Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Agronomy

One of the major health risks for humans, especially for those living in large cities, is air pollution. Air pollution consists mainly of emissions of particulate matter (PM), nitrogen oxides, sulphur dioxide, ammonia and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). The organic carbon fraction of particulate matter is a mixture of hundreds of organic compounds, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), or polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs), some of which are mutagenic and/or carcinogenic. Because this particulate matter represents a serious threat for human health, measures to reduce emissions and to eliminate contaminants need to be strongly reinforced, with a focus on novel biotechnologies.

- atmospheric pollutants

- plant-bacteria interactions

- rhizoremediation

- phylloremediation

- “Green Architecture”

1. Introduction

The number of megacities (those with more than 10 million inhabitants) is predicted to increase from 33 to 43 by 2030 (https://population.un.org/wup/ (accessed on 3 March 2021). One of the major negative impacts for citizens living in large cities is air pollution. By 2030 it is estimated that total premature deaths due to air pollution will reach 3.1 million annually (OECD Environment Outlook to 2030).The management of urban growth in the context of sustainable development must, therefore, maximize the benefits of agglomeration whilst minimizing the potential adverse impacts.

The major source of air pollution in big cities is the combustion of fossil oil derivatives, although biomass burning, or industrial exhaust, among others, road dust are also important sources of contamination[1]. Air pollution consists mainly of emissions of particulate matter (PM), nitrogen oxides, sulphur dioxide (SO2), ammonia (NH3) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) [2]. PMs are complex mixtures in which organic carbon (OC) is abundant [3]. OC and VOCs contain compounds such a BTEXs (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes), PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) and polychlorinated dibenzo–p–dioxins and dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs), that are mutagenic and/or carcinogenic [4][5]. Removal of some of these atmospheric toxic compounds through associations between plants and bacteria, in the context of Green Architecture, is discussed in this work.

2. Origin,Toxicity and Bacterial Degradation of BTEX, PAHs, PCBs and Dioxins

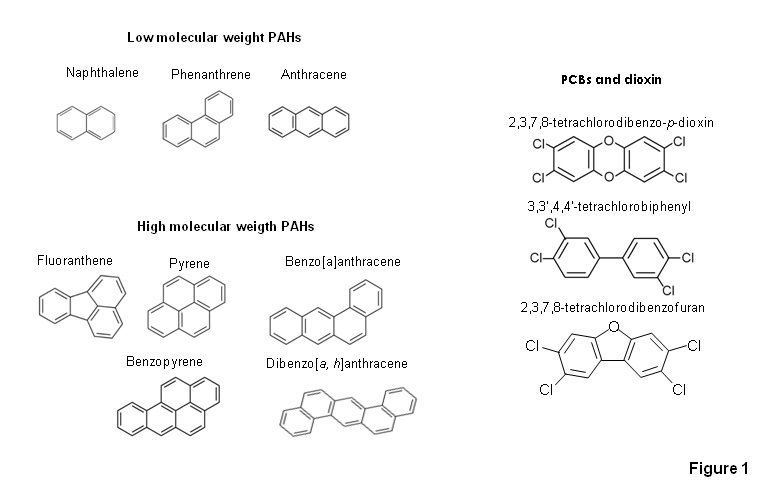

Among the most abundant contaminants in air pollution are BTEX, PAHs, PCBs and dioxins (Fig. 1). BTEX and PAHs are petroleum-derived compounds that are released into the atmosphere as emissions from combustion of fossil fuel derivatives, volcanic eruptions or forest fires, amongst others [6][7]. Many of them are considered carcinogenic and mutagenic[4][5]. PCBs, although banned in 1978 in the US and later on in many other countries, were produced in huge amounts as insulators and dielectric or coolant fluids for cables, electrical apparatus and heat transfer systems [8]. Chlorinated dioxins are generated as unwanted by-products in the chemical syntheses of several pesticides, disinfectants, wood preservatives and in the incineration of PCB-containing plastic insulators [9]. Both chlorodioxins and co-planar PCBs cause immunotoxic and endocrine effects, as well as the induction of malign tumours, neurotoxic and/or immunotoxic effects [4].

Figure 1. Chemical structures of different polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dioxin and dioxin-like molecules;

The toxicity of PAHs, PCBs and chlorodioxins for animals and humans is based on their capacity to bind to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), which leads to the transcription of target genes, among them, the genes of the cytochrome P450-monooxygenases (CYP) [10][11].

Biodegradation of BTEX and PAHs is performed by a large number of different microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and algae [12][13]. Aerobic bacterial biodegradation of these compounds requires the presence of O2 to initiate the enzymatic attack on the aromatic rings of PAHs by a dioxygenase that catalyses the dihydroxylation of PAHs. These dihydroxylated intermediates are then cleaved by ring-cleaving dioxygenases, leading to different compounds that are further converted to tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates, used for anabolic biomass formation and mineralized to CO2 [14]. Only a single specialized bacterium, Sphingomonas wittichii strain RW1, can use the non-chlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin as its sole carbon- and energy source and co-metabolize several of its chlorinated derivatives [15]. Other bacterial isolates, with highly similar catabolic genes to that of the S. wittichii strain RW1 are capable of growing using PCBs as the sole carbon source [16].

3. Deposition, transport and detoxification of contaminants in plants

Atmospheric contaminants can be deposited directly from the air onto leaves or in soils, and are then adsorbed to roots [17]; they can also be mobilized from soil to leaves by evaporation or wind, or be transported from roots to leaves [18]. The amount of contaminants which finally accumulates in vegetation depends on the physico-chemical properties of the particular contaminant, and also on the characteristics of leaf surfaces and root architecture, as well as on many other environment-related parameters such as wind, rain, temperature, sorption to soils, organic content of soils, and composition of root exudates [19].

After deposition, it is accepted that mobilization of contaminants through the plant is a consequence of two different processes: i) the accumulation of contaminants in plant tissues mainly correlated to their hydrophobicity and plant lipid contents, and ii) the transfer between plant tissues driven mainly via xylema [20]. Once located in the plant interior, contaminants are mainly activated by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYP). The resulting compounds are later conjugated with glucose, glucuronic acid, or glutathione moieties. These conjugates are then sequestered in the cell wall or in vacuoles [21].

Despite evidence for the accumulation and subsequent biotransformation of organic contaminants in plants, it is believed that the contribution of plant uptake for their removal from the environment is very low. Soil-bound contaminants, such as PAHs, are strongly associated with soil organic matter and poorly transferred to plant roots. Furthermore, contaminants or derived products accumulating in plant cell walls or vacuoles may return to the environment after plant decay. However, plants may stimulate organic contaminant degradation through several processes such as by increasing the bioavailability of the contaminants, influencing desorption from soil particles, and stimulating the biodegrading microbiota in the rhizosphere [22][23].

4. Plant-Bacteria Associations for the Elimination of Atmospheric Contaminants

Whilst bacteria are armoured with a battery of degradative genes encoding catabolic biocatalysts, plants offer a large surface area to collect air particles, and they are able to stimulate bacterial activities in their rhizosphere [24]. Therefore, the combination of both organisms could be a good solution for the elimination of contaminants [25]. Two different strategies can be used:

4.1. Rhizoremediation

This consists in the elimination of contaminants from the soil surrounding the plant root, and it is based on the nutritional effect of plant roots (that secrete different metabolites that microbes can use as a nitrogen, carbon, sulphur, or phosphorus source); and in the capacity of root exudates to improve the bioavailability of contaminants. Plant roots provide a large surface area on which microorganisms can proliferate and reach high cell densities. There are two crucial aspects for a successful rhizoremediation: i) the pathways for the degradation of contaminants have to be operative and free of catabolite repression effects [26], and ii) the contaminant has to be bioavailable in a form that it can be taken up by the bacterial cell [27]. The elimination of contaminants by bacteria decreases their concentration in the rhizosphere and, therefore, improves plant growth [28].

4.2. Phylloremediation:

The phyllosphere, the surface area of plant leaves and stems, can be 6-14 times greater than the land where the vegetation is growing upon [29]; therefore, it is an important environment for the elimination of atmospheric contaminants. The accumulation of air pollutants and airborne PMs on leaf surfaces is dependent on the plant species, leaf size and structure, but is also affected by the types of waxes which make up the cuticle, the hairs covering the leaf, and leaf smoothness [19][30]. Although this environment is a hostile habitat for microorganisms (exposition at high doses of UV radiation, temperature variations, climatic factors, low nutrient content and pollution [31], it can support bacterial populations of up to 108 bacteria g−1 leaf together with smaller fungal populations [32]. It has been demonstrated that natural populations of phyllospheric bacteria can remove hydrocarbon-related air pollutants [33]; in some cases this capacity was improved by spraying bacteria able to degrade the pollutants [34].

5. Removal of air pollutants in the context of Green Architecture

Green Architecture involves the construction of eco-friendly buildings and infrastructures to minimize the harmful effects of urbanization on the environment, including outdoor and indoor air pollution. According to these practices, elements traditionally used for aesthetic reasons are now ecological methods for sustainable edification [35]. Some architectural elements to mitigate air pollution are already being developed such as green wall biofilters in buildings, or green belts established around industrial areas [36][37]. In these elements, plants are normally considered passive accumulators of contaminants. However, improving rhizosphere and phyllosphere bacterial communities in these architectural elements with tailor-made bacterial consortia, which attack diverse organic contaminants, could be considered a way of improving the capacity of plants to remove air pollutants [25].

In order to successfully implement the utilization of plant-bacteria combinations as a strategy to ameliorate air pollution in cities, there are still a number of issues that need to be solved: i) Selection of the best bacterial consortia, using endophytic, phyllospheric and/or rhizospheric bacteria, taking into consideration all environmental requirements; ii) because of the close proximity of green structures to citizens, detailed safety analyses of degrading microorganisms and studies about the accumulation of possible toxic intermediates from degradative pathways should be investigated [38][39]; and iii) the plant and its associated microbiome have co-evolved throughout time, establishing complex interrelationships to function almost as a single supra-organism (holobiont) [40]. During bioremediation, the presence of pollutants and exogenous bacteria can affect the functioning of the holobiont [41]. The study of these new interactions and how the degradation potential of contaminants could be altered by the complex signalization existing in these niches is a novel research field to be explored.

6. Conclusions

The successful utilization of plant-bacteria combinations in Green Architecture is a promising technology that will have clear economic implications, less public expenditure in the citizens’ healthcare and lower the costs of contamination control.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/agronomy11030493

References

- Daniela Dias; Jorge Humberto Amorim; Elisa Sá; Carlos Borrego; Tânia Fontes; Paulo Fernandes; Sérgio Ramos Pereira; Jorge Bandeira; Margarida C. Coelho; Oxana Tchepel; et al. Assessing the importance of transportation activity data for urban emission inventories. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2018, 62, 27-35, 10.1016/j.trd.2018.01.027.

- Nicholas Z. Muller; Robert Mendelsohn; Measuring the damages of air pollution in the United States. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 2007, 54, 1-14, 10.1016/j.jeem.2006.12.002.

- Barbara J. Turpin; Peer Reviewed: Options for Characterizing Organic Particulate Matter. Environmental Science & Technology 1999, 33, 76A-79A, 10.1021/es992683s.

- Chenglu Bi; Yantong Chen; Zhuzi Zhao; Qing Li; Quanfa Zhou; Zhaolian Ye; Xinlei Ge; Characteristics, sources and health risks of toxic species (PCDD/Fs, PAHs and heavy metals) in PM2.5 during fall and winter in an industrial area. Chemosphere 2020, 238, 124620, 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124620.

- Siti Amira ‘Ainaa’ Idris; Marlia M. Hanafiah; Firoz Khan; Haris Hafizal Abd Hamid; Indoor generated PM2.5 compositions and volatile organic compounds: Potential sources and health risk implications. Chemosphere 2020, 255, 126932, 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126932.

- Alexei Remizovschi; Rahela Carpa; Ferenc L. Forray; Cecilia Chiriac; Carmen-Andreea Roba; Simion Beldean-Galea; Adrian-Ștefan Andrei; Edina Szekeres; Andreea Baricz; Iulia Lupan; et al. Mud volcanoes and the presence of PAHs. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 1-9, 10.1038/s41598-020-58282-2.

- Wei Ting Hsu; Mei Chen Liu; Pao Chen Hung; Shu Hao Chang; Moo Been Chang; PAH emissions from coal combustion and waste incineration. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2016, 318, 32-40, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.06.038.

- Brenda Eskenazi; Marcella Warner; Paolo Brambilla; Stefano Signorini; Jennifer Ames; Paolo Mocarelli; The Seveso accident: A look at 40 years of health research and beyond. Environment International 2018, 121, 71-84, 10.1016/j.envint.2018.08.051.

- Katrin Vorkamp; An overlooked environmental issue? A review of the inadvertent formation of PCB-11 and other PCB congeners and their occurrence in consumer products and in the environment. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 541, 1463-1476, 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.10.019.

- Lucie Larigot; Ludmila Juricek; Julien Dairou; Xavier Coumoul; AhR signaling pathways and regulatory functions. Biochimie Open 2018, 7, 1-9, 10.1016/j.biopen.2018.05.001.

- Nishad Jayasundara; Lindsey Van Tiem Garner; Joel N. Meyer; Kyle N. Erwin; Richard T. Di Giulio; AHR2-Mediated Transcriptomic Responses Underlying the Synergistic Cardiac Developmental Toxicity of PAHs. Toxicological Sciences 2014, 143, 469-481, 10.1093/toxsci/kfu245.

- Sunita J. Varjani; Microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons. Bioresource Technology 2017, 223, 277-286, 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.10.037.

- Debajyoti Ghosal; Shreya Ghosh; Tapan K. Dutta; Youngho Ahn; Current State of Knowledge in Microbial Degradation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs): A Review. Frontiers in Microbiology 2016, 7, 1369, 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01369.

- Robert A. Kanaly; Shigeaki Harayama; Advances in the field of high-molecular-weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon biodegradation by bacteria. Microbial Biotechnology 2009, 3, 136-164, 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2009.00130.x.

- R M Wittich, H Wilkes, V Sinnwell, W Francke, P Fortnagel; Metabolism of dibenzo-p-dioxin by Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1.. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1992, 58, 1005-1010, .

- Salametu Saibu; Sunday A. Adebusoye; Ganiyu O. Oyetibo; Debora F. Rodrigues; Aerobic degradation of dichlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin and dichlorinated dibenzofuran by bacteria strains obtained from tropical contaminated soil. Biogeochemistry 2020, 31, 123-137, 10.1007/s10532-020-09898-8.

- Venkata L. Reddy Pullagurala; Swati Rawat; Ishaq O. Adisa; Jose A. Hernandez-Viezcas; Jose R. Peralta-Videa; Jorge L. Gardea-Torresdey; Plant uptake and translocation of contaminants of emerging concern in soil. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 636, 1585-1596, 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.375.

- Chris D. Collins; Eilis Finnegan; Modeling the Plant Uptake of Organic Chemicals, Including the Soil−Air−Plant Pathway. Environmental Science & Technology 2010, 44, 998-1003, 10.1021/es901941z.

- Shaojian Huang; Chunhao Dai; Yaoyu Zhou; Hui Peng; Kexin Yi; Pufeng Qin; Si Luo; Xiaoshan Zhang; Comparisons of three plant species in accumulating polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from the atmosphere: a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2018, 25, 16548-16566, 10.1007/s11356-018-2167-z.

- Fuxing Kang; Dongsheng Chen; Yanzheng Gao; Yi Zhang; Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in subcellular root tissues of ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.). BMC Plant Biology 2010, 10, 210-210, 10.1186/1471-2229-10-210.

- Elizabeth Pilon-Smits; PHYTOREMEDIATION. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2005, 56, 15-39, 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144214.

- Jiaolong Wang; Xiaoyong Chen; Wende Yan; Chen Ning; Timothy Gsell; Both artificial root exudates and natural Koelreuteria paniculata exudates modify bacterial community structure and enhance phenanthrene biodegradation in contaminated soils. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 128041, 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128041.

- Hainan Lu; Jianteng Sun; Lizhong Zhu; The role of artificial root exudate components in facilitating the degradation of pyrene in soil. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 7130-7130, 10.1038/s41598-017-07413-3.

- Irene Kuiper; Ellen L. Lagendijk; Guido V. Bloemberg; Ben J. J. Lugtenberg; Rhizoremediation: A Beneficial Plant-Microbe Interaction. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions® 2004, 17, 6-15, 10.1094/mpmi.2004.17.1.6.

- Nele Weyens; Sofie Thijs; Robert Popek; Nele Witters; Arkadiusz Przybysz; Jordan Espenshade; Helena Gawrońska; Jaco Vangronsveld; Stanislaw W. Gawronski; The Role of Plant–Microbe Interactions and Their Exploitation for Phytoremediation of Air Pollutants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2015, 16, 25576-25604, 10.3390/ijms161025576.

- Fernando Rojo; Carbon catabolite repression inPseudomonas: optimizing metabolic versatility and interactions with the environment. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2010, 34, 658-684, 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00218.x.

- Elisa Terzaghi; Chiara Maria Vitale; Georgia Salina; Antonio Di Guardo; Plants radically change the mobility of PCBs in soil: Role of different species and soil conditions. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 388, 121786, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121786.

- Sara Rodriguez-Conde; Lázaro Molina; Paola González; Alicia García-Puente; Ana Segura; Degradation of phenanthrene by Novosphingobium sp. HS2a improved plant growth in PAHs-contaminated environments. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2016, 100, 10627-10636, 10.1007/s00253-016-7892-y.

- Steven E. Lindow; Maria T. Brandl; Microbiology of the Phyllosphere. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2003, 69, 1875-1883, 10.1128/aem.69.4.1875-1883.2003.

- Robert Popek; Adrian Łukowski; Christopher Bates; Jacek Oleksyn; Accumulation of particulate matter, heavy metals, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on the leaves of Tilia cordata Mill. in five Polish cities with different levels of air pollution. International Journal of Phytoremediation 2017, 19, 1134-1141, 10.1080/15226514.2017.1328394.

- Britt Koskella; The phyllosphere. Current Biology 2020, 30, R1143-R1146, 10.1016/j.cub.2020.07.037.

- Shigenobu Yoshida; Syuntaro Hiradate; Motoo Koitabashi; Tsunashi Kamo; Seiya Tsushima; Phyllosphere Methylobacterium bacteria contain UVA-absorbing compounds. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2017, 167, 168-175, 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.12.019.

- Andrea Franzetti; Isabella Gandolfi; Giuseppina Bestetti; Emilio Padoa Schioppa; Claudia Canedoli; Diego Brambilla; David Cappelletti; Bartolomeo Sebastiani; Ermanno Federici; Maddalena Papacchini; et al. Plant-microorganisms interaction promotes removal of air pollutants in Milan (Italy) urban area. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 384, 121021, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121021.

- Karen Waight; Onruthai Pinyakong; Ekawan Luepromchai; Degradation of phenanthrene on plant leaves by phyllosphere bacteria. The Journal of General and Applied Microbiology 2007, 53, 265-272, 10.2323/jgam.53.265.

- Gabriel Pérez; Julià Coma; Ingrid Martorell; Luisa F. Cabeza; Vertical Greenery Systems (VGS) for energy saving in buildings: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2014, 39, 139-165, 10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.055.

- P.J. Irga; N.J. Paull; P. Abdo; F.R. Torpy; An assessment of the atmospheric particle removal efficiency of an in-room botanical biofilter system. Building and Environment 2017, 115, 281-290, 10.1016/j.buildenv.2017.01.035.

- Li Guo; Shuli Ma; Dongsen Zhao; Bo Zhao; Bingfang Xu; Jiwen Wu; Jin Tong; Donghui Chen; Yunhai Ma; Mo Li; et al. Experimental investigation of vegetative environment buffers in reducing particulate matters emitted from ventilated poultry house. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 2019, 69, 934-943, 10.1080/10962247.2019.1598518.

- Lisandra Santiago Delgado Trine; Eva L. Davis; Courtney Roper; Lisa Truong; Robert L. Tanguay; Staci L. Massey Simonich; Formation of PAH Derivatives and Increased Developmental Toxicity during Steam Enhanced Extraction Remediation of Creosote Contaminated Superfund Soil. Environmental Science & Technology 2019, 53, 4460-4469, 10.1021/acs.est.8b07231.

- Peter Fantke; Jon A. Arnot; William J. Doucette; Improving plant bioaccumulation science through consistent reporting of experimental data. Journal of Environmental Management 2016, 181, 374-384, 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.06.065.

- M. Amine Hassani; Paloma Durán; Stéphane Hacquard; Microbial interactions within the plant holobiont. Microbiome 2018, 6, 1-17, 10.1186/s40168-018-0445-0.

- Yanmei Chen; Qiaobei Ding; Yuanqing Chao; Xiange Wei; Shizhong Wang; Rongliang Qiu; Structural development and assembly patterns of the root-associated microbiomes during phytoremediation. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 644, 1591-1601, 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.095.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!