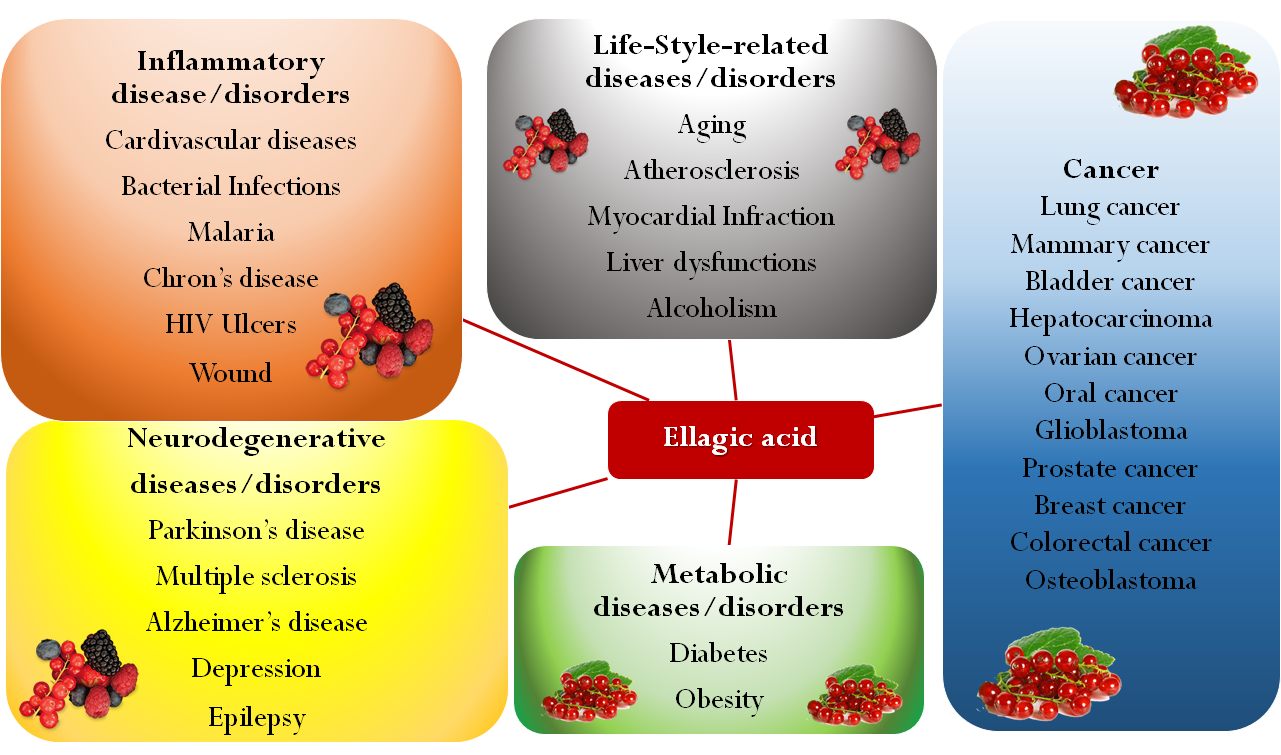

Ellagic acid, a polyphenolic compound present in fruit and berries, has recently been the object of extensive research for its antioxidant activity, which might be useful for the prevention and treatment of cancer, cardiovascular pathologies, and neurodegenerative disorders. Its protective role justifies numerous attempts to include it in functional food preparations and in dietary supplements, and not only to limit the unpleasant collateral effects of chemotherapy. However, ellagic acid use as a chemopreventive agent has been debated because of its poor bioavailability associated with low solubility, limited permeability, first pass effect, and interindividual variability in gut microbial transformations. To overcome these drawbacks, various strategies for oral administration including solid dispersions, micro and nanoparticles, inclusion complexes, self-emulsifying systems, and polymorphs were proposed. Here, we listed an updated description of pursued micro and nanotechnological approaches focusing on the fabrication processes and the features of the obtained products, as well as on the positive results yielded by in vitro and in vivo studies in comparison to the raw material. The micro and nanosized formulations here described might be exploited for pharmaceutical delivery of this active, as well as for the production of nutritional supplements or for the enrichment of novel foods.

- ellagic acid

- oral administration

- bioavailability

- microformulations

- nanoformulations

- solubility enhancement

Introduction

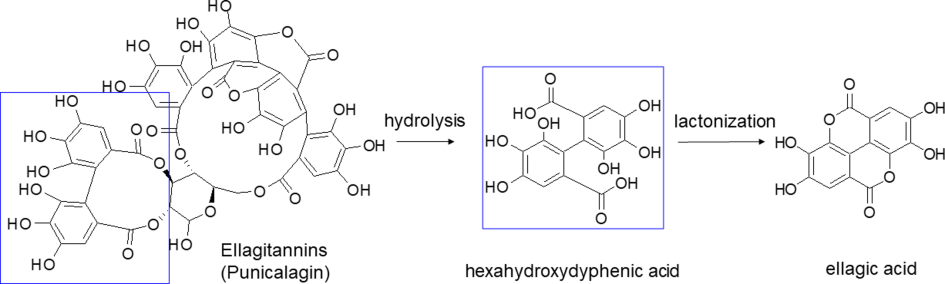

EA Chemical Structure and Solubility

| Vehicles | Solubility (mg/mL) | Temperature | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone | 25 | 37 °C | |

| DMSO | 2.5 | 37 °C | |

| Pyridine | 2.0 | 37 °C | |

| Methanol | (671 ± 17) × 10−3 | 37 °C | |

| Ethanol | 1.02 ± 0.04 | 25 °C | |

| PEG 200 | 4.178 | 25 °C | |

| PEG 400 | 11.0 ± 0.5 | 25 °C | |

| Propylene glycol | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 25 °C | |

| Palmester 3575 | 0.030 | 25 °C | |

| Cottonseed oil | 0.005 | 25 °C | |

| Soybean oil | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 25 °C | |

| Castor oil | 1.63 ± 0.07 | 25 °C | |

| Oleic acid | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 25 °C | |

| Ethyl oleate | 2.34 ± 0.06 | 25 °C | |

| Tween 20 | 1.605 | 25 °C | |

| Sucrose esters | 0.115 | 25 °C | |

| Isopropyl myristate | 1.94 ± 0.07 | 25 °C | |

| Cremophor RH40 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 25 °C | |

| Tween 80 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 25 °C | |

| Lecithin | 0.085 ± 0.004 | 25 °C | |

| Poloxamer F68 | 0.036 ± 0.002 | 25 °C | |

| Phosphate buffer pH 7.4 | (33 ± 16) × 10−3 | 37 °C | |

| Phosphate buffer pH 6.8 | (11.1 ± 0.4) × 10−3 | 25 °C | |

| Acetate buffer pH 4.5 | (6.9 ± 0.3) × 10−3 | 25 °C | |

| Distilled water | (8.2 ± 0.4) × 10−3 | 25 °C | |

| HCl 0.1 M in water | (1.03 ± 0.06) × 10−3 | 25 °C |

References

- Miguel, M.G.; Neves, M.A.; Antunes, M.D. Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.): A medicinal plant with myriad biological properties—A short review. J. Med. Plants Res. 2010, 4, 2836–2847. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos, J.L.; Giner, R.M.; Marín, M.; Recio, M.C. A Pharmacological Update of Ellagic Acid. Planta Med. 2018, 84, 1068–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, N.G.; Shi, Z.; Qiu, J.; He, C.; Chen, M. Recent Advances in Anticancer Activities and Drug Delivery Systems of Tannins. Med. Res. Rev. 2017, 37, 665–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahangarpour, A.; Sayahi, M.; Sayahi, M. The antidiabetic and antioxidant properties of some phenolic phytochemicals: A review study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. 2019, 13, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baradaran Rahimi, V.; Ghadiri, M.; Ramezani, M.; Askari, V.R. Anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities of pomegranate and its constituent, ellagic acid: Evidence from cellular, animal, and clinical studies. Phytother. Res. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Turrini, F.; Catena, S.; Zunin, P.; Grilli, M.; Pittaluga, A.M.; Boggia, R. Ellagic acid a multi-target bioactive compound for drug discovery in CNS? A narrative review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 183, 111724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, I.; Buckner, T.; Shay, N.F.; Gu, L.; Chung, S. Improvements in Metabolic Health with Consumption of Ellagic Acid and Subsequent Conversion into Urolithins: Evidence and Mechanisms. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkaki, A.; Farbood, Y.; Dolatshahi, M.; Mansouri, S.M.; Khodadadi, A. Neuroprotective Effects of Ellagic Acid in a Rat Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Acta Med. Iran. 2016, 54, 494–502. [Google Scholar]

- Das, U.; Biswas, S.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Chakraborty, A.; Dey Sharma, R.; Banerji, A.; Dey, S. Radiosensitizing effect of ellagic acid on growth of Hepatocellular carcinoma cells: An in vitro study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Phan, A.N.H.; Choi, J.W. Anti-cancer Effects of Polyphenolic Compounds in Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor-resistant Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2017, 13, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanella, L.; Di Giacomo, C.; Acquaviva, R.; Barbagallo, I.; Li Volti, G.; Cardile, V.; Abraham, N.; Sorrenti, V. Effects of Ellagic Acid on Angiogenic Factors in Prostate Cancer Cells. Cancers 2013, 5, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Z.; Nair, V.; Khan, M.; Ciolino, H.P. Pomegranate extract inhibits the proliferation and viability of MMTV-Wnt-1 mouse mammary cancer stem cells in vitro. Oncol. Rep. 2010, 24, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowshik, J.; Giri, H.; Kishore, T.; Kesavan, R.; Vankudavath, R.; Reddy, G.; Dixit, M.; Nagini, S. Ellagic Acid Inhibits VEGF/VEGFR2, PI3K/Akt and MAPK Signaling Cascades in the Hamster Cheek Pouch Carcinogenesis Model. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2014, 14, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceci, C.; Tentori, L.; Atzori, M.; Lacal, P.; Bonanno, E.; Scimeca, M.; Cicconi, R.; Mattei, M.; de Martino, M.; Vespasiani, G.; et al. Ellagic Acid Inhibits Bladder Cancer Invasiveness and In Vivo Tumor Growth. Nutrients 2016, 8, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, T.; Mastriani, E.; Li, Q.H.; Bao, H.X.; Zhou, Y.J.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Main components of pomegranate, ellagic acid and luteolin, inhibit metastasis of ovarian cancer by down-regulating MMP2 and MMP9. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2017, 18, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, Q.; Tan, Y.; Liu, B.; Liu, C. Ellagic acid inhibits human glioblastoma growth in vitro and in vivo. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Xu, J.; Wang, T.; Liu, W.; Wei, H.; Yang, X.; Yan, W.; Zhou, W.; Xiao, J. Ellagic acid and Sennoside B inhibit osteosarcoma cell migration, invasion and growth by repressing the expression of c-Jun. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, C.; Lacal, P.; Tentori, L.; De Martino, M.; Miano, R.; Graziani, G. Experimental Evidence of the Antitumor, Antimetastatic and Antiangiogenic Activity of Ellagic Acid. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umesalma, S.; Nagendraprabhu, P.; Sudhandiran, G. Ellagic acid inhibits proliferation and induced apoptosis via the Akt signaling pathway in HCT-15 colon adenocarcinoma cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 399, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, Y.; Koul, A.; Ranawat, P. Ellagic acid ameliorates cisplatin induced hepatotoxicity in colon carcinogenesis. Environ. Toxicol. 2019, 34, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Yin, M. Preventive Effects of Ellagic Acid Against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardio-Toxicity in Mice. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2013, 13, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonaje, K.; Italia, J.L.; Sharma, G.; Bhardwaj, V.; Tikoo, K.; Kumar, M.N.V.R. Development of Biodegradable Nanoparticles for Oral Delivery of Ellagic Acid and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Efficacy Against Cyclosporine A-Induced Nephrotoxicity in Rats. Pharm. Res. 2007, 24, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepúlveda, L.; Ascacio, A.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Aguilera-Carbó, A.; Aguilar, C.N. Ellagic acid biological properties and biotechnological development. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 4518–4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notka, F.; Meier, G.; Wagner, R. Concerted inhibitory activities of Phyllanthus amarus on HIV replication in vitro and ex vivo. Antivir. Res. 2004, 64, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, R.; Vijayakumar, M.; Rao, C.V.; Shirwaikar, A.; Mehrotra, S.; Pushpangadan, P. Healing potential of Anogeissus latifolia for dermal wounds in rats. Acta Pharm. 2004, 54, 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Giménez-Bastida, J.A.; González-Sarrías, A.; Larrosa, M.; Tomás-Barberán, F.; Espín, J.C.; García-Conesa, M.T. Intestinal ellagitannin metabolites ameliorate cytokine-induced inflammation and associated molecular markers in human colon fibroblasts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 8866–8876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabha, B.; Sini, S.; Priyadarshini, T.S.; Sasikumar, P.; Gopalan, G.; Jayesh, P.J.; Jithin, M.M.; Sivan, V.V.; Jayamurthy, P.; Radhakrishnan, K.V. Anti-inflammatory effect and mechanism of action of ellagic acid-3,3’,4-trimethoxy-4’-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside isolated from Hopea parviflora in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, L.; Mena, P.; Piemontese, A.; Marino, V.; López-Gutiérrez, N.; Bernini, F.; Brighenti, F.; Zanotti, I.; Del Rio, D. Antiatherogenic effects of ellagic acid and urolithins in vitro. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016, 599, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, J.B.R.; Porto, H.K.P.; Lopes, F.M.; Batista, A.C.; Rocha, M.L. Protective Effects of Ellagic Acid on Cardiovascular Injuries Caused by Hypertension in Rats. Planta Med. 2017, 83, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrini, F.; Boggia, R.; Donno, D.; Parodi, B.; Beccaro, G.; Baldassari, S.; Signorello, M.G.; Catena, S.; Alfei, S.; Zunin, P. From pomegranate marcs to a potential bioactive ingredient: A recycling proposal for pomegranate squeezed-marcs. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 246, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, K.H.; Han, C.S.; Yang, H.C.; Park, S.H.; Jang, H.-I.; Kim, J.-W.; Choi, Y.-S.; Lee, N.H. Anti-wrinkle activity of Platycarya strobilacea extract and its application as a cosmeceutical ingredient. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2018, 14, 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Li, J.; Cheng, Y.; Huo, T.; Xue, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, X. Effects of ellagic acid-rich extract of pomegranates peel on regulation of cholesterol metabolism and its molecular mechanism in hamsters. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggia, R.; Turrini, F.; Villa, C.; Lacapra, C.; Zunin, P.; Parodi, B. Green extraction from pomegranate marcs for the production of functional foods and cosmetics. Pharmaceuticals 2016, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez-Sánchez, M.A.; García-Villalba, R.; Monedero-Saiz, T.; GarcíaTalavera, N.V.; Gómez-Sánchez, M.B.; Sánchez-Álvarez, C.; García-Albert, A.M.; Rodríguez-Gil, F.J.; Ruiz-Marín, M.; Pastor-Quirante, F.A.; et al. Targeted metabolic profiling of pomegranate polyphenols and urolithins in plasma, urine and colon tissues from colorectal cancer patients. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 1199–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellone, J.A.; Murray, J.R.; Jorge, P.; Fogel, T.G.; Kim, M.; Wallace, D.R.; Hartman, R.E. Pomegranate supplementation improves cognitive and functional recovery following ischemic stroke: A randomized trial. Nutr. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bala, I.; Bhardwaj, V.; Hariharan, S.; Kumar, M.N. Analytical methods for assay of ellagic acid and its solubility studies. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2006, 40, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzolf, M.; Szymusiak, H.; Gliszczynska-Swiglo, A.; Rietjens, I.M.C.M.; Tyrakowska, B. pH-Dependent radical scavenging capacity of green tea catechins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panichayupakaranant, P.; Itsuriya, A.; Sirikatitham, A. Preparation method and stability of ellagic acid-rich pomegranate fruit peel extract. Pharm. Biol. 2010, 48, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/app10103353