Inflammasomes are components of the innate immune response that have recently emerged as crucial controllers of tissue homeostasis. In particular, the nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich-containing (NLR) family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is a complex platform involved in the activation of caspase-1 and the maturation of interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18, which are mainly released via pyroptosis. Pyroptosis is a caspase-1-dependent type of cell death that is mediated by the cleavage of gasdermin D and the subsequent formation of structurally stable pores in the cell membrane.

- hypertension

- pyroptosis

- inflammasome

- inflammation

1. Inflammation and Hypertension

Elevated blood pressure, defined as a systolic pressure higher than 130 mmHg and diastolic pressure greater than 80 mmHg [1], is the leading risk for cardiovascular and kidney diseases [2] and was reported to affect 1.13 billion people in the world in 2016 [3]. As a consequence, high blood pressure is a leading cause of death worldwide [4] and research in the field of hypertension is highly dynamic. Extensive evidence demonstrates an important role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of hypertension and vascular and kidney diseases. A series of elegant studies performed by Grollman et al. in the 1960s first evidenced that autoimmune factors play a critical role in an animal model of renal infarction-induced hypertension [5][6]. The same group also reported that hypertension could be transferred to normotensive rats by transplanting lymph node cells from rats with renal infarction hypertension [7]. In the 1970s, Svendsen revealed that an intact thymus is required for the maintenance or development of hypertension in three different animal models of the disease: the deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) salt model [8], mice with partially infarcted kidneys [9], and the genetically hypertensive NZB/Cr mouse strain [10].

Since those early studies, investigation of the interplay between inflammation and high blood pressure has grown exponentially, and more than 18,000 publications have explored this topic to date. It is now widely acknowledged that low-grade or persistent inflammation is a key player in the development and maintenance of hypertension. Exhaustive research demonstrates the infiltration of immune cells, like T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells in the kidneys, perivascular fat, or heart during the development and progression of hypertension [11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24]. In particular, immune cell transfer studies performed by Guzik et al. [15] demonstrated that the development of angiotensin II-induced and DOCA salt-induced hypertension was dependent on the presence of T cells. Moreover, pharmacological inhibition of immune cells with, for instance, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, or cyclophosphamide attenuates the development of high blood pressure [25][26][27][28][29]. More recently, the genetic ablation of certain immune cells and specific receptors on immune cells or cytokines demonstrates that activation of immune cells like T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells [18][23][30][31][32][33][34][35] is essential for the development of elevated blood pressure. Lately, B cells have also been reported to be important in the development of hypertension [36]. The role of immune cells from the adaptive and innate arms of the immune response as well as different cytokines in hypertension has been extensively reviewed elsewhere, and thus, we will not review it here [37][38][39][40][41][42].

As mentioned above, inflammatory cells have been repeatedly demonstrated to infiltrate organs involved with blood pressure regulation, including the vasculature, the kidneys, and the brain [40][43][44], during hypertension. For instance, in a hypertensive kidney, macrophages and T cells localize around glomeruli and arterioles and within the interstitium [45][46]. Similarly, infiltration of immune cells and increased levels of inflammatory mediators have been demonstrated in the perivascular fat of large arteries and arterioles in animal models of hypertension [45]. Activated inflammatory cells produce and release cytokines like tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-17, IL-6, and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) that are known inducers of renal and vascular dysfunction [33][34][35][47][48][49]. Many of those inflammatory mediators are known to stimulate fibrosis [47][50][51], for instance, which is seen in both vessels and kidneys of hypertensive patients and animal models of the disease. In addition, T cells and macrophages contain all the machinery needed for the production of vasoactive molecules such as angiotensin II [52][53][54], endothelin-1 [55][56], or prostaglandins [57][58], which are known mediators of hypertension and hypertension-induced end-organ damage. Moreover, a number of inflammatory factors released by activated immune cells can also modulate the local production of angiotensinogen and, later, angiotensin II generation within the kidneys, vasculature, or nervous system [51][59][60]. This implies that inflammatory cells increase the local levels of pro-hypertensive stimuli and can further increase blood pressure by stimulating fluid retention and vascular constriction [61]. Interesting animal studies have also shown that IL-17 or IFN-γ deficiency is associated with alterations of sodium (Na+) transporters in the kidneys and, consequently, reduced Na+ retention in hypertensive conditions [62]. Despite all this evidence linking immune cell infiltration and the development and progression of hypertension, the exact mechanisms that trigger low-level inflammation observed in the elevated blood pressure setting still remain unclear.

2. Inflammasomes and Pyroptotic Cell Death

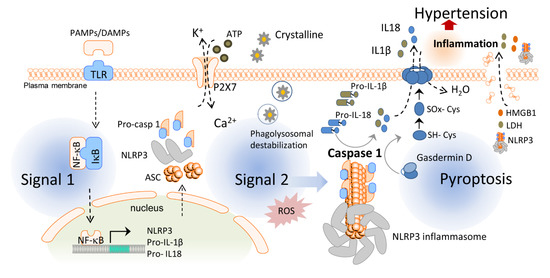

Inflammasomes are essential players in the inflammatory response and one of the first steps for the initiation of chronic low-grade inflammation. Inflammasomes are intracellular protein oligomers that are sensors for pathogens, tissue injuries, and recognition of the signals altering homeostasis. They are composed of an effector protein, an adaptor protein, and a sensor protein that oligomerize in a large complex after activation. The inflammasome sensor protein is usually a pattern recognition receptor (PRR) that oligomerizes after activation induced by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), endogenous host-derived damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), or homeostasis-altering molecular processes (HAMPs) [63]. Three families of sensor proteins have been described, belonging to the nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich-containing family of receptors (NLRs), the absent in melanoma 2-like receptors (ALRs) or pyrin, which give name to the inflammasome and share analogous structural domains. Moreover, there are several types of inflammasomes, such as NLRP1b (mouse), NLRP3, NLR family CARD domain-containing protein 4 (NLRC4), NLRP6, NLRP9, pyrin, and absent in melanoma (AIM) 2. A great variety of molecules activate different sensor proteins, including Bacillus anthracis for NLRP1b, Salmonella typhimurium for NLRC4, lipoteichoic acid for NLRP6, viral dsRNA for NLRP9, dsDNA for AIM2, toxin-induced modifications of Rho GTPases for pyrin, and several PAMPs, DAMPs, and HAMPs for NLRP3 [64]. After activation, the sensor protein oligomerizes and recruits the adaptor protein apoptosis-associated speck-like protein with the caspase recruitment domain (ASC) forming large filaments by prion-like oligomerization [65]. ASC filaments recruit the effector zymogen pro-caspase-1 by caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD)–CARD homotypic interaction, facilitating its autoactivation by close proximity [66]. However, other inflammasomes can be activated without involvement of ASC, such as NLRC4 [67]. Activated caspase-1 induces the cleavage of gasdermin D and releases its lytic N-terminal domain (GSDMDNT) [68][69] from its C-terminus repressor domain to form pores in membranes. GSDMDNT lyses mammalian cells by acting from the inside of the cells and also has anti-bacterial activity [70]. Studies of the full-length crystal structure of GSDMD reveals distinct features of auto-inhibition among the gasdermin (GSDM) family members [71]. Released GSDMNT domains bind to negatively charged membrane lipids like phosphatidylinositol phosphate, cardiolipin, and phosphatidylserine [72]. Caspase-1 activation also mediates the proteolytic cleavage of the inactive precursor cytokines pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 to produce their active forms that are mainly released by GSDMD pores, which have a diameter of 10–14 nm and are big enough to release the mature form of these cytokines [70] (Figure 1). The GSDMD pore consists of about 54 N-terminal gasdermin subunits with a radical conformational change compared to their conformation in the full GSDM sequence, with extensive interactions among the inserted β-strands and the α-helix 1 localized in the globular domain [73]. Upon permeabilization of the plasma membrane by GSDMD pores, cells undergo a lytic, pro-inflammatory cell death known as pyroptosis that further promotes and increases the release of mature IL-1β and IL-18 and the induction of a pro-inflammatory environment [74]. If gasdermin pores at the plasma membrane are not repaired, pyroptosis will end with a burst in pro-inflammatory cytokine release and the discharge of large intracellular components (such as inflammasome oligomers or high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) among others), resulting in a highly pro-inflammatory cell death process [68]. Unlike other programmed cell deaths, pyroptosis has been described as a strategy to preserve the inflammatory response through the release of pro-inflammatory intracellular content during plasma membrane permeabilization [75][76][77], a process that recruits immune cells to combat invading infectious organisms and promote tissue healing [78]. Pyroptosis was initially reported in macrophages infected with Salmonella typhimurium [79], but later it was also demonstrated in other cell types and in response to different signals [80]. Since then, pyroptosis has been associated with multiple diseases such as cardiovascular, liver, kidney, inflammatory, and immune diseases or cancer [81].

Figure 1. Activation of the inflammasome and pyroptosis induce hypertension. In the first step of the inflammasome activation, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) stimulate toll-like receptors (TLR) and the translocation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) to the cell nucleus, which, in turn, increases the transcription of the nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich-containing (NLR) family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome sensor, its posttranscriptional modification, and expression of pro-interleukin (IL)-1β and pro-IL-18. The second signal such as crystalline particles or P2X purinergic receptor 7 (P2 × 7) activation via ATP induces the oligomerization of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex which leads to the activation of caspase-1. Caspase-1 cleaves gasdermin D and converts pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into mature IL-1β and IL-18. Pyroptosis occurs by the insertion of the N-terminal fragment of gasdermin D into the plasma membrane, creating oligomeric pores and allowing for the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18 to the extracellular space. Pore formation also induces water influx into the cell, cell swelling, and osmotic cell lysis which induce further inflammation and hypertension by releasing more inflammatory products from the intracellular space. HMGB1: high mobility group box 1; IκB: inhibitor of κB; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase.

In humans, GSDM family members are composed of 6 members: GSDMA, B, C, D, E, and Pejvakin (PJVK), and all have a highly conserved N-terminal domain that induces pyroptosis when expressed ectopically, except for PJVKNT [68]. Pyroptosis depends on different innate immune pathways leading to GSDMD processing. Caspase-1 is one of the most studied proteases involved in pyroptosis by GSDMD cleavage. However, GSDMD cleavage and pyroptosis are also executed by other inflammatory caspases: human caspase-4 and -5 and mouse caspase-11 [80][82]. Moreover, other caspases (like apoptotic caspase-3 or -8) and proteases (like elastase or granzyme) can also elicit processing of GSDMB, D, and E and induce pyroptosis [83].

NLRP3 is the most studied member of the inflammasome family as it has been implicated in the pathophysiology of several autoinflammatory syndromes [84] and other diseases associated with metabolic, degenerative, and inflammatory processes [85]. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome can be induced in two different manners: the “canonical” and “non-canonical” pathways.

Canonical NLRP3 inflammasome activation begins with a priming signal driven by several classes of receptors facilitating the upregulation of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β via nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling and also key post-translational modifications of NLRP3. An activation signal is then initiated by PAMPs, DAMPs, or HAMPs, inducing physiological changes that are detected by NLRP3 and followed by the recruitment of ASC and caspase-1 to form the inflammasome complex [86]. Among the activators of this cascade, our group found different microorganisms, bacterial pore-forming toxins, hemozoin, or even melittin [87][88]. NLRP3 can also be activated by the phagocytosis of particulate matter (silica, alum, asbestos, uric acid crystals, cholesterol crystals, or β-amyloid deposits) as well as by cell swelling [89] or extracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) acting through the P2X purinoceptor 7 (P2X7) [90]. This activation signal islinked to mitochondrial dysfunction, lysosomal destabilization or plasma membrane damage, which result in cell metabolic changes, reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, potassium (K+) and chloride (Cl–) efflux, and calcium (Ca2+) influx [91]. Although the exact mechanism leading to NLRP3 activation is not well-known, K+ efflux is a common initial step for NLRP3 activation in response to most of the triggers [92][93].

In the non-canonical inflammasome pathway, gram-negative bacteria activate the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)–toll IL-1 receptor (TIR)-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon (IFN)-β (TRIF) signaling pathway leading to type I IFN production and upregulation of guanylate-binding proteins (GBPs) and immunity-related GTPase family member B10 (IRGB10), which in turn target outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) or bacterial and vacuolar membranes to facilitate the release of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) into the cytoplasm [94]. LPS can directly interact with murine caspase-11 or human caspase-4/5 and activate NLRP3 as a consequence of K+ efflux induced by GSDMD pores in the cell membrane or after sensing DAMPs released by pyroptotic cells, suggesting a functional crosstalk between the canonical and non-canonical pathways [95].

On the other hand, GSDMD pore formation has been found responsible for IL-1β release in the absence of pyroptotic cell death [96]. Likewise, calcium influx through GSDMD pores can act as a signal to induce membrane repair by recruiting the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) machinery to damaged plasma membrane areas, inducing cell survival mechanisms beyond pyroptosis [97]. Moreover, IL-1β release upon activation of caspase-1 can be independent of GSDMD membrane permeabilization [98]. The different mechanisms involved in the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is a topic of active investigation and thus, in addition to the mechanisms described above, alternative molecular mechanisms have also been unveiled recently. Because of space concerns, we only reviewed here the more established mechanisms, but we refer the reader to [99][100][101] for a more detailed description of these novel mechanisms.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22031064

References

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Collins, K.J.; Dennison Himmelfarb, C.; De Palma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2018, 138, e484–e594.

- Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors for Chronic Diseases Collaboration. Cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes mortality burden of cardiometabolic risk factors from 1980 to 2010: A comparative risk assessment. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 634–647.

- Outeda, P.; Menezes, L.; Hartung, E.A.; Bridges, S.; Zhou, F.; Zhu, X.; Xu, H.; Huang, Q.; Yao, Q.; Qian, F.; et al. A novel model of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney questions the role of the fibrocystin C-terminus in disease mechanism. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 1130–1144.

- Bromfield, S.; Muntner, P. High blood pressure: The leading global burden of disease risk factor and the need for worldwide prevention programs. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2013, 15, 134–136.

- Sokabe, H.; Grollman, A. A study of hypertension in the rat induced by infarction of the kidney. Tex. Rep. Biol. Med. 1963, 21, 93–100.

- White, F.N.; Grollman, A. Autoimmune Factors associated with infarction of the kidney. Nephron 1964, 1, 93–102.

- Okuda, T.; Grollman, A. Passive transfer of autoimmune induced hypertension in the rat by lymph node cells. Tex. Rep. Biol. Med. 1967, 25, 257–264.

- Svendsen, U.G. Evidence for an initial, thymus independent and a chronic, thymus dependent phase of DOCA and salt hypertension in mice. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. A 1976, 84, 523–528.

- Svendsen, U.G. The role of thymus for the development and prognosis of hypertension and hypertensive vascular disease in mice following renal infarction. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. A 1976, 84, 235–243.

- Svendsen, U.G. The importance of thymus for hypertension and hypertensive vascular disease in rats and mice. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. Suppl. 1978, 267, 1–15.

- Caillon, A.; Mian, M.O.R.; Fraulob-Aquino, J.C.; Huo, K.G.; Barhoumi, T.; Ouerd, S.; Sinnaeve, P.R.; Paradis, P.; Schiffrin, E.L. γδ T cells mediate angiotensin ii-induced hypertension and vascular injury. Circulation 2017, 135, 2155–2162.

- Rodríguez-Iturbe, B.; Vaziri, N.D.; Herrera-Acosta, J.; Johnson, R.J. Oxidative stress, renal infiltration of immune cells, and salt-sensitive hypertension: All for one and one for all. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2004, 286, F606–F616.

- Johnson, R.J.; Rodriguez-Iturbe, B.; Nakagawa, T.; Kang, D.H.; Feig, D.I.; Herrera-Acosta, J. Subtle renal injury is likely a common mechanism for salt-sensitive essential hypertension. Hypertension 2005, 45, 326–330.

- Johnson, R.J.; Herrera-Acosta, J.; Schreiner, G.F.; Rodriguez-Iturbe, B. Subtle acquired renal injury as a mechanism of salt-sensitive hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 913–923.

- Guzik, T.J.; Hoch, N.E.; Brown, K.A.; McCann, L.A.; Rahman, A.; Dikalov, S.; Goronzy, J.; Weyand, C.; Harrison, D.G. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 2449–2460.

- Barbaro, N.R.; Foss, J.D.; Kryshtal, D.O.; Tsyba, N.; Kumaresan, S.; Xiao, L.; Mernaugh, R.L.; Itani, H.A.; Loperena, R.; Chen, W.; et al. Dendritic cell amiloride-sensitive channels mediate sodium-induced inflammation and hypertension. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 1009–1020.

- Van Beusecum, J.P.; Barbaro, N.R.; McDowell, Z.; Aden, L.A.; Xiao, L.; Pandey, A.K.; Itani, H.A.; Himmel, L.E.; Harrison, D.G.; Kirabo, A.; et al. High salt activates CD11c(+) antigen-presenting cells via SGK (Serum Glucocorticoid Kinase) 1 to promote renal inflammation and salt-sensitive hypertension. Hypertension 2019, 74, 555–563.

- Norlander, A.E.; Saleh, M.A.; Pandey, A.K.; Itani, H.A.; Wu, J.; Xiao, L.; Kang, J.; Dale, B.L.; Goleva, S.B.; Laroumanie, F.; et al. A salt-sensing kinase in T lymphocytes, SGK1, drives hypertension and hypertensive end-organ damage. JCI Insight. 2017, 2.

- Itani, H.A.; McMaster, W.G., Jr.; Saleh, M.A.; Nazarewicz, R.R.; Mikolajczyk, T.P.; Kaszuba, A.M.; Konior, A.; Prejbisz, A.; Januszewicz, A.; Norlander, A.E.; et al. Activation of human T cells in hypertension: Studies of Humanized mice and hypertensive humans. Hypertension 2016, 68, 123–132.

- Fehrenbach, D.J.; Abais-Battad, J.M.; Dasinger, J.H.; Lund, H.; Keppel, T.; Zemaj, J.; Cherian-Shaw, M.; Gundry, R.L.; Geurts, A.M.; Dwinell, M.R.; et al. Sexual dimorphic role of CD14 (Cluster of Differentiation 14) in Salt-sensitive hypertension and renal injury. Hypertension 2021, 77, 228–240.

- Alsheikh, A.J.; Dasinger, J.H.; Abais-Battad, J.M.; Fehrenbach, D.J.; Yang, C.; Cowley, A.W., Jr.; Mattson, D.L. CCL2 mediates early renal leukocyte infiltration during salt-sensitive hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2020, 318, F982–F993.

- Fehrenbach, D.J.; Abais-Battad, J.M.; Dasinger, J.H.; Lund, H.; Mattson, D.L. Salt-sensitive increase in macrophages in the kidneys of Dahl SS rats. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2019, 317, F361–F374.

- Abais-Battad, J.M.; Lund, H.; Fehrenbach, D.J.; Dasinger, J.H.; Mattson, D.L. Rag1-null Dahl SS rats reveal that adaptive immune mechanisms exacerbate high protein-induced hypertension and renal injury. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2018, 315, R28–R35.

- De Miguel, C.; Lund, H.; Mattson, D.L. High dietary protein exacerbates hypertension and renal damage in Dahl SS rats by increasing infiltrating immune cells in the kidney. Hypertension 2011, 57, 269–274.

- De Miguel, C.; Das, S.; Lund, H.; Mattson, D.L. T lymphocytes mediate hypertension and kidney damage in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2010, 298, R1136–R1142.

- De Miguel, C.; Guo, C.; Lund, H.; Feng, D.; Mattson, D.L. Infiltrating T lymphocytes in the kidney increase oxidative stress and participate in the development of hypertension and renal disease. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2011, 300, F734–F742.

- Khraibi, A.A.; Norman, R.A., Jr.; Dzielak, D.J. Chronic immunosuppression attenuates hypertension in Okamoto spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1984, 247, H722–H726.

- Norman, R.A., Jr.; Galloway, P.G.; Dzielak, D.J.; Huang, M. Mechanisms of partial renal infarct hypertension. J. Hypertens. 1988, 6, 397–403.

- Mattson, D.L.; James, L.; Berdan, E.A.; Meister, C.J. Immune suppression attenuates hypertension and renal disease in the Dahl salt-sensitive rat. Hypertension 2006, 48, 149–156.

- Mattson, D.L.; Lund, H.; Guo, C.; Rudemiller, N.; Geurts, A.M.; Jacob, H. Genetic mutation of recombination activating gene 1 in Dahl salt-sensitive rats attenuates hypertension and renal damage. Am. J. Physiol. Regul Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2013, 304, R407–R414.

- Rudemiller, N.P.; Lund, H.; Priestley, J.R.; Endres, B.T.; Prokop, J.W.; Jacob, H.J.; Geurts, A.M.; Cohen, E.P.; Mattson, D.L. Mutation of SH2B3 (LNK), a genome-wide association study candidate for hypertension, attenuates Dahl salt-sensitive hypertension via inflammatory modulation. Hypertension 2015, 65, 1111–1117.

- Lu, X.; Rudemiller, N.P.; Privratsky, J.R.; Ren, J.; Wen, Y.; Griffiths, R.; Crowley, S.D. Classical dendritic cells mediate hypertension by promoting renal oxidative stress and fluid retention. Hypertension 2020, 75, 131–138.

- Zhang, J.; Rudemiller, N.P.; Patel, M.B.; Karlovich, N.S.; Wu, M.; McDonough, A.A.; Griffiths, R.; Sparks, M.A.; Jeffs, A.D.; Crowley, S.D.; et al. Interleukin-1 receptor activation potentiates salt reabsorption in angiotensin II-induced hypertension via the NKCC2 Co-transporter in the Nephron. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 360–368.

- Madhur, M.S.; Lob, H.E.; McCann, L.A.; Iwakura, Y.; Blinder, Y.; Guzik, T.J.; Harrison, D.G. Interleukin 17 promotes angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension 2010, 55, 500–507.

- Saleh, M.A.; McMaster, W.G.; Wu, J.; Norlander, A.E.; Funt, S.A.; Thabet, S.R.; Kirabo, A.; Xiao, L.; Chen, W.; Itani, H.A.; et al. Lymphocyte adaptor protein LNK deficiency exacerbates hypertension and end-organ inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 1189–1202.

- Chan, C.T.; Sobey, C.G.; Lieu, M.; Ferens, D.; Kett, M.M.; Diep, H.; Kim, H.A.; Krishnan, S.M.; Lewis, C.V.; Salimova, E.; et al. Obligatory role for B cells in the development of angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Hypertension 2015, 66, 1023–1033.

- Caillon, A.; Paradis, P.; Schiffrin, E.L. Role of immune cells in hypertension. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 1818–1828.

- Wade, B.; Abais-Battad, J.M.; Mattson, D.L. Role of immune cells in salt-sensitive hypertension and renal injury. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2016, 25, 22–27.

- De Miguel, C.; Rudemiller, N.P.; Abais, J.M.; Mattson, D.L. Inflammation and hypertension: New understandings and potential therapeutic targets. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2015, 17, 507.

- Xiao, L.; Harrison, D.G. Inflammation in hypertension. Can. J. Cardiol. 2020, 36, 635–647.

- Bomfim, G.F.; Rodrigues, F.L.; Carneiro, F.S. Are the innate and adaptive immune systems setting hypertension on fire? Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 117, 377–393.

- Mattson, D.L. Immune mechanisms of salt-sensitive hypertension and renal end-organ damage. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 290–300.

- Foulquier, S. Brain perivascular macrophages: Connecting inflammation to autonomic activity in hypertension. Hypertens. Res. 2020, 43, 148–150.

- Ryan, M.J. An update on immune system activation in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Hypertension 2013, 62, 226–230.

- Harrison, D.G.; Marvar, P.J.; Titze, J.M. Vascular inflammatory cells in hypertension. Front Physiol. 2012, 3, 128.

- Mattson, D.L. Infiltrating immune cells in the kidney in salt-sensitive hypertension and renal injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2014, 307, F499–F508.

- Markó, L.; Kvakan, H.; Park, J.K.; Qadri, F.; Spallek, B.; Binger, K.J.; Bowman, E.P.; Kleinewietfeld, M.; Fokuhl, V.; Dechend, R.; et al. Interferon-γ signaling inhibition ameliorates angiotensin II-induced cardiac damage. Hypertension 2012, 60, 1430–1436.

- Ramseyer, V.D.; Garvin, J.L. Tumor necrosis factor-α: Regulation of renal function and blood pressure. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2013, 304, F1231–F1242.

- Lee, D.L.; Sturgis, L.C.; Labazi, H.; Osborne, J.B., Jr.; Fleming, C.; Pollock, J.S.; Manhiani, M.; Imig, J.D.; Brands, M.W. Angiotensin II hypertension is attenuated in interleukin-6 knockout mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006, 290, H935–H940.

- Wu, J.; Thabet, S.R.; Kirabo, A.; Trott, D.W.; Saleh, M.A.; Xiao, L.; Madhur, M.S.; Chen, W.; Harrison, D.G. Inflammation and mechanical stretch promote aortic stiffening in hypertension through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 616–625.

- Satou, R.; Miyata, K.; Gonzalez-Villalobos, R.A.; Ingelfinger, J.R.; Navar, L.G.; Kobori, H. Interferon-γ biphasically regulates angiotensinogen expression via a JAK-STAT pathway and suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) in renal proximal tubular cells. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 1821–1830.

- Costerousse, O.; Allegrini, J.; Lopez, M.; Alhenc-Gelas, F. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme in human circulating mononuclear cells: Genetic polymorphism of expression in T-lymphocytes. Biochem. J. 1993, 290, 33–40.

- Jurewicz, M.; McDermott, D.H.; Sechler, J.M.; Tinckam, K.; Takakura, A.; Carpenter, C.B.; Milford, E.; Abdi, R. Human T and natural killer cells possess a functional renin-angiotensin system: Further mechanisms of angiotensin II-induced inflammation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 18, 1093–1102.

- Okamura, A.; Rakugi, H.; Ohishi, M.; Yanagitani, Y.; Takiuchi, S.; Moriguchi, K.; Fennessy, P.A.; Higaki, J.; Ogihara, T. Upregulation of renin-angiotensin system during differentiation of monocytes to macrophages. J. Hypertens. 1999, 17, 537–545.

- Elisa, T.; Antonio, P.; Giuseppe, P.; Alessandro, B.; Giuseppe, A.; Federico, C.; Marzia, D.; Ruggero, B.; Giacomo, M.; Andrea, O.; et al. Endothelin receptors expressed by immune cells are involved in modulation of inflammation and in fibrosis: Relevance to the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 147616.

- Soldano, S.; Pizzorni, C.; Paolino, S.; Trombetta, A.C.; Montagna, P.; Brizzolara, R.; Ruaro, B.; Sulli, A.; Cutolo, M. Alternatively activated (M2) macrophage phenotype is inducible by endothelin-1 in cultured human macrophages. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166433.

- Bray, M.A.; Gordon, D. Prostaglandin production by macrophages and the effect of anti-inflammatory drugs. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1978, 63, 635–642.

- Lone, A.; Taskén, K. Proinflammatory and immunoregulatory roles of eicosanoids in T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4.

- Cardinale, J.P.; Sriramula, S.; Mariappan, N.; Agarwal, D.; Francis, J. Angiotensin II-induced hypertension is modulated by nuclear factor-κBin the paraventricular nucleus. Hypertension 2012, 59, 113–121.

- Masson, G.S.; Costa, T.S.; Yshii, L.; Fernandes, D.C.; Soares, P.P.; Laurindo, F.R.; Scavone, C.; Michelini, L.C. Time-dependent effects of training on cardiovascular control in spontaneously hypertensive rats: Role for brain oxidative stress and inflammation and baroreflex sensitivity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94927.

- Rodríguez-Iturbe, B.; Franco, M.; Tapia, E.; Quiroz, Y.; Johnson, R.J. Renal inflammation, autoimmunity and salt-sensitive hypertension. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2012, 39, 96–103.

- Kamat, N.V.; Thabet, S.R.; Xiao, L.; Saleh, M.A.; Kirabo, A.; Madhur, M.S.; Delpire, E.; Harrison, D.G.; McDonough, A.A. Renal transporter activation during angiotensin-II hypertension is blunted in interferon-γ-/- and interleukin-17A-/- mice. Hypertension 2015, 65, 569–576.

- Caruso, R.; Warner, N.; Inohara, N.; Nunez, G. NOD1 and NOD2: Signaling, host defense, and inflammatory disease. Immunity 2014, 41, 898–908.

- Xue, Y.; Enosi Tuipulotu, D.; Tan, W.H.; Kay, C.; Man, S.M. Emerging activators and regulators of inflammasomes and pyroptosis. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 1035–1052.

- Schmidt, F.I.; Lu, A.; Chen, J.W.; Ruan, J.; Tang, C.; Wu, H.; Ploegh, H.L. A single domain antibody fragment that recognizes the adaptor ASC defines the role of ASC domains in inflammasome assembly. J. Exp. Med. 2016, 213, 771–790.

- Chan, A.H.; Schroder, K. Inflammasome signaling and regulation of interleukin-1 family cytokines. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217.

- Van Opdenbosch, N.; Gurung, P.; Vande Walle, L.; Fossoul, A.; Kanneganti, T.D.; Lamkanfi, M. Activation of the NLRP1b inflammasome independently of ASC-mediated caspase-1 autoproteolysis and speck formation. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3209.

- Broz, P.; Pelegrin, P.; Shao, F. The gasdermins, a protein family executing cell death and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 143–157.

- Miao, E.A.; Rajan, J.V.; Aderem, A. Caspase-1-induced pyroptotic cell death. Immunol. Rev. 2011, 243, 206–214.

- Ding, J.; Wang, K.; Liu, W.; She, Y.; Sun, Q.; Shi, J.; Sun, H.; Wang, D.C.; Shao, F. Pore-forming activity and structural autoinhibition of the gasdermin family. Nature 2016, 535, 111–116.

- Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Yang, J.; Zhou, B.; Yang, R.; Ramachandran, R.; Abbott, D.W.; Xiao, T.S. Crystal structures of the full-length murine and human gasdermin d reveal mechanisms of autoinhibition, lipid binding, and oligomerization. Immunity 2019, 51, 43–49.

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ruan, J.; Pan, Y.; Magupalli, V.G.; Wu, H.; Lieberman, J. Inflammasome-activated gasdermin D causes pyroptosis by forming membrane pores. Nature 2016, 535, 153–158.

- Ruan, J.; Xia, S.; Liu, X.; Lieberman, J.; Wu, H. Cryo-EM structure of the gasdermin A3 membrane pore. Nature 2018, 557, 62–67.

- Vince, J.E.; Silke, J. The intersection of cell death and inflammasome activation. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 2349–2367.

- Cheng, S.B.; Nakashima, A.; Huber, W.J.; Davis, S.; Banerjee, S.; Huang, Z.; Saito, S.; Sadovsky, Y.; Sharma, S. Pyroptosis is a critical inflammatory pathway in the placenta from early onset preeclampsia and in human trophoblasts exposed to hypoxia and endoplasmic reticulum stressors. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 927.

- Man, S.M.; Karki, R.; Kanneganti, T.D. Molecular mechanisms and functions of pyroptosis, inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes in infectious diseases. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 277, 61–75.

- Dombrowski, Y.; Peric, M.; Koglin, S.; Kammerbauer, C.; Goss, C.; Anz, D.; Simanski, M.; Glaser, R.; Harder, J.; Hornung, V.; et al. Cytosolic DNA triggers inflammasome activation in keratinocytes in psoriatic lesions. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 82ra38.

- Raupach, B.; Peuschel, S.K.; Monack, D.M.; Zychlinsky, A. Caspase-1-mediated activation of interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta) and IL-18 contributes to innate immune defenses against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 4922–4926.

- Monack, D.M.; Raupach, B.; Hromockyj, A.E.; Falkow, S. Salmonella typhimurium invasion induces apoptosis in infected macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 9833–9838.

- Bergsbaken, T.; Fink, S.L.; Cookson, B.T. Pyroptosis: Host cell death and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 99–109.

- Gong, W.; Shi, Y.; Ren, J. Research progresses of molecular mechanism of pyroptosis and its related diseases. Immunobiology 2020, 225, 151884.

- Man, S.M.; Kanneganti, T.D. Converging roles of caspases in inflammasome activation, cell death and innate immunity. Nature Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 7–21.

- Xia, S. Biological mechanisms and therapeutic relevance of the gasdermin family. Mol. Aspects Med. 2020.

- Tartey, S.; Kanneganti, T.D. Inflammasomes in the pathophysiology of autoinflammatory syndromes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020, 107, 379–391.

- de Torre-Minguela, C.; Mesa del Castillo, P.; Pelegrín, P. The NLRP3 and Pyrin Inflammasomes: Implications in the Pathophysiology of Autoinflammatory Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8.

- Jo, E.K.; Kim, J.K.; Shin, D.M.; Sasakawa, C. Molecular mechanisms regulating NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2016, 13, 148–159.

- Martín-Sánchez, F.; Martínez-García, J.J.; Muñoz-García, M.; Martínez-Villanueva, M.; Noguera-Velasco, J.A.; Andreu, D.; Rivas, L.; Pelegrín, P. Lytic cell death induced by melittin bypasses pyroptosis but induces NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β release. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2984.

- Baroja-Mazo, A.; Martin-Sanchez, F.; Gomez, A.I.; Martinez, C.M.; Amores-Iniesta, J.; Compan, V.; Barbera-Cremades, M.; Yague, J.; Ruiz-Ortiz, E.; Anton, J.; et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome is released as a particulate danger signal that amplifies the inflammatory response. Nat. Immunol. 2014, 15, 738–748.

- Compan, V.; Baroja-Mazo, A.; Lopez-Castejon, G.; Gomez, A.I.; Martinez, C.M.; Angosto, D.; Montero, M.T.; Herranz, A.S.; Bazan, E.; Reimers, D.; et al. Cell volume regulation modulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Immunity 2012, 37, 487–500.

- Pelegrin, P. P2X7 receptor and the NLRP3 inflammasome: Partners in crime. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020.

- Weber, A.N.R.; Bittner, Z.A.; Shankar, S.; Liu, X.; Chang, T.H.; Jin, T.; Tapia-Abellan, A. Recent insights into the regulatory networks of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J. Cell Sci. 2020, 133.

- Prochnicki, T.; Mangan, M.S.; Latz, E. Recent insights into the molecular mechanisms of the NLRP3 inflammasome activation. F1000Research 2016, 5.

- Munoz-Planillo, R.; Kuffa, P.; Martinez-Colon, G.; Smith, B.L.; Rajendiran, T.M.; Nunez, G. K(+) efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity 2013, 38, 1142–1153.

- Takeda, K.; Akira, S. TLR signaling pathways. Semin. Immunol. 2004, 16, 3–9.

- Yi, Y.S. Functional crosstalk between non-canonical caspase-11 and canonical NLRP3 inflammasomes during infection-mediated inflammation. Immunology 2020, 159, 142–155.

- Evavold, C.L.; Ruan, J.; Tan, Y.; Xia, S.; Wu, H.; Kagan, J.C. The pore-forming protein gasdermin D regulates interleukin-1 secretion from living macrophages. Immunity 2018, 48, 35–44.

- Ruhl, S.; Shkarina, K.; Demarco, B.; Heilig, R.; Santos, J.C.; Broz, P. ESCRT-dependent membrane repair negatively regulates pyroptosis downstream of GSDMD activation. Science 2018, 362, 956–960.

- Baroja-Mazo, A.; Compan, V.; Martin-Sanchez, F.; Tapia-Abellan, A.; Couillin, I.; Pelegrin, P. Early endosome autoantigen 1 regulates IL-1beta release upon caspase-1 activation independently of gasdermin D membrane permeabilization. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5788.

- Briard, B.; Fontaine, T.; Samir, P.; Place, D.E.; Muszkieta, L.; Malireddi, R.K.S.; Karki, R.; Christgen, S.; Bomme, P.; Vogel, P.; et al. Galactosaminogalactan activates the inflammasome to provide host protection. Nature 2020, 588, 688–692.

- Chen, J.; Chen, Z.J. PtdIns4P on dispersed trans-Golgi network mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 2018, 564, 71–76.

- Magupalli, V.G.; Negro, R.; Tian, Y.; Hauenstein, A.V.; di Caprio, G.; Skillern, W.; Deng, Q.; Orning, P.; Alam, H.B.; Maliga, Z.; et al. HDAC6 mediates an aggresome-like mechanism for NLRP3 and pyrin inflammasome activation. Science 2020, 369.