The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is affecting society’s health, economy, environment and development. COVID-19 has claimed many lives across the globe and severely impacted the livelihood of a considerable section of the world’s population. We are still in the process of finding optimal and effective solutions to control the pandemic and minimise its negative impacts. In the process of developing effective strategies to combat COVID-19, different countries have adapted diverse policies, strategies and activities and yet there are no universal or comprehensive solutions to the problem. In this context, this paper brings out a conceptual model of multistakeholder participation governance as an effective model to fight against COVID-19. Accordingly, the current study conducted a scientific review by examining multi-stakeholder disaster response strategies, particularly in relation to COVID-19. The study then presents a conceptual framework for multistakeholder participation governance as one of the effective models to fight against COVID-19.

- Multistakeholder Participation in Disaster Management

- COVID-19

- Spatial Decision Support System

- Scientific Review

1. Introduction

2. Policy Announcement from Selected Countries for COVID-19

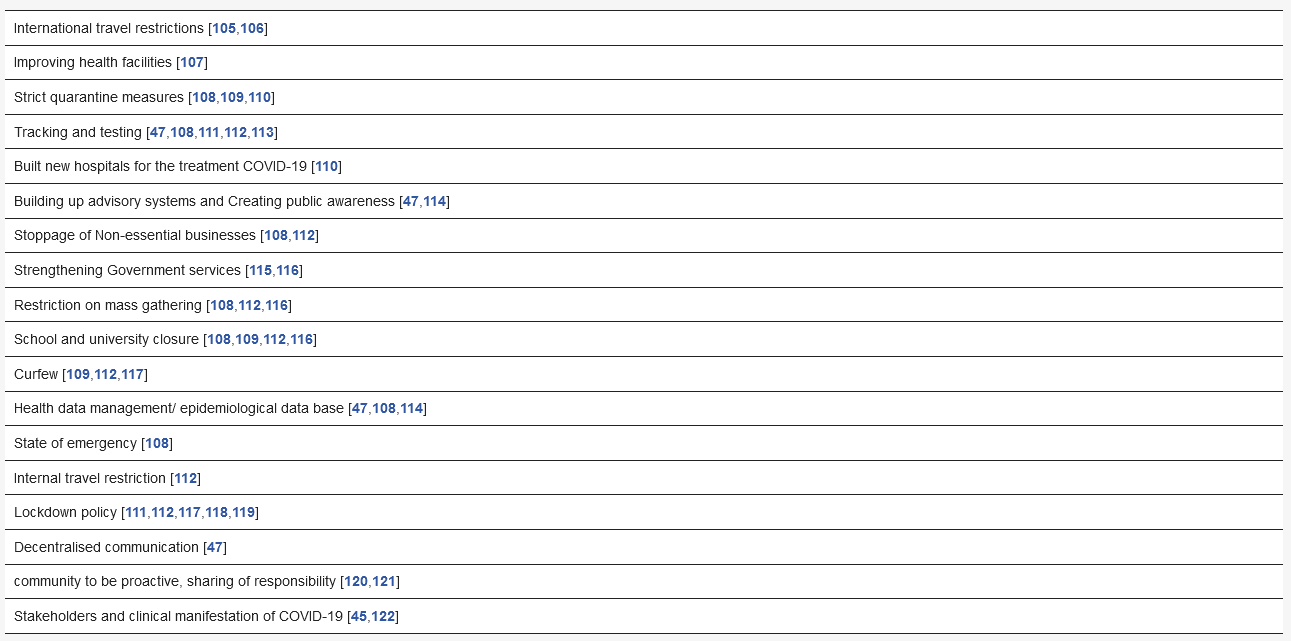

Strategies Followed to Combat COVID-19

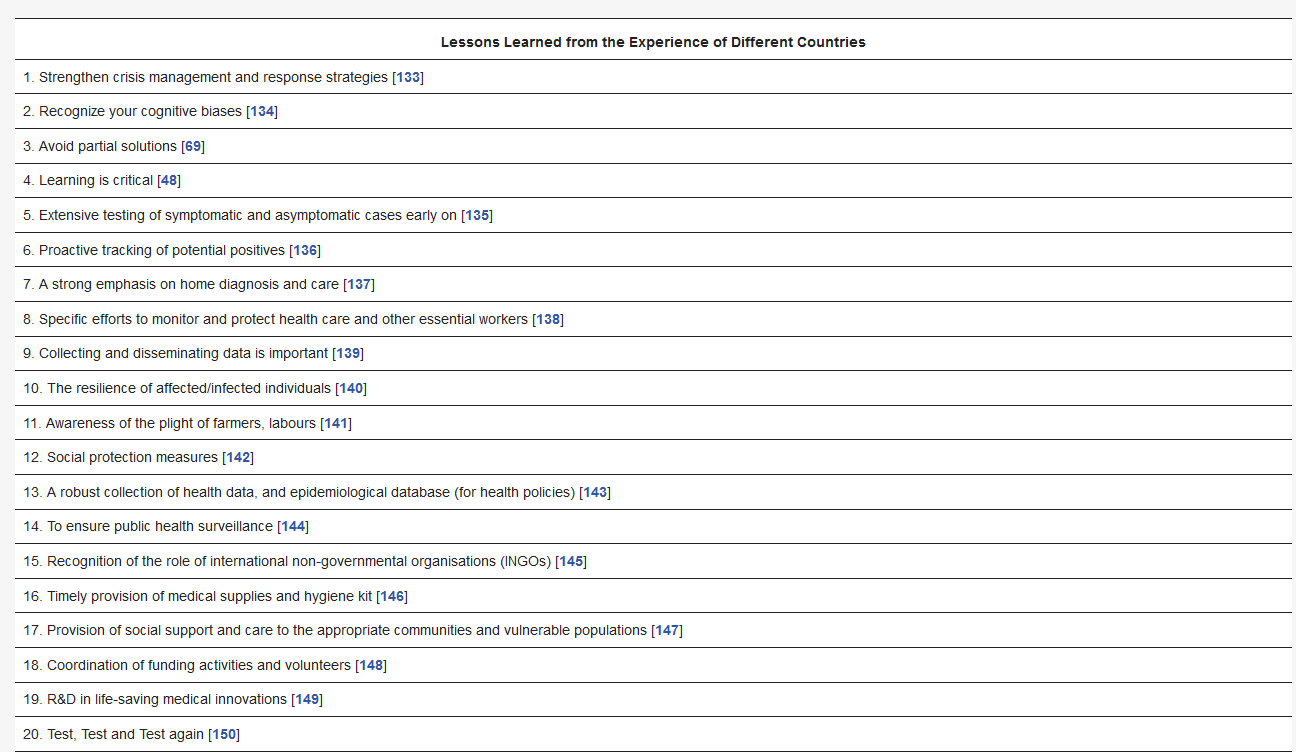

3. Discussion

Importance and Implications of Public Policies

4. Suggestions for Effective Interventions

Scope for Future Research

5. Limitations

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/healthcare9020203

References

- McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. If the world fails to protect the economy, COVID-19 will damage health not just now but also in the future. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 640–642.

- Anyfantaki, S.; Balfoussia, H.; Dimitropoulou, D.; Gibson, H.; Papageorgiou, D.; Petroulakis, F.; Theofilakou, A.; Vasardani, M. COVID-19 and other pandemics: A literature review for economists. Econ. Bull. 2020, 51, 1–36.

- Jordà, Ò.; Singh, S.R.; Taylor, A.M. Longer-Run Economic Consequences of Pandemics; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020.

- Eweje, G.; Sajjad, A.; Nath, S.D.; Kobayashi, K. Multi-stakeholder partnerships: A catalyst to achieve sustainable development goals. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2020.

- Brown, P. Studying COVID-19 in Light of Critical Approaches to Risk and Uncertainty: Research Pathways, Conceptual Tools, and Some Magic from Mary Douglas; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2020.

- Ramkissoon, H. COVID-19 place confinement, pro-social, pro-environmental behaviors, and residents’ wellbeing: A new conceptual framework. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2248.

- Franch-Pardo, I.; Napoletano, B.M.; Rosete-Verges, F.; Billa, L. Spatial analysis and GIS in the study of COVID-19. A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 140033.

- Rice, L. After Covid-19: Urban design as spatial medicine. Urban Des. Int. 2020, in press.

- Zhou, C.; Su, F.; Pei, T.; Zhang, A.; Du, Y.; Luo, B.; Cao, Z.; Wang, J.; Yuan, W.; Zhu, Y.; et al. COVID-19: Challenges to GIS with Big Data. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 77–87.

- Pourghasemi, H.R.; Pouyan, S.; Heidari, B.; Farajzadeh, Z.; Fallah Shamsi, S.R.; Babaei, S.; Khosravi, R.; Etemadi, M.; Ghanbarian, G.; Farhadi, A.; et al. Spatial modeling, risk mapping, change detection, and outbreak trend analysis of coronavirus (COVID-19) in Iran (days between 19 February and 14 June 2020). Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 98, 90–108.

- Wang, C.; Ng, C.; Brook, R. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: Big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. JAMA 2020, 323, 1341–1342.

- Ha, K. A Lesson Learned from the Outbreak of COVID-19 in Korea. Indian J. Microbiol. 2020, 60, 396–397.

- You, J. Lessons from South Korea’s Covid-19 policy response. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 801–808.

- Liu, Y.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, C. The challenges and opportunities of a global health crisis: The management and business implications of COVID-19 from an Asian perspective. Asian Bus. Manag. 2020, 19, 277–297.

- Zodpey, S.; Negandhi, H.; Dua, A.; Vasudevan, A.; Raja, M. Our fight against the rapidly evolving COVID-19 pandemic: A review of India’s actions and proposed way forward. Indian J. Community Med. 2020, 45, 117.

- Shah, A.U.M.; Safri, S.N.A.; Thevadas, R.; Noordin, N.K.; Abd Rahman, A.; Sekawi, Z.; Ideris, A.; Sultan, M.T.H. COVID-19 Outbreak in Malaysia: Actions Taken by the Malaysian Government. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 97, 108–116.

- Capano, G.; Howlett, M.; Jarvis, D.S.; Ramesh, M.; Goyal, N. Mobilizing policy (in) capacity to fight COVID-19: Understanding variations in state responses. Policy Soc. 2020, 39, 285–308.

- Wells, C.R.; Sah, P.; Moghadas, S.M.; Pandey, A.; Shoukat, A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Meyers, L.A.; Singer, B.H.; Galvani, A.P. Impact of international travel and border control measures on the global spread of the novel 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 7504–7509.

- Now, India bans entry of Indians from EU, Turkey and UK. The Economic Times. 18 March 2020. Available online: (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Zangrillo, A.; Beretta, L.; Silvani, P.; Colombo, S.; Scandroglio, A.M.; Dell’Acqua, A.; Fominskiy, E.; Landoni, G.; Monti, G.; Azzolini, M.L. Fast reshaping of intensive care unit facilities in a large metropolitan hospital in Milan, Italy: Facing the COVID-19 pandemic emergency. Crit. Care Resusc. 2020, 22, 91.

- Lu, N.; Cheng, K.-W.; Qamar, N.; Huang, K.-C.; Johnson, J.A. Weathering COVID-19 storm: Successful control measures of five Asian countries. Am. J. Infect. Control 2020, 48, 851–852.

- Åslund, A. Responses to the COVID-19 crisis in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2020, 61, 532–545.

- Hopman, J.; Allegranzi, B.; Mehtar, S. Managing COVID-19 in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA 2020, 323, 1549–1550.

- Peto, J.; Alwan, N.A.; Godfrey, K.M.; Burgess, R.A.; Hunter, D.J.; Riboli, E.; Romer, P.; Buchan, I.; Colbourn, T.; Costelloe, C. Universal weekly testing as the UK COVID-19 lockdown exit strategy. Lancet 2020, 395, 1420–1421.

- Kwok, K.O.; Lai, F.; Wei, V.W.I.; Tsoi, M.T.F.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Tang, J. Comparing the impact of various interventions to control the spread of COVID-19 in twelve countries. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 106, 214–216.

- Djalante, R.; Lassa, J.; Setiamarga, D.; Mahfud, C.; Sudjatma, A.; Indrawan, M.; Haryanto, B.; Sinapoy, M.S.; Rafliana, I.; Djalante, S. Review and analysis of current responses to COVID-19 in Indonesia: Period of January to March 2020. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 100091.

- Alanezi, F.; Aljahdali, A.; Alyousef, S.; Alrashed, H.; Alshaikh, W.; Mushcab, H.; Alanzi, T. Implications of Public Understanding of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia for Fostering Effective Communication Through Awareness Framework. Front. Public Health 2020, 8.

- Dzigbede, K.; Gehl, S.B.; Willoughby, K. Disaster resiliency of US local governments: Insights to strengthen local response and recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020.

- Almutairi, A.F.; BaniMustafa, A.A.; Alessa, Y.M.; Almutairi, S.B.; Almaleh, Y. Public trust and compliance with the precautionary measures against COVID-19 employed by authorities in Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 753.

- Sarkar, K.; Khajanchi, S.; Nieto, J.J. Modeling and forecasting the COVID-19 pandemic in India. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 139, 110049.

- Wan, K.-M.; Ho, L.K.-K.; Wong, N.W.; Chiu, A. Fighting COVID-19 in Hong Kong: The effects of community and social mobilization. World Dev. 2020, 134, 105055.

- Hartley, K.; Jarvis, D.S. Policymaking in a low-trust state: Legitimacy, state capacity, and responses to COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Policy Soc. 2020, 39, 403–423.

- Levy, D.L. COVID-19 and Global Governance. J. Manag. Stud. 2020.

- Baxter, D.; Casady, C.B. A Coronavirus (COVID-19) Triage Framework for (Sub) national Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Programs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1–6.

- Policy Responses to COVID19. Available online: (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Katz, J.; Lu, D.; Sanger-Katz, M. USA: Excess death data compared to confirmed COVID-19 fatalities. The New York Times. Available online: (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Leonardo, L.; Xavier, R. The End of Social Confinement and COVID-19 Re-Emergence Risk. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 746–755.

- Tackling Coronavirus (COVID 19) Contributing to a Global Effort. Available online: (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- Tabish, S. COVID-19 Pandemic: The crisis and the longer-term perspectives. J. Cardiol. Curr. Res. 2020, 13, 41–44.

- Sustainable Development Outlook 2020: Achieving SDGs in the Wake of COVID-19: Scenarios for Policymakers. Available online: (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- World Bank Group Launches First Operations for COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Emergency Health Support, Strengthening Developing Country Responses. Available online: (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Haghani, M.; Bliemer, M.C.; Goerlandt, F.; Li, J. The scientific literature on Coronaviruses, COVID-19 and its associated safety-related research dimensions: A scientometric analysis and scoping review. Saf. Sci. 2020, 129, 104806.

- Maor, M. The political calculus of bad governance: Governance choices in response to the first wave of COVID-19 in Israel. In Proceedings of the ECPR General Conference Online, Colchester, UK, 24–28 August 2020; pp. 24–28.

- Khan, S.; Siddique, R.; Ali, A.; Xue, M.; Nabi, G. Novel coronavirus, poor quarantine, and the risk of pandemic. J. Hosp. Infect.2020, 104, 449–450

- Lee, S.; Hwang, C.; Moon, M.J. Policy learning and crisis policy-making: Quadruple-loop learning and COVID-19 responses in South Korea. Policy Soc. 2020, 39, 363–381.

- Pisano, G.P.; Sadun, R.; Zanini, M. Lessons from Italy’s Response to Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/ faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=57971 (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Bouey, J. Strengthening China’s Public Health Response System: From SARS to COVID-19. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 939–940

- Timmermann, C. Epistemic ignorance, poverty and the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Bioeth. Rev. 2020, 12, 519–527. [CrossRef]

- Onder, G.; Rezza, G.; Brusaferro, S. Case-Fatality Rate and Characteristics of Patients Dying in Relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA 2020, 323, 1775–1776. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marahatta, S.B.; Paudel, S.; Aryal, N. COVID-19 Pandemic: What can Nepal do to Curb the Potential Public Health Disaster? J. Karnali Acad. Health Sci. 2020, 3. [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Walker, J. The Promise and Challenge of Home Health Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. Fam. Physician 2020, 102, 8–9. [PubMed]

- Bielicki, J.A.; Duval, X.; Gobat, N.; Goossens, H.; Koopmans, M.; Tacconelli, E.; van der Werf, S. Monitoring approaches for health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, e261–e267. [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, V.; Restrepo, A.M.H.; Preziosi, M.-P.; Swaminathan, S. Data sharing for novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98, 150. [CrossRef]

- Hynes, W.; Trump, B.; Love, P.; Linkov, I. Bouncing forward: A resilience approach to dealing with COVID-19 and future systemic shocks. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2020, 40, 174–184. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paganini, N.A.K.; Buthelezi, N.; Harris, D.; Lemke, S.; Luis, A.; Koppelin, J.; Karriem, A.; Ncube, F.; Nervi Aguirre, E.; Ramba, T.; et al. Growing and Eating Food during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Farmers’ Perspectives on Local Food System Resilience to Shocks in Southern Africa and Indonesia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8556. [CrossRef]

- Gentilini, U.; Almenfi, M.; Orton, I.; Dale, P. Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33635 (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Xu, B.; Gutierrez, B.; Mekaru, S.; Sewalk, K.; Goodwin, L.; Loskill, A.; Cohn, E.L.; Hswen, Y.; Hill, S.C.; Cobo, M.M. Epidemiologi- cal data from the COVID-19 outbreak, real-time case information. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 1–6. [CrossRef].

- Hussein, M.R.; Apu, E.H.; Shahabuddin, S.; Shams, A.B.; Kabir, R. Overview of digital health surveillance system during COVID-19 pandemic: Public health issues and misapprehensions. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.13633.

- Davies, S.E.; Wenham, C. Why the COVID-19 response needs International Relations. Int. Aff. 2020, 96, 1227–1251. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.-Q.; Yang, L.; Zhou, P.-X.; Li, H.-B.; Liu, F.; Zhao, R.-S. Recommendations and guidance for providing pharmaceutical care services during COVID-19 pandemic: A China perspective. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1819–1824. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelyn, C.D.V.; Viljoen, I.M.; Dhai, A.; PEPPER, M.; Naidu, C. Resource allocation during COVID-19: A focus on vulnerable populations. S. Afr. J. Bioeth. Law 2020, 13, 83.

- Miao, Q.; Schwarz, S.; Schwarz, G. Responding to COVID-19: Community volunteerism and coproduction in China. World Dev. 2020, 137, 105128. [CrossRef]

- Palanica, A.; Fossat, Y. COVID-19 has inspired global healthcare innovation. Can. J. Public Health 2020, 111, 645–648. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Kupferschmidt, K. Countries Test Tactics in ‘War’ against COVID-19; American Association for the Advancement of Science: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Baxter, D.; Casady, C.B. Encouraging and Procuring Healthcare Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) Through Unsolicited Proposals during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic; ResearchGate: Berlin, Germany, 2020.

- Meinzen-Dick, R. Collective action and “social distancing” in COVID-19 responses. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 649–650. [CrossRef]

- Hermanto,D.;Akrim,A.Covid-19Pandemic:ASocialWelfarePerspective.Soc.Sci.Humanit.J.2020,4,1915–1924.

- Megahed,N.A.;Ghoneim,E.M.Antivirus-builtenvironment:LessonslearnedfromCovid-19pandemic.Sustain.CitiesSoc.2020,61, 102350.

- Fontanarosa, P.B.; Bauchner, H. COVID-19—looking beyond tomorrow for health care and society. JAMA 2020, 323, 1907–1908.

- Steinwehr, U. Facing COVID-19, World Health Organization in crisis mode. DW News, 18 May 2020.

- Laxminarayan, R.; Reif, J.; Malani, A. Incentives for reporting disease outbreaks. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90290.

- Huttner, B.; Catho, G.; Pano-Pardo, J.R.; Pulcini, C.; Schouten, J. COVID-19: Don’t neglect antimicrobial stewardship principles! Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 808–810.

- Kost, G.J. Geospatial spread of antimicrobial resistance, bacterial and fungal threats to COVID-19 survival, and point-of-care solutions. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2020.

- Matthiessen, L.; Colli, W.; Delfraissy, J.-F.; Hwang, E.-S.; Mphahlele, J.; Ouellette, M. Coordinating funding in public health emergencies. Lancet 2016, 387, 2197–2198.

- Nygren-Krug, H. The Right(s) Road to Universal Health Coverage. Health Hum Rights 2019, 21, 215–228.

- World Health Organization; OECD; International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Delivering Quality Health Services: A Global Imperative for Universal Health Coverage; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- UN. Universal Health Coverage: Moving Together to Build a Healthier World. Available online: (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Baum, M.; Ognyanova, K.; Lazer, D.; Della Volpe, J.; Perlis, R.H.; Druckman, J.; Santillana, M. The state of the nation: A 50-state covid-19 survey report# 3 vote by mail. OSFPREPRINTS 2020.

- Sherman, W. We Can’t Let Coronavirus Tear Us Apart. Available online: (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- How the Public Sector and Civil Society Can Respond to the Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online: (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Lele, U.; Bansal, S.; Meenakshi, J. Health and Nutrition of India’s Labour Force and COVID-19 Challenges. Econ. Political Weekly 2020, 55, 13.

- Irwin, R.; Smith, R. Rituals of global health: Negotiating the world health assembly. Glob. Public Health 2019, 14, 161–174.

- Wahid, M.A.K.; Nurhaeni, I.D.A.; Suharto, D.G. The Synergy among Stakeholders in Management of Village-Owned Enterprises (BUM Desa); 1st Borobudur International Symposium on Humanities, Economics and Social Sciences (BIS-HESS 2019); Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 317–320.

- Uusikylä, P.; Tommila, P.; Uusikylä, I. Disaster Management as a Complex System: Building Resilience with New Systemic Tools of Analysis. In Society as an Interaction Space; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 161–190.

- Kwan, K.M.W.; Shi, S.Y.; Nabbijohn, A.N.; MacMullin, L.N.; VanderLaan, D.P.; Wong, W.I. Children’s appraisals of gender nonconformity: Developmental pattern and intervention. Child Dev. 2020, 91, e780–e798.

- Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Akhter, S.; Zizi, F.; Jean-Louis, G.; Ramasubramanian, C.; Edward Freeman, R.; Narasimhan, M. Project Stakeholder Management in the Clinical Research Environment: How to Do it Right. Front. Psychiatry 2015, 6, 71.

- Rice, L.; Sara, R. Updating the determinants of health model in the Information Age. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 34, 1241–1249.

- Oliver, N.; Lepri, B.; Sterly, H.; Lambiotte, R.; Deletaille, S.; De Nadai, M.; Letouzé, E.; Salah, A.A.; Benjamins, R.; Cattuto, C.; et al. Mobile phone data for informing public health actions across the COVID-19 pandemic life cycle. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc0764.

- Paul, C.; Pearlman, C.V.; Tulika Singh, L.M.; Stevens, B.K. Multi-stakeholder partnerships: Breaking down barriers to effective cancer-control planning and implementation in low-and middle-income countries. Sci. Dipl. 2016, 5, 1–15.

- Fernandez, A.A.; Shaw, G.P. Academic Leadership in a Time of Crisis: The Coronavirus and COVID-19. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2020, 14, 39–45.