The offshore wind is the sector of marine renewable energy with the highest commercial development at present. The margin to optimise offshore wind foundations is considerable, thus attracting both the scientific and the industrial community. Due to the complexity of the marine environment, the foundation of an offshore wind turbine represents a considerable portion of the overall investment. An important part of the foundation’s costs relates to the scour protections, which prevent scour effects that can lead the structure to reach the ultimate and service limit states. Presently, the advances in scour protections design and its optimisation for marine envi-ronments face many challenges, and the latest findings are often bounded by stakeholder’s strict confidential policies.

- scour

- protection

- wave energy

- tidal energy

- offshore wind energy

Note: The following contents are extract from your paper. The entry will be online only after author check and submit it.

1. Introduction

Offshore wind energy (OWE) is one of the largest forms of clean energy and a sector in clear expansion over the last decades [1–4]. Europe is the leader in installed offshore wind farms [2], and its growth could be explained, due to the major role that wind energy plays in the achievements of the 20-20-20 targets defined by the European Union (EU) [5]. According to the Central Scenario in Reference [6], a 70 GW of offshore cumulative wind energy capacity are expected, producing 888 TWh of electricity, equivalent to 30% of EU’s power demand and meeting the 27% renewable energy benchmark established for the beginning of 2030.

Offshore wind is around 50% more expensive than onshore wind, being towers and foundations 350% more costly than the ones used in onshore turbines [7]. The foundations represent, on average, about 30% of the structure’s total investment [8,9], with a considerable part being related to scour protections [4]. Therefore, the optimisation of scour protections can have a direct impact on the LCoE—levelised cost of energy—which represents the ratio between the structure lifetime cost’s and energy production [10]. This impact can occur via the capital expenditure (CAPEX) or the operational expenditure (OPEX), mainly because such optimisations are often related to the reduction of the stone material and transport costs applied to the initial solution (CAPEX optimisation) or to the reduction of re-filling operations after the occurrence of extreme storm events (OPEX optimisation).

Scour protections are seen as a preferential contribution to lowering the LcoE and have registered major developments in the past 10 to 12 years. It is expected that such developments can, in time, be extended to wave and tidal energy foundations as well.

Key contributions include, for example, the wide-graded and dynamic scour protections or the application of probabilistic design methods [11–13]. However, the field implementation of such concepts and design methodologies still poses challenging knowledge gaps, which are yet to be fully addressed. The offshore wind sector, which sets the pace for many of the optimisations that are then extended to other sectors of marine renewables, has been focused on major trends towards higher profitability, including the repowering of existing foundations [4], the re-adaptation of oil and gas structures to wind energy production, the development of complex foundations [14] or new hybrid foundations with more than one type of energy conversion, e.g., combined wind and waves [15].

Depending on the site conditions, these trends may enhance the use of scour protections, which need to be designed to account for the added complexity of new geometries of the foundation, the disturbance of the flow-fields, due to the presence of energy converters, the extended life-time cycle of already existing foundations, the occurrence of severe damage, among several other aspects, which remain to be fully understood.

The new trends for the development of offshore wind foundations have a direct impact on the design of the protections, due to its influence on the damage in the rubble mound armour layers with complex geometry, i.e., varying thickness and horizontal extension. The damage behaviour of rubble mound armour layers under different loading and design conditions is still to be known in detail, and new studies are now focusing on improving the resulting damage description, e.g., References [16,17].

Furthermore, new fields of Marine Renewable Energy are now rising towards several demonstrations and large scale in situ projects, owing to its large potential to capture the untapped ocean energy resources [18]. However, the design of scour protections for foundations with movable energy converters, whose motion impacts the waves-current profile, is yet to reach a mature state of knowledge.

Unlike other maritime structures, e.g., breakwaters, quay-walls or groins, the knowledge needed to design scour protections is hold by a restrictive number of experts in the industry and academia, which is a result of the harsh confidential policies adopted by the stakeholders of the sector [4]. This results in the absence of enough benchmark data available to explore and solve the existing knowledge gaps, particularly in large-scale studies. Only, more recently, this data has been partially compiled and extended in studies, such as References [13,16].

Given the new trends for offshore foundations and the most recent contributions made, reviewing the research needs, challenges and recent findings associated with scour protections represent an important contribution for a systematic guidance on optimising offshore foundations. Hence, providing opportunities to increase the competitiveness of marine energy harvesting technologies, from the most developed ones, i.e., offshore wind energy, to the ones that are still striving for a mature commercial stage, i.e., wave, tidal and marine currents energy. The challenges arising on this topic are numerous, and a thorough review focused on the latest findings is important to summarise current knowledge and outline future research lines.

Aiming to contribute to a deeper notion on the existing knowledge gaps that contribute for an over-conservative design and high costs of scour protections, the main goal of this article is to summarise and highlight the most recent research on scour protections, with particular emphasis on the dynamic, and wide-graded rip-rap systems.

2. Conceptual Optimisations

2.1. Scour Protection Conceptual Designs

Scour protections have an important role in offshore wind turbine design. Rip-rap (rubble mound material) protections are a common type of protection, due to their low cost and material availability [3].

It should be noted, however, that the cost of scour protective measures may vary from one case to another, depending on several factors, as the location or the material stock at nearby regions. In addition, the material stock, transport and installation costs may depend on the required stone size. Therefore, rip-rap scour protections may not always be the most affordable solution. Nevertheless, although the studies performed on different scour countermeasures in the marine environment, e.g., References [19–21], rip-rap scour protections remain as one of the most widely used, hence being the focus of this review. Depending on the stability concept applied, these can be separated into three major groups (also see References [22–24]):

- Static Protections: Stone movement in the armour layer is not allowed;

- Dynamic Protections: Stone movement is allowed if the protection does not fail;

- Wide-graded protections, which consist of an armour layer of wide-graded material without a granular filter. These might be designed to be both statically or dynamically stable.

While static scour protections have been widely employed in commercial offshore wind projects, using dynamic scour protections (wide-graded or not) is yet to be widely applied. However, it is important to mention that often novel and optimised concepts, which may have been successfully implemented in the field, are not extensively announced to the scientific and professional community. This is due to the heavy restrictions posed by non-disclosure agreements between stakeholders.

Therefore, it is hard to assess the actual implementation of such concepts. Nevertheless, the focus on dynamic scour protections started about 12 years ago, with the systematised design proposal made by Reference [25], despite the preliminary studies presented by Reference [26].

Regardless of the lack of data for the commercial application of dynamic scour protections, Reference [1] indicates that these are expected to have a thickness of rubble mound layer generally varying between 0.30 m to 0.40 m, which compares to thicknesses of 0.5 to 1.0 m (sometimes higher) in the traditional static scour protection.

However, such differences in the thickness depend on the optimisation of the median stone size (D50), since its reduction, which can go up to 80% according to Reference [23], may require an increase of the thickness to sustain the acceptable damage level without failure occurrence. Therefore, reducing the stone size too much may require a large increase in the thickness, which may contribute to increasing the costs of the dynamic solution. Moreover, it is important to account for operation and maintenance costs that may arise from the need to refilling the dynamic protection after severe storms. These costs are reduced if a static solution with very large stone sizes is applied. Therefore, the actual optimisation needs to be assessed on a case-to-case basis and always accounting for the CAPEX and OPEX parcels throughout the lifecycle of the foundation (also see Section 2.3).

2.2. Static Scour Protections

Since in static scour protections, the movement of the rubble mound material is not allowed, the design is based on the threshold of motion criterion. This means that the median stone size needs to be such that the wave-and-current-induced shear stress does not surpass the critical shear stress of the protection material [3,27]. Such size can also be varied depending on the density of the rubble material to be used. In Reference [22], it is shown through physical modelling for two stone materials, with densities of 2650 kg/m3 and 3200 kg/m3, that the damage of the protection can be reduced if higher stone’s densities are used. For the environmental conditions given, the design of a static scour protections consists of defining the critical stone size (Dcr), which ensures that no movement occurs at the top layer.

Many formulations were adapted to determine the Dcr (m), e.g., a recent comparison of different formulas to obtain Dcr in the marine environment is given in Reference [28], which includes the comparison with formulas derived for the fluvial environment only. It was shown that the applicable formulations may lead to very different results in terms of stone sizes and weights. Nevertheless, in common design situations, the wave- and current-induced shear stresses are combined and then compared with the critical shear stress given by Reference [27]:

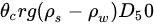

|

τcr = |

(1) |

where θcr is the critical Shields parameter, which for non-cohesive soils and a dimensionless grain size D* larger than 100 (see Reference [27]) corresponds to the asymptotic value of 0.056.

In Reference [22], an alternative way to obtain the maximum wave- and current-induced shear stress is given, and a new quantification of the critical shear stress is proposed. This new shear stress is calculated based on the D67.5 instead of D50 and θcr = 0.035.

The reason behind this is that Reference [22] noted that smaller stones in scour protections with narrow graded material tended to move faster than if a wide-graded material was used. It was noted that often these smaller stones could present singular movements without an actual generalised violation of the static stability. In compensation, a smaller value of the critical Shields parameter was used, thus contributing to a conservative estimation of the critical shear stress. In Reference [11], it was shown that the critical shear stress according to Reference [22] was still less conservative than the formulation given by Reference [27], which could eventually reduce the design value Dcr.

However, the number of tests used to define the onset of motion, i.e., static stability, in Reference [22] led to a regression formula that combines the wave- and current-induced shear stress, which has a considerable degree of uncertainty. At the end of the day, this poses an important setback to its application instead of Reference [27], which was extensively validated for undisturbed conditions, i.e., without a foundation placed at the seabed.

The application of Reference [27] to monopile foundations, or any other type of foundation, in fact, implies the use of an amplification factor, which accounts for the increase in the wave- and current-induced shear stresses, due to the presence of the foundation. The definition of the amplification factor is often hard, and is very empiric in nature. In monopile foundations, defining the amplification factor could be a simpler task, since classic references as References [29,30] widely address this aspect. In complex geometries, however, the difficulty increases considerably, and the majority of the projects require physical and numerical models to assess the proper amplification factor to be used. The formulation given by Reference [22] does not imply the use of an amplification factor, since it was derived specifically for monopiles. Conversely, its application is rather limited, and the extrapolation for complex geometries of the foundation is not straightforward.

2.3. Dynamic Scour Protections

In 2004, the first proposal of a dynamically stable scour protection was introduced by Reference [26] as a result of the OPTI-PILE project [31]. The OPTI-PILE project, destined to optimise the scour protection design, introduced the so-called stability parameter (stab), to classify protections according to three levels of damage (static, dynamic, failure). It was concluded that dynamic protections could be built using smaller median stone sizes (D50) when compared to the static protections. The stability parameter was defined as the ratio between the maximum dimensionless wave- and current-induced shear stress (θmax) and the dimensionless critical shear stress (θcr):

|

stab = |

(2) |

The introduction of the stab parameter marked the beginning of a new design paradigm in scour protections for the offshore marine environment. In this new paradigm, the threshold of motion is no longer the criteria for stability; instead, the rubble mound material is allowed to have a certain degree of movement, as long as the filter layer does not present an exposure area equal to, or larger, than 4D502—i.e., an equivalent square with a size equal to two stones with size D50 by D50.

The following states of stability/failure were defined in Reference [26]:

- Static stability: stab < 0.4155;

- Dynamic stability: 0.4155 ≤ stab ≤ 0.460;

- Failure: stab > 0.460.

In this type of protection, the development of scour pits is allowed to develop until their equilibrium stage [26], then a two layers protection is placed (granular filter and rubble mound top layer). According to Reference [26], dynamic scour protections reshape the armour layer, i.e., stones previously moved may return to the initial position, for example, when currents reverse. Since static protections have proven to be conservative driven, the possibility of having movement of stones without failure allows for a smaller stone diameter to be used—thus lowering the costs at offshore wind foundations, namely, the ones related to transportation, installation and rubble material acquisition. However, the possibility of reshaping may imply regular monitoring of the protection’s damage after storm events, to ensure no excessive exposure of the filter layer has occurred. Thus, in practical cases, it is often common to compare the CAPEX and OPEX parcels of both static and dynamic scour protections, to ensure that the maintenance of a dynamic solution is not overcoming the savings made in CAPEX parcel when compared to a static solution. Still, an important aspect is that often static scour protections fail and require further expenditures on the OPEX parcel as well; this has been addressed by Reference [32], with field surveys in known protected offshore wind turbines, e.g., in Egmond aan Zee (NLD) and Horns Rev (DEN) offshore wind farms.

The stability parameter is also, in a certain way, dependent on the amplified bed shear stress, due to the presence of an offshore foundation. Later on, in 2008, a key breakthrough was introduced by Reference [25], also presented in 2012 by Reference [23], which provided an alternative design for dynamic scour protections based on the damage parameter. Based on extensive physical modelling activities, following a Froude similitude and a geometric scale of 1:50, Reference [25] noted that the stab parameter failed to predict the onset of motion for scour protections tested under different hydrodynamic conditions. Hence, looking for a simplified design procedure, the damage number (S3D) was introduced. The S3D was not directly dependent on the critical shear stress, thus surpassing some of the limitations of calculating the critical shear stress and the maximum shear stress induced by local conditions. In fact, the damage number finds its resemblance in Van der Meer’s damage number developed for breakwaters [33], which also show the ability to develop a stable profile under dynamic conditions of the armour layer material.

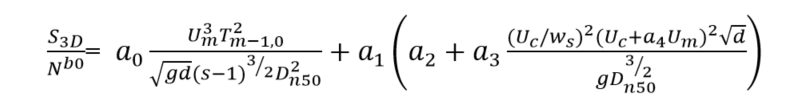

For design purposes, Reference [23] proposes the following formula to quantify the damage number of scour protections:

|

|

(3) |

where N is the number of waves, g (m2/s) is the acceleration of gravity, d is the water depth, s is the ratio between the density of the rock material (ρs) and the water density (ρw), Um (m/s) is the orbital bottom velocity, Uc (m/s) is the depth-average velocity and the regressions coefficients a0, a2, a3 and b0 are equal to 0.00076, −0.022, 0.0079 and 0.243, respectively [23]. The settling velocity (ws) and the coefficients a1 and a4 are also defined in Reference [23]. Similarly, to Reference [26], the failure criteria used by References [23,25] was also the exposure of the filter layer to an area equal to 4. The following limits for the damage number were defined:

- Static stability: S3D < 25;

- Dynamic stability: 0.25 < S3D < 1;

- Failure: S3D ≥

While the damage number, does not require the quantification of the amplification factor, other uncertainties can be found in its definition, namely, the limited conditions for which it was initially developed. For example, although being a result of a considerably large number of scour protection tests (85 tests), the range of water depths and armour layer thicknesses tested was rather reduced.

Other studies, e.g., References [34–36] tried to extend the testing conditions of the formula, all these reaching the conclusion that the limits established for the stability of the scour protection showed overlapping situations, thus the failure of a dynamic scour protection could occur for values above 1.00. This was also initially noted by Reference [23], which proposed a suitable limit within a conservative design perspective. Still, the space for improvement of the present formula’s accuracy exists and is an important aspect of ensuring that dynamic scour protections reach a similar level of maturity as the static design. Moreover, the damage number was specifically developed for monopiles, and its application to other complex structures is also not straight forward, since there are regression coefficients to be adjusted in the prediction formula.

2.4. Wide-Graded Protections

Rip-rap scour protections are regularly designed with two layers, first granular material is applied and then a rubble mound layer is placed on top. However, in line with the laboratory observations made by References [12,24,37,38], formally introduced and developed the wide-graded protection optimisation, which used a single layer with a very extensive granulometric curve, whose stability was expected to be increased in comparison to narrow graded protections. This assumption was based on the fact that in wide-graded materials, smaller stones could find better shelter among the largest ones, with the voids of the protection being reduced, thus contributing to the stability of the overall. Reference [12] showed that for wide-graded mixtures, the washout of finer particles was less likely to occur.

Reference [12] tested wide-graded protections under waves and currents. Reference [12] determined fractional critical shear stresses through velocity measurements and noted the occurrence of highly selective incipient motion of individual fractions under steady current conditions. The selective mobility of this wide-graded material could not be expressed by the Shields approach. A stable and almost immobile protection surface was observed under the currents, indicating a provisional static armour layer. Whereas, under waves, wide-graded armour layers tend to be quite stable. The scour pattern observed around the monopile had a maximum depth at the protection almost identical both in front and at the back of the monopile. However, after 9000 waves, a final equilibrium scour depth was not reached at a distance of 1.5Dp from the centre of the monopile. The use of 9000 waves, as a reference for testing wide-graded materials, was not previously used in the tests that led to the development of dynamic scour protections, e.g., References [25,26] and remaining ones. This poses an interesting question in terms of results comparison, and a clear indication is given by Reference [4], which states that results referring to long-duration tests, i.e., above 5000 waves, are still needed in larger numbers in the literature.

Reference [39] performed 46 scour tests, using a singular graded scour protection, and concluded that for wide-graded protections, at the top of the protection singular layer, the finer fractions are removed, by an armouring process, and mainly due to the action of the horseshoe vortex, leading to a partial settlement of the surface layer. Beneath the top, the material properties remain, revealing that scour from the top reaches an apparent equilibrium. The observed equilibrium scour was about 2D50, whereas the settlement was about 1D50. The studies performed in References [12,24,37–39] provide strong indications on the feasibility of static and dynamic scour protections made out of a single wide-graded layer, which may contribute to lower costs of installation and material preparation, since no granular filter is needed. More recently, two large-scale scour protection tests are also analysed in Reference [13]. However, the most recent analysis of such data set, made by Reference [13], was more focused on the behaviour of two-layered dynamic protections, thus the literature still shows a lack of data and results discussion in terms of wide-graded scour protections, particularly in situ and in large scale models. Additionally, it is important to note that the dynamic design based on the damage number, relates to the exposure of the filter layer, which is not applicable to wide-graded protections. Eventually, the damage number associated with failure could be defined for the exposure of the actual sand bed. Nevertheless, a detailed discussion of the stability and failure boundaries for wide-graded protections is yet to be fully addressed in the literature.

Another interesting aspect of rip-rap scour protection relates to the pore pressure registered inside and beneath the protection layer, which may lead to the sinking failure mode as a consequence of the suction of the material placed as a filter or the actual sand-bed sediments [40]. In wide-graded scour protections, the volume of voids might be considerably smaller than in a narrow-graded protection and scour protections with two layers. Therefore, the hydraulic gradient is different, which in turn affects the potential for material to be washed out and transported away from the protection. Recently, Reference [41] provided insights on the onset of motion beneath scour protections made of rubble mound material. However, the effects of the grading were not investigated in detail. Still, important outcomes were derived for waves and currents combined and acting alone. It was found that the onset of motion of the sediment underneath the scour protection was dependent on the sediment properties and the thickness of the scour protection (among other variables). This clearly indicates that it is worth further investigate the pore pressure on wide-graded materials, which have a tendency for sort out finer fractions on top of the protection, but that can remain intact at lower levels of the protection’s thickness, as mentioned by Reference [39].

The literature shows a lack of reported field applications of wide-graded scour protections. Still from the design point of view, they are faced as an interesting alternative, since the stability of the protection has been shown to benefit from the wide gradation. In addition, from the installation point of view, the no need for a filter layer placement is also an appealing detail. In practical terms, installing these protections, typically made with fall pipe vessels, needs to be considered, since the act of dropping the wide-graded material in offshore conditions, even in good weather windows, may always lead to a loss of the finer fractions. This occurs because the fall velocity is not the same for all fractions, and some of them are more prone to be dragged away during the settlement process than others, before reaching the sea bottom. Hence, the installation process may influence the performance of this solution and also represents a relevant aspect for future applied research.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jmse9030297