Herpesviruses are the causative agents of several diseases. Infections are generally mild or asymptomatic in immunocompetent individuals. In contrast, herpesvirus infections continue to contribute to significant morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients. Few drugs are available for the treatment of human herpesvirus infections, mainly targeting the viral DNA polymerase. Moreover, no successful therapeutic options are available for the Epstein–Barr virus or human herpesvirus 8. Most licensed drugs share the same mechanism of action of targeting the viral polymerase and thus blocking DNA polymerization. Resistances to antiviral drugs have been observed for human cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus. A new terminase inhibitor, letermovir, recently proved effective against human cytomegalovirus. However, the letermovir has no significant activity against other herpesviruses. New antivirals targeting other replication steps, such as capsid maturation or DNA packaging, and inducing fewer adverse effects are therefore needed. Targeting capsid assembly or DNA packaging provides additional options for the development of new drugs.

1. Introduction

Human herpesviruses are large and structurally complex viruses divided into three subfamilies:

Alphaherpesvirinae such as herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and -2) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV);

Betaherpesvirinae such as human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and human herpesvirus types 6A, B and 7 (HHV-6A, -6B and -7); and

Gammaherpesvirinae such as EBV (Epstein–Barr virus) and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8). They are responsible for a wide variety of pathologies ranging from simple localized lesions to disseminated damages. The severity of the clinical forms and the extension of the lesions are closely linked to the immunosuppressive state of the patients. Alphaherpesviruses cause a variety of diseases ranging from cutaneo-mucosal vesicles to encephalitis or disseminated infections. Betaherpesvirus primary infections are often asymptomatic in immunocompetent patients, but viral reactivation can lead to life-threatening complications in immunocompromised individuals. For instance, HCMV is responsible for severe diseases in immunocompromised patients. Moreover, HCMV is the most common infectious cause of congenital malformations, with developmental delay, sensorineural hearing loss and fetal death in 10–15% of cases [

1]. Gammaherpesvirus primary infections are also often mildly symptomatic, except for infectious mononucleosis, but EBV can induce lymphoproliferative disorders, and HHV-8 Kaposi sarcoma.

The approved treatment for HSV-1 and HSV-2 infections is acyclovir. Ganciclovir, valganciclovir, cidofovir and foscarnet are used for the treatment of HCMV infections. These licensed molecules share the same mechanism of action of targeting the viral DNA polymerase. Limitations of these drugs are their dose-limiting toxicity and resistance emergence, leading to therapeutic challenges [

2,

3,

4]. Letermovir (AIC246) has recently been shown to be effective against HCMV infections. It is indicated for the prophylaxis of HCMV reactivation and HCMV disease in HCMV-positive adults receiving allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. However, this new drug has no significant activity against other herpesviruses or nonhuman CMV, and resistance mutations have already emerged [

5,

6]. Letermovir acts via a novel, not fully understood mechanism. This drug inhibits the cleavage of viral DNA concatemers and the formation of mature HCMV virions by targeting the pUL56 subunit of the viral terminase complex [

5,

6]. Mutations associated with letermovir resistance map mainly to pUL56. To date, no clinical treatment is available for EBV or HHV-6, -7 and -8.

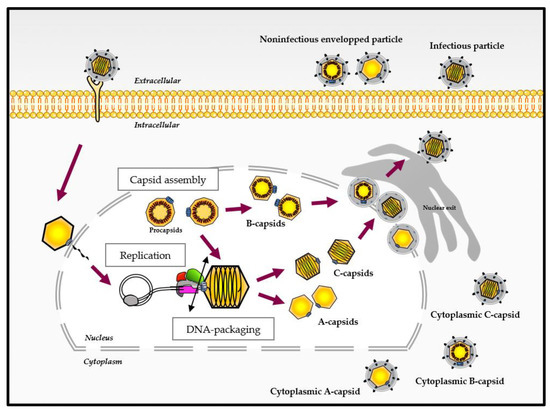

The infection cycle of HCMV, as for other Herpesviridae, comprises various steps in the cell nucleus where genome replication and the assembly of capsids take place. The replication of the 230 kbp DNA genome is thought to occur by a rolling circle process and results in the formation of concatemers that are cleaved into unit-length genomes and packaged into a preformed capsid (). The capsid assembly and DNA packaging are crucial steps for herpesvirus multiplication involving various viral proteins. Importantly, these steps are highly specific to the herpesvirus family, have no counterpart in the human organism and thus represent a target of choice for the development of new antivirals.

Figure 1. Different virus-like particles during the viral cycle of herpesviruses (adapted from [

5,

6]). After binding and entry into the host cell, the capsid is transported to the nuclear pore and delivers viral DNA into the nucleus. After genome replication, the DNA packaging step occurs and ends with the cleavage of the concatemers (represented by the double-ended black arrow), releasing viral DNA into the capsid. Different capsid forms are present in the host cell nucleus during infection. These capsid forms, referred to as A-, B- and C-capsids, represent empty capsids, scaffold-containing capsids and viral DNA-containing capsids, respectively. The C-capsids are considered as a precursor of infectious virus.

There remains an unmet need to develop new therapeutic strategies for herpesvirus infections targeting other replication steps than DNA replication and inducing fewer adverse effects. Addressing this issue, in this review, we will discuss recent findings on HCMV and herpesvirus capsid assembly and DNA packaging and further explain the potential of capsid and terminase proteins as new antiviral targets for the development of new effective treatments for HCMV infections.

2. Assembly of Herpesvirus Capsids

The capsid structure of herpesviruses was resolved by cryo-electron microscopy, which confirmed that the HCMV three-dimensional capsid structure is similar to the alpha- and gamma-herpesviruses’ capsid structure in overall organization [

7,

8]. The HCMV genome is twice the size of the VZV genome and >50% larger than the HSV-1 genome [

9]. Despite enclosing a much larger genome, the size of the HCMV capsid is similar to that of HSV-1 and to those of other herpesviruses, which range around a diameter of 100 nm [

10]. Infectious herpesvirus virions have an icosahedral capsid with a triangulation number (T) of 16, composed of 150 hexons that constitute the 30 edges and 20 faces of the icosahedron, with 11 pentons occupying 11 of 12 vertices and 320 triplexes that link the pentons and hexons together. Proteins forming an annular structure named the ‘portal’ occupy the twelfth vertex [

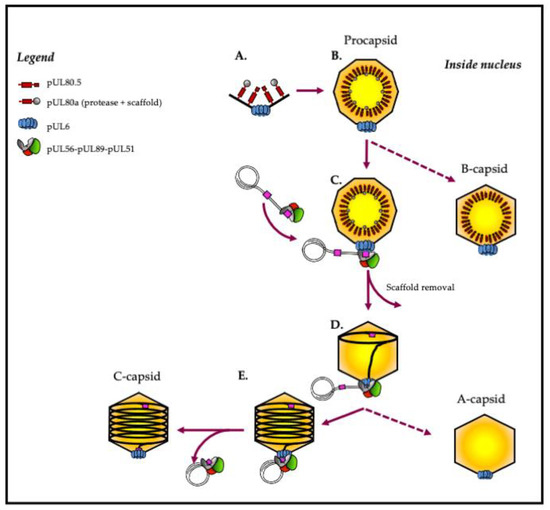

11]. The procapsid is a complex two-shell structure containing various proteins, including the major capsid protein (MCP) and the smallest capsid protein (SCP) (). Each protein is specifically designed to associate with the final structure in a precise manner [

11] ().

Figure 2. Capsid formation and DNA packaging of herpesviruses: model of HCMV. (A,B) The intranuclear capsid formation is initiated by the assembly of capsid proteins comprising MCP (black), SCP (black), triplexes (black), portal proteins (blue) and scaffold proteins (red and grey). (C) Maturation of the nucleocapsid is achieved by activating the maturational protease, which performs proteolytic digestion of the scaffold. At the same time, the terminase complex recognizes the “pac” motifs (“cis-acting packaging signal”) represented in pink. (D) The complex then performs an initial cleavage of viral DNA and exerts its ATPase activity to power the translocation of a unit-length DNA genome into the nucleocapsid. (E) Terminase proteins perform a second cleavage and release viral DNA into the capsid. Finally, the complex dissociates from the filled capsid and is ready for the next DNA-packaging step.

Table 1. Herpesvirus genes involved in capsid assembly and DNA packaging steps.

2.1. The Major Capsid Protein (MCP)

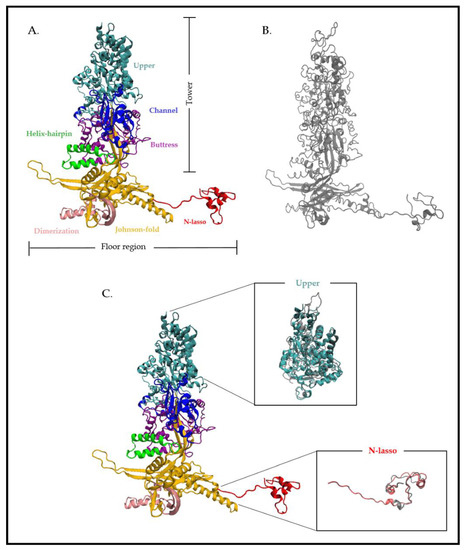

The most abundant protein components of the outer shell are the MCPs. Capsids comprise 11 pentons and 150 hexons that are divided into five and six MCP copies, respectively. In HCMV, the viral gene

UL86 encodes the major capsid protein pUL86, composed of 1370 amino acids (). pUL86 is essential for HCMV capsid formation and the generation of viral progeny. This is one of the most conserved proteins in herpesviruses [

12] (, ). The MCP domains are organized into two regions formed by distinct domains (): a tower region composed of the upper (amino acids (aa) 481 to 1031), channel (389 to 480 and 1322 to 1370), buttress (1107 to 1321) and helix-hairpin (190 to 233) domains, which make up the penton and hexon capsomer protrusions, and a floor region composed of the N-lasso (1 to 59), dimerization (291 to 362) and Johnson-fold (60 to 189, 234 to 290, 363 to 397 and 1032 to 1106) domains [

13]. Superposition of the cryo-electron microscopy structure of HCMV MPC (pUL86) and HSV-1 MCP (VP5) has shown strong similarities. Differences observed are more pronounced in the N-lasso and upper domain, in particular at the top of the upper domain where SCP binding occur (). This similarity of secondary and tertiary structures was also demonstrated through structural alignments based on the VP5ud model and the HCMV MCP model’s upper domain [

9]. For HHV-8, although the structures are similar, a loop in the HSV-1 MCP is replaced by a helix in HHV-8, producing a groove into which an SCP binds [

13].

Figure 3. Atomic structure of the HCMV major capsid protein (MCP) pUL86 and the HSV-1 MCP VP5. (A) Cryo-electron microscopy structure of the HCMV MCP pUL86 (each domain is highlighted in different colors). (B) Cryo-electron microscopy structure of the HSV-1 MCP VP5. (C) Partial superposition of the upper and N-lasso domain of pUL86 and VP5. Superposition of the proteins shows a higher atomic divergence for both the upper and N-lasso domains. The analysis is based on the HCMV and HSV-1 capsid structure (PDB: 5VKU and 6CGR) using Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD 1.9.3).

2.2. The Smallest Capsid Protein (SCP)

The

UL48.5 gene encodes the smallest HCMV protein. This protein of 75 amino acids, essential for HCMV viral growth, would participate in the cohesion of the capsid by coating the ends of the hexons and pentons [

14]. Unlike in HCMV, where SCPs bind hexons and pentons so that exactly one SCP binds each MCP, the HSV-1 SCP binds only hexon MCPs [

9,

15]. Moreover, the SCP in HSV-1 is nonessential for viral growth in cell culture [

16].

2.3. External Scaffolding Proteins: Triplex Proteins

The triplexes sit atop the MCP N-lasso triangle and are critical for capsid morphogenesis, most likely linking pentons and hexons together, directing assembly and stabilizing the structure prior to maturation. There are 320 of them in the capsid. Triplexes are heterotrimers consisting of two dimer-forming parts of the minor capsid protein (mCP), coupled with a single copy of the minor capsid binding protein (mCP-bp) [

14]. The mCP of HCMV, pUL85, is a protein composed of 306 amino acids that forms dimers [

9] (). The HCMV mCP-bp is encoded by the

UL46 gene ().

2.4. Maturational Protease and Internal Scaffolding Protein from the Fusion Protein

In addition to the structural proteins, capsid assembly involves the formation of scaffold proteins for the generation of the capsid subunit and the procapsid structures. The scaffolding proteins of HCMV have been identified as gene products of the

UL80a and

UL80.5 open reading frames (ORFs) [

17].

UL80a encodes the assembly protein precursor, which is proteolytically processed into protease and scaffold domains. The scaffold domain corresponds to the C-terminus (C-term; pUL80, aa 336 to 708) and the protease (also called assemblin, pUL80a) to the N-terminus (N-term; pUL80, aa 1 to 256). The protease is subsequently autocatalytically cleaved into two more peptides [

17]. Three homologs are reported in HSV-1, VP21 (pUL26), VP24 (pUL26) and VP22a (pUL26.5) [

18] (). The assembly protein, encoded by

UL80.5, directly interacts with the MCP (pUL86) [

19]. Importantly, the MCP–assembly protein interaction is essential for the nuclear translocation of the MCP [

20]. A conserved domain in the N-term of pUL80.5 promotes self-interaction and has been suggested to lead to the generation of multimers [

20]. The self-interactions together with the MCP is thought to catalyze the formation of intranuclear hexons and pentons [

21]. The HSV-1 homolog

UL26.5 encodes preVP22A, which interacts with the HSV-1 MCP (VP5) through its C-term 25 amino acids that remain inside A-, B- and C-capsids [

22]. Specifically, 12 hydrophobic amino acids at this C-term end are critical for the interaction, suggesting that the preVP22A–VP5 interaction is a hydrophobic interaction [

22].

Although the scaffold plays a central role in capsid assembly, to date, no scaffolding protein has been found within the mature capsid or the virion ().

UL80a encodes the assembly protein precursor composed of the protease (pUL80a) and the assembly protein (pUL80.5). Like HCMV, the HSV-1 pUL26 is initially extended at its N-term by the protease, and a linker and its C-term part is identical to the major form, pUL26.5 [

23]. This fusion provides a convenient mechanism for incorporating the protease into the assembling procapsid. The final step of the capsid maturation in HCMV and HSV-1 involvs a proteolytic cleavage for the MCP binding domain of pUL80.5 and preVP22a, respectively [

24,

25]. Bioinformatics analysis has identified a protein family predicted to share the canonical herpesvirus protease fold, having conserved Ser and His residues in their active sites [

23].

2.5. The Portal Protein

The capsid is also composed of a portal that occupies one of the 12 vertices of the capsid and plays a critical role for herpesvirus replication. This arrangement of 12 monomers forms a ring, allowing herpesvirus DNA to be incorporated into the preformed capsid. Portal proteins act as the docking site for the terminase–DNA complex. pUL104 is the HCMV dodecameric portal protein, with 12-fold symmetry. pUL104 directly interacts with the large terminase subunit pUL56. This interaction was shown to be essential for DNA insertion into the capsid [

26]. pUL6, the HSV-1 portal protein, is one of the most studied portal proteins in herpesviruses, and its structure was recently resolved using cryo-electron microscopy [

27]. Structurally, a portal monomer consists of five domains; the wing, stem, clip, β-hairpin and wall [

27]. The twelve monomers are arranged such that their loop-rich wing domains form the outer periphery of the complex. The remaining stem, clip, β-hairpin and wall domains line the interior of the portal’s DNA translocation channel. The formation of a stable ring requires a putative leucine zipper, as well as disulfide bonding between subunits [

28,

29]. It has been shown that the portal protein pUL6 interacts with the scaffolding protein VP22a. This interaction requires a region corresponding to amino acids 143 to 151 of VP22a and is essential for viral replication, DNA cleavage/packaging and incorporation of the portal into capsids [

11].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/life11020150