In-home and shared meals have been hypothesized to have positive effects. This narrative review examines research on the influence of in-home eating on diet quality, health outcomes, and family relationships.

- in-home eating

- shared meals

1. Introduction

Evidence suggests that there have been shifts in dietary practices over the past few decades, with less time devoted to food shopping, cooking, and in-home eating despite the potential benefits of in-home food preparation and eating [1]. Paralleling this decrease in time spent preparing food in the home and changes in diet is the worldwide increase in diet-related health concerns such as obesity and diabetes [2][3].

In light of these trends, health experts are seeking effective strategies to combat the obesity epidemic, including the possible role of in-home and family-shared meals. Some research suggests a potential protective effect of home meals on child health, psychosocial outcomes, and family relationships [4]. For example, dining together in the home has been proposed to foster self-esteem, promote academic achievement, and protect against substance abuse in adolescents [5][6][7]. To date, however, there is no available review of current evidence for benefits of in-home meals on diet quality and meal patterns, health outcomes, psychosocial factors, and family relationships.

The purpose of this narrative literature review is to examine the evidence regarding the effects of in-home eating and shared meals. Specifically, the review examines the scientific literature on: (1) factors associated with in-home eating (e.g., lifestyle habits, family demographics); (2) the impact of in-home eating on the nutritional quality of meals; (3) the relationship between in-home eating and child and adolescent health outcomes; and (4) the influence of in-home eating on family relationships.

2. Narrative Literature Review

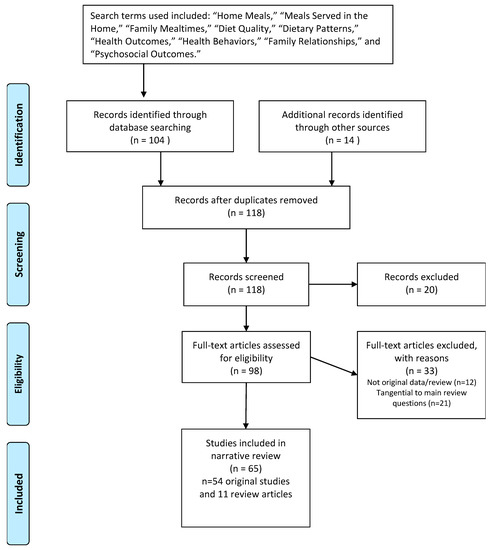

Primary data-based articles and review articles were included in this literature review, which was initially conducted between January and April 2016. Search terms used included: “Home Meals”, “Meals Served in the Home”, “Family Mealtimes”, “Diet Quality”, “Dietary Patterns”, “Health Outcomes”, “Health Behaviors”, “Family Relationships”, and “Psychosocial Outcomes”. A combination search approach was used that included a search of the PubMed database, backward searches of previous published reviews on the topic, and studies the authors were familiar with based on their combined 25 years of research in the area. In the initial literature search, 112 publications were identified and of these, 48 original studies and 11 additional review publications were considered suitable to include in this review. Publications were excluded if they did not report on original data or a systematic review on this topic, or if they were found to be tangential to the main review question. An updated search in May 2018 yielded six additional relevant primary research articles. Analysis of the literature was completed in 2018–2020 (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram.

Studies were organized into categories based on the review questions. Most of the studies were conducted in the U.S., but we have noted non-U.S. study locations in the Results tables where applicable. A preliminary scan revealed the literature is comprised of mostly cross-sectional studies, a variety of methods and measures, and few randomized controlled trials. This limited the ability to apply formal statistical comparisons to the body of literature, so a narrative review approach was chosen, whereby the review team members would each examine studies within outcome categories, summarize their observations, and discuss the findings with the team until consensus was reached. Narrative reviews are preferred when the body of research cannot be summarized quantitatively due to the heterogeneity of research methods and statistical analyses [8][9].

3. Diet Quality and Meal Patterns

We examined the available studies to summarize whether in-home eating and meal sharing are associated with energy intake, fruit and vegetable intake, nutrient intake, dietary patterns, and overall diet quality in children and adolescents. The majority of the studies to date have been cross-sectional (16), and a smaller number are longitudinal (4). In addition, four systematic reviews have been published. Overall findings suggest a positive association between the frequency of family meals and favorable dietary outcomes (Table 1).Table 1. Summary of Diet Quality and Meal Patterns.

| Author(s) and Year | Reference Number | Sample | Main Outcomes | Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diet Quality & Meal Patterns | ||||

| Ayala et al. (2007) | [10] | 167 Mexican American children, 8–18 years old and their mothers | Number of family meals positively associated with fiber intake. | Cross-Sectional |

| Burgess-Champoux et al. (2009) | [11] | 677 adolescents, Project EAT | Five or more family meals per week associated with increased sodium intake for females, but not males. Five or more family meals per week during the first wave of the study was associated with frequency of breakfast, lunch, and dinner meals for males, and only breakfast and dinner for females five year later. |

Longitudinal |

| Burke et al. (2007) | [12] | 594 Irish children, 5–12 years | Reported fiber and micronutrient intake were higher during eating occasions inside the home compared to outside of the home. | Cross-Sectional |

| Chu et al. (2014) | [13] | 3398 Canadian children, 10–11 years | Higher frequency of involvement in home meal preparation was associated with higher diet quality index scores. Children who were involved in meal preparation daily ate 1 more serving/day of vegetables and fruit compared with children who never helped. |

Cross-Sectional |

| Fink et al. (2014) | [14] | 1992 children (age 0 to 19 years) | Five or more family meals per week associated with less sugar-sweetened beverage intake among younger and older children, greater vegetable intake among older children and adolescents, and greater fruit intake among adolescents. | Cross-Sectional |

| Fitzpatrick et al. (2007) | [15] | 1336 parents of children aged 1–4 participating in WIC | Number of days per week the family ate dinner together was positively associated with serving fruit and serving vegetables. | Cross-Sectional |

| Flores et al. (2005) | [16] | 2608 parents of children ages 4–35 months | Minority children less likely than whites to have consistent mealtimes, and more likely to never eat lunch or dinner with their families. The analyses also addressed home safety practices for young children, and found disparities with fewer practices in minority homes. |

Cross-sectional |

| Fulkerson et al. (2009) | [17] | Racially diverse sample of 145 adolescents who attended alternative high school | Family dinner frequency was positively associated with breakfast consumption and fruit intake. | Cross-Sectional |

| Fulkerson et al. (2014) | [18] | Child, adolescent, or adult samples with findings related to family meals or commensal eating | Studies included in review found associations between family meal frequency and intake of fruits and vegetables, micronutrients, and breakfast, and decreased intake of soda, higher-fat foods, unhealthy snacks and cakes, fried foods, and fast food. | Systematic Review |

| Gillman et al. (2000) | [19] | 16,202 youth aged 9–14 | Eating family dinner was associated with consuming more fruits and vegetables, less fried food and soda, less saturated and trans-fat, lower glycemic load, more fiber and micronutrients from food, and no material differences in red meat or snack foods. | Cross-Sectional |

| Haapalahti et al. (2003) | [20] | 404 Finnish children aged 10–11 | Children who ate family dinner regularly consumed less fast food and sweets but more juice than children who did not have regular family dinners. | Cross-Sectional |

| Hammons and Fiese (2011) | [21] | 182,836 children and adolescents across 17 studies | Children and adolescents who ate meals with family 3 or more times per week had healthier dietary patterns than those who ate fewer than 3 meals with family per week. | Meta-Analysis |

| Larson et al. (2006) | [22] | 1710 young adults aged 18–23, Project EAT | Young adults who reported frequent food preparation reported less frequent fast-food use and were more likely to meet dietary objectives for fat, calcium, fruit, vegetable, and whole-grain consumption. | Cross-Sectional |

| Larson et al. (2007) | [23] | 1710 young adults aged 18–23, Project EAT | Family meal frequency during adolescence predicted higher intakes of fruit, vegetables, dark-green and orange vegetables, and key nutrients and lower intakes of soft drinks during young adulthood. | Longitudinal |

| Martin-Biggers et al. (2014) | [24] | Families (with children) | More frequent family meals are associated with greater consumption of healthy foods in children, adolescents, and adults. Adolescents and children who consume fewer family meals consume more unhealthy food. |

Literature Review |

| Naska et al. (2015) | [25] | 23,162 middle-aged European adults | Those who ate more foods outside of the home consumed more sweet and savoury bakery items, soft drinks, juices and other non-alcoholic beverages than those who ate more at home | Cross-Sectional |

| Neumark-Sztainer et al. (2003) | [26] | 4746 adolescents, Project EAT | Frequency of family meals was positively associated with intake of fruits, vegetables, grains, and calcium-rich foods and negatively associated with soft drink intake. Frequency of family meals was associated with consumption of energy, protein, calcium, iron, folate, fiber, and vitamins A, C, E, and B6. |

Cross-Sectional |

| O’Dwyer et al. (2005) | [27] | 958 Irish adults aged 18–64 | Intakes of fiber, micronutrients, calories, protein, fat and carbohydrates were greater at home than away from home. | Cross-Sectional |

| Patrick and Nicklas (2005) | [28] | Families (with children) | Children who eat meals with their families generally consume more healthy foods and nutrients. Eating out is associated with higher intake of fat and calories than eating at home. | Literature Review |

| Poti and Popkin (2011) | [29] | 29,217 children aged 2–18 (national sample) | Between 1977 and 2006, children had an overall increase in energy intake corresponding with a decrease in frequency of eating at home (compared to outside of the home). | Longitudinal |

| Surjadi et al. (2017) | [30] | 6503 children were followed from kindergarten–eighth grade | Family meals in kindergarten and increase in family meal frequency over time both predicted healthier dietary intake in eighth grade among White and Black adolescents, but not among Hispanic or Asian adolescents. | Longitudinal |

| Sweetman et al. (2011) | [31] | 434 children aged 2–5 | Frequency of family mealtimes was unrelated to vegetable consumption or liking. | Cross-Sectional |

| Utter et al. (2008) | [32] | 3245 adolescents (national sample) | Frequency of family meals was associated with consuming five fruits and vegetables per day, eating breakfast, and bringing lunch from home. | Cross-Sectional |

| Videon and Manning (2003) | [33] | 18,177 adolescents (national sample) | Parental presence at family meals was associated with greater consumption of fruits, vegetables, dairy foods, and breakfast. | Cross-Sectional |

| Woodruff and Hanning (2008) | [34] | Families (with adolescent children) | Family meals were generally associated with improved dietary intake. | Systematic Review |

| Woodruff & Hanning (2009) | [35] | 3223 Canadian middle school students | Frequency of family meals was associated with breakfast consumption and decreased consumption of soft drinks. | Cross-Sectional |

Project EAT, a longitudinal study conducted in the U.S. Midwest, has contributed substantially to the literature regarding the influences of family meals on the dietary outcomes of adolescents [26][11][22][23]. In our review, five empirical research reports drew from the Project EAT dataset and all four systematic reviews included Project EAT findings. It is noteworthy that most studies used intakes of specific food groups, typically fruit and vegetable consumption, as a proxy for diet quality; and only one used a validated measure of overall diet quality (the Diet Quality Index–International) [13]. Additionally, while most of the research was conducted in the U.S., a portion of the literature is based on studies in Europe and other nations outside of the U.S. [27][13][20][12][31][25]. The conclusions mostly apply to the U.S. cultural context and food environment.Family meal frequency is positively associated with fruit and vegetable and dairy intakes and breakfast eating; and negatively associated with fried foods, unhealthy snacks and cakes, and sugar-sweetened beverage intake [18][26][17][23][20][19][21][28][32][33][34][35][36]. The impact of family meals on specific foods may differ by age. In a cross-sectional study of 1992 children (age 0 to 19 years), five or more family meals per week was associated with lower sugar-sweetened beverage intake among both younger and older children, greater vegetable intake among older children and adolescents, and greater fruit intake among adolescents [14]. However, one U.K.-based study found that the frequency of family mealtimes was unrelated to vegetable consumption or liking among children ages 2 to 5 years old [31].Family meal frequency has been shown to be positively associated with increased intakes of calcium, fiber, magnesium, potassium, iron, zinc, folate, thiamin, riboflavin, B12, B6, and vitamins A, C, and E [18][26][15][10][23][12][24][28][34]. The evidence regarding caloric intake is inconsistent. Neumark-Sztainer, Hannan et al. [26] found a positive association between frequency of home meals and energy intake in a study of 4746 adolescents. However, a longitudinal nationally representative sample of 29,217 children in the U.S. found that between 1977 and 2006, there was an overall increase in energy intakes and a corresponding decrease in frequency of eating at home [29].The influence of family meals on dietary outcomes may also differ by sex. Burgess-Champoux, Larson et al. [11] found that regular family meals had a positive association with increased sodium intake for females, but not males. Finally, there may be different outcomes by race/ethnicity. A recent study found a positive association between an increase in family meal frequency over time and fruit and vegetable consumption in the eighth grade among white and black adolescents, but not among Hispanic or Asian adolescents[30].

4. Conclusions

Despite what is increasingly becoming “common wisdom,” the evidence that in-home, shared meals, per se, have direct positive effects on diet quality, health outcomes, psychosocial outcomes, and family relationships is greatly limited by research designs and measurement of the hypothesized independent variable. Measures should include how food is prepared and served in the home, not merely whether children and parents eat together, as well as the quality of meals. There is a need for more longitudinal studies that track changes in mealtime frequency and family dynamics over time to predict changes in diet quality, health outcomes, psychosocial outcomes, and family relationships; while incorporating appropriate controls for other factors that may predict key outcomes as well as meal-sharing. More adequately powered intervention studies and randomized trials are needed. Intervention studies that avoid “ceiling effects” by including mainly those who already share meals frequently are also needed. Further, there is a need to pay more attention to family diversity in terms of race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, household composition, and parenting roles.

The emerging results suggest that shared meals and in-home eating may have protective effects against child and adolescent overweight/obesity. However, much more research, with stronger designs and more rigorous measurement of predictors, is warranted.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph18041577

References

- Ramey, V.A. Time Spent in Home Production in the Twentieth-Century United States: New Estimates from Old Data. J. Econ. Hist. 2009, 69, 1–47.

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; CMullany, E.; Biryukov, S.; Abbafati, C.; FeredeAbera, S.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 766–781.

- James, W.P.T. WHO recognition of the global obesity epidemic. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, S120–S126.

- McCullough, M.B.; Robson, S.M.; Stark, L.J. A Review of the Structural Characteristics of Family Meals with Children in the United States. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 627–640.

- Eisenberg, M.E.; Olson, R.E.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M.; Bearinger, L.H. Correlations Between Family Meals and Psychosocial Well-being Among Adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 792–796.

- Sen, B.P.; Goldfarb, S.; Tarver, W.L. Family structure and risk behaviors: The role of the family meal in assessing likelihood of adolescent risk behaviors. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2014, 7, 53–66.

- Eisenberg, M.E.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; A Fulkerson, J.; Story, M.T. Family Meals and Substance Use: Is There a Long-Term Protective Association? J. Adolesc. Health 2008, 43, 151–156.

- Siddaway, A.P.; Wood, A.M.; Hedges, L.V. How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 747–770.

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. Writing Narrative Literature Reviews. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1997, 1, 311–320.

- Ayala, G.X.; Baquero, B.; Arredondo, E.M.; Campbell, N.; Larios, S.; Elder, J.P. Association Between Family Variables and Mexican American Children’s Dietary Behaviors. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2007, 39, 62–69.

- Burgess-Champoux, T.L.; Larson, N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Hannan, P.J.; Story, M. Are Family Meal Patterns Associated with Overall Diet Quality during the Transition from Early to Middle Adolescence? J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2009, 41, 79–86.

- Burke, S.; McCarthy, S.; O’Neill, J.; Hannon, E.; Kiely, M.; Flynn, A.; Gibney, M. An examination of the influence of eating location on the diets of Irish children. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10, 599–607.

- Chu, Y.L.; Storey, K.E.; Veugelers, P.J. Involvement in Meal Preparation at Home Is Associated with Better Diet Quality Among Canadian Children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2014, 46, 304–308.

- Fink, S.K.; Racine, E.F.; Mueffelmann, R.E.; Dean, M.N.; Herman-Smith, R. Family Meals and Diet Quality Among Children and Adolescents in North Carolina. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2014, 46, 418–422.

- Fitzpatrick, E.; Edmunds, L.S.; Dennison, B.A. Positive Effects of Family Dinner Are Undone by Television Viewing. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 666–671.

- Flores, G.; Tomany-Korman, S.C.; Olson, L. Does disadvantage start at home? Racial and ethnic disparities in health-related early childhood home routines and safety practices. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2005, 159, 158–165.

- Fulkerson, J.A.; Kubik, M.Y.; Story, M.; Lytle, L.; Arcan, C. Are There Nutritional and Other Benefits Associated with Family Meals Among At-Risk Youth? J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 45, 389–395.

- Fulkerson, J.A.; Larson, N.; Horning, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. A Review of Associations Between Family or Shared Meal Frequency and Dietary and Weight Status Outcomes Across the Lifespan. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2014, 46, 2–19.

- Gillman, M.W.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Frazier, A.L.; Rockett, H.R.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Field, A.E.; Berkey, C.S.; Colditz, G.A. Family dinner and diet quality among older children and adolescents. Arch. Fam. Med. 2000, 9, 235–240.

- Haapalahti, M.; Mykkanen, H.; Tikkanen, S.; Kokkonen, J. Meal patterns and food use in 10- to 11-year-old Finnish children. Public Health Nutr. 2003, 6, 365–370.

- Hammons, A.; Fiese, B.H. Is frequency of shared family meals related to the nutritional health of children and adolescents? A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 1565–1574.

- Larson, N.I.; Perry, C.L.; Story, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Food Preparation by Young Adults Is Associated with Better Diet Quality. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 2001–2007.

- Larson, N.I.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Hannan, P.J.; Story, M. Family Meals during Adolescence Are Associated with Higher Diet Quality and Healthful Meal Patterns during Young Adulthood. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 1502–1510.

- Martin-Biggers, J.; Spaccarotella, K.; Berhaupt-Glickstein, A.; Hongu, N.; Worobey, J.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C. Come and Get It! A Discussion of Family Mealtime Literature and Factors Affecting Obesity Risk1–3. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 235–247.

- Naska, A.; Katsoulis, M.; Orfanos, P.; Lachat, C.; Gedrich, K.; Rodrigues, S.S.P.; Freisling, H.; Kolsteren, P.; Engeset, D.; Lopes, C.; et al. Eating out is different from eating at home among individuals who occasionally eat out. A cross-sectional study among middle-aged adults from eleven European countries. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1951–1964.

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Hannan, P.J.; Story, M.; Croll, J.; Perry, C. Family meal patterns: Associations with sociodemographic characteristics and improved dietary intake among adolescents. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2003, 103, 317–322.

- A O’Dwyer, N.; Gibney, M.J.; Burke, S.J.; McCarthy, S.N. The influence of eating location on nutrient intakes in Irish adults: Implications for developing food-based dietary guidelines. Public Health Nutr. 2005, 8, 258–265.

- Patrick, H.; Nicklas, T.A. A Review of Family and Social Determinants of Children’s Eating Patterns and Diet Quality. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2005, 24, 83–92.

- Poti, J.M.; Popkin, B.M. Trends in Energy Intake among US Children by Eating Location and Food Source, 1977–2006. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 1156–1164.

- Surjadi, F.F.; Takeuchi, D.T.; Umoren, J. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Longitudinal Patterns of Family Mealtimes: Link to Adolescent Fruit and Vegetable Consumption. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 244–249.e1.

- Sweetman, C.; McGowan, L.; Croker, H.; Cooke, L. Characteristics of family mealtimes affecting children’s vegetable consumption and liking. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 269–273.

- Utter, J.; Scragg, R.; Schaaf, D.; Ni Mhurchu, C. Relationships between frequency of family meals, BMI and nutritional aspects of the home food environment among New Zealand adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 50.

- Videon, T.M.; Manning, C.K. Influences on adolescent eating patterns: The importance of family meals. J. Adolesc. Health 2003, 32, 365–373.

- Woodruff, S.J.; Hanning, R.M. A Review of Family Meal Influence on Adolescents’ Dietary Intake. Can. J. Diet. Pr. Res. 2008, 69, 14–22.

- Woodruff, S.J.; Hanning, R.M. Associations Between Family Dinner Frequency and Specific Food Behaviors Among Grade Six, Seven, and Eight Students from Ontario and Nova Scotia. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 44, 431–436.

- Welsh, E.M.; French, S.A.; Wall, M. Examining the Relationship Between Family Meal Frequency and Individual Dietary Intake: Does Family Cohesion Play a Role? J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2011, 43, 229–235.