FtsZ is an essential and central protein for cell division in most bacteria. Because of its ability to organize into dynamic polymers at the cell membrane and recruit other protein partners to form a “divisome”, FtsZ is a leading target in the quest for new antibacterial compounds.

- bacterial cell division

- FtsZ association states

- protein interactions

- biomolecular condensates

- macromolecular crowding

- phase separation

- cytomimetic media

- persister states

1. Introduction

Resistance to antibiotics is already a major health threat and predicted to worsen unless new strategies are discovered to combat bacterial infections. Efforts in this direction include the identification of new potential antibiotic targets. The well characterized bacterial cell division machinery has lately attracted considerable attention in the quest for these new targets, as reflected by the growing number of reports on the subject [1]. This high level of interest is spurred by the general conservation of cell division proteins in most bacterial species, clear differences from proteins involved in cytokinesis of animal cells, and emerging detailed understanding of the regulatory and structural mechanisms underlying the cell division process in several model bacterial systems.

Bacterial cell division is orchestrated by the divisome, a dynamic multiprotein complex that coordinates partitioning of daughter chromosomes, localized cell wall synthesis, and membrane invagination in order to achieve robust and reliable separation of daughter cells [2]. Within the divisome, the FtsZ GTPase is considered the central protein of the cytokinesis machinery, as it forms a so-called Z-ring where the other components bind at the division site (Figure 1). Although FtsZ shows high structural similarity with the eukaryotic cytoskeletal protein tubulin, their amino acid sequences are less than 20% identical [3], and there are important differences in their GTP binding sites, polymerization features, and protein partners [4,5]. Among bacteria and archaea that carry it, FtsZ is largely conserved, with 40–50% sequence identity [6]; FtsZ orthologs are also present in plastids of algae and plants [1]. Therefore, this protein is a good target for antimicrobials, both for the low probability of cytotoxicity through tubulin cross-inhibition and for potential broad-spectrum activity.

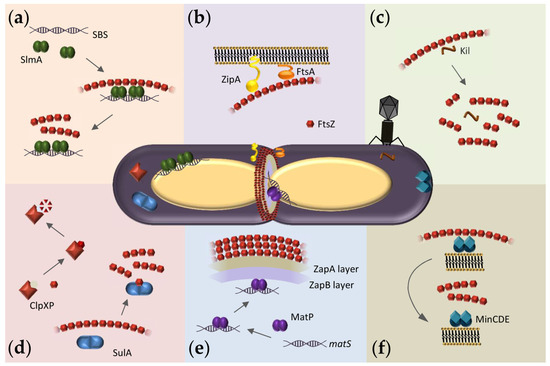

Figure 1. Overview of FtsZ hetero-associations in E. coli as possible targets for antibacterials. At the center, representation of a dividing E. coli cell showing the Z-ring assembled at midcell and FtsZ macromolecular interaction systems. (a) Scheme of the nucleoid occlusion system mediated by SlmA. SlmA bound to specific SBS sequences within the bacterial chromosome, except in the Ter macrodomain, inhibits FtsZ polymerization, thus protecting the chromosome from aberrant scission. (b) The Z-ring is attached to the inner membrane through the protein anchors ZipA and FtsA. (c) Interaction of FtsZ with the bacteriophage λ Kil peptide disrupts FtsZ polymers, resulting in shorter oligomers of variable size. (d) SulA protein, induced by the SOS response, transiently inhibits cell division during DNA repair by sequestering FtsZ monomers. ClpXP protease degrades FtsZ, modulating polymer dynamics and Z-ring formation. (e) Scheme of the Ter- linkage that contributes to Z-ring positioning at midcell. From the membrane inwards, FtsZ interacts with ZapA, ZapB, and MatP. MatP is bound to matS sequences located in the chromosomal Ter macrodomain. (f) The pole-to-pole oscillatory waves of the MinCDE system on the cytoplasmic membrane prevent FtsZ polymerization at the cell poles.

FtsZ function relies on its ability to assemble into GTP-dependent polymers and to interact with other divisome proteins. The FtsZ monomer comprises a highly conserved N-terminal globular domain that contains the GTP binding site, an unstructured and variable linker, and a C-terminal domain that includes a short conserved tail [7]. Crucial interactions with other divisome proteins are mediated through the two conserved domains. In Escherichia coli, the conserved C-terminal tail binds to negative spatial regulators of FtsZ assembly such as MinC [8,9,10] and SlmA [11,12,13] (Figure 1a,f) as well as the two FtsZ membrane anchors FtsA [14,15,16] and ZipA [14,17,18,19] (Figure 1b) and also ClpX, one of the components of the protease complex ClpXP that degrades FtsZ [20,21] (Figure 1d). FtsZ also interacts with ZapA [20], a protein highly conserved across bacterial species that, together with ZapB and the DNA binding protein MatP, forms a complex involved in Z-ring positioning called the Ter-linkage [22] (Figure 1e).

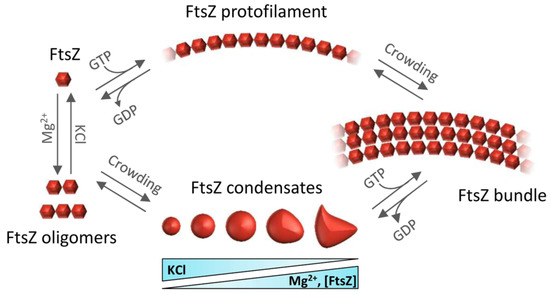

Self-association of FtsZ leads to different types of higher-order structures depending on the conditions (Figure 2). Single-stranded polymers are formed through head-to-tail interactions between globular regions of two subunits [23]. Triggered by GTP binding, polymerization occurs above a critical concentration of protein [24], following a cooperative association mechanism [25]. Active GTPase sites are formed at the contact interface between two monomers [7]. The sizes of the filaments, which remain assembled until GDP accumulates due to GTP hydrolysis, depend on the conditions [26,27,28,29,30] and they laterally associate into bundles in crowded environments [31,32,33]. There is extensive literature available on the polymerization of FtsZ (see, for instance, [25]) and its inhibition, which leads to suppression of cell division and cell death [34].

Figure 2. Overview of the assemblies formed by FtsZ self-association. FtsZ-GDP monomers form oligomers favored by magnesium and low salt. Under crowding conditions, FtsZ-GDP reversibly phase-separates into biomolecular condensates whose number and size depend on FtsZ, KCl, and Mg2+ concentrations. GTP addition triggers FtsZ polymerization whether the protein is in oligomers or in condensates. Macromolecular crowding favors the lateral association of single stranded filaments to form bundles.

When bound to GDP, FtsZ forms non-cooperative isodesmic oligomers whose size is modulated by salt and magnesium [35], and which increase in length in physiological crowding conditions [36]. In vivo, this GDP form of FtsZ is likely transient because of rapid exchange with GTP, except during starvation conditions. The GDP form of FtsZ is active in recognition of other proteins, including the aforementioned ZipA, MinC, and SlmA [37,38,39]. FtsZ-GDP is also a key player in the sequestration mechanisms used by FtsZ polymerization antagonists like the DNA damage-inducible SulA protein or the Kil peptide expressed by infecting bacteriophage λ [40,41] (Figure 1c,d).

In addition to assembling as polymers, it was recently shown that FtsZ-GDP can also form dynamic phase-separated condensates (defined as membraneless assemblies in which biomolecules concentrate) in vitro under conditions that mimic the crowded cell cytoplasm [42]. Formation of these condensates is facilitated by the interactions between FtsZ and its antagonist SlmA, which itself is bound to DNA. FtsZ can also form these condensates on its own (Figure 2), albeit less efficiently [43]. The assembly of biomolecular condensates arising from phase separation is emerging as a new mechanism for the spatial organization of biomolecules to optimize their function [44]. It provides a new framework to explain biological processes, as well as clues to decipher the mechanisms underlying major human diseases such as neurodegeneration, cancer, and infections, which may feature dysregulation of condensate formation [45]. Although biomolecular condensates were initially described only in eukaryotic cells, recent research shows bacterial proteins can also assemble into these dynamic membraneless compartments in vivo [46,47]. For example, proteins involved in essential bacterial processes such as chromosome segregation, DNA compaction and repair, mRNA transcription, or mRNA degradation have been shown to form condensates in vitro and in vivo [47].

How might antibacterial compounds antagonize FtsZ? One mechanism would simply be to hinder FtsZ self-association [1,48,49]. Indeed, most anti-FtsZ compounds based on rational drug design perturb FtsZ polymerization, by blocking key sites for GTP binding or FtsZ subunit contacts [48]. Another mechanism might be to hyperstabilize or promote inappropriate bundling of FtsZ polymers, which would perturb polymer dynamics and “freeze” them in nonfunctional states [48]. In contrast to targeting of FtsZ polymerization, the heterotypic interactions of FtsZ with other proteins and its indirect binding to the membrane have been relatively under-explored as drug targets. Inhibiting these protein-protein interactions may help to reduce the impact of resistance [1,50]. Furthermore, because FtsZ’s binding partners are not as well conserved, inhibition of these interactions would be more species specific [48]. The reported tendency of FtsZ complexes to undergo crowding-induced dynamic condensation may provide an additional opportunity for therapeutic intervention. Interestingly, condensate formation is often observed in cells growing under stress conditions and thus correlates with the emergence of persisters, a sub-population of dormant cells that survive antibiotic treatment [45,51].

Research on the druggability of FtsZ requires suitable methodology to identify drug candidates and to determine their mechanisms of action. Decades of research into how FtsZ functions in cell division have provided numerous approaches to assess its self-association and its direct or indirect interaction with protein partners, nucleic acids, or the membrane that may be adapted for this purpose. Simple assays amenable to high throughput screening are useful for initial identification of lead compounds. Further elucidation of mechanisms, required for a drug to be approved [52,53], would benefit from orthogonal approaches [54] and reconstruction in cell-like systems to evaluate the effects of crowding, compartmentalization, and the membrane surface on these mechanisms [55,56,57,58]. Such assay systems are particularly useful in cases where the targeted protein complexes mainly assemble in crowded conditions only found inside the cell and/or on lipid membranes.

2. Detection and Quantification of Direct FtsZ-Drug Binding in Solution

Identification of novel antimicrobials directed towards FtsZ requires suitable methods to evaluate direct drug-protein interactions (Figure 3, Table 1). Moreover, binding affinity measurements of the identified candidates are a necessary starting point for the determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs). One of the methods that have been employed for this purpose is fluorescence anisotropy. Anisotropy is very sensitive to size changes, such as those that occur when a small fluorescent species binds to a large macromolecule [62,63]. Among the most widely employed techniques for drug screening [64], fluorescence anisotropy can precisely measure high affinity interactions, and several low volume samples can be simultaneously and rapidly analyzed by using a plate reader equipped with polarizers. Anisotropy has been used to determine the binding affinity between a boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY)-labeled oxazole-benzamide inhibitor and FtsZs from a variety of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [65]. In addition, this technique has been used to determine interactions between FtsZ and 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), a DNA intercalating dye that is also a modulator of FtsZ assembly [66], and the guanidinomethyl biaryl compound 13, a broad spectrum bactericidal agent [67]. An anisotropy-based competition assay has been devised to identify compounds targeting the GTP binding site of FtsZ by using the fluorescent analog 2′/3′-O-(N-methylanthraniloyl) (mant)-GTP. This assay has been used to analyze the binding of compounds such as C8-substituted GTP analogs to FtsZ from the archaeon Methanococcus jannaschii, or the interaction of a variety of synthetic inhibitors of bacterial cell division with Bacillus subtilis FtsZ [68,69]. Insight into the mechanism of action of the above mentioned compound 13 has also been obtained through anisotropy measurements of BODIPY-labeled GTPγS, showing competition with the drug for binding to the GTP site of FtsZ [67].

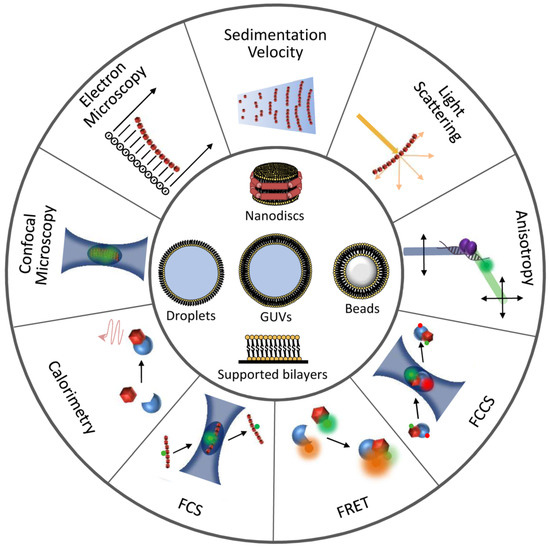

Figure 3. Illustration of techniques and reconstruction approaches useful for the detection and characterization of FtsZ interactions. Experimental approaches to study FtsZ homo- and hetero-association are represented at the outer circumference. Minimal membrane systems and cytomimetic platforms are shown at the center.

Table 1. Biophysical and reconstruction methods useful for the characterization of FtsZ homo-, hetero-associations, and interactions with drugs. Examples marked with an asterisk are mentioned to illustrate the potential use of the technique.

| Method | Fundamentals Refs. |

Information Obtained | Examples Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Techniques in solution | |||

| 90° LS, Sedimentation, EM | [54] | Assessment of polymerization | [4,66,67,69,74,75,76] |

| Fluorescence anisotropy | [62,63] | Quantification of drug binding | [65,66,67,68,69] |

| Assessment of polymerization | [91] * | ||

| Interaction with Kil, ZipA, MinC, SlmA | [41,92], [38,39,93] * | ||

| FCS, FCCS | [63,88] | Assessment of polymerization | [41,90] |

| ITC | [70] | Quantification of drug binding | [71,72] |

| Assessment of polymerization | [83] * | ||

| Interaction with SulA | [40] * | ||

| DLS | [54,78] | Assessment of polymerization | [80,82] |

| SV | [54] | Assessment of polymerization | [41] |

| Interaction with SlmA | [93] * | ||

| FRET, intrinsic fluorescence | [63] | Assessment of polymerization | [30] * |

| Interaction with FtsA, MinC | [94,95] * | ||

| Biosensor | [56] | Interaction with SlmA, MinC | [12,96] * |

| Fluorescence microscopy | [97] | Assessment of polymerization | [98] |

| Interaction with ZapA | [75,99] | ||

| Reconstruction systems | |||

| Nanodiscs | [100] | Interaction with ZipA | [37] * |

| Microbeads | [56] | Interaction with ZipA | [101] * |

| Interaction of FtsA, SlmA with membrane | [102,103] * | ||

| SLBs | [55,57] | Interaction with MinCDE, FtsA, ZipA | [104,105,106,107,108] * |

| Biosensor, plasmonic sensor | [56] | Interaction with ZipA | [109,110] * |

| Interaction of SlmA, MinDE with membrane | [103,111] * | ||

| Microdroplets, liposomes | [55,56,57,58,112] | Interaction with FtsA, ZipA | [113,114,115,116] * |

| Interaction of MinCDE with membrane | [108]* | ||

| Arrangement & distribution of FtsZ species | [116,117,118,119] * | ||

A reference technique for the thermodynamic characterization of binding reactions is isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), based on the measurement of the heat change produced upon interaction [70]. This technique is therefore ideal for detection of inhibitory compounds and selection of candidates showing optimal affinities for their targets. Binding isotherms of the inhibitory MciZ peptide to FtsZs from B. subtilis or Staphylococcus aureus demonstrated that the peptide, produced by the former during sporulation to arrest cytokinesis by disrupting FtsZ polymerization, binds FtsZ from different bacteria by establishing entropically favorable interactions [71]. This method also allowed determination of the binding constants of MciZ mutants with FtsZ. Likewise, ITC was employed to characterize the binding of E. coli FtsZ to cinnamaldehyde, a plant-based small molecule that inhibits FtsZ polymerization and GTPase activity [72].

As for other targets, the identification and characterization of hit compounds acting on FtsZ has benefited from the use of bioinformatics tools and structural approaches like nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) and X-ray crystallography [48]. With these methods, the precise binding sites of the candidates can be ascertained and chemical modifications improving affinity or specificity can be foreseen by docking onto the FtsZ structures available. The use of methods such as NMR and X-ray crystallography to assess direct binding of inhibitors to FtsZ has been thoroughly analyzed elsewhere [4].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/antibiotics10030254