p53 is a 393-amino-acids-long transcription factor composed of a globular DNA binding domain flanked by a transcription activation domain in N-terminal and a tetramerization domain in the C-terminal part of the protein and is active in a homo-tetrameric state.

- p53

1. Introduction

The first mention of a “prion p53” actually dates back to 1995[1]. As a basis to explain the dominant-negative effect of mutant p53 over the wild-type protein, Jo Milner and Elizabeth Medcalf evaluated the in vitro effect of several mutants of p53 (p. R151S, p. R247I, p. R273P, p. R273L) on wild-type p53. They showed that these mutants drive a wild-type p53 bearing a “wild-type” conformation [p53WT] toward a mutant conformation [p53MUT] when co-translated, thereby discriminating two in vitro allosteric variants of wild-type p53[2].

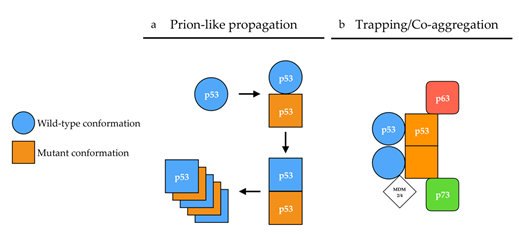

The conformational flexibility of p53 has also provided grounds to the prion p53 hypothesis. Changes in p53 conformation have been monitored by their reactivity to conformation-specific antibodies[3]. For example, pAb1620 antibody recognizes the [p53WT] conformation while pAb240[4] recognizes the [p53MUT] conformation. From there on, p53 mutants were classified as having wild-type [p53WT] or mutant [p53MUT] conformations based on their reactivity with either pAb1620 or pAb240 antibody. Mutants harboring a [p53WT] conformation were, however, not systematically transcriptionally active. These observations later gave rise to the subdivision of p53 mutants into two categories: (i)“DNA contact” mutants (R273H, R248Q, R248W), which have a decreased ability to bind DNA, and (ii) “conformation or structural” mutants (R175H, G245S, R249S, R282H), in which mutations induce a local to global destabilization of the protein structure[1][5] that exposes specific motives at the surface of the protein, thereby allowing reactivity with the pAb240 antibody. However, the relevance of these two classes of mutants is being challenged[6][7]. Some mutations such as p.V135A lead to a [p53WT] conformation when translated at 30 °C, but the protein undergoes a conversion to a [p53MUT] conformation within two minutes when the temperature shifts from 30 °C to 37 °C[8], also illustrating p53 conformational flexibility. Hence, the apparent ability of some p53 mutants to induce a conformational shift of a wild-type p53 protein bearing a [p53WT] conformation towards a [p53MUT] conformation, together with the existence of alternative conformations of p53 gave ground to the “prion p53” hypothesis[1][9], at a time when the prion protein PrPSc was in the limelight (Figure 1a).

Figure 1. Proposed mechanisms of p53 aggregation. (a) According to the prion-like hypothesis, mutant p53 (orange) in a [p53MUT] conformation (square) induces a conformational shift of wild-type p53 (blue) from a [p53WT] (circle) conformation toward a [p53MUT] conformation in a prion-like manner. In a [p53MUT] conformation, wild-type and mutant p53 form amyloid fibers. (b) According to the co-aggregation/trapping hypothesis, mutant p53 hetero-tetramerizes with wild-type p53. The unfolded core of mutant p53 allows new interactions with p63/p73 isoforms and MDM2/4 in a trapping/co-aggregation mechanism.

2. p53 Aggregation in Tissue Samples and Tumor Cell Lines

p53 mutants have early on been described as forming aggregates in tissue samples and tumor cell lines. p53 has indeed been shown to form protein aggregates that abnormally accumulate in the nucleus and sometimes in the cytoplasm of cells from several types of tumor samples[10][11][12][13][14][15]. The aggregative features of p53 have been monitored for a time by immunohistochemistry (anti-p53 antibodies DO-1 and others) as a surrogate for the identification of tumors carrying p53 mutation[11][16][17][18], which is associated with worsened cancer prognosis (reviewed in[19]). However, immunohistochemistry often fails to deliver consistent results and is thus not the expected gold standard[20][17].

The amyloid nature of p53 aggregates has been mostly explored by co-localization experiments relying on anti-p53 antibodies, anti-fibrils antibodies (OC, A11[21][22][23]) or amyloid dyes (thioflavin T, thioflavin S or Congo red). However, major variations are observed in the quantity and features of p53 aggregation, depending on the cell type, the mutation of p53 or the method used to quantify said aggregation[19][24][25][26][27][28], thereby rendering arduous any extensive comparison. In addition, the nature of the proteins forming the A11/OC-positive or amyloid dye-positive protein aggregates was not determined, thus the sometimes-partial co-localization of p53 with these amyloid aggregates precludes, for now, p53 from being classified as a genuine amyloid by the International Society of Amyloidosis nomenclature committee[29][30].

Studies concerning p53 aggregation have been limited to the canonical (full-length FL-p53ɑ) isoform of p53 and its mutant forms. However, recent reports focused on the potential aggregation of p53 isoforms ∆40p53[31] and ∆133p53[32][33] have opened new perspective to the field. The tissue-specific expression of p53 isoforms[34] could indeed partially account for the diversity of p53 aggregation phenotypes observed.

3. p53 Aggregation: In Vitro Dynamics

Despite the fact that only 36 proteins have been shown to form pathogenic amyloids in vivo, it is important to note that in vitro amyloid formation is observed for many more protein sequences. It is actually a property shared by many, if not all, natural polypeptide chains, once placed in the appropriate conditions[35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42], and it seems that p53 is no exception to the rule. Indeed, a large body of literature reports that, when subjected to high pressure, high temperature, zinc absence, low pH or RNA molecules, full-length p53, N-terminal, core or C-terminal fragments of p53, can be led to convert into either amorphous aggregates or ThT positive amyloid fibers in vitro[19][27][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51].

The nucleation-dependent mechanism has three characteristics: the existence of a lag time, critical concentration and seeding. The lag time corresponds to the time required for nucleus formation during which the protein appears to be soluble. In contrast with nucleation-dependent polymerization, the growth of a linear polymer does not require nucleation and is characterized by the sequential buildup of intermediates. No lag time is observed, and supersaturated solutions rapidly aggregate. This process can be difficult to distinguish from a nucleation-dependent process with a very short lag time or from seeded growth[52]. The in vitro kinetics of p53 aggregation indeed differs from that of the classical nucleation-growth formation of amyloid fibrils, as the initiation of p53 aggregation happens to be relatively rapid[19][45][53] and as such is reminiscent of that of a linear polymer. The kinetics of p53 aggregation involves the formation of small aggregates that rapidly form amyloid structures that bind ThT and subsequently grow into larger amorphous aggregates. The progress curves fit to a two-step sequential pattern[54][55][56] in which a destabilized mutant p53 may co-aggregate with wild-type p53 and its paralogs p63 and p73. In this model, a mutant preferentially adopts an unfolded structure and would primarily react with another fast-unfolding mutant protein while only occasionally trapping a slow-unfolding wild-type protein. The mutant population rapidly self-aggregates before much of the wild-type p53 protein is depleted. However, as wild-type p53 is incorporated in hetero-tetramers by mutants, the continual production of mutant p53 in a cancer cell would gradually trap more and more wild-type p53[57], its paralogs p63 and p73[58][55] and MDM2[59]. The trapping dynamics could also involve molecular chaperone HSP70 as it is proposed to stabilize mutant p.R175H and increase its aggregation[60]. This may account for the observations of co-aggregates in cell lines and in tumor tissue samples, and possibly causing a dominant-negative effect by directly impairing DNA binding activity[57][61][62].

4. p53 Aggregation: The Seeding Attempts

As nucleation is rate-limiting at low saturation levels, adding a seed (preformed nucleus) greatly accelerates the polymerization of molecules from solution[36][52][63][64][65][66]. However, in vitro p53 preformed aggregates did not significantly seed the aggregation of bulk proteins and stoichiometric amounts of aggregation-prone mutants induced only small amounts of wild-type p53 to co-aggregate[54][55][56]. p53 seeding experiments are indeed usually based on large amounts of aggregated proteins (10% of the dilution of aggregated proteins)[19]whereas very small amounts of prion or prionoid aggregates (1% to 0.05%) seed aggregation of bulk protein[64][67][68]. In 2013, based on prior demonstration of amyloid aggregation of p53 in vitro, Forget et al. tackled the question of whether or not an in vitro aggregated full-length p53 could be able to propagate its conformation to endogenous wild-type p53 in cells. These p53 aggregates were shown to penetrate cells via a nonspecific macropinocytosis pathway and to induce the co-aggregation of endogenous wild-type p53 in equally amorphous aggregates[69]. However, this report shows a single cell exhibiting p53 aggregates which hardly demonstrates that p53 can induce the aggregation of endogenous p53 proteins. Co-culture experiments were also used by Gosh et al. to demonstrate the cell-to-cell transmission of amyloid aggregates of p53 that were previously induced by the P8 peptide (PILTIITL, corresponding to the residues 250–257 of p53)[27]. The in vitro mechanism of p53 aggregation corresponds more to trapping by cross-reaction and co-aggregation rather than classical seeding and growth (see below;[55]).

5. p53 Aggregation: The Trapping Evidence

A consequence of prion self-propagation is that PrPC protein overexpression leads to an increased propagation of PrPSc prion due to the increased availability of its substrate[70][71]. This is also a feature of prionoids. However, the dominant-negative inhibition of mutants and isoforms of p53 has been shown to be dose-dependent in Soas-2 cells[72] as well as in S. cerevisiæ[58][73], two models lacking endogenous p53. Conversely, the expression of wild-type p53 has been shown to suppress the growth of tumor cell lines bearing dominant negative p53 mutants[74][75] and to overwhelm the inhibition exerted by mutant p53 on its transcription activity in baker’s yeast[58].

Then, in order to challenge the main ability of prions that is self-propagation, wild-type p53 has been co-expressed in yeast with a mutant p53 (p.R175H or p.R248Q) which expression has been placed under the control of a galactose-inducible promoter in a typical prion-propagation assay[76][77]. When co-expressed with mutant p53, wild-type p53 transcriptional functions were inhibited by the dominant-negative mutant p53. However, as soon as mutant p53 expression was shut off, wild-type p53 fully recovered its transcriptional abilities[58]. These results thus show that mutant p53 did not print its [p53MUT] conformation on wild-type p53 in a prion-like manner in S. cerevisiae, although recent data also suggest that when fused to EYFP, p53 overexpression leads, in some rare yeast cells, to the formation of aggregates that are transmitted across generations[78]. Altogether, these data show that the dominant-negative effect of mutant p53 is dose-dependent and can be reduced or even neutralized by increasing the wild-type/mutant p53 ratio.

The fact that increasing wild-type p53 expression level can overwhelm mutant p53 dominant-negative effect also led to p53-based gene therapy trials relying on adenoviruses. They aimed at restoring p53 tumor suppressive function in cancer cells by thwarting mutant p53 with a therapeutic wild-type p53 gene. Advexin and Gendicine[79] appeared as the main therapeutic candidates, having been used in numerous trials (including phase III). Chinese FDA approved the use of Gendicine in 2003 for head and neck tumors and in 2005 for naso-pharyngeal cancers[80]. To date, more than 30,000 patients have received Gendicine in association with chemo- or radiotherapy with promising results and relatively few side effects[81].

Other therapeutic strategies aim at reactivating mutant p53 tumor suppressor functions. Quinuclidines PRIMA-1 and its analog APR-246 (phase I and phase II clinical trials) have demonstrated their ability to inhibit cell proliferation and increase apoptosis in cancer cell lines and other models, although it has been reported that they could display non-p53 related activity[82]. The ReACp53 peptide targets the aggregation ability of mutant p53 and restores a partial function of the mutant protein, thereby inducing tumor shrinking both in vitro and in vivo[83][84]. These strategies, among others[85], seem to lead to mutant p53 refolding, allowing for a functional recovery of the protein.

Both the successful therapeutic approaches set up to target mutant p53 and the unsuccessful attempts of propagating [p53MUT] conformational phenotype strongly indicate that the p53 protein, be it in a wild-type or mutant state, does not behave as a prion nor as a prionoid.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers13020269

References

- Milner, J. Flexibility: The key to p53 function? Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995, 20, 49–51.

- Milner, J.; Medcalf, E. Cotranslation of activated mutant p53 with wild type drives the wild-type p53 protein into the mutant conformation. Cell 1991, 65, 765–774.

- Ory, K.; Legros, Y.; Auguin, C.; Soussi, T. Analysis of the most representative tumour-derived p53 mutants reveals that changes in protein conformation are not correlated with loss of transactivation or inhibition of cell proliferation. EMBO J. 1994, 13, 3496–3504.

- Gamble, J.; Milner, J. Evidence that immunological variants of p53 represent alternative protein conformation. Virology 1988, 162, 452–458.

- Bullock, A.N.; Fersht, A.R. Rescuing the function of mutant p53. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2001, 1, 68–76.

- Joerger, A.C.; Fersht, A.R. Structural biology of the tumor suppressor p53. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008, 77, 557–582.

- Stein, Y.; Aloni-Grinstein, R.; Rotter, V. Mutant p53 oncogenicity: Dominant-negative or gain-of-function. Carcinogenesis 2020.

- Cook, A.; Milner, J. Evidence for allosteric variants of wild-type p53, a tumour suppressor protein. Br. J. Cancer 1990, 61, 548–552.

- Hainaut, P.; Milner, J. Interaction of heat-shock protein 70 with p53 translated in vitro: Evidence for interaction with dimeric p53 and for a role in the regulation of p53 conformation. EMBO J. 1992, 11, 3513–3520.

- Berg, F.M.V.D.; Tigges, A.J.; Schipper, M.E.I.; Hartog-Jager, F.C.A.D.; Kroes, W.G.M.; Walboomers, J.M.M. Expression of the nuclear oncogene p53 in colon tumours. J. Pathol. 1989, 157, 193–199.

- Bartek, J.; Iggo, R.; Gannon, J.; Lane, D.P. Genetic and immunochemical analysis of mutant p53 in human breast cancer cell lines. Oncogene 1990, 5, 893–899.

- Iggo, R.; Bartek, J.; Lane, D.P.; Gatter, K.; Harris, A.; Harris, A.L. Increased expression of mutant forms of p53 oncogene in primary lung cancer. Lancet 1990, 335, 675–679.

- Moll, U.M.; Riou, G.; Levine, A.J. Two distinct mechanisms alter p53 in breast cancer: Mutation and nuclear exclusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 7262–7266.

- Moll, U.M.; Laquaglia, M.; Benard, J.; Riou, G. Wild-type p53 protein undergoes cytoplasmic sequestration in undifferentiated neuroblastomas but not in differentiated tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 4407–4411.

- Porter, P.L.; Gown, A.M.; Kramp, S.G.; Coltrera, M.D. Widespread p53 overexpression in human malignant tumors. An immunohistochemical study using methacarn-fixed, embedded tissue. Am. J. Pathol. 1992, 140, 145–153.

- Alsner, J.; Jensen, V.; Kyndi, M.; Offersen, B.V.; Vu, P.; Børresen-Dale, A.-L.; Overgaard, J. A comparison between p53 accumulation determined by immunohistochemistry and TP53 mutations as prognostic variables in tumours from breast cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2008, 47, 600–607.

- Iggo, R.D.; Rudewicz, J.; Monceau, E.; Sévenet, N.; Bergh, J.; Sjöblom, T.; Bonnefoi, H. Validation of a yeast functional assay for p53 mutations using clonal sequencing. J. Pathol. 2013, 231, 441–448.

- Yue, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, M.; Feng, Z.; Hu, W. Mutant p53 in cancer: Accumulation, gain-of-function, and therapy. J. Mol. Biol. 2017, 429, 1595–1606.

- Ana P. D. Ano Bom; Luciana P. Rangel; Danielly C. F. Costa; Guilherme A. P. de Oliveira; Daniel Sanches; Carolina A. Braga; Lisandra M. Gava; Carlos H. I. Ramos; Ana O. T. Cepeda; Ana C. Stumbo; et al. Mutant p53 Aggregates into Prion-like Amyloid Oligomers and Fibrils. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, 28152-28162, 10.1074/jbc.m112.340638.

- Magali Olivier; Monica Hollstein; Pierre Hainaut; TP53 Mutations in Human Cancers: Origins, Consequences, and Clinical Use. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2009, 2, a001008-a001008, 10.1101/cshperspect.a001008.

- Kayed, R.; Head, E.; Thompson, J.L.; McIntire, T.M.; Milton, S.C.; Cotman, C.W.; Glabe, C.G. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science 2003, 300, 486–489.

- Glabe, C.G. Conformation-dependent antibodies target diseases of protein misfolding. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004, 29, 542–547.

- Liu, P.; Paulson, J.B.; Forster, C.L.; Shapiro, S.L.; Ashe, K.H.; Zahs, K.R. Characterization of a novel mouse model of alzheimer’s disease—amyloid pathology and unique β-amyloid oligomer profile. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126317.

- Levy, C.B.; Stumbo, A.C.; Bom, A.P.A.; Portari, E.A.; Carneiro, Y.; Silva, J.L.; De Moura-Gallo, C.V. Co-localization of mutant p53 and amyloid-like protein aggregates in breast tumors. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2011, 43, 60–64.

- Xu, J.; Reumers, J.; Couceiro, J.R.; De Smet, F.; Gallardo, R.; Rudyak, S.; Cornelis, A.; Rozenski, J.; Zwolinska, A.; Marine, J.-C.; et al. Gain of function of mutant p53 by coaggregation with multiple tumor suppressors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 285–295.

- Lasagna-Reeves, C.A.; Clos, A.L.; Castillo-Carranza, D.; Sengupta, U.; Guerrero-Muñoz, M.; Kelly, B.; Wagner, R.; Kayed, R. Dual role of p53 amyloid formation in cancer; loss of function and gain of toxicity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 430, 963–968.

- Ghosh, S.; Salot, S.; Sengupta, S.; Navalkar, A.; Ghosh, D.; Jacob, R.; Das, S.; Kumar, R.; Jha, N.N.; Sahay, S.; et al. p53 amyloid formation leading to its loss of function: Implications in cancer pathogenesis. Cell Death Differ. 2017, 24, 1784–1798.

- Navalkar, A.; Ghosh, S.; Pandey, S.; Paul, A.; Datta, D.; Maji, S.K. Prion-like p53 amyloids in cancer. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 146–155.

- Merrill D. Benson; Joel N. Buxbaum; David S. Eisenberg; Giampaolo Merlini; Maria J. M. Saraiva; Yoshiki Sekijima; Jean D. Sipe; Per Westermark; Amyloid nomenclature 2018: recommendations by the International Society of Amyloidosis (ISA) nomenclature committee. Amyloid 2018, 25, 215-219, 10.1080/13506129.2018.1549825.

- Jean D. Sipe; Merrill D. Benson; Joel N. Buxbaum; Shu-Ichi Ikeda; Giampaolo Merlini; Maria J. M. Saraiva; Per Westermark; Amyloid fibril proteins and amyloidosis: chemical identification and clinical classification International Society of Amyloidosis 2016 Nomenclature Guidelines. Amyloid 2016, 23, 209-213, 10.1080/13506129.2016.1257986.

- Nataly Melo dos Santos; Guilherme A. P. de Oliveira; Murilo Ramos Rocha; Murilo M. Pedrote; Giulia Diniz Da Silva Ferretti; Luciana Pereira Rangel; José A. Morgado-Diaz; Jerson L. Silva; Etel Rodrigues Pereira Gimba; Loss of the p53 transactivation domain results in high amyloid aggregation of the Δ40p53 isoform in endometrial carcinoma cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2019, 294, 9430-9439, 10.1074/jbc.ra119.007566.

- Vieler, M.; Sanyal, S. p53 isoforms and their implications in cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 288.

- Lei, J.; Qi, R.; Tang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wei, G.; Nussinov, R.; Ma, B. Conformational stability and dynamics of the cancer-associated isoform Δ133p53β are modulated by p53 peptides and p53-specific DNA. FASEB J. 2018, 33, 4225–4235.

- Thineskrishna Anbarasan; Jean-Christophe Bourdon; The Emerging Landscape of p53 Isoforms in Physiology, Cancer and Degenerative Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 6257, 10.3390/ijms20246257.

- Horwich, A.L. Protein aggregation in disease: A role for folding intermediates forming specific multimeric interactions. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 110, 1221–1232.

- Chiti, F.; Webster, P.; Taddei, N.; Clark, A.; Stefani, M.; Ramponi, G.; Dobson, C.M. Designing conditions for in vitro formation of amyloid protofilaments and fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 3590–3594.

- Fändrich, M.; Fletcher, M.A.; Dobson, C.M. Amyloid fibrils from muscle myoglobin. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 410, 165–166.

- Krebs, M.R.; Wilkins, D.K.; Chung, E.W.; Pitkeathly, M.C.; Chamberlain, A.K.; Zurdoa, J.; Robinson, C.V.; Dobson, C.M. Formation and seeding of amyloid fibrils from wild-type hen lysozyme and a peptide fragment from the β-domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 300, 541–549.

- Guijarro, J.I.; Sunde, M.; Jones, J.A.; Campbell, I.D.; Dobson, C.M. Amyloid fibril formation by an SH3 domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 4224–4228.

- Litvinovich, S.V.; A Brew, S.; Aota, S.; Akiyama, S.K.; Haudenschild, C.; Ingham, K.C. Formation of amyloid-like fibrils by self-association of a partially unfolded fibronectin type III module. J. Mol. Biol. 1998, 280, 245–258.

- Clark, A.; Judge, F.; Richards, J.; Stubbs, J.; Suggett, A. Electron microscopy of network structures in thermally-induced globular protein gels. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 2009, 17, 380–392.

- Canet, D.; Sunde, M.; Last, A.M.; Miranker, A.; Spencer, A.; Robinson, C.V.; Dobson, C.M. Mechanistic Studies of the Folding of Human Lysozyme and the Origin of Amyloidogenic Behavior in Its Disease-Related Variants. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 6419–6427.

- DiGiammarino, E.L.; Lee, A.S.; Cadwell, C.; Zhang, W.; Bothner, B.; Ribeiro, R.C.; Zambetti, G.; Kriwacki, R.W. A novel mechanism of tumorigenesis involving pH-dependent destabilization of a mutant p53 tetramer. Nat. Genet. 2001, 9, 12–16.

- Butler, J.S.; Loh, S.N. Structure, Function, and Aggregation of the Zinc-Free Form of the p53 DNA Binding Domain&dagger. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 2396–2403.

- Ishimaru, D.; Andrade, L.R.; Foguel, D.; Silva, J.L.; Teixeira, L.S.P.; Quesado, P.A.; Maiolino, L.M.; Lopez, P.M.; Cordeiro, Y.; Costa, L.T.; et al. Fibrillar aggregates of the tumor suppressor p53 core domain&dagger. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 9022–9027.

- Lee, A.S.; Galea, C.A.; DiGiammarino, E.L.; Jun, B.; Murti, G.; Ribeiro, R.C.; Zambetti, G.; Schultz, C.P.; Kriwacki, R.W. Reversible amyloid formation by the p53 tetramerization domain and a cancer-associated mutant. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 327, 699–709.

- Rigacci, S.; Bucciantini, M.; Relini, A.; Pesce, A.; Gliozzi, A.; Berti, A.; Stefani, M. The (1–63) region of the p53 transactivation domain aggregates in vitro into cytotoxic amyloid assemblies. Biophys. J. 2008, 94, 3635–3646.

- Silva, J.L.; Vieira, T.C.R.G.; Gomes, M.P.B.; Bom, A.P.A.; Lima, L.M.T.R.; Freitas, M.S.; Ishimaru, D.; Cordeiro, Y.; Foguel, D. Ligand binding and hydration in protein misfolding: Insights from studies of prion and p53 tumor suppressor proteins&dagger. Accounts Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 271–279.

- Kovachev, P.S.; Banerjee, D.; Rangel, L.P.; Eriksson, J.; Pedrote, M.M.; Martins-Dinis, M.M.D.C.; Edwards, K.; Cordeiro, Y.; Silva, J.L.; Sanyal, S. Distinct modulatory role of RNA in the aggregation of the tumor suppressor protein p53 core domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 9345–9357.

- Wang, G.; Fersht, A. Multisite aggregation of p53 and implications for drug rescue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E2634–E2643.

- De Oliveira, G.A.P.; Petronilho, E.C.; Pedrote, M.M.; Marques, M.A.; Vieira, T.C.R.G.; Cino, E.A.; Silva, J.L. The status of p53 oligomeric and aggregation states in cancer. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 548.

- Joseph T. Jarrett; Peter T. Lansbury; Seeding “one-dimensional crystallization” of amyloid: A pathogenic mechanism in Alzheimer's disease and scrapie?. Cell 1993, 73, 1055-1058, 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90635-4.

- Guozhen Wang; Alan R. Fersht; Mechanism of initiation of aggregation of p53 revealed by Φ-value analysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 2437-2442, 10.1073/pnas.1500243112.

- Wang, G.; Fersht, A.R. First-order rate-determining aggregation mechanism of p53 and its implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 13590–13595.

- Wang, G.; Fersht, A.R. Propagation of aggregated p53: Cross-reaction and coaggregation vs. seeding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2443–2448.

- Wilcken, R.; Wang, G.; Boeckler, F.M.; Fersht, A.R. Kinetic mechanism of p53 oncogenic mutant aggregation and its inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 13584–13589.

- Chris D. Nicholls; Kevin G. McLure; Michael A. Shields; Patrick W. K. Lee; Biogenesis of p53 Involves Cotranslational Dimerization of Monomers and Posttranslational Dimerization of Dimers. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 12937-12945, 10.1074/jbc.m108815200.

- Olivier Billant; Alice Léon; Solenn Le Guellec; Gaëlle Friocourt; Marc Blondel; Cécile Voisset; Olivier Billant; The dominant-negative interplay between p53, p63 and p73: A family affair. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 69549-69564, 10.18632/oncotarget.11774.

- Maren H Stindt; Patricia A J Muller; Robert L Ludwig; S Kehrloesser; Volker Dotsch; Karen H Vousden; Functional interplay between MDM2, p63/p73 and mutant p53. Oncogene 2014, 34, 4300-4310, 10.1038/onc.2014.359.

- Milena Wiech; Maciej B. Olszewski; Zuzanna Tracz-Gaszewska; Bartosz Wawrzynow; Maciej Zylicz; Alicja Zylicz; Molecular Mechanism of Mutant p53 Stabilization: The Role of HSP70 and MDM2. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e51426, 10.1371/journal.pone.0051426.

- Chène, P. In vitro analysis of the dominant negative effect of p53 mutants. J. Mol. Biol. 1998, 281, 205–209.

- Willis, A.; Jung, E.J.; Wakefield, T.; Chen, X. Mutant p53 exerts a dominant negative effect by preventing wild-type p53 from binding to the promoter of its target genes. Oncogene 2004, 23, 2330–2338.

- Soto, C.; Estrada, L.; Castilla, J. Amyloids, prions and the inherent infectious nature of misfolded protein aggregates. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006, 31, 150–155.

- Colby, D.W.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; Groth, D.; Legname, G.; Riesner, D.; Prusiner, S.B. Prion detection by an amyloid seeding assay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 20914–20919.

- Rochet, J.-C.; Lansbury, P.T. Amyloid fibrillogenesis: Themes and variations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000, 10, 60–68.

- Jucker, M.; Walker, L.C. Self-propagation of pathogenic protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 501, 45–51.

- Nielsen, L.; Khurana, R.; Coats, A.; Frokjaer, S.; Brange, J.; Vyas, S.; Uversky, V.N.; Fink, A.L. Effect of environmental factors on the kinetics of insulin fibril formation: Elucidation of the molecular mechanism. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 6036–6046.

- Woods, L.A.; Platt, G.W.; Hellewell, A.L.; Hewitt, E.W.; Homans, S.W.; Ashcroft, A.E.; Radford, S.E. Ligand binding to distinct states diverts aggregation of an amyloid-forming protein. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 730–739.

- Karolyn J. Forget; Guillaume Tremblay; Xavier Roucou; p53 Aggregates Penetrate Cells and Induce the Co-Aggregation of Intracellular p53. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e69242, 10.1371/journal.pone.0069242.

- Vilotte, J.-L.; Soulier, S.; Essalmani, R.; Stinnakre, M.-G.; Vaiman, D.; Lepourry, L.; Da Silva, J.C.; Besnard, N.; Dawson, M.; Buschmann, A.; et al. Markedly Increased Susceptibility to Natural Sheep Scrapie of Transgenic Mice Expressing Ovine PrP. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 5977–5984.

- Glatzel, M.; Aguzzi, A. PrPC expression in the peripheral nervous system is a determinant of prion neuroinvasion. J. Gen. Virol. 2000, 81, 2813–2821.

- Yi Sun; Zigang Dong; Kazuki Nakamura; Nancy H. Colburn; Dosage‐dependent dominance over wild‐type p53 of a mutant p53 isolated from nasopharyngeal carcinoma 1. The FASEB Journal 1993, 7, 944-950, 10.1096/fasebj.7.10.8344492.

- Olivier Billant; Marc Blondel; Cécile Voisset; Olivier Billant; p53, p63 and p73 in the wonderland of S. cerevisiae. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 57855-57869, 10.18632/oncotarget.18506.

- Finlay, C.A.; Levine, J. The P53 proto-oncogene can act as a suppressor of transformation. Cell 1989, 11.

- Isaacs, W.B.; Carter, B.S.; Ewing, C.M. Wild-type p53 suppresses growth of human prostate cancer cells containing mutant p53 alleles. Cancer Res. 1991, 51, 6.

- Bach, S.; Tribouillard, D.; Talarek, N.; Desban, N.; Gug, F.; Galons, H.; Blondel, M. A yeast-based assay to isolate drugs active against mammalian prions. Methods 2006, 39, 72–77.

- Voisset, C.; Saupe, S.J.; Galons, H.; Blondel, M. Procedure for identification and characterization of drugs efficient against mammalian prion: From a yeast-based antiprion drug screening assay to in vivo mouse models. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 2009, 9, 31–39.

- Sei-Kyoung Park; Sangeun Park; Christine Pentek; Susan W. Liebman; Tumor suppressor protein p53 expressed in yeast can remain diffuse, form a prion, or form unstable liquid-like droplets. iScience 2021, 24, 102000, 10.1016/j.isci.2020.102000.

- K. Devaraja; Current Prospects of Molecular Therapeutics in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma.. Pharmaceutical Medicine 2019, 33, 269-289, 10.1007/s40290-019-00288-x.

- Wold, W.S.M.; Toth, K.; Adenovirus vectors for gene therapy, vaccination and cancer gene therapy. Curr. Gene Ther. 2013, 13, 421–433, 10.2174/156652321366613112509504.

- Wei-Wei Zhang; Longjiang Li; Dinggang Li; Jiliang Liu; Xiuqin Li; Wei Li; Xiaolong Xu; Michael J. Zhang; Lois A. Chandler; Hong Lin; et al. The First Approved Gene Therapy Product for Cancer Ad-p53(Gendicine): 12 Years in the Clinic. Human Gene Therapy 2018, 29, 160-179, 10.1089/hum.2017.218.

- Qiang Zhang; Vladimir J. N. Bykov; Klas G. Wiman; Joanna Zawacka-Pankau; APR-246 reactivates mutant p53 by targeting cysteines 124 and 277. Cell Death & Disease 2018, 9, 1-12, 10.1038/s41419-018-0463-7.

- Soragni, A.; Janzen, D.M.; Pellegrini, M.; Memarzadeh, S.; Eisenberg, D.; Johnson, L.M.; Lindgren, A.G.; Nguyen, A.T.-Q.; Tiourin, E.; Soriaga, A.B.; et al. A designed inhibitor of p53 aggregation rescues p53 tumor suppression in ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 90–103.

- Duffy, M.J.; Synnott, N.C.; Crown, J. Mutant p53 as a target for cancer treatment. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 83, 258–265.

- Stewart N. Loh; Follow the Mutations: Toward Class-Specific, Small-Molecule Reactivation of p53. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 303, 10.3390/biom10020303.