2. Daisy Tree Diversity in Mexico and Comparison with Other Diverse Areas

The study by Beech et al. [

25] reported 3364 tree species for Mexico, positioning this country in the top 10 of the most tree species-rich countries, and due to our efforts in listing additional tree species since then, this has been increased to 3522 species [

33]. Similarly, for native Mexican Asteraceae trees, in contrast to the previous studies and reports, we report a much higher number of arborescent Asteraceae taxa. Asteraceae is a main component of vegetation and bioregions along the Americas, with Mexico standing out as the most species-rich country for this family at a global level [

1,

2].

With respect to the tree species richness of Asteraceae in megadiverse countries and areas, Mexico and Central America rank second in the number of genera and species with 45 and 149, respectively. The first corresponds to Colombia as it is home to 169 species [

7], followed by Brazil with 38 genera [

34], and Ecuador, with 14 genera and 55 species, all of them in some risk category according to the IUCN Red List criteria [

8]. Considering regional scales, the Amazonian (an area that includes the territory of nine South American countries: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guyana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela) is an area of high diversity with 37 genera and 107 species [

35]. With respect to the number of Asteraceae trees registered in the flora of North America [

4], eight genera and 10 species were found, of which five are mainly shared with the northern part of Mexico; hence, the high diversity of daisy trees in the country stands out. A similar situation occurs with the flora of China [

6]; in this case, the numbers are even more contrasting, since in that area only five genera and nine species of native trees are registered. In addition, in China there are also two genera and three cultivated species that are native to Mexico or Central America and that have become naturalized in Chinese territory. These are the only daisy tree species shared between Mexico, Central America, and that region in Asia.

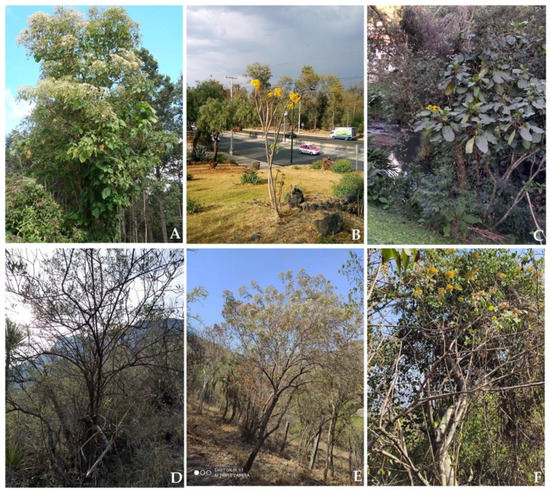

Tree-like Asteraceae are generally not prominently visible in the forests where they occur, as they grow in the understory or in open places, whereas they can reach up to 20 m in cloud forest, but they do not form a prominent part of the forest structure. In contrast, in scrubland vegetation and semi-evergreen low forest, they may be dominant, and an important part of the structure of the forest. It has been documented that Mexican coniferous forests show a relationship between forest structure and tree diversity [

36]. In the particular case of Asteraceae, the highest number of arborescent species is found in pine forests (71.8%), while

Abies forests concentrate just over 11% of the 149 species present in the country. Even considering that one and the same species can be found in various vegetation types, the percentages for pine and

Abies forests are considerable.

3. Uses of Mexican Daisy Trees

A considerable amount of ruderal or malezoid Asteraceae are nectariferous and therefore are particularly important for honey-producing bees [

37,

38,

39,

40], or other pollinators, which are also attracted in addition to nectar, by the yellow colour of the flowers of many species [

41]; hence, they do not depend on a single vector that carries out cross-pollination. The nectar produced by the Asteraceae is rich in glucose, fructose and sucrose [

42], which encourages various groups of insects, including Hymenoptera, Diptera, Lepidoptera, and Coleoptera, to obtain food and assist in the pollination of these species [

42,

43,

44]. Even several groups within Mutisieae are hummingbird-pollinated [

45,

46]. The family is of high economic importance as a honey supplier in several regions in Mexico. The worldwide known migratory phenomenon of the monarch butterfly occurs every year during the fall when millions of butterflies travel from the south of Canada and the north of the United States of America to Mexico to spend the winter season in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, located on the limits of Michoacán and the State of Mexico [

47]. The presence of 103 Asteraceae species has been documented in its core zone [

48]. From the illustrated flora of the Reserve [

49], it can be observed that the butterflies feed on practically all Asteraceae that grow in the area.

Asteraceae are also an important source of food for honey-producing bees in Mexico, both European and native [

37,

38,

40]. Among the species most used by these insects, there is a significant percentage of those that have been classified as “weeds” [

40]. Indirectly, these plants are a source of income for beekeepers around the world. Mexico is among the top 10 honey producers worldwide, ranking fourth in exports of this product. In 2019 alone, 61.9 million tons of honey were produced, thus achieving an increase of just over six percent compared to the previous five-year period [

50]. Eight states account for 70% of the national production, with Yucatán, Campeche, Jalisco, and Chiapas as the main producers [

51].

Asteraceae are used in traditional medicine to treat various conditions such as the treatment of stomach and respiratory diseases, since around 6000 species contain sesquiterpene lactones, chemical compounds with antimicrobial, antiprotozoal, anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic properties [

44,

52,

53]. Others are used as food, whether they are cultivated to obtain leaves or meristems, roots, tubers, heads, seeds to produce oil, natural dyes, bio-insecticides, or as ornamental or florist plants [

52]. Although only eight Mexican daisy tree species are used for ornamental purposes, it is important to highlight the potential that other species of the family could have, since, considering their importance as species that produce nectar and pollen, they would be helpful in reducing the loss of bees and other pollinator groups.

The dahlia deserves a special mention as it has been the national flower of Mexico since 1963 [

54], since the country has the largest number of wild and endemic species, with 38 and 35, respectively. These are a source of germplasm for the more than 50,000 varieties grown around the world [

55]. In addition to the dahlia, there are other wild species with ornamental potential due to their visible inflorescences, among which the following stand out:

Montanoa bipinnatifida and

Bartlettina sordida. The first is highly appreciated in Mexico [

56,

57], Spain [

58], Australia [

59], and New Zealand [

60], and the second in Spain [

61]. Although there are no published data, some shrub or tree species of Asteraceae are used as living fences, in seasonal crops such as corn or beans, or in vegetables or gardens, among which the following stand out:

Barkleyanthus salicifolius,

Baccharis heterophylla,

Baccharis salicifolia,

Montanoa tomentosa,

M. leucantha, and

M. grandiflora. Asteraceae species associated with corn (milpa) are mainly

Tithonia tubiformis,

Cosmos bipinnatus,

C. sulphureus,

Bidens odorata,

B. pilosa,

Melampodium perfoliatum,

Simsia amplexicaulis, and

Viguiera dentata, weedy plants that farmers allow to grow alongside the milpa to serve as crop protection, as the loss of the harvest is lessened in the case of a grasshopper or locust plague [

29] (pers. obs.).

5. Conservation

The occurrence points of the known records, as well as the potential distribution models of Asteraceae trees compared with the areas occupied by the main natural protected areas present in the country, show a tendency to reduce their presence in some areas that are currently particularly rich in species; however, in other zones they will remain or increase; some of these correspond to protected natural areas.

Mexico has 182 protected natural areas distributed in maritime and continental territory. Of these, 67 correspond to National Parks, 44 are Biosphere Reserves, 40 Flora and Fauna Protection Areas, 18 Sanctuaries, eight Natural Resources Protection Areas, and five Natural Monuments [

66]. Those that are located in continental territory are equivalent to 10.88% of the country’s land surface [

66]. One of the terrestrial protected areas with the largest territorial extension is the Flora and Fauna Protection Area Cuenca Alimentadora del Distrito Nacional de Riego 043, Estado de Nayarit, located in the west of the country, comprising part of the territory of the states of Aguascalientes, Jalisco, Durango, Nayarit, and Zacatecas [

66]. It is home to around 11 types of vegetation, more than 2000 species of vascular plants and at least two endemic daisy tree species [

67,

68]. The territorial extension and biological diversity of this protected area is considerable. In the particular case of Asteraceae trees, the climatic suitability models estimate that the diversity of species will remain in the western part of the country, a situation similar to what could occur in the Sierra de Manantlán, one of the most important biosphere reserves in the western region with an area of 139,577.12 ha [

66]. The latter was recognized as a biosphere reserve for the biological diversity that it houses in its territory, which includes vegetation of dry, temperate, and humid environments, in addition to being the main water source for more than 430,000 inhabitants of southern Jalisco and northern Colima [

69].

The biosphere reserves are distributed throughout the country; 70% have territorial extensions of more than 100 ha or a high species diversity [

66]. In the center of the country, the Sierra Gorda stands out with an extension of 383,567.45 ha, located on the limits of Querétaro, Guanajuato, San Luis Potosí and Hidalgo, and Sierra Gorda de Guanajuato (236,882.76 ha) [

66], which together occupy the seventh place in size of all the protected natural areas of Mexico [

70]. In its territory, there are dry shrublands and temperate forests, which host a great diversity of plants, many of them endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental [

70]. This region has three hydrological sub-basins and a dam declared a Ramsar site, as it is a wetland of global importance [

70]. The climate suitability models estimate a slight decrease in the number of tree species of Asteraceae (). Among those that would be affected are

Baccharis heterophylla,

Barkleyanthus salicifolius,

Critonia morifolia,

Koanophyllon albicaulis, and

Nahuatlea hypoleuca, species that fortunately are not restricted to Mexico, since the first four also occur in Central America and the fifth in the south of the United States of America.

One of the most important protected areas in central Mexico is the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve with an area of 56,259.05 ha [

66]. In its territory, there are pine forests,

Abies forests, and oak forests that contribute in an important way to the carbon capture from industrial areas and favour the recharge of aquifers that provide water to the metropolitan area of Mexico City, as well as various areas of the states of Michoacán and Mexico [

47]. Our models estimate that the daisy tree diversity in this region will be maintained in the next century, if this also happens with the ecosystems where they are found, as well as with the environmental services that they provide to this area of the country.

The Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley Biosphere Reserve, with a surface area of 490,186.87 ha, is the largest of all those found in arid and semi-arid zones [

66]. In this case, the climatic suitability models estimate a possible decline in species (, and ). Although the number of trees that are currently in its territory is minimal, several species dominate and give structure to the vegetation of some areas, among them:

Baccharis heterophylla,

Montanoa leucantha,

M. tomentosa,

Nahuatlea hypoleuca,

N. smithii,

Parthenium tomentosum,

Pittocaulon praecox,

P. velatum,

Roldana eriophylla, and

R. oaxacana. Of these,

Nahuatlea smithii and

Roldana eriophylla are practically endemic to this region and could be at risk if the scenario predicted by the models takes place.

In the case of tropical ecosystems and particularly rainforests, the main biosphere reserves are: Montes Azules (331,200 ha) and El Triunfo (119,177.29 ha) in Chiapas, and Los Tuxtlas (155,122.47 ha), in Veracruz [

66]. Interestingly, the three are in territory belonging to Pleistocene refugia; Montes Azules corresponds to the refugium called Lacandonia and El Triunfo to Soconusco [

62]. Both are considered primary Pleistocene refugia; i.e., these zones maintained constant temperature and precipitation conditions during the dry and cold periods that occurred during this period, which allowed them to safeguard common species in humid tropical forests [

62]. The climate suitability models estimate different situations in the event of abrupt climatic events, since a probable reduction would occur in Montes Azules, while in El Triunfo, the Asteraceae tree populations would remain. This may be due to the climatic conditions that currently prevail in each of these regions, since in Montes Azules the current oscillation of temperature and precipitation is lower (average annual temperature between 22 and 24 °C; average annual precipitation 2000 to 3000 mm [

71]), compared to the values recorded in El Triunfo (mean annual temperature of 18 to 22 °C, with a mean annual rainfall of 1000 to 3000 mm [

72]). However, both sites have invaluable biological potential and value. Montes Azules protects 20% of the plant species present in Mexico; recent calculations indicate that one hectare of this reserve protects about 160 tree species and about 700 vascular plants [

73]. In El Triunfo, there are important extensions of mountain cloud forest, considered one of the ecosystems that hosts the greatest diversity of trees in North and Central America [

74]. The Los Tuxtlas reserve is located in an area recognized as a secondary Pleistocene refugium, because it corresponds to an area that only managed to preserve itself from the drastic drop in temperature or precipitation, during the alternation of cold and dry periods of the Pleistocene [

62].

Los Tuxtlas homes coniferous forest, oak forest, mountain cloud forest, high evergreen forest, and mangroves, where around 3000 plant species have been documented, and it is also one of the five areas with the highest amount of tree endemism in Mexico [

75]. For this site, the climatic suitability models estimate a decrease in the number of daisy trees. Considering the importance of Los Tuxtlas as an area of endemism for tree species, it would be interesting to explore what happens with other angiosperm groups. In this area, the average annual temperature ranges between 22 and 26 °C and rainfall varies from 1500 to 4500 mm [

76]. Although the temperature is relatively constant, the precipitation has a considerable range of variation, which would support the proposal that it was a secondary Pleistocene refugium [

62].

Apparently, the aforementioned biosphere reserves will allow that, given a scenario such as that estimated by our models, the probable reduction of the populations does not become catastrophic as in other areas of the country, which are particularly rich in diversity and Asteraceae endemisms, as occurs with the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley.

Anthropocene refugia correspond to territories that meet the following qualities: being ecologically suitable areas to house the diversity units analyzed and having relatively low levels of observed and predicted anthropogenic pressure to allow their long-term persistence in this area, i.e., through several generations [

77]. The main difference between Pleistocene and Anthropocene refugia is that the former are sites where organisms resisted and responded to glacial and interglacial oscillations of the late Quaternary, having the possibility of expanding their distribution once environmental stress conditions decreased [

78]. In contrast, in order to characterize probable refugia from the Anthropocene, climate change derived from anthropogenic pressures is taken into account [

77]. Therefore, the identification of Anthropocene refugia is useful to categorize, plan, and decide where to establish conservation areas for the group of interest [

77].

In the case of daisy trees, the models allow the identification of some areas that meet sufficient characteristics to be considered Anthropocene refugia and, therefore, to be maintained or proposed as conservation areas, although some of them are already cataloged like this. This is the case of the western region of Jalisco where the Flora and Fauna Protection Zone Cuenca Alimentadora del Distrito Nacional de Riego 043, Estado de Nayarit and the Biosphere Reserve Sierra de Manantlán are located. Moreover, the Biosphere Reserves of the Monarch Butterfly, on the limits of Michoacán and the State of Mexico, and of the Tacaná Volcano and El Triunfo in Chiapas are also already existing conservation areas; the latter has previously been proposed as a Pleistocene refugium [

62]. Based on the results obtained, other areas that could function as Anthropocene refugia correspond to the northern portion of Michoacán and southern part of the State of Mexico, which together with western Jalisco form part of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, an area that currently contains a high richness of Asteraceae trees, which, according to our models, is estimated to remain or increase (, and ). The mountainous regions of Guerrero and Oaxaca, corresponding to the Sierra Madre del Sur (), also seem to meet the characteristics of Anthropocene refugia. Although there are currently no natural protected areas decreed in these areas, despite being sites with high biological diversity and a large number of endemisms, it is a fact that their geographical location and the difficulty of accessing them has kept them safe from human damage. Special mention should be made of the Sierra Norte de Oaxaca, an area particularly rich in diversity and endemism of Asteraceae [

79], in which the models indicate that there are also adequate conditions to serve as an Anthropocene refugium, which is confirmed by the fact that it has also been considered as a secondary Pleistocene refugium [

62]. However, unlike the mountainous region of central Oaxaca, the Sierra Norte has sufficient infrastructure to access its territory and forest management of the coniferous forests, although the other ecosystems remain almost intact. This shows that, despite the fact that this area is not recognized as a protected area at the federal level, the community forest management that the inhabitants of the region have carried out has been adequate and successful, since in addition to generating jobs and resources for the inhabitants of the region, the forest area has increased in the last four decades [

80,

81,

82,

83].

Based on the aforementioned, the sites identified as priority areas to conserve the diversity and endemism of daisy trees are the following: Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (including Protected Areas of western of Jalisco), Sierra Madre del Sur, Sierra Norte de Oaxaca, El Triunfo and Tacaná Volcano. All these regions have previously been identified as diversity hotspots of other groups of plants [

84,

85] and animals [

86].

As a consequence, whether the efforts and proposals to conserve nature are federal or local, everything seems to indicate that the establishment, maintenance and conservation of protected natural areas that currently exist in Mexico have been adequate. However, the ideal would be to keep them intact in the long term or, as far as possible, to extend their territory in order to safeguard a greater number of species, both Asteraceae and other families of angiosperms.

In conclusion, relatively few Mexican daisy tree species are currently seriously threatened by climate change or other factors, as most species are widely distributed. Direct exploitation for human use is also not generally a threatening factor. Mexico ranks first at the global level with respect to daisy diversity and second with respect to daisy tree diversity. As mentioned above, Asteraceae are ecologically successful, and the same goes for tree-like representatives of this family. However, it will be important to include those endemic species whose IUCN Red List assessment indicates that they are endangered or critically endangered in the NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, as several of these, e.g., Ageratina chimalapana, Lepidonia wendtiana, Mixtecalia teitaensis, Montanoa revealii, and Verbesina sousae, occur in areas subject to anthropogenic pressures that puts their survival at risk, either due to changes in land use, excessive or unplanned tourism, and the extraction of stone material.