complex acts as a non-residualizing label. Activity, which was reabsorbed and rapidly internalized in the kidney, was rapidly excreted. In tumors, where internalization of affibody molecules is slow, the retention of activity was very good due to strong binding of affibody molecules to HER2 on cellular membranes [17]. This provided a combination of a good imaging construct with low renal uptake of [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2.

The –GGGC chelator is a potential candidate for labelling of the second generation of affibody molecules. However, rearranging amino acids of the scaffold might be associated with a risk of creating an additional chelating pocket by clustering amino acids with electron-donating side-chains. It has been suggested that such side-chains might participate in complexing of technetium [31]. This can result in a loss of labelling site-specificity and modification of stability of a conjugate and its pharmacokinetics. For example, introduction of the HEHEHE-tag at the N-terminus of ZHER2:V2 resulted in a noticeable change of biodistribution of the resulting construct, particularly much higher in renal uptake [32]. The binding site composition of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)--binding affibody molecule ZEGFR:2377 contains a chelating pocket, which competes with –GGGC chelator and makes its use impossible [33]. It was, thus, not a given that the re-engineered HER2-specific affibody scaffold would be compatible with stable labelling with 99mTc using a –GGGC chelating sequence.

2. Researchs and Discussions

Radionuclide molecular imaging has the apparent potential to make targeted cancer treatment more personalized by identifying patients who have tumours with a sufficiently high target expression level. The 68Ga-labelled affibody molecule ABY-025 has already demonstrated that the technology can be used for PET imaging of HER2 expression with high specificity and sensitivity [20]. However, PET has limited availability while SPECT imaging is much more available. In addition, the progress in detector engineering and software development makes SPECT/CT an increasingly attractive imaging modality. Modern SPECT/CT cameras provide spatial resolution of about 5.5 mm and quantification accuracy of 5%. Importantly, such cameras remain to be cheaper than PET/CT scanners. Moreover, the use of 99mTc-generators makes the process of radiopharmaceutical production appreciably cheaper, as an installation of a cyclotron is not required. This created a strong motivation for an introduction of affibody-based imaging probes for SPECT into clinics.

Previous preclinical research resulted in development of the [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2 affibody molecules with very attractive imaging properties [17]. However, this tracer utilizes an original affibody scaffold. Apparently, it would be much more appealing to perform a clinical development program using a new, improved scaffold, which provides a better yield in peptide synthesis, higher stability, and lower binding to blood proteins [19]. Therefore, ZHER2:41071, which is a new variant of the HER2-binding affibody molecule, has been designed. It has the same composition of the binding site as ZHER2:V2, but is based on a re-engineered scaffold. In addition, an NDA-sequence close to the C-terminus was replaced by –SES– to further improve peptide stability and increase hydrophilicity of the affibody molecule. The –GGGC chelator was kept at the C-terminus to provide low retention in the kidney (Figure 1). The good in vitro characteristics of ZHER2:V2 were shown to be kept with ZHER2:41071. The two molecules also showed good stability up to six months at −80 °C to 5 °C, but ZHER2:41071 was more stable after heat treatment, according to the labelling protocol (90 °C at 60 min), which might be due to the replacement of the -NDA-sequence by –SES mentioned above. Re-engineering of the scaffold used for ZHER2:41071 was also shown to reduce the number of potential immunogenic epitopes calculated by a program used for in silico immunogenicity prediction. Although MHCII binding is only one determinant of immunogenicity and might also depend on the particular MHCII allele, such an approach enables us to identify and eliminate potential immunogenicity of protein therapeutics [34]. The modification of the scaffold was very profound, and this could be associated with undesirable changes of properties, such as loss of site specificity of labelling and in negative changes in biodistribution and imaging properties, as discussed in the introduction. Therefore, a clinical translational program would require a new preclinical evaluation of the new improved tracer to make sure that the modifications in the scaffold had no undesirable effects.

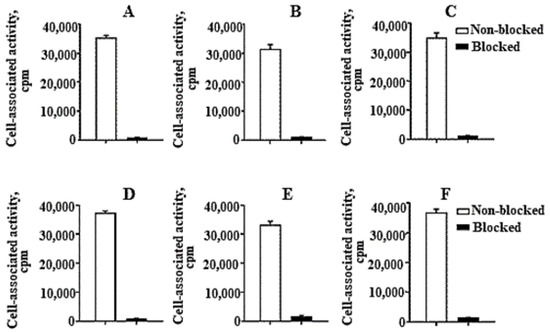

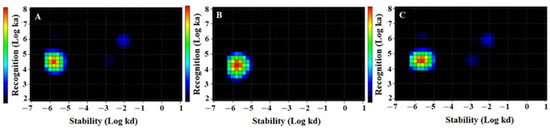

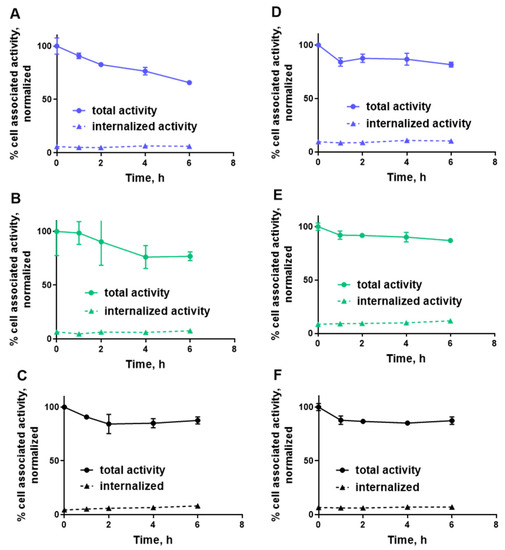

In contrast with our concern that a change of several amino acids in the scaffold, especially the introduction of serines, would decrease the labelling efficiency and the beneficial reduction of kidney uptake, and also in contrast from our previous experience with an EGFR-specific affibody molecule where stable labelling could not be achieved with the same chelating sequence [33], it turned out that the effect of the scaffold modifications in this case was minor. The labelling of all tested variants was equally efficient and stable (Table 1). [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071 binding to both HER2-expressing cell lines was highly specific and the specificity was as high as for previously studied HER2-binding affibody molecules (Figure 2). The high affinity of binding to living HER2-expressing cells was preserved (Figure 3 and Table 2) and was even slightly higher than the affinity of [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2. Estimation of the internalization rate is reliable only in the case of a residualizing label, as leakage of radio-metabolites does not lead to underestimation of internalized activity. In vitro data for [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:2395 (with a residualizing label) demonstrated very low internalized activity for 6 h in both tested cell-lines (Figure 4A,B). Therefore, it is explained that the retention of activity of both variants with non-residualizing labels, [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071 and [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2, was nearly as efficient as the retention of [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:2395. When the internalization rate is slow, leaking intracellular radio-metabolites make little difference in overall retention, which is mainly determined by strong binding to a membranous protein.

Table 1. Radiolabelling of affibody molecules with 99mTc and stability of the conjugate.

| Compound | Radio-Labelling Yield, % | Stability in PBS, % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h | 4 h | ||

| ZHER2:2395 | 98.6 ± 1.4 | 96.2 ± 0.8 | 97.1 ± 0.4 |

| ZHER2:41071 | 95.6 ± 2.7 | 98.7 ± 0.7 | 97.5 ± 0.9 |

| ZHER2:V2 | 96.3 ± 1.9 | 98.1 ± 0.2 | 97.2 ± 0.3 |

Figure 2. In vitro binding specificity of (A,D) [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071, (B,E) [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2 and (C,F) [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:2395 to HER2-expressing SKOV3 (A–C) and BT-474 (D–F) cell-lines. For the pre-saturation of HER2, a 500-fold molar excess of a non-radioactive affibody molecule was added. The data are presented as an average value from three samples ± SD.

Figure 3. Interaction Map of (A) [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:2395, (B) [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071. and (C) [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2 binding to HER2-expressing SKOV3 cells. Input data are obtained from LigandTracer measurement of cell-bound activity during association of labelled compounds to and dissociation from SKOV-3 cells. InteractionMap finds individual 1:1 interactions in the input data whose weighted sum explain the observed binding process. The individual interactions are displayed as coloured spots in a ka/kd plot with their colour representing their weight: warmer colours represent more abundant interactions. Binding was measured at three different concentrations: 0.33, 1, and 3 nM. The measurement was performed in duplicates.

Table 2. Apparent equilibrium dissociation (KD) constants for the interaction between [99mTc]Tc-labelled affibody molecules and HER2-expressing SKOV3 cells determined using an Interaction Map analysis of the LigandTracer sensorgrams.

| Label | ka (1/M×s) × 104 | kd (1/s) × 10−6 | KD (pM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:2395 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 1.50 ± 0.05 | 53 ± 4 |

| [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 2.17 ± 0.05 | 58 ± 2 |

| [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 90 ± 22 |

Figure 4. Normalized cellular retention of (A,D) [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071, (B,E) [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2 and (C,F) [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:2395 to HER2-expressing SKOV3 (A–C) and BT-474 (D–F) cell-lines. The data are presented as an average (n = 3) and SD. Error bars are not seen because they are smaller than point symbols.

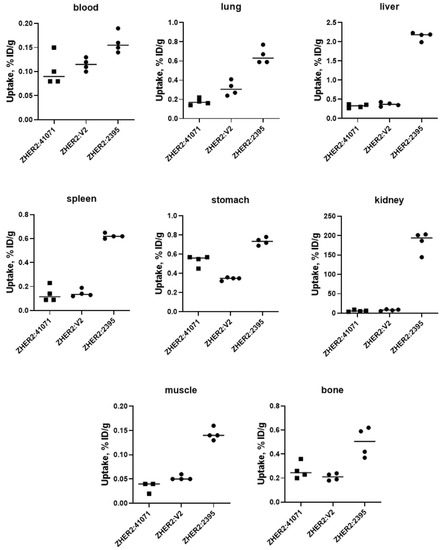

A pilot experiment in normal mice (Figure 5) demonstrated that [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071 and [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2 share multiple biodistribution features. The most conspicuous was the 25–30-fold lower renal uptake of these two affibody molecules compared to [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:2395. The uptake of [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071 and [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2 in liver was also four-fold lower compared with [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:2395. This is a favourable feature, as it results in reduced background activity for imaging of liver metastases, which is a frequent challenge in breast cancer. Most likely, the phenomenon of improved biodistribution is caused by the non-residualizing properties of the [99mTc](Tc=O)–GGGC label. The renal reabsorption of affibody molecules causes a rapid internalization and intracellular degradation. Apparently, this process is rapid, and radio-metabolites of non-residualizing labels are eliminated from kidneys by diffusion through lysosomal and cellular membranes [13]. There is always a non-specific binding in normal tissues, which is first and foremost in liver. Analysis of data from previous studies [15][16] shows that affibody molecules with non-residualizing labels have rapid clearance of activity from the liver. It is reasonable to suppose that the hepatic uptake is also associated with quite rapid internalization and lysosomal degradation, leading to a release of non-residualizing labels. Overall, the use of a non-residualizing label resulted in reduced uptake in normal organs and tissues.

Figure 5. Uptake of 99mTc-labelled affibody molecules in different organs of female NMRI mice at 4 h after injection. Then, 1 µg of labelled affibody molecules (60 kBq, 100 µL in PBS) was injected into the tail vein.

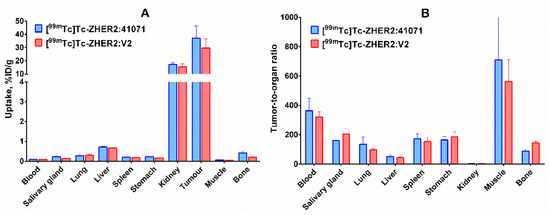

Uptake of [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071 in HER2-positive SKOV-3 xenografts was 175-fold higher (p < 0.0005) than in HER2-negative Ramos xenografts (Figure 5 and Figure 6), which clearly demonstrates HER2-specificity of targeting. In mice bearing SKOV-3 xenografts, [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071 and [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2 has very similar biodistribution and targeting profiles, and demonstrated similar tumour-to-organ ratios (Figure 6). Thus, a fundamental scaffold modification did not negatively influence the imaging properties of [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071. An evaluation of absorbed doses for humans demonstrated very favourable dosimetry with an effective dose of 0.00066 mSv/MBq (Table 3). For comparison, the effective dose for 111In-trastuzumab was 0.19 ± 0.02 mSv/MBq [35], for 99mTc-labelled scaffold protein ADAPT6 0.010 ± 0.003 mSv/MBq [36], and for 68Ga-labelled anti-HER2 Affibody molecule ABY-025 0.030 ± 0.003 mSv/MBq [21]. To a high extent, this was determined by low retention of activity in liver and kidneys as well as a short residence time in the whole body.

Figure 6. (A) Biodistribution and (B) tumor-to-organ ratios of selected conjugates, [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071 and [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:V2, in BALB/C nu/nu mice bearing HER2-expressing SKOV3 xenografts 4 h after injection. The data are presented as the average value (n = 4) and SD.

Table 3. Calculated absorbed dose (mGy/MBq) for [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071 in humans using OLINDA/EXM 1.0.

| Organ | Absorbed Dose (mGy/MBq) | Organ | Absorbed Dose (mGy/MBq) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adrenals | 0.0009 | Muscle | 0.00034 |

| Brain | 0.00016 | Ovaries | 0.00042 |

| Breasts | 0.00029 | Pancreas | 0.00073 |

| Gallbladder wall | 0.0007 | Red marrow | 0.00062 |

| Lower large intestine wall | 0.0004 | Osteogenic cells | 0.0026 |

| Small intestine | 0.00049 | Skin | 0.00021 |

| Stomach wall | 0.00052 | Spleen | 0.00078 |

| Upper large intestine wall | 0.0005 | Thymus | 0.00049 |

| Heart wall | 0.00160 | Thyroid | 0.00029 |

| Kidney | 0.0069 | Urinary bladder wall | 0.00037 |

| Liver | 0.00088 | Uterus | 0.00051 |

| Lungs | 0.0007 | Total body | 0.00048 |

The comparison of a newly developed imaging probe with the probes developed earlier requires selection of an informative characteristic. Such a characteristic is the imaging contrast provided by a probe. Often, tumour-to-blood ratio is a measure of contrast as blood-born activity contributes to the background. A high imaging contrast is essential for visualization of small metastases, when the partial volume effect results in decreased imaging sensitivity [37]. Therefore, imaging probes with the highest possible imaging contrast are required. There was intense preclinical research aimed at development of SPECT imaging agents based on HER2-targeted therapeutic antibodies trastuzumab [38][39][40] and pertuzumab [41]. Due to bulkiness of intact immunoglobulins (molecular weigh 150 kDa), the tumour-to-blood ratio in murine models was lower than 10 even 72 h after injection. In addition, appreciable unspecific uptake of immunoglobulins in tumours indicated that the imaging specificity might be compromised [38][39]. The low contrast was associated with a low sensitivity in clinics. The maximum contrast of 111In-trastuzumab imaging in the clinic was achieved for the first time 168 h after injection [34]. Still, the detection rate of single tumour lesions was 45% [9]. The use of smaller (55 kDa) 111In-labelled Fab-fragments of trastuzumab enabled us to reach a tumour-to-blood ratio of 10 at 24 h after injection [42]. Single domain antibodies (sdAb, nanobody) with a molecular weight of 15 kDa were used to develop the smallest immunoglobulin-based HER2-specific imaging probes for SPECT and provided tumour-to-blood ratios in the range of 10–16 1.5 h after injection [43][44].

The use of scaffold proteins permitted us to decrease the size and, thereby, further increase the imaging contrast provided by probes for SPECT visualization of HER2. In mouse models, tumor-to-blood ratios 4 h after injection ranged from 50 to 200 obtained using DARPins [45][46], were around 100 for ADAPTs [46], and ranged from 100–200 for affibody molecules [16][17][29]. [99mTc]Tc-ZHER2:41071 provided the tumour-to-blood ratio of 363 ± 84 in this study, which is the best value provided by a SPECT imaging probe for HER2 so far.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22052770

References

- Slamon, D.J.; Clark, G.M.; Wong, S.G.; Levin, W.J.; Ullrich, A.; McGuire, W.L. Human breast cancer: Correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neuoncogene. Science 1987, 235, 177–182.

- Hynes, N.E.; Lane, H.A. ERBB receptors and cancer: The complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 341–354.

- Bang, Y.J.; Van Cutsem, E.; Feyereislova, A.; Chung, H.C.; Shen, L.; Sawaki, A.; Lordick, F.; Ohtsu, A.; Omuro, Y.; Satoh, T.; et al. ToGA Trial Investigators. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): A phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 687–697.

- Loibl, S.; Gianni, L. HER2-positive breast cancer. Lancet 2017, 389, 2415–2429.

- Wolff, A.C.; Hammond, M.E.; Hicks, D.G.; Dowsett, M.; McShane, L.M.; Allison, K.H.; Allred, D.C.; Bartlett, J.M.S.; Bilous, M.; Fitzgibbons, P.; et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 3997–4013.

- Seol, H.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, Y.; Lee, H.E.; Kim, Y.J.; Kang, E.; Kim, S.W.; Park, S.Y. Intratumoral heterogeneity of HER2 gene amplification in breast cancer: Its clinicopathological significance. Mod. Pathol. 2012, 25, 938–948.

- Niikura, N.; Tomotaki, A.; Miyata, H.; Iwamoto, T.; Kawai, M.; Anan, K.; Hayashi, N.; Aogi, K.; Ishida, T.; Masuoka, H.; et al. Changes in tumor expression of HER2 and hormone receptors status after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in 21,755 patients from the Japanese breast cancer registry. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 480–487.

- Behr, T.M.; Behe, M.; Wormann, B. Trastuzumab and breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 995–996.

- Perik, P.J.; Lub-De Hooge, M.N.; Gietema, J.A.; van der Graaf, W.T.A.; de Korte, M.A.; Jonkman, A.; Kosterink, J.G.W.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Sleijfer, D.T.; Jager, P.L.; et al. Indium-111-labeled trastuzumab scintigraphy in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 2276–2282.

- Gebhart, G.; Flamen, P.; De Vries, E.G.; Jhaveri, K.; Wimana, Z. Imaging Diagnostic and Therapeutic Targets: Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57 (Suppl. 1), 81S–88S.

- Garousi, J.; Orlova, A.; Frejd, F.Y.; Tolmachev, V. Imaging using radiolabelled targeted proteins: Radioimmunodetection and beyond. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2020, 5, 16.

- Krasniqi, A.; D’Huyvetter, M.; Devoogdt, N.; Frejd, F.Y.; Sörensen, J.; Orlova, A.; Keyaerts, M.; Tolmachev, V. Same-Day Imaging Using Small Proteins: Clinical Experience and Translational Prospects in Oncology. J. Nucl. Med. 2018, 59, 885–891.

- Tolmachev, V.; Orlova, A. Affibody Molecules as Targeting Vectors for PET Imaging. Cancers 2020, 12, 651.

- Ståhl, S.; Gräslund, T.; Karlström, A.E.; Frejd, F.Y.; Nygren, P.Å.; Löfblom, J.; Tolmachev, V.; Orlova, A. Affibody Molecules in Biotechnological and Medical Applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 691–712.

- Orlova, A.; Magnusson, M.; Eriksson, T.; Nilsson, M.; Larsson, B.; Höiden-Guthenberg, I.; Widstrom, C.; Carlsson, J.; Tolmachev, V.; Stahl, S.; et al. Tumor imaging using a picomolar affinity HER-2 binding affibody molecules. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 4339–4348.

- Ahlgren, S.; Wållberg, H.; Tran, T.A.; Widström, C.; Hjertman, M.; Abrahmsén, L.; Berndorff, D.; Dinkelborg, L.M.; Cyr, J.E.; Feldwisch, J.; et al. Targeting of HER2-expressing tumors with a site-specifically 99mTc-labeled recombinant Affibody molecule, ZHER2:2395, with C-terminally engineered cysteine. J. Nucl. Med. 2009, 50, 781–789.

- Wållberg, H.; Orlova, A.; Altai, M.; Hosseinimehr, S.J.; Widström, C.; Malmberg, J.; Ståhl, S.; Tolmachev, V. Molecular design and optimization of 99mTc-labeled recombinant affibody molecules improves their biodistribution and imaging properties. J. Nucl. Med. 2011, 52, 461–469.

- Baum, R.P.; Prasad, V.; Müller, D.; Schuchardt, C.; Orlova, A.; Wennborg, A.; Tolmachev, V.; Feldwisch, J. Molecular imaging of HER2-expressing malignant tumors in breast cancer patients using synthetic 111In- or 68Ga-labeled affibody molecules. J. Nucl. Med. 2010, 51, 892–897.

- Feldwisch, J.; Tolmachev, V.; Lendel, C.; Herne, N.; Sjöberg, A.; Larsson, B.; Rosik, D.; Lindqvist, E.; Fant, G.; Höidén-Guthenberg, I.; et al. Design of an optimized scaffold for affibody molecules. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 398, 232–247.

- Sörensen, J.; Velikyan, I.; Sandberg, D.; Wennborg, A.; Feldwisch, J.; Tolmachev, V.; Orlova, A.; Sandström, M.; Lubberink, M.; Olofsson, H.; et al. Measuring HER2-Receptor Expression In Metastatic Breast Cancer Using [68Ga]ABY-025 Affibody PET/CT. Theranostics 2016, 6, 262–271.

- Sandström, M.; Lindskog, K.; Velikyan, I.; Wennborg, A.; Feldwisch, J.; Sandberg, D.; Tolmachev, V.; Orlova, A.; Sörensen, J.; Carlsson, J. Biodistribution and Radiation Dosimetry of the Anti-HER2 Affibody Molecule 68Ga-ABY-025 in Breast Cancer Patients. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 867–871.

- Sörensen, J.; Sandberg, D.; Sandström, M.; Wennborg, A.; Feldwisch, J.; Tolmachev, V.; Åström, G.; Lubberink, M.; Garske-Román, U.; Carlsson, J.; et al. First-in-human molecular imaging of HER2 expression in breast cancer metastases using the 111In-ABY-025 affibody molecule. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 730–735.

- Duatti, A. Review on 99mTc radiopharmaceuticals with emphasis on new advancements. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2020, 92, 202–216.

- Hofström, C.; Altai, M.; Honarvar, H.; Strand, J.; Malmberg, J.; Hosseinimehr, S.J.; Orlova, A.; Gräslund, T.; Tolmachev, V. HAHAHA, HEHEHE, HIHIHI, or HKHKHK: Influence of position and composition of histidine containing tags on biodistribution of [(99m)Tc(CO)3](+)-labeled affibody molecules. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 4966–4974.

- Engfeldt, T.; Tran, T.; Orlova, A.; Widström, C.; Karlstroöm, E.A.; Tolmachev, V. 99mTc-chelator engineering to improve tumour targeting properties of a HER2-specific Affibody molecule. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2007, 34, 1843–1853.

- Tran, T.; Engfeldt, T.; Orlova, A.; Sandström, M.; Feldwisch, J.; Abrahmsén, L.; Wennborg, A.; Tolmachev, V.; Karlström, A.E. 99mTc-maEEE-ZHER2:342, an Affibodymolecule-based tracer for detection of HER2-expression in malignant tumors. Bioconjug. Chem. 2007, 18, 1956–1964.

- Ekblad, T.; Tran, T.; Orlova, A.; Widström, C.; Feldwisch, J.; Abrahmsén, L.; Wennborg, A.; Karlström, A.E.; Tolmachev, V. Development and preclinical characterisationof 99mTc-labelled Affibody molecules with reduced renal uptake. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2008, 35, 2245–2255.

- Tran, T.A.; Rosik, D.; Abrahmsén, L.; Sandström, M.; Sjöberg, A.; Wållberg, H.; Ahlgren, S.; Orlova, A.; Tolmachev, V. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of a HER2-specific affibody molecule for molecular imaging. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2009, 36, 1864–1873.

- Ahlgren, S.; Andersson, K.; Tolmachev, V. Kit formulation for 99mTc-labeling of recombinant anti-HER2 affibody molecules with a C-terminally engineered cysteine. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2010, 37, 539–546.

- Altai, M.; Wållberg, H.; Orlova, A.; Rosestedt, M.; Hosseinimehr, S.J.; Tolmachev, V.; Ståhl, S. Order of amino acids in C-terminal cysteine-containing peptide-based chelators influences cellular processing and biodistribution of 99mTc-labeled recombinant Affibody molecules. Amino Acids 2012, 5, 1975–1985.

- Cyr, J.E.; Koppitz, M.; Srinivasan, A.; Dinkelborg, L.M. Improved peptide chelators for Tc/Re(V); stabilizing side chains [abstract]. J. Labelled Comp. Radiopharm. 2007, 50, S9.

- Lindberg, H.; Hofström, C.; Altai, M.; Honorvar, H.; Wållberg, H.; Orlova, A.; Ståhl, S.; Gräslund, T.; Tolmachev, V. Evaluation of a HER2-targeting affibody molecule combining an N-terminal HEHEHE-tag with a GGGC chelator for 99mTc-labelling at the C terminus. Tumour Biol. 2012, 33, 641–651.

- Oroujeni, M.; Andersson, K.G.; Steinhardt, X.; Altai, M.; Orlova, A.; Mitran, B.; Vorobyeva, A.; Garousi, J.; Tolmachev, V.; Löfblom, J. Influence of composition of cysteine-containing peptide-based chelators on biodistribution of 99mTc-labeled anti-EGFR affibody molecules. Amino Acids 2018, 50, 981–994.

- Rosenberg, A.S.; Sauna, Z.E. Immunogenicity assessment during the development of protein therapeutics. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2018, 70, 584–594.

- Gaykema, S.B.; de Jong, J.R.; Perik, P.J.; Brouwers, A.H.; Schröder, C.P.; Oude Munnink, T.H.; Bongaerts, A.H.; de Vries, E.G.; Lub-de Hooge, M.N. (111)In-trastuzumab scintigraphy in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients remains feasible during trastuzumab treatment. Mol. Imaging 2014, 13.

- Bragina, O.; von Witting, E.; Garousi, J.; Zelchan, R.; Sandström, M.; Medvedeva, A.; Orlova, A.; Doroshenko, A.; Vorobyeva, A.; Lindbo, S.; et al. Phase I study of 99mTc-ADAPT6, a scaffold protein-based probe for visualization of HER2 expression in breast cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 120.

- Eckelman, W.C.; Kilbourn, M.R.; Mathis, C.A. Specific to nonspecific binding in radiopharmaceutical studies: It’s not so simple as it seems! Nucl. Med. Biol. 2009, 36, 235–237.

- Lub-de Hooge, M.N.; Kosterink, J.G.; Perik, P.J.; Nijnuis, H.; Tran, L.; Bart, J.; Suurmeijer, A.J.; de Jong, S.; Jager, P.L.; de Vries, E.G. Preclinical characterisation of 111In-DTPA-trastuzumab. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 143, 99–106.

- McLarty, K.; Cornelissen, B.; Scollard, D.A.; Done, S.J.; Chun, K.; Reilly, R.M. Associations between the uptake of 111In-DTPA-trastuzumab, HER2 density and response to trastuzumab (Herceptin) in athymic mice bearing subcutaneous human tumour xenografts. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2009, 36, 81–93.

- Milenic, D.E.; Wong, K.J.; Baidoo, K.E.; Nayak, T.K.; Regino, C.A.; Garmestani, K.; Brechbiel, M.W. Targeting HER2: A report on the in vitro and in vivo pre-clinical data supporting trastuzumab as a radioimmunoconjugate for clinical trials. MAbs 2010, 2, 550–564.

- McLarty, K.; Cornelissen, B.; Cai, Z.; Scollard, D.A.; Costantini, D.L.; Done, S.J.; Reilly, R.M. Micro-SPECT/CT with 111In-DTPA-pertuzumab sensitively detects trastuzumab-mediated HER2 downregulation and tumor response in athymic mice bearing MDA-MB-361 human breast cancer xenografts. J. Nucl. Med. 2009, 50, 1340–1348.

- Chan, C.; Scollard, D.A.; McLarty, K.; Smith, S.; Reilly, R.M. A comparison of 111In- or 64Cu-DOTA-trastuzumab Fab fragments for imaging subcutaneous HER2-positive tumor xenografts in athymic mice using microSPECT/CT or microPET/CT. EJNMMI Res. 2011, 1, 15.

- Vaneycken, I.; Devoogdt, N.; Van Gassen, N.; Vincke, C.; Xavier, C.; Wernery, U.; Muyldermans, S.; Lahoutte, T.; Caveliers, V. Preclinical screening of anti-HER2 nanobodies for molecular imaging of breast cancer. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 2433–2446.

- Massa, S.; Xavier, C.; De Vos, J.; Caveliers, V.; Lahoutte, T.; Muyldermans, S.; Devoogdt, N. Site-specific labeling of cysteine-tagged camelid single-domain antibody-fragments for use in molecular imaging. Bioconjug. Chem. 2014, 25, 979–988.

- Goldstein, R.; Sosabowski, J.; Livanos, M.; Leyton, J.; Vigor, K.; Bhavsar, G.; Nagy-Davidescu, G.; Rashid, M.; Miranda, E.; Yeung, J.; et al. Development of the designed ankyrin repeat protein (DARPin) G3 for HER2 molecular imaging. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2015, 2, 288–301.

- Vorobyeva, A.; Schulga, A.; Konovalova, E.; Güler, R.; Löfblom, J.; Sandström, M.; Garousi, J.; Chernov, V.; Bragina, O.; Orlova, A.; et al. Optimal composition and position of histidine-containing tags improves biodistribution of (99m)Tc-labeled DARPin G3. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9405.